Pueblo pottery

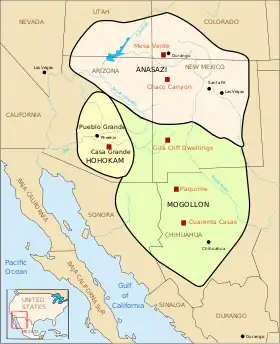

Pueblo pottery are ceramic objects made by the indigenous Pueblo people and their antecedents, the Ancestral Puebloans and Mogollon cultures in the Southwestern United States and Northern Mexico for almost two thousand years.[1] Most Southwestern native peoples developed a pottery tradition, however the Pueblo peoples excelled in form, size, and ornamention. The modern and contemporary Tewa people of Kha'po Owingeh (Santa Clara Pueblo) and P'ohwhóge Owingeh (San Ildefonso Pueblo) favored working in blackware, whereas the Keresan-speaking people of Acoma Pueblo and the Shiwiʼma speaking people of the Pueblo of Zuni work with a wide variety of colors and design motifs.[2][3]

Methods

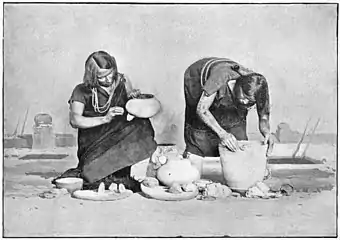

Traditional Pueblo pottery is handmade from locally dug clay that is cleaned by hand of foreign matter. The clay is then worked using coiling techniques to form it into vessels that are primarily used for utilitarian purposes such as pots, storage containers for food and water, bowls and platters. Slab and pinch-pot techniques are used for animal or human figurines. Tempering agents such as sand, old pieces of broken and ground-up pottery or volcanic ash are added to the clay to harden it during firing. Vessels are often decorated with incised patterns, burnished, painted with mineral paints or colored slips that are fixed during the firing process. The vessels are hardened into earthenware in a fire pit dug into the ground. Various locally-sourced materials are used as fuel including wood, dung or coal.[1][4]

.jpg.webp) María and Julián Martinez pit firing blackware pottery (c.1920)

María and Julián Martinez pit firing blackware pottery (c.1920) Sara Fina Tafoya firing blackware pottery at Santa Clara Pueblo, c. 1900

Sara Fina Tafoya firing blackware pottery at Santa Clara Pueblo, c. 1900 Hopi Woman of Oraibi, Third Mesa, making coiled pottery

Hopi Woman of Oraibi, Third Mesa, making coiled pottery Pueblo pottery making

Pueblo pottery making

History

Pottery has been found in the regions occupied by the Ancestral Puebloans; these artifacts have been dated as far back as AD 200.[5] Much of the prehistoric pottery in the area that is now New Mexico was produced by peoples that appear to be related, to some degree, with modern Pueblo people.[6]

Fired pottery is thought to have come to the Southwest by two main vectors: a route along the west coast of Mexico adjacent to the Gulf of California, and entering the area that is now Arizona. The other being an inland route, along the Sierra Madre Occidental range entering into the area now New Mexico. Pottery techniques and technologies moved northward, roughly following the line of what is now the New Mexico-Arizona border; continuing northward into Colorado, Utah and the Grand Canyon area. A third route may have come from Mexico following the Rio Grande north through El Paso and into New Mexico.[1]

The Mimbres branch of the Mogollon culture of Oasisamerica in the region now known as the American Southwest flourished in their mastery of ceramics during AD 1000–1130. Many of their design motifs are still used in contemporary Pueblo pottery.[7] Contemporary Pueblo people believe they are descendents of the Mogollon; anthropologists believe that the Zuni and Hopi people are also potentially related. The oral histories of the Acoma, Hopi and Zuni assert a lineage to the Mimbres and Mogollon.[8]

Prehistoric Puebloan pottery can be grouped into two main categories or traditions: intentionally textured ware for functional, utility purposes such as cooking and storing food; and more durable ware that was well-finished, and often painted for serving food and carrying water.[1][6]

Colonization of the Southwest by Spain had an impact on the lives of the indigenous Pueblo potters, in particular those living in the Rio Grande Valley. They began producing ware for the Catholic Spaniards such as candlesticks, incense censers, and chalices. During the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the Spanish were driven off of pueblo lands by the indigenous people; at this time the two main styles of pottery were those made by the Keres pueblos and by the somewhat more isolated Zuni, both of whom used "watery" mineral glaze techniques with black or brown linear designs. The Tewa potters at this time covered their vessels in cream-colored slip, and painted designs in black glaze, producing pottery with a finer, more precise line quality. After the Spanish reconquered the area in 1692, essentally all of the pueblos stopped producing glazed ware, and instead began producing a matte finished ware using vegetal and mineral paints that were applied prior to firing. For twelve years, (between 1680 and 1692) the indigenous people were free from European influence.[9]

Another shift in sensibilities came with the arrival of the railroad, which was completed in New Mexico in 1880. This brought travelers, anthropologists, archaeologists and tourists to the pueblo lands, and along with these came collecting expeditions, commercialization, and looting of historical pottery.[9]

Pueblo Era I

Pueblo I Era (AD 750–900) pottery followed the Basketmaker Culture pottery making tradition in the Southwest. Simple gray pottery forms with neckbands were the most common types found at Pueblo I sites, although redware and black-on-white forms also developed during the Pueblo I era[1][10] Utility grayware was found throughout the regions occupied by the Mogollon, Hokoma and Ancestral Puebloans (formerly referred to as the Anasazi). Pueblo I Era potters experimented with various materials, most commonly sand or crushed sandstone, to temper their clay for hardness. In the later years of the Pueblo I period and the early Pueblo II period, potters in the Chaco Canyon and Chuska areas in what is now New Mexico began tempering their clay with crushed potsherds. In the mid AD 700s, a type of pottery emerged named "Lino Gray, Fugitive Red Variety", where red iron oxide slip made from hematite was painted on the exterior surfaces after firing, there may or may not have been a second firing to fix the pigment, however it was fugitive and would often flake or wash off.[1]

Pueblo Era II

_Mimbres_pot%252C_circa_1000_AD_(38027586026).jpg.webp)

Pueblo Era II (AD 900–1150) pottery was most commonly of the utilitarian corrugated greyware type, as well as black-on-white ware. In lesser quantities black-on-orange tradeware has been found.[1][10] During this era, people began living in larger communities some of which had architecture that was for shared public use such as plazas.[11] There have been many types of objects found in addition to jars and bowls such as ladles, pitchers, water canteens, effigy pots, and others. Some of this pottery was used for trade.[12] Red Mesa black-on-white ware was produced in abundance over a large range of land, spanning from the Chaco Canyon and Chuska areas to the north, west to the area where the current town of Holbrook, Arizona now exists, and east to the Rio Grand Valley. Red Mesa open ware, such as bowls were painted with a bright white slip on the interiors, and usually painted with fine black zig-zag lines. Jars were slipped and painted on the exteriors. Some archaeologists have proposed that the production range of Red Mesa ware was limited to Chaco Canyon and was distributed to or traded with people in outlying areas where the influence of Chaco-style architecture was also seen.[1]

Pueblo Era III

Pueblo III Era (AD 1150–1350) pottery was primarily of the corrugated plain greyware and black-on-white ware with geometric design elements. Key to this era is the emergence of polychrome ornamented vessels in latter part of the era, with black, red and orange designs on white.[1][13] Use of mineral pigments made of copper, iron and manganese began in about AD 1050–1200 as far north as the San Juan Basin and as far south as Zuni and the Cibola provinces. While most of the St. John's Polychrome was produced in this western range, there was an outlier, perhaps a sole potter, in the area that is now Santo Domingo Pueblo in the Rio Grande Valley. It may be that this outlier obtained pigments from the Zuni.[1]

Pueblo Era IV

During the Pueblo IV Era (AD 1350–1600) a phasing-out of the corrugated type of utility pottery occurred, and highly ornamented polychrome styles and red, yellow and orange ware eventually replaced black-on-white ware as the dominant style. Mineral paints (rather than plant-based paints) and glazes emerged during this period.[1][14] Some vessels were ornamented with Kachina designs and symbols. Rio Grande Glaze Ware was made, as far north as Santa Fe, and as far south as Elephant Butte, and to the east along the Rio Puerco. Glazing was often used during this period; pots were fired at high temperatures prior to being painted with lead-based mineral pigments until the Spanish cut-off indigenous peoples use of lead ore.[15]

Many pots and fragments thereof of Pueblo Era IV pottery has been found at Pottery Mound a former village along the banks of the Rio Puerco that was inhabited from AD 1350 and 1500. Pottery mound polychrome ware was often slipped with a different color on the inside of the vessel than on the exterior.[16] It was then decorated with various mineral paints before firing, in red, black and ochres. Ceramics found at Pottery mound was not only produced there, but imported from as far away as Hopi, Acoma and Zuni lands.[17][18]

Pueblo Era V

During the Pueblo V Era (AD 1600–present) pueblo culture was influenced by Spanish colonialism. A decrease in populations at the pueblos was due in great part to the introduction of European diseases and other effects of colonialism that had an effect on indigenous material culture, in particular during the earlier years of the era. Later, the establishment of reservations by the federal government caused some people to abandon their former homelands and migrate to other pueblos.[1][19] Some archaeologists believe that Pueblo potters began firing their pots using cattle and sheep dung during this period, as the Spanish kept cattle in corrals, producing large quantities of dung in a contained space. Dung firing would also lessen the use of wood for firing; wood that could be used for architectural purposes. This led potters especially at Santa Clara and San Ildefonso pueblos to experiment with dung-smothered reduction-fired blackware techniques that were further refined in the early 20th century. Lead-based glazes disappeared for 150 years during the Spanish colonial period, as the lead-ore resources near Santa Fe were controlled by the Spanish. With the supply disruption of glaze pigments, some Rio Grande area pueblos stopped producing painted ware entirely, while others transitioned to using vegetal paints for ornamentation.[1]

Examples of Pueblo Eras I through V pottery

Pueblo I Era greyware jar Chaco

Pueblo I Era greyware jar Chaco Pueblo II Era Mesa Verde corrugated coiled greyware olla

Pueblo II Era Mesa Verde corrugated coiled greyware olla Pueblo III Era black-on-white Chaco canteen

Pueblo III Era black-on-white Chaco canteen%252C_1350-1400_C.E.%252C_02.257.2562.jpg.webp) Pueblo IV Era polychrome bowl, 1350-1400 C.E., Brooklyn Museum

Pueblo IV Era polychrome bowl, 1350-1400 C.E., Brooklyn Museum Pueblo V Era Maria Martinez black-on-black pot, 1945, DeYoung Museum

Pueblo V Era Maria Martinez black-on-black pot, 1945, DeYoung Museum

Current era

Modern and contemporary pueblo potters tend to work within their family tradition, although some have developed unique styles that break the traditional vessel format to make innovative pots and ceramic sculptures, while remaining cognizant of their ancestry. They cite their grandmothers and great-grandmothers as their early influences.[20] Currently, there are 21 federally recognized pueblos in the Southwest, all of which have a range of distinctive styles of pottery produced in the historical colonial period and today. Nineteen pueblos are in New Mexico,[21] one is in Arizona, and one is in Texas.[22] Many Puebloans are multi-lingual, speaking indigenous languages as well and English and Spanish. They never entirely conceded their customs and way of life. They have held fast onto their cultures, languages and religious beliefs and practices.[23]

Major traditions and styles

Mogollon utility ware

In general, this type of utilitarian pottery was executed in an iron-rich clay that results in a brown fired color. It has been found as far south as Sonora and Chihuahua, Mexico, and north into the areas that are now New Mexico and Arizona. There is minimal decoration on this ware, limited to incised marks produced with reeds that produced tiny circles, and slight incised lines near the necks of the vessels.[1]

Mogollon slip ware

The Mogollon people produced a type of pottery in which common brown ware would be covered with slip produced by mixing finely ground red clay with water into a smooth, thin paste. The slip would be used to cover the entire pot, or the interior or exterior only before firing. The slipped areas could be burnished into a fine polish, however this coating was sometimes fugitive and would flake off during the firing, the potters learned to selectively paint designs on their pots.[1]

Polished blackware

After 600 CE, a type of polished blackware was produced in the area around south-central New Mexico that was made from brownware clay body with highly polished, iridescent black interiors. This type of pottery was continued to be made until approximately 1400 CE. Archaeologists have determined that the blackened interiors were produced by reduction-firing (reducing the oxygen during the firing process) - this transformed the hematite in clay into black magnetite. The same technique was deployed by Tewa potters of the modern era at San Ildefonso Pueblo and Santa Clara Pueblo.[1]

Greyware (also known as Ancestral Puebloan (Anasazi) utility ware)

.jpg.webp)

Greyware or utility ware is the oldest of traditions in the northern regions of what is now the American Southwest. It is a gray, rough-surfaced ware that was used for food storage and cooking. The most common forms that have been found are pots, however bowls, water canteens, smoking pipes, and ladles or scoops have also been unearthed. The potters during this time may have discovered reduction firing, as numerous pots have been found showing they were fired in an oxidizing atmosphere givng the pots a dark grey to black appearance (not caused by cooking soot). Many of these potters tempered the clay by mixing it with sand, or more commonly with ground sandstone to harden it.[1]

Plain grey utility ware

Plain grey ware is sometimes referred to as "undecorated white ware".[24] It is found in the Petrified Forest area of Arizona, the Zuni area and Cebolleta Mesa area of western New Mexico, the Rio Grande areas, and north towards the Colorado Plateau.[25]

Corrugated ware

Corrugated grey pottery for general utility use ranges in color from light to dark grey. Many pots have been found with traces of soot which indicates they were used for cooking on a fire. This type of pottery was made by coiling the clay, then stamping the coils together with a stick or fingernail. At times the corrugations formed a pattern, however they were not scrapped, polished, slipped or ornamented.[26]

Vegetal (plant-based) painted ware

Ancestral puebloans living in western areas such as what is now northern Arizona developed plant-based pigments with which to ornament their pottery.[27] Some potters at Mesa Verde and in the Upper San Juan regions of what is now Colorado also used vegetal pigments in addition to mineral paints.[1] Plants used for these paints include beeweed and tansy mustard.[28]

In the area that is now southeastern Arizona, Roosevelt Red ware was developed, using vegetal-based pigments rather than mineral pigments. It was initially produced by the Kayenta people and their descendants starting in approximately AD 1280. Very large bowls have been found, dated to around AD 1350, which are thought, by archeologists to be used for feasting; as they are completely absent in any burial sites, therefore evidence points to the former purpose. These often had a line painted on the inside of the bowl which may have been a "maximum fill line." Roosevelt red ware was exchanged with other people in the Southwest.[27] It is mainly found in the Roosevelt Basin, San Pedro Valley, Gila Basin, and Verde Valley of eastern Arizona, but because it was traded or exchanged, it can be found as far away in Arizona as Flagstaff, Winslow, Nogales and Gila Bend, as well as in the area around El Paso, Texas and also at Casas Grandes, in Mexico.[29]

Mineral painted ware

The Ancestral Puebloans developed a type of black-on-white ware that was widely produced throughout the Southwest encompassing areas that are now New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona. There were numerous variations of this tradition, including La Plata, White Mound, Lino, Kiatuthlanna, Chaco, Mesa Verde, Red Mesa and other cultures. Design motifs include parallel lines, solid triangles, interlocking scrolls, and serrated or zig-zag designs. Ground hematite was used for black pigment. Reddish-black and maroon pigments were made from ground iron oxide and rocks containing manganese to produce red-on-white ware.[1]

Red ware

A mineral-based slip-glazed Red ware was developed early in the Glaze-Paint tradition involving the application of red slip to the vessel. The slip was made from mineral sources such as iron, copper and manganese. In the case of open vessels such as bowls at times only the inner or outer surface would be slipped. Sometimes the slip was polished or burnished before firing. This type of pottery was widely traded. Often another color would be introduced, to produce black-on-red ware which became highly prized in the middle and upper Rio Grande regions.[1] Showlow Smudged ware bowls have exteriors that are polished red slip and interiors that are smudged polished black. These people also produced a type of corrugated smudged red ware.[25]

Jeddito yellow ware

Jeddito yellow ware is a type of pottery specific to the Hopi Pueblo and its outlying villages in Northern Arizona, although it was traded with the Navajo and the Puebloan people of New Mexico. The reason for its unique yellow color is due to the type of low-iron local clay and of even more importance, that starting in about AD 1300, the Hopi fired their pottery with coal rather than wood or dung. There are large coal deposits at Black Mesa between Hopi and Navajo lands. This method of firing low-iron clay at high temperatures in an oxidizing atmosphere produced a very durable and hard vitrified pottery, almost like porcelain. They clay body was not tempered with additives. The surfaces were polished before firing, but not glazed nor slipped; often the vessels were painted with various mineral pigments to produce a polychrome end product.[30][31] Yellow ware was also produced by the Sinagua culture of Tuzigoot in central Arizona; some Hopi people trace their roots back to the Sinagua, and they may have cultural and linguistic links to the Zuni pueblo people as well.[32]

Polychrome ware

Mineral, vegetal and glazed polychrome ware has been found dating at least as far back as AD 1300.[1] However, Showlow Black-on-red ware has been found in the Show Low, Arizona area, dated to pre-AD 1200. This type of ware was covered with red slip and painted with a slaty black paint.[25] Many of these pots were traded among the Pueblo people in the Rio Grande Valley and beyond.[1]

Glaze-paint ware

Glaze paint was appeared in the area that is now southwestern Colorado as early as the Basketmaker III Era from AD 500 – 750, just prior to the Pueblo I Era. Carlson and others have proposed that potters who lived in the area where Durango, Colorado now exists accidently developed a pigment from a mineral containing lead that produced a blue-black, greenish-black or maroon glaze.[1][33][34] Potters living in the Chaco-Puerco, Mesa Verde and Cibola regions produced non-lead based silica glazes.[1]

Gallery

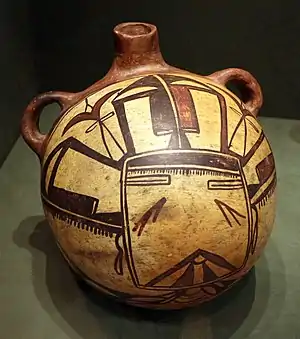

Water pot, Acoma Pueblo, c. 1889–1903, earthenware decorated with slip. De Young Museum

Water pot, Acoma Pueblo, c. 1889–1903, earthenware decorated with slip. De Young Museum Zuni Pueblo Water Jar, 1825-1850

Zuni Pueblo Water Jar, 1825-1850 Large Cochiti Pueblo Pot, c. 1880

Large Cochiti Pueblo Pot, c. 1880 Zia Pueblo olla, showing design influence of Spanish colonialism

Zia Pueblo olla, showing design influence of Spanish colonialism Hopi Payupki Polychrome Jar, 1889, Peabody Museum

Hopi Payupki Polychrome Jar, 1889, Peabody Museum Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi) jar, c. 1100-1250, Honolulu Museum of Art

Ancestral Pueblo (Anasazi) jar, c. 1100-1250, Honolulu Museum of Art Acoma Pueblo gourd-shaped water jug c. 1920, Musée du Nouveau Monde

Acoma Pueblo gourd-shaped water jug c. 1920, Musée du Nouveau Monde%252C_New_Mexico%252C_Acoma_Pueblo%252C_c._1890-1910%252C_earthenware_and_pigment_-_De_Young_Museum_-_DSC00300.JPG.webp) Storage jar (olla), Acoma Pueblo, c. 1890-1910, De Young Museum

Storage jar (olla), Acoma Pueblo, c. 1890-1910, De Young Museum%252C_Johnson_Canyon%252C_Colorado%252C_c._1100-1300_AD%252C_ceramic_-_Native_American_collection_-_Peabody_Museum%252C_Harvard_University_-_DSC06067.jpg.webp) Mug with effigy, Anasazi (Ancestral Pueblo), c. 1100-1300 AD, Peabody Museum

Mug with effigy, Anasazi (Ancestral Pueblo), c. 1100-1300 AD, Peabody Museum Tesuque Pueblo water jar, c. 1880–1890

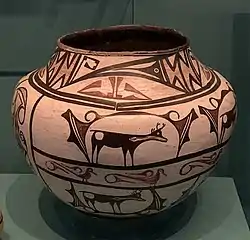

Tesuque Pueblo water jar, c. 1880–1890 Zuni Pueblo olla with "heartline deer" and waterbird motifs, c. 1900

Zuni Pueblo olla with "heartline deer" and waterbird motifs, c. 1900

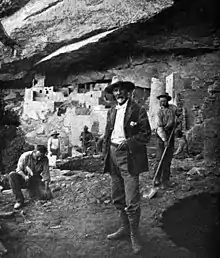

Decontextualization, looting and black market trade

The demand for Ancestral Puebloan pottery as objects of study or collectible aesthetic objects led to most of the significant sites being looted for sale to institutions and private collectors in the Modern era.[35][36] Archaeological excavations, starting in the late 19th century such as the reconnaissance survey of J. Walter Fewkes from the Smithsonian Institution, led to ceramic artifacts being transferred, sometimes in great quantities, to the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC, and its Museum of American Indian Art in New York city, and other institutions. These practices decontextualized these objects from their provenance on tribal lands and among tribal communities to recontextualize them within academic or museum collections. Later, in the 1960s, private individuals began using heavy equipment such as bulldozers and backhoes to excavate for pots and artifacts, which led to a large amount of artifacts being broken or destroyed beyond repair. Many sites were obliterated in the process, including grave sites.[37] Some archaeological publications inspired looters to explore areas described therein, and to steal pots that were then sold on the illicit antiquities market. Severe penalties now exist, including jail time, for looting historical objects from public land and some types of private land.[38][39]

Tourists and recreational pot hunters are also responsible for the looting as are some land owners who loot artifacts on their own property for profit. A Pueblo III Era site on private land, known as Indian Camp Ranch subdivision, in southwest Colorado near Mesa Verde, is sold in lot parcels where wealthy, mostly white buyers can build a home and also excavate their property for artifacts. This type of looting and destruction of the historical record is a loss for the scientific community as well as a "spiritual loss" for the descendents of the Ancestral Puebloans.[38][39]

Despite their rigorous scientific work, some of the anthropologists and ethnographers who studied the Zuni such as Frank Hamilton Cushing, James Stevenson, and Matilda Coxe Stevenson, directly and indirectly participated in cultural appropriation and looting.[40] Cushing "went native" for a number of years, appropriating the Zuni traditional dress and customs; he is credited as the first American participant observer anthropologist. Stevenson, a self-taught anthropologist and his ethnographer wife Matilda (Tilly) met up with Cushing at Zuni, and later embarked on expeditions at Zia, San Ildefonso, Cochiti, Jemez, Santa Clara, San Juan, Nambe, Taos and Picarus pueblos. Tilly wrote extensively on the Zuni, and while she was a role model for women in the sciences, especially anthropology, she arranged for thousands of objects to be mysteriously transferred to the East Coast. Between the three of them, 23,000 Puebloan pottery objects were separated (plundered) from their tribes between 1879 and 1884.[41]

In a 2005 sting operation 100 federal agents stormed eight homes in Blanding, Utah, to arrest 32 non-Native people and recover thousands of artifacts mostly looted from the Four Corners region. Of the 32 brought in, 24 were charged with violating federal laws including the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act and the Archaeological Resources Protection Act, however no one charged was imprisoned. In additon to Mogollon, Hohokam and Anasazi pottery, projectile points, and matates, some as old as BCE 6,000, were recovered. Some of the artifacts were stolen from inside cliff dwellings and were in remarkably good condition. The artifacts are being repatriated by the Bureau of Land Management.[42] Forest Cuch, a Ute tribal member and then-director of the Utah Division of Indian Affairs has said that looting "is a dehumanization of native culture by ignorant people. It's essentially very selfish and greedy.""[43]

The native New Mexican Norman Nelson, who is a second-generation archaeologist estimates that 95% of sites have been looted, and that prehistoric Mimbres black-on-white style pottery fetches high prices on the market, particularly to collectors in "Scandinavia, Sweden, Germany, Japan and China." He estimated, in 2009, that the black-market trade in Native American artifacts was between $5-billion to $6-billion per year illicit industry. He states that many collectors "don't mind crossing the line" into black-market traded objects.[44] The archaeologist, Phil Young, who is also a retired special agent for the National Park Service recalls the 1990s when a series of prominant galleries in Santa Fe that were selling illegally obtained objects.[44]

Modern and contemporary Pueblo potters

Modern period

Native American pottery has long been considered a "traditional" art form, yet it is the innovations of individual potters that have guided the development in materials, styles, methods and forms. Throughout history "eccentric" pieces have been noted that do not fall into established typologies. These were thought to be malformed or odd-ball exceptions to the cultural norms.[45] Harold Gladwin wrote about these outliers: "Such transitional or borderline specimens are thrown into prominance as tangible evidence of continuity in the development of pottery. Without them, the evolutionary story of the ceramics...would be far less convincing."[46] In several museum collections across the country there are a distinctive group of ceramic objects that came from Laguna Pueblo in west central New Mexico,[45] all of them were produced between 1890 and 1920, and they seem to have been made by the same artist. What makes this group interesting is that the materials and techniques are Laguna, however the forms are both Acoma and Laguna, and most surprisingly, the ornamental designs are distinctly Zuni.[45] The American anthropologist, Ruth Bunzel and also Kenneth Chapman wrote about the unique work of a notable Laguna potter of the time, Arroh-ah-och, who Chapman described as a "famous Laguna hermaphrodite". Whether or not that was the case what is clear is that two-spirit artists were common in pueblo cultures and among potters and weavers in particular. Laguna elders spoke of Arroh-ah-och as a "superb potter".[47] Others have suggested that they were originally from Zuni, but later settled at Laguna. What is extraordinary is their experimentation and innovation and their contribution to inter-pueblo aesthetic influences in the pottery of the Southwest in the beginning of the Modern Era.[45]

The modern period of Pueblo pottery began in about 1900, after a stale period in the 1800s, caused by loss of indigenous land to non-indigenous settlers, and the trend within government-run boarding schools to condition Native peoples to be more like whites and to abandon their traditional ways, language and cultures.[23][48] Archeologists plundering their wares for museums and private collections may also have been a factor.[36]

Early 20th century potters from six Tewa speaking pueblos in Northern New Mexico: Kha'po Owingeh (Santa Clara), P'ohwhóge Owingeh (San Ildefonso), Ohkey Owingeh (San Juan), P'osuwaege Owingeh (Pojoaque), Nambe Owingeh (Nambé) and Tetsuge Owingeh (Tesuque), along with a seventh group at Hopi Hano in Arizona developed design innovations using traditional fabrication techniques that initiated modern and contemporary approaches to the Indigenous ceramic arts.[49] The need for income in the modern world along with the rise in tourism by train and later automobile may have been factors in the early 20th century Pueblo pottery revival. While tourism disrupted some cultural traditions it also enabled the Pueblo people to sell their pottery and other craftware such as jewelry, kachina dolls and baskets.[48]

The legacies of families of potters that span many generations is a frequent pattern in Pueblo cultures' historical framework. Potters teach their children and extended family members through direct observation and oral teaching.[50] Often certain designs become an artist's signature style, and there is a sense of "family ownership" of these designs. Dillingham has written that "Potters can usually recognize work done by family members and other potters by the form and design of the vessel." For example, the Acoma pueblo-based Lewis family are known for their fileline designs that have roots in Chacoan culture, as well as for their "heartline deer" motifs that have become a Lewis family trademark.[45]

Tewa matriarch potter and innovator María Martinez (1887–1980) and her husband Julían Martinez (1879–1943) of P'ohwhóge Owingeh were talented potters who began going to fairs in the early 20th century which was not something that most Pueblo people did at the time.[48] By 1915, Maria was known as one of the best potters in New Mexico, and by 1920 she began signing her pots; she is believed to be the first Pueblo potter to do so. She was advised by the Anglo director of the Santa Fe Indian School that it would raise their commercial value, although María herself attached no value to the signature because the quality of the pots themselves were most important.[51] Tewa matriarch potter, Margaret Tafoya (1904–2001) of Kha'po Owingeh was well known for her traditionally produced large blackware pots, carved black-on-black ware, and red ware. She often used motifs such as a bear paw or Avanyu water snake.[49]

At Ohkay Owingeh (formerly San Juan Pueblo), in the 1930s the "San Juan Revival" movement emerged among eight women potters, including Regina Albarado de Cata, Reyecita A. Trujillo, Tomasita Montoya, and others. Cata organized the "San Juan Crafts Club" and led field trips to archeological sites, such as the 15th century site Potsuwi'i, on Pajarito Plateau where they studied the incised designs on polychrome redware. Their work incorporated some of the design tendencies, such as a wide bands of red at the top and bottom of the pots with the incised patterns in a central band.[52]

Art from the Keresan-speaking pueblos have their own unique sensibilities. Acoma Pueblo pottery was long appreciated for its bright white slipped, thin-walled vessels and abstract fine line and checker-board geometric ornamentation. During the Modern era, Acoma as well as the neighboring Pueblo of Laguna refined the line quality even more, as well as introducing bird motifs.[48] Lucy M. Lewis is considered the matriarch potter of Acoma who influenced generations of her descendents and their extended families.[50] In the modern period, artists from Zia Pueblo began to transform their traditional bird like swirling motifs into more realistic, and sometimes elaborate bird and floral designs. Images of dancers and Zia sun symbol were also commonly used. Artists from Santo Domingo pueblo (between Albuquerque to the south and Santa Fe to the north) also use floral and bird motifs along with geometric lines and patterns, usually in red. Zuni artists in the far west-central New Mexico began ornamenting their pottery in the 20th century with dragonflies, deer, owls and frogs, and floral patterns inspired by the Spanish influence.[48]

In Northern New Mexico, artists from San Juan Pueblo deeply carve their pottery into graceful forms; and are known for their red-on-tan work. Modern and contemporary artists of Santa Clara pueblo became well known for their deeply incised or carved blackware and black-on-black ware. The matriarch potter, Margaret Tafoya, made work that was widely collected by museums and private individuals as were the work of several generations of her family and extended family. Other artists from Santa Clara are known for their clay figurative sculptures.[48] The artists from Jemez and Cochiti pueblos also make representational and figurative work and storyteller figurines. In the mid-1960s Cochiti artist Helen Cordero storyteller sculptures became collectible objects popular with the public. Cochiti drummer figurines and Cochiti nativity scenes are more often sought after than functional objects such as bowls and ollas.[48]

The Hopi in Arizona, some of whom speak Hopi-Tewa and others Hopi a Uto-Aztecan language, are also known for figurative work; clay kachina and animal effigies. However their best known work are low, squat vessels often produced in yellow-ware, such as those popularized by the early 20th century modern artist, Nampayo of Hano and her descendents.[53] The Hopi design sensibility and is characterized by swirling geometric stylized birds and other motifs that follow the forms of the vessels.[54] Nampeyo was considered a matriarch potter of the Hopi, who "stepped beyond the cultural confines and perceived expections of Hopi pottery by anthropologists." Her work and inventiveness pushed boundaries and techniques in ways that reverberated through subsequent generations of Hopi potters. She was singularly the first Native potter to be recognized nationally and internationally. Her influence had an effect on other pueblos and artists, and although she did not speak English she was sought out by scholars and dignitaries.[55]

The pueblos of Taos and Picuris, in the far north of New Mexico produce micaceous clay pottery with sparkling surfaces. These are often unornamented; the golden, reflective mica particles serve as a natural ornamentation.[48] The most southern Pueblo, Ysleta del Sur (Tigua Pueblo), located near El Paso, Texas, is not well known for pottery work, however it's potters produced, up until the 1930s, utility ware such as bowls, and tortilla irons (flatteners).[56]

Contemporary period

Starting in the 1960s, numerous artists, scholars, and curators began to exhibit and write about the work of contemporary Pueblo artists whose practices were cognizant of the past and its traditions while innovating new methods, processes and design sensibilites. Museums and private individuals began collecting these new forms of Native art, and by the 1980s a new market began to emerge.[50]

Knowledge of this work developed slowly. In 1969, the groundbreaking contemporary ceramics exhibition, Objects: USA, was organized, showing the work of 89 artists, however it included only three Native Americans. In the same year, a major survey exhibition of ceramics, American Craft Today: Poetry of the Physical, organized by the Museum of Art and Design, included 286 artists, only one of whom was Native American. A 1987 show at the Philbrook Museum of Art, The Eloquent Object: The Evolution of American Art in Craft Media since 1945, had a much higher percentage of Native artists. The exhibition catalog featured an essay by Lucy Lippard who had long been a supporter of multicultural arts awareness and a champion for the art of women and people of color. Then, in 2003, 2006 and 2012, the Museum of Art and Design presented a comprehensive series of exhibitions, Changing Hands: Art Without Reservation; all of the artists in these shows were Native artists who were emerging or established in their careers.[50]

Many contemporary Pueblo artists seek to transcend the anthropological and ethnographic interpretations of their work, or stereotypes of how Native ceramic art should "look" or what its conceptual framework should be. This diversity of approaches ruptures any lingering Eurocentric or academic notions of what constitutes modernism, and blows down these walls to reveal the complexities of Indigeneity in the postmodern art world. Peter Held has written that these contemporary Native ceramic artists have become "transdisciplinary producers of knowledge" and that: "(t)hese shifting paradigms are manifestations of social, political, technological, economic, ecological and cultural conditions. Contemporary Native artists incorporate real-world thinking into their practices."[50] Art collectors and scholars tend to create divisions within authenticity of old art and new art, as some believe older more traditional Native work that is "unadulterated by outside influences" and therefore more valuable. Bruce Bernstein, curator of the Ralph T. Coe Center for the Arts and tribal historic preservation officer of Pojoaque Pueblo writes that "Measuring authenticity in this way sucks the agency out of Native people by negating their voice and replacing it with the 'tradition' or as a wholly freestanding one of 'Indian Art.'"[57] Simultaneously, Comanche art critic, Paul Chaat Smith has suggested that this culture trap is an "ideological prison" that is "capable of becoming an elixir that [we] Indian people ourselves find irresistible." Ceramic arts in general and Native American art in particular has often been relegated to the category of "craft" or "less advanced" than art from a European-descended historical framework. Contemporary Native American pottery is not always analyzed on its own merits, but rather it is considered as a "replication of existing forms" rather than contemporary art in its own right. Bernstein asks the question, "Why at such a late date as the twenty-first century, should we worry about whether something is traditional or not?"[57]

Tewa artist Jason Garcia (Oku Pin) of Santa Clara Pueblo descends from potters on both the maternal and paternal side, and learned pottery from his grandmother, mother and aunts; he is a grandson of the matriarch potter, Severa Tafoya. His work is exemplary in that it co-mingles traditional pottery techniques with technology, comic books, video games and 21st century pop culture to depict historic Pueblo warriors from the Pueblo Revolt alongside Marvel comic book heros Thor and Loki.[58][59] Rose Bean Simpson, another Santa Clara artist who frequently works in ceramics, believes art can bring about systemic changes by "building awareness around the energy of colonization, around indigenous culture, bodies, and place", and alleviate "Post Colonial Stress Disorder."[60] Native American modern and contemporary art, and Pueblo pottery and other "crafts" face a kind of double jeopardy because in the past not only have "craft-based media" been excluded from American art history, the field has frequently marginalized Native American art and the artists that make these works, relinquishing them to the realms of anthropology, folk art or special-interest niche genres. Native people's art has been left out of mainstream American art history because American Indian histories are misunderstood within American history, as Paul Chaat Smith calls "a constructed amnesia."[57]

See also

References

- Peckham, Stewart (1990). From This Earth: The Ancient Art of Pueblo Pottery. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press. ISBN 08-9013-204-6.

- Furst, Peter T.; Furst, Jill L. (1982). North American Indian Art. New York: Rizzoli. pp. 38–40, 66–71. ISBN 0-8478-0461-5.

- Dillingham, Rick (1994). Fourteen families in Pueblo pottery. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Duwe, Samuel (2020). Tewa Worlds: An Archaeological History of Being and Becoming in the Pueblo Southwest. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816540808.

- "Anasazi Pottery: Evolution of a Technology". Expedition Magazine. 35 (1). 1993. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- "Pottery Typology Project". New Mexico Office of Archaeological Studies. Retrieved 25 December 2020.

- Brody, J. J. (2005). Mimbres Painted Pottery. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press. ISBN 9781930618664.

- Gregory, David A.; Willcox, David A. (2007). Zuni Origins: Toward a New Synthesis of Southwestern Archaeology. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0816524860.

- Frank, Ross H. (1991). "The Changing Pueblo Indian Pottery Tradition: The Underside of Economic Development in Late Colonial New Mexico, 1750-1820". Journal of the Southwest. 33 (3): 282–321. JSTOR 40170025. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Stuart, David E; Moczygemba-McKinsey, Susan B. (2000). Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2179-8.

- "Pueblo Indian History". Crow Canyon Organization. Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Stuart, David E.; Moczygemba-McKinsey, Susan B. (2000). Anasazi America: Seventeen Centuries on the Road from Center Place. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-2179-8.

- Wenger, Gilbert R. (1991). The Story of Mesa Verde National Park. Colorado: Mesa Verde Museum. pp. 46–56. ISBN 0-937062-15-4.

- Chamberlain, Michael A. (Spring 2002). "Technology, Performance, and Intended Use: Glaze Ware jars in the Pueblo IV Rio Grande". Kiva Journal. 67 (3): 269–296. doi:10.1080/00231940.2002.11758459. JSTOR 30246398. S2CID 113672386. Retrieved 24 December 2020.

- Wilson, Gordon P. (2005). Guide to Ceramic Identification: Northern Rio Grande Valley and Galisteo Basin to AD 1700. Santa Fe: Laboratory of Anthropology, Museum of New Mexico.

- Franklin, Hawyard H. (2007). The Pottery of Pottery Mound, A Study of the 1979 UNM Field School Collections, Part 1: Typology and Chronology. Albuquerque: Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico.

- Hibben, Frank C. (1975). Kiva Art of the Anasazi at Pottery Mound. Las Vegas Nevada: K.C. Publishers.

- Schaafsma, ed., Polly (2007). New Perspectives on Pottery Mound Pueblo. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Liebmann, Matthew; Prucell, Robert; Aguillar, Joseph; Douglass, ed., John G.; Graves, William M. (2017). The Pueblo World Transformed: Alliances, Factionalism and Animosities in the Northern Rio Grande, 1680-1700, in the book New Mexico and the Pimería Alta: The Colonial Period in the American Southwest. University of Colorado Press. ISBN 978-1607325734. Retrieved 24 December 2020.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Abaytemarco, Michael (18 August 2017). "Origin Stories: Contemporary Native Potters". Pasatiempo Magazine, Santa Fe New Mexican. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- "Indian Pueblo Cultural Center". Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- "Indian Entities Recognized and Eligible To Receive Services From the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs" (PDF). United States Department of the Interior. Retrieved 31 December 2020.

- Sando, Joe (19 September 1999). "Pueblo Indians have survived countless struggles". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Rautman, Alison E.; Solometo, Julie P. (2018). "A Test of H. P. Mera's Ceramic Collection Strategy" (PDF). Southwest Pottery. 34 (1, 2). Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- Fowler, Andrew P. (1991). "Brown Ware and Red Ware Pottery: An Anasazi Ceramic Tradition". Kiva: Journal of the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society. 56 (2): 123–144. JSTOR 30247263. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Cassells, E. Steve (1997). The Archaeology of Colorado. Johnson Books. ISBN 978-1555661939.

- Huntley, Deborah L.; Clark, Jeffery J.; Ownby, Mary F. Movement of People and Pots in the Upper Gila Region of the American Southwest: in the book Exploring Cause and Explanation: Historical Ecology, Demography, and Movement in the American Southwest. Boulder: University of Colorado Press. JSTOR j.ctt1bz3w0j.21. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Kritzer, Rona; Stebbins, Marti; Bloom, Cyresa. "Pottery of the Ancestral Puebloan Indians" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- "Roosevelt Red Ware". American Southwest Virtual Museum, Arizona State University. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- Lyons, Patrick D. (Winter 2013). "Jeddito Yellow Ware: Migration, and the Kayenta Diaspora". Kiva, Special Issue on Jeddito Yellow Ware. 79 (2): 147–174. JSTOR 24544686. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Wilson, C. Dean. "Ware Name: Jeddito Yellow Ware". Office of Archaeological Studies: Pottery Typology Project. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- O'Brien, Melanie (1 April 2015). "Notice of Inventory Completion: U.S. Department of the Interior, NPS, Montezuma Castle National Monument, Camp Verde, Arizona". Federal Register, National Park Service. National Park Service. 80 (62): 17, 477–17, 479.

- Carlson, Roy L. (1963). "Basket Maker III Sites Near Durango, Colorado". University of Colorado Studies, Series in Anthropology. 8.

- Breiternitz, David A.; Rohn, Jr., Arthur H.; Morris, Elizabeth A. (1974). "Prehistoric Ceramics of the Mesa Verde Region". Museum of Northern Arizona, Ceramics Series. 5.

- "Testimony of Hands". Maxwell Museum of Anthropology, University of New Mexico. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Mallouf, Robert J. (Spring 1996). "An Unraveling Rope: The Looting of America's Past". American Indian Quarterly. 20 (2): 197–208. doi:10.2307/1185700. JSTOR 1185700. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Simmons, Cynthia R. (Summer 1979). "Vandalism is Robbing Us All" (PDF). Our Public Lands, Journal of the Bureau of Land Management, US Dept. Of Interior. 29 (3): 3–5. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- "Mimbres Pottery". Trafficking Culture. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Romeo, Nick (12 June 2015). "Living in the Past". Slate. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Colwell, Chip (1997). Plundered Skulls and Stolen Spirits. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226299044.

- Clemmer, Richard O. (2011). "Museum Collections and the Search for "Authentic Historical Consciousness" in the Age of Nationalist Imperialism" (PDF). Anthropos. 106: 69–85. doi:10.5771/0257-9774-2011-1-69.

- Sharp, Kathleen (November 2015). "An Exclusive Look at the Greatest Haul of Native American Artifacts, Ever". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Taylor, Phil (25 June 2009). "Deaths of Artifact Looting Suspects Generate Political Blowback for Interior, Justice". New York Times. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- Paskus, Laura (18 August 2009). "Stealing the Past: Recent artifact raids shed light on today's looting syndicate and the damage it does to New Mexico's history". Santa Fe Reporter. Retrieved 9 January 2021.

- Dillingham, Rick; Elliott, Melinda (1992). Acoma & Laguna Pottery. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press. ISBN 0-933452-32-2.

- Gladwin, Harold S.; Haury, Emil W.; Sayles, E.B.; Gladwin, Nora (1965). Excavations at Snaketown: Material Culture. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press.

- Lammon, Dwight P. (Winter 2005). "Pueblo man-woman potters and the pottery made by the Laguna man-woman, Arroh-a-och". American Indian Art Magazine. 31 (1).

- Dingmann, Tracy (19 September 1999). "Pueblo pottery becomes fine craft". Albuquerque Journal. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Blair, Mary Ellen; Blair, Laurence (1986). Margaret Tafoya: A Tewa Potter's Heritage and Legacy. West Chester, Pennsylvania: Schiffler Publishing. ISBN 0-88740-080-9.

- Held, Peter; King, editor, Charles S. (2017). Tempered by Time: Modern and Contemporary Ceramics, in the book Spoken Through Clay: Native Pottery of the Southwest. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press. pp. 15–19. ISBN 9780890136249.

- Peterson, Susan (1977). The Living Tradition of Maria Martinez. New York: Kodansha America, Inc. ISBN 0-87011-497-2.

- "San Juan 1930 Pottery Revival". Salazar Rio Grande del Norte Center, Luther Bean Museum. Retrieved 7 January 2021.

- "Nampeyo Showcase". Arizona State Museum. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Nampeyo of Hano (1857-1942)". Bowers Museum. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- King, Charles S. (2017). Voices in Clay, in the book Spoken Through Clay:ative Pottery of the Southwest. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press. pp. 21–23. ISBN 9780890136249.

- Houser, Nicholas P. (Winter 1970). "The Tigua Settlement of Ysleta del Sur". Kiva: Journal of the Arizona Archaeological and Historical Society. 36 (2): 23–39. JSTOR 30247133. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Bernstein, Bruce (2005). It's Art: "Keep talking while we keep working, but hold it down so I can hear myself think" in the book Changing Hands Art Without Reservation 2: Contemporary Native North American Art from the West, Northwest and Pacific. New York: Museum of Arts and Design. pp. 176–179. ISBN 1-890385-11-5.

- "Jason Garcia". Native Arts and Cultures. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- "Art Talks: Pueblo Warriors Jar by Jason Garcia Joins Rockwell Collection". Rockwell Museum, A Smithsonian Affiliate. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Duke, Ellie (9 March 2020). "Meet the US Southwest's Art Community: Rose B. Simpson Believes Culture Is for "Conscious Nurturing"". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 11 January 2021.