Raphidiophrys

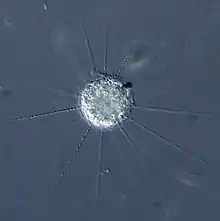

Raphidiophrys is a genus of centrohelid [1] with radiating axopodia.[2] R. intermedia is found in the bottom sludge of freshwater bodies in Canada, Chile, Argentina, Australia, New Zealand, Malaysia, Russia, and central Europe.[3] Raphidiophrys have bipartite scales are a defining characteristic among species. Differences in type and size of scales are used to differentiate amongst the members of this genus. The genus Raphidiophrys was discovered in 1867 by W. Archer. Raphidiophrys is one of very few centrohelids in which dimorphism has been shown.

| Raphidiophrys | |

|---|---|

| |

| Raphidiophrys contractilis | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| (unranked): | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | Acanthocystida |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | Raphidiophrys Archer 1867 |

| Species | |

| |

Habitat and Ecology

Raphidiophrys can be found in freshwater habitats.[4] Species can be found solitarily and/or colonially;[5] in that stage interconnected with cytoplasmic bridges.[6] Species are able to coordinate while in a colony to hunt prey such as Paramecium. Like most heliozoans, Raphidiophrys species can capture prey using their axopodia.[6] In Raphidiophrys contractilis it has been observed that upon capturing prey, its axopodia will contract toward the cell body,[6] however, the presence of Ca2+ is required.[7]

Description of Organism

Raphidiophrys can be distinguished from other heliozoans as being spineless,[5] however this is not true for Raphidiophrys heterophryoidea.[2] Members of this genus are covered in tangential siliceous scales of one or many types including long, narrow scale with sharp points, narrow ellipsoidal and broad oval scales.[5] Bipartite scales with, sometimes-branched, septa are characteristic of Raphidiophrys.[2] Fine structure in scales and size can be used to differentiate amongst species in the genus.[5] Axopodia are numerous [5] and connect to a centroplast found in a spherical body shape.[6] Microtubules extend from the centroplast to form axonemes of the axopodia and are linked together by cross bridges.[6] These axopodia have been observed to contract in Raphidiophrys contractilis.[6] Axopodia may also contain granule kinetocysts [6] that can be used in food uptake [7] and are present in the plasma membrane.[8] The nucleus can be found in the periphery of the cell.[6] Organic spicules have been found on Raphidiophrys heterophryoidea.[2] Raphidiophrys heterophryoidea is the first organism to show a combination of scales and spicules in one species amongst heliozoans demonstrating a transitional state observed at least twice in centrohelid evolution.[2] This is important because of suspicions that like other hacrobians, centrohelids may have haploid and diploid stages that are morphologically different (in centrohelids the ploidy of these morphologically different stages has never been shown).

List of Species

Raphidiophrys capitata Siemensma & Roijacker 1988

Raphidiophrys drakena Zlatogursky 2016

Raphidiophrys elegans Hertwig & Lesser 1874 emend. Penard 1904

Raphidiophrys intermedia Penard 1904

Raphidiophrys heterophryoidea Zlatogursky 2012

Raphidiophrys minuta Nicholls & Dürrschmidt 1985

Raphidiophrys ovalis Siemensma & Roijacker 1988

Raphidiophrys viridis Archer 1867

Raphidiophrys contractilis Kinoshita, Suzaki, Shigenaka & Sugiyama 1995

References

- Okamoto, N.; Chantangsi, C.; Horák, A.; Leander, B.; Keeling, P.; Stajich, J. E. (2009). Stajich, Jason E. (ed.). "Molecular Phylogeny and Description of the Novel Katablepharid Roombia truncata gen. et sp. nov., and Establishment of the Hacrobia Taxon nov". PLoS ONE. 4 (9): e7080. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.7080O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0007080. PMC 2741603. PMID 19759916.

- Zlatogursky, V. V. (2012). Raphidiophrys heterophryoidea sp. nov. (Centrohelida: Raphidiophryidae), the first heliozoan species with a combination of siliceous and organic skeletal elements. European Journal of Protistology, 48(1), 9-16. doi:10.1016/j.ejop.2011.09.004

- Leonov, M. M. (January 2009). "Heliozoan fauna of waterbodies and watercourses of the Central Russian Upland forest-steppe". Inland Water Biology. 2 (1): 6–12. doi:10.1134/S1995082909010027. ISSN 1995-0837.

- Mikrjukov, K. A. (1996). Revision of genera and species composition of lower centroheliozoa. II. family Raphidiophryidae n. tam. Archiv Für Protistenkunde : Protozoen, Algen, Pilze, 147(2), 205-212. doi:10.1016/S0003-9365(96)80035-2

- Dürrschmidt, M., & Nicholls, K. H. (1985). Scale structure and taxonomy of some species of Raphidocystis, Raphidiophrys, and Pompholyxophrys (Heliozoea) including descriptions of six new taxa. Canadian Journal of Zoology, 63(8), 1944-1961. doi:10.1139/z85-288

- KINOSHITA, E., SUZAKI, T., SHIGENAKA, Y., & SUGIYAMA, M. (1995). Ultrastructure and rapid axopodial contraction of a heliozoa, Raphidiophrys contractilis sp. nov. The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 42(3), 283-288. doi:10.1111/j.1550-7408.1995.tb01581.x

- S. M. Mostafa Kamal Khan, Arikawa, M., Omura, G., Suetomo, Y., Kakuta, S., & Suzaki, T. (2003). Axopodial contraction in the heliozoon Raphidiophrys contractilis requires extracellular Ca2. Zoological Science, 20(11), 1367-1372. doi:10.2108/zsj.20.1367

- Sakaguchi, M., Suzaki, T., Mostafa Kamal Khan, S. M., & Hausmann, K. (2002). Food capture by kinetocysts in the heliozoon Raphidiophrys contractilis. European Journal of Protistology, 37(4), 453-458. doi:10.1078/0932-4739-00847