Prussian invasion of Holland

The Prussian invasion of Holland[1] was a Prussian military campaign in September–October 1787 to restore the Orange stadtholderate in the Dutch Republic against the rise of the democratic Patriot movement.

| Prussian invasion of Holland | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Patriot era | |||||||

Prussian troops entering the Leidsepoort of Amsterdam on 10 October 1787. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

20,000 Prussians 6,000 Orangists | 20,000 Patriot volunteers, Legion of Salm | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 211 deaths (71 killed, 140 died of disease) | unknown | ||||||

Background

The direct cause was the arrest at Goejanverwellesluis (actually Bonrepas) of Stadtholder William V of Orange's wife, Wilhelmina of Prussia, on 28 June 1787. She was on her way from Nijmegen, where William V had taken refuge, to The Hague, where she intended to request her husband to be allowed to return to, after the States of Holland had fired him as Captain General of their troops in 1786.This had not been done on a whim: the decision to travel to The Hague had only been taken after Gijsbert Karel van Hogendorp had undertaken a secret mission to the Orangist leaders in that city to discuss its advisability, because her husband was, as usual, hesitating about what course of action to follow. The leader of the Orangist party in The Hague, the British envoy James Harris saw possibilities to put pressure on the States of Holland if the Princess suddenly arrived, and he told van Hogendorp to give the green light to the Princess, who was with her husband in the armed camp of the Dutch States Army in Amersfoort. The stadtholder then grudgingly gave his consent.[2]

The Princess then returned to Nijmegen, while preparations for the journey to The Hague were made by ordering fresh horses for her carriages along the route in two places. This caused suspicion among the Patriot Free Corps in the area, who in this way were alerted to her supposedly secret travel plans. The military authorities posted Free Corps patrols in the affected area with orders to intercept her. When on 28 June 1798 she departed from Nijmegen to The Hague with a small retinue (a chamberlain, a lady in waiting, and two officers, colonel Rudolph Bentinck, an adjutant of the stadtholder, and Frederick Stamford, the military tutor of her sons), but no armed escort (Harris had advised it was safe enough to only take a bag of gold along to bribe Patriot Free Corps with[3]) she was indeed intercepted near Goejanverwellesluis by a Free Corps patrol from Gouda. She was not mistreated, as has been asserted by Orangist propagandists, but only temporarily detained in a nearby farm, to await the arrival of members of the Military Commission in Woerden. The only untoward thing that happened was that the leader of the patrol drew his saber, but he put it back in its scabbard when requested. When the Military Commission arrived she was told she would not be allowed to proceed to The Hague, for fear of instigating public unrest there, but she was immediately released, and allowed to return to Nijmegen.[4]

Diplomatic preliminaries

Meanwhile, Harris in The Hague was worried about the lack of news about the Princess. He was playing cards with the French envoy Vérac that evening, and was so off his game that he lost a lot of money. As soon as he received news about the interception, he regained his composure, and started to take advantage of the situation, thereby supporting the suspicion on the part of the French and the Patriots that he had all the time conspired to bring the event about, and that it was no more than a provocation. And this was more or less the consensus in diplomatic circles in The Hague, though hypotheses about who actually conspired with whom varied.[5]

In any case, the Princess, back in Nijmegen, on 29 June wrote letters of complaint to her husband's nephew, king George III of the United Kingdom, and her brother king Frederick William II of Prussia. Her husband was little help: he wrote to his daughter, Princess Louise: "The misfortune which I foresaw has happened ... I was always against this journey and in my misfortune it is a great consolation that I did what was in my power to stop it and to dissuade your Mother from such a risky venture."[6]

Though the Princess did not expect much from her brother at first, her message fell onto fertile ground. Since the death of his predecessor Frederick the Great the previous year, the new king had given new hope to the pro-British court party around minister Hertzberg, and lessened the influence of the pro-French party of Hertzberg's rival, minister Finckenstein. Hertzberg was opposed to the alliance between France and Austria which at the time held the upper hand on the European Continent, and the détente the old Prussian king had maintained with France, and which had previously held Prussia back from all too aggressive interventions in the Dutch Republic that might offend France. The incident with the Princess played into his hands. Fredrick William's first impulse was rage; he instructed the Prussian envoy in The Hague, Thulemeyer to protest to the States General of the Netherlands about the insult to his sister, and to demand from the States of Holland that they would give her satisfaction, though this protest did not yet take the form of an ultimatum.[7]

The Princess saw the possibilities immediately: she wrote a letter to her brother on 13 July in which she proposed that he would use the situation to bring about the restoration of her husband to his office of Captain-General and to liberate the Republic from the Patriots. But she overplayed her hand, because at this time Frederick was only interested in an apology, and did not conflate this with something that might frustrate the attempts at mediation France and Prussia had previously made. Stamford, who had conveyed the Princess's letter by hand, heard the king exclaim: "The b... wants to draw me into a war, but I'll show her that she doesn't lead me."[Note 1] Envoy Thulemeyer also played a moderating role, be it with questionable means, as he lied both to the Dutch politicians and his own government about what either had actually said, so as to calm tempers on both sides. When the Princess became aware of this double play, she started to work for Thulemeyer's recall. Thulemeyer also tried to cool the Prussian ardor by exaggerating the rumors about French preparations for war in case of a Prussian intervention in the form of establishing an armed camp in Givet on the border between France and the neutral Prince-Bishopric of Liège, that provided a theoretical route for a French army to the Netherlands, that circumvented the Austrian Netherlands.[8]

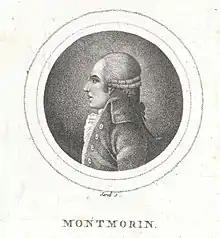

The camp in Givet was not entirely a figment of people's imaginations, as the first response of the French government to the threatening language of the Prussian king (and the movements to the Dutch border at Wesel of Prussian troops) had indeed been to erect such a camp, and to garrison it with a formidable military force (15,000 men). But these rumors had on 29 June elicited a threatening diplomatic note from the British government that had given France pause. For the moment the French pretended that the alleged military build-up was just intended to "train the troops" and the preparations actually had halted. But around the end of July the French Cabinet appears to have seriously discussed the plan to mount such a force. The minister of Foreign Affairs, Montmorin, and the minister for War, de Ségur, were in favor, but the Finance Minister Brienne vetoed the plan, for lack of money.[Note 2] From that time on the Camp of Givet was nothing more than a French bluff to keep the Prussians and British guessing, and the Patriots hoping.[9]

The reason why the British government was so alert to French military moves, was that the British Cabinet of Prime Minister William Pitt and Foreign Secretary Carmarthen had just in May fully endorsed the policy of active support of the "British" party (i.e. the Orangists) in the Republic, together with a campaign of subversion, espoused by Harris. Harris was of necessity (as Carmarthen offered little guidance) an envoy who not so much executed foreign policy, as made it. Ever since he arrived in the Dutch Republic at the end of 1784 he had immersed himself in its politics, and become the de facto leader of the Orangists. He had surrounded himself with agents of influence, like the Zeeland pensionaries Van de Spiegel and Van Citters, and other secret agents, like baron van Kinckel and count Charles Bentinck, who not only gathered intelligence, but actively took part in secret operations. At first his financial outlays had been relatively modest, on the same scale as those of his French colleague Vérac,[10] but in May he had conceived a plan on a far larger scale. The immediate cause was that the Orangist States of Gelderland, who were financing the States Army troops that the States of Holland had tried to recall to the Holland borders in 1786, were now in severe financial difficulties, because of this unusual extra expense. Harris estimated that he needed £70,000[Note 3] to support Gelderland. The Cabinet granted these funds, money to be laundered through the Civil list of king George with his grudging approval.[11] It was clear that other expenses of the campaign of subversion also would be financed from this slush fund. Once he returned to the Republic Harris' agents swarmed out to bribe officers of several States Army regiments, paid by the States of Holland, to defect.[12] The States were forced by their success to cashier a large number of officers whose loyalty was in doubt. This caused a tug of war with the other provinces in the States-General in June with parliamentary chicanes around the status of the delegations of the rival States of Utrecht determining temporary 4-3 majorities for either the Patriot or the Orangist side in the States General.[Note 4] Eventually there was a complete breach between the States of Holland and the majority of the States General (the provinces of Zeeland, Gelderland, Friesland and Utrecht (Amersfoort)) at the end of June[13] In sum, Harris' efforts severely undermined the military power of the Patriot States of Holland, which might have shifted the balance of military power to the stadtholder, if it had come to a full-blown civil war. For that reason the States of Holland on 23 June (so before the incident at Goejanverwellesluis) passed a resolution asking for mediation between the warring parties in the Republic by France.[14]

Diplomatic mediation, far from being a form of conflict resolution by a neutral third party, could more cynically be defined as the imposition of a political arrangement on often unwilling parties by one or more foreign powers, with their own agenda that determined the contents of the arrangement. France had certainly its own ideas about what the arrangement should be: the return to either the Dutch constitution during the two "stadtholderless periods" of 1650-1672 and 1702-1747, or at least to the era in which the formal powers of the stadtholder were far less than after 1747 (for instance like under the stadtholderate of Frederick Henry). On the other hand, the French king had been adamant that he did not want any "democratic" experiments in the Dutch Republic. As a matter of fact, the position of Vérac, who had actively supported the "democrats", had been much weakened after the death of Vergennes and the fall of Calonne in early 1787, and his recall would follow just before the diplomatic situation exploded in September 1787, at exactly the wrong moment. The "solution" that a French mediation would supply would therefore satisfy the "aristocratic" Patriots, but would severely disappoint the "democratic" Patriots. But despite this hidden French agenda, Vérac (and his colleague Jean-François de Bourgoing, who had joined him as a special envoy in the Spring of 1787) kept indicating a willingness to support the Patriots (of both varieties) militarily. At the request of Vérac, the new French Foreign Minister Montmorin authorized on 7 July the surreptitious sending of two detachments of 50 engineers and one of 50 gunners to the Military Commission in Woerden. They arrived in small groups, in civilian clothing, but Harris soon discovered the covert operation.[15]

Though the States of Holland preferred French mediation, there were obviously other candidates. Prussia had offered its "good offices" long before the incident at Goejanverwellesluis, and sent Johann Eustach von Görtz to mediate between the stadtholder and the "aristocratic" Patriots in the Fall of 1786. Obviously, his idea of a "solution" was biased more in the direction of the situation as it had been before 1780, but he was open to a compromise, that would take away the main grievances of the "aristocratic" Patriots, which implied a weakening of the position of the stadtholder. Von Görtz had achieved little, however. After the request by the States of Holland for French mediation, that France accepted on 18 July, the matter became more urgent for the Prussians, however, even without the complication of the incident at Goejanverwellesluis. Montmorin gave them an opening when on 13 July he asked if the Prussians would be interested in joint mediation, and proposed a package that would consist of a number of de-escalating military steps in the Republic; the renunciation by the States of Holland of their support for the demands of the democrats; the suppression of the virulent Patriot press; and some kind of "satisfaction" to be offered by the States of Holland to the Princess, in the form of an invitation to visit The Hague.[16]

This may sound reasonable, but unfortunately for Montmorin these proposals were unacceptable for the Patriots. Their view was that the incident with the Princess was a non-event; that she had been treated politely enough, and that her temporary detention was her own fault; that the States of Holland were fully within their rights to prevent her from coming to The Hague to preserve public order; that therefore there had been no insult, and there was no need for an apology, let alone "satisfaction." And this on 14 July had been the reply to Frederick William's diplomatic protest of early July.[17] The Prussian king, not pleased that he was not taken seriously, now decided to concentrate a force of 20,000 soldiers near Wesel on the Prussian-Dutch border, and to offer the command over this force to the Duke of Brunswick. But even on 8 August he indicated behind the scenes that this did not imply a fixed intent to initiate military steps. This would depend on a more satisfying attitude by the States of Holland.[18]

However, this was a political impossibility for the States of Holland: for the democrats the admission of the Princess to The Hague had acquired great symbolic significance. If the "triumvirate" of "aristocratic" Patriot pensionaries (Zeebergh, de Gijselaar, and van Berckel) and the Grand Pensionary Pieter van Bleiswijk would accede to the Prussian demand, that would cause a popular insurrection against them.[19] The lack of a positive reaction of the Holland government caused a shift in the stance of the Prussian government, promoted by Hertzberg, who was assisted by a "leak" of the British government to the Prussians of its correspondence with the French government about its demand to be allowed to join the mediation. This made clear that the French already had acceded to this demand, without informing the Prussians. It also became clear that the British were far more enthusiastic about putting pressure on the Patriots than the French. Harris always had sonorously given as his motive his respect for "the Ancient Dutch Constitution" (by which he meant the arrangement that had been instituted in 1747 and was therefore at the time only forty years old) that had to be Restored (also because it implicitly guaranteed British "rights" to a preponderant position in the Low Countries in the name of maintaining the Balance of Power on the Continent). This fully complied with the Orangist position in the conflict with the Patriots. In other words, the British standpoint was incompatible with the French one as a basis for a compromise to be imposed in the mediation. But it was attractive to Prussia, because the British fully supported the king's demand for "satisfaction", and they encouraged him to take military steps.[20]

The French started to become nervous because of these developments, and Montmorin warned the Patriots on 18 August that they had to accommodate the Prussians, as France was not ready to be dragged into a war on their behalf. But the Patriots ignored him. Vérac's position became untenable due to his apparent lack of influence on the Patriots, who appeared to have taken the bit between their teeth, and he was recalled on 20 August; he was temporarily succeeded by Antoine-Bernard Caillard as Chargé d'affaires on 10 September. Around this time there also was a government crisis in France, as Brienne was appointed "premier ministre" by king Louis, and de Ségur resigned in protest. As a consequence France was without a minister for War during the crucial month of September 1787.[21]

Meanwhile, the French bluff about the armed camp at Givet had been discovered by the British who had sent out several spies to the area and seen no troops there. The British Cabinet also sent William Grenville to the Netherlands for a fact-finding mission, and he sent in a report that fully supported Harris' policy. Both pieces of information hardened the position of the British government. King George had in June declared that it was impossible for the country to go to war, but in early August he indicated his approval for Harris' policies. As a consequence, the British approaches to Prussia were becoming more specific. The government sent general Fawcett to the Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel to negotiate the hiring of mercenary troops, to be used to support a possible Prussian military intervention. Though the treaty with the Landgrave for 12,000 troops was eventually only signed on 28 September, the gesture was sufficient for the Prussians to be assured of the British bona fides.[22]

Together with the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War on 19 August[Note 5] this decided the Prussian king in favor of an invasion of Holland. Brunswick advised him that if he wanted to go through with it, it had to be before October, as the weather would otherwise make a campaign impossible. On 3 September the British envoy in Berlin, Joseph Ewart, presented a note in which an agreement was proposed for Anglo-Prussian cooperation in operations against the Dutch. The common objective was to be the restoration of the stadtholder to his former position. The Prussian army was to remain encamped in Gelderland for the duration of the Winter, whatever the outcome of the conflict, and Britain would subsidize the expenses. Britain would hire German troops to support the Prussians. Britain would warn France that if it tried to intervene, Britain would mobilize its sea and land forces. Prussia and Britain would act in concert in further measures.[23] After that events developed rapidly.

The Campaign

The ultimatum issued on 9 September 1787 by the Prussian ambassador Thulemeyer to the States of Holland [Note 6] mentioned only one casus belli: It asked

...that their Noble and Great Mightinesses agree to punish, at the request of the Princess, those who would be considered culpable of offenses against Her August Person.[Note 7]

In other words, the Prussian war aims were quite limited, and intentionally so, firstly to avoid being seen as unreasonable by the other European Great Powers, and secondly, because the Prussian king had at this stage no intention of overturning the Holland government, possibly obligating him to engage in a lengthy and costly occupation. The matter was supposed to be resolved in a fortnight, and therefore the troops were only provisioned for a campaign of short duration.[24]

The command of the invading troops was entrusted to Generalfeldmarschall Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, coincidentally a nephew of Duke Louis Ernest of Brunswick-Lüneburg, the old mentor of William V. His army consisted of about 20,000 Prussian soldiers, in three divisions, commanded by the generals Lottum, Gaudi and Knobelsdorff. After the ultimatum had expired (the States of Holland had not replied to it, at the counsel of pensionary Adriaan van Zeebergh) they marched on 13 September 1787 from their starting line at Zyfflich to Nijmegen, where they were joined by the troops of the garrison of the Dutch States Army in that city under command of the stadtholder.[25] The Prussian government had asked permission from the States of Gelderland, Utrecht and Overijssel for the march through those lands, as their conflict was with Holland only.[26] After entering the Netherlands, the Prussian army split in its three components, which marched in three columns: Knobelsdorff, together with the Duke, took the Southern route along the river Waal to the fortress city of Gorinchem. Gaudi's division split in two detachments after Arnhem, and marched on both banks of the river Rhine towards Utrecht. Finally, Lottum's division, mainly cavalry, moved North-West from Arnhem to the Veluwe and ultimately the coast of the Zuiderzee toward the Eastern border of Holland, and the Hollandse Waterlinie. In theory they could expect resistance from the Patriot troops in the city of Utrecht and in fortifications along the Rhine near Jutphaas and Vreeswijk (mostly members of Free Corps and the "Legion of Salm"[Note 8]) and the States Army garrisons of a number of fortress cities (Gorinchem, Naarden, Woerden, Weesp), and the capital in those days, The Hague, who had been withdrawn in October 1786 from the command of the stadtholder by the States of Holland. But the loyalty of these mercenary troops was very doubtful, in view of the wholesale desertions during the preceding months. Besides the Nijmegen garrison of the States Army, the Prussian troops could count on the support of the States Army garrisons of Amersfoort and Zeist, who were more or less besieging Utrecht from a distance.[27]

The Gaudi division was supposed to attack Utrecht and the fortifications South of that city, but this proved unnecessary. The Rhinegrave was very aware of the strategic danger that the two-pronged attack (north and south of the city) posed. It was likely that the Prussians simply would pass him by and encircle the city, in which case his main force would become entrapped, and the Hague would become endangered. For that reason he asked the Defense Council in Woerden, that was in nominal command of the Holland troops in Utrecht, on 14 September for permission to evacuate Utrecht the next day, and to retreat to Amsterdam where he proposed to make a stand. The only hope of the Patriots appeared to be to hold out until they could be relieved by a French army that was rumored to stand ready in Givet on the border of France and the neutral Prince-Bishopric of Liège to march to the Netherlands, so if the Patriots could defend Amsterdam long enough for the French to arrive, they might still be saved. The permission was given and the evacuation started the next day and soon degenerated into total chaos. The Free Corps became totally demoralized and threw away their arms. Only the Legion of Salm maintained its composure and reached the outskirts of Amsterdam on the 16th. But the Prussians were able to occupy Utrecht unopposed the same day, and move on to The Hague.[28]

The fortress city of Gorinchem (the only garrison south of Amsterdam still in a position to offer resistance, after the Woerden Defense Council had ordered all other troops to retreat to Amsterdam on 15 September) was ordered to surrender by Knobelsdorff on 17 September. The town was commanded by Alexander van der Capellen, a brother of the Patriot leader Robert Jasper van der Capellen. He recognized that his position was hopeless due to the lack of preparations for a siege. Furthermore, a few weeks earlier the two States Army regiments that had been garrisoned in the city had been bribed by one of Harris' agents to defect wholesale, taking their cannon with them.[29] The only defenders left were Free Corps. He therefore capitulated after a token bombardment by the Prussians, and he and his troops were made prisoners of war and transported to Wesel, where he was treated so badly, that he died in December 1787. The road to Dordrecht and Rotterdam lay now completely open for the Prussians.[30]

The divisions of Gaudi and Knobelsdorff now marched together to Schoonhoven where the defense line proved to be evacuated, so that the Prussian troops and their States-Army companions could march unhindered to The Hague. In that city a revolution had meanwhile taken place. On 15 September the "triumvirate" of the pensionaries Zeebergh, de Gijselaar, and van Berckel had proposed to the States of Holland that they also should move to Amsterdam, as The Hague was no longer safe. However, a few Holland cities that still were in Orangist hands, and the Holland ridderschap (College of Nobles) opposed the move, so that only the delegations of the Patriot cities actually moved to Amsterdam the next day. The rump-States of Holland that remained in The Hague then assumed power and started on 19 September to repeal all Patriot-tinged legislation of the previous years, starting with the reinstatement of the stadtholder in his offices of Captain-General of the States Army and Admiral-General of the Navy. William V returned to The Hague on 20 September at the head of his States-Army troops, and the Hague garrison, that up to that moment had nominally opposed him, fell immediately in line. The Hague Orangist mob started looting Patriot homes, and the soldiers heartily joined in.[31]

One of the consequences of the reconstitution of the States of Holland in The Hague was that this body could order the States-Army garrisons of a number of the fortress towns behind the Hollandse Waterlinie to offer no resistance to the advancing Prussians. Naarden, under the command of the Patriot leader Adam Gerard Mappa, surrendered for that reason on 27 September, as did nearby Weesp. This enabled Lottum, who had up to that moment made little progress, to approach Amsterdam closely from the East.[32] The main Prussian force of Gaudi and Knobelsdorff under personal command of the Duke had reached Leimuiden on the 23rd. The next day he had Amstelveen reconnoitered, where there was a strong defensive line of the Patriot forces in Amsterdam. The entire region had been inundated, so that the city could only be approached along a number of narrow dikes and dams that could easily be defended. The defensive line formed a crescent from Halfweg, West of Amsterdam, via Amstelveen to the South, to Muiden, East of Amsterdam. But the commanders of the troops in Amsterdam realized that they could not expect to survive a Prussian assault. They desperately tried to temporize by asking for a ceasefire and negotiations. An Amsterdam delegation consisting of Abbema, Gales, Goll and Luden arrived in Leimuiden on 26 September to offer terms, but the Duke replied to their request with the remark that they could best adhere to the resolution that the rump-States of Holland were about to adopt in which they meekly asked the Princess what she required to satisfy her honor. The deputation returned to the Amsterdam vroedschap with this answer and a new deputation was sent to The Hague on the 29th to do this. The Duke visited the Princess incognito on the 28th to urge her to accept the overtures of the Amsterdam delegation, because he had little desire to attack Amsterdam, whose defenses he considered too formidable.[33]

However, he was met at the stadtholder's residence not only by the Princess and her husband, but by a cabal of Orangists, including the British ambassador Sir James Harris; the Grand Pensionary of Zeeland, Laurens Pieter van de Spiegel; the author of the declaratoir (proclamation) of the stadtholder of May 1787, and tutor of the stadtholder's sons, Herman Tollius; the Zeeland Orangist Willem Aarnoud van Citters; and another protégé of Harris, A.J. Royer, the secretary of the States of Holland; who all advised that it would be tactically better to put more pressure on the Amsterdam delegation, so as to elicit not so much the required apology to the Princess, as the total submission of the Patriots, in Amsterdam and elsewhere. It was agreed that the Duke would end the ceasefire with Amsterdam at 8 PM on 30 September, and attack the city's defenses on 1 October.[34]

Up to this moment the Prussian campaign had been a militärischer Spaziergang (military promenade), but things were not going to be so easy from now on. First of all, the terrain between Leimuiden and the defense line around Amsterdam was very difficult. On the left-hand side there was the Haarlemmermeer, a large lake that shielded Amsterdam on the South-West flank.[Note 9] The terrain to the East of the lake was mainly peat bog, suitable only for animal husbandry and crisscrossed with creeks and ditches. In addition large sections were intentionally flooded closer to Amsterdam, and could only be traversed across dikes and dams that were protected with sconces and other earthworks. The area was bisected by the meandering Amstel river, that was only spanned by a few bridges, so that troops marching from the South were forced to divide in two columns that could not easily support one another.

The defenders of Amsterdam were mainly elements of Free Corps from all over the Netherlands, who had been forced to retreat to the Amsterdam redoubt as a last resort. Besides the remnants of the Utrecht defense force, that had so hastily retreated on 16 September, there were also Frisian Patriots, who had lost the Frisian civil war between the rival Leeuwarden and Franeker "States of Friesland" earlier in the month, with Johan Valckenaer and Court Lambertus van Beyma (at this time still on speaking terms) in the van. Both groups had little military value, especially as they were very demoralized. The Rhinegrave was very unpopular, and quietly resigned his command, when he reached Amsterdam. He was replaced by the French veteran of the American Revolutionary War, Jean Baptiste Ternant, who had been seconded by the French government, together with a few hundred gunners. He had tried in vain to organize the Patriot defenses in Overijssel, but that province went over to the Orangists without a fight. The most credible part of the defenders consisted of the Amsterdam schutterij and the Free Corps. Colonel Isaac van Goudoever was still in charge of the "white" regiment of the schutterij, but just around this time he had been forced to take to bed, because of a leg injury.[35]

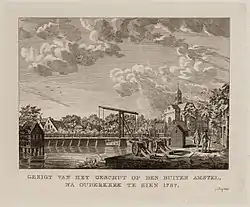

The Prussian operational plan for the attack on 1 October consisted of a five-pronged approach.[Note 10] The most audacious part was an amphibious landing by 2,000 troops, transported from Aalsmeer on flat-bottomed boats across the Haarlemmermeer to Sloten. This landing circumvented the earthwork at Halfweg, that otherwise might have been a major obstacle, because it dominated the narrow isthmus between the Haarlemmermeer and the IJ river.[Note 11] The defenders were surprised, and the road to Amsterdam from Haarlem lay open. The Prussian troops then turned South toward Amstelveen where they arrived just in time to support the main frontal attack by a force of 4,000 Prussians earlier in the day. Amstelveen had until it was attacked in the rear by the Prussians from Sloten, valiantly held on under the command of Colonel count Guillaume de Portes,[Note 12] but the defenders had to retreat in the direction of Ouderkerk aan de Amstel, thereby opening the way to Amsterdam from the South.[36]

The village of Ouderkerk itself had been the target of two other attack prongs that morning. It was an important strategic object, because the village had the only bridge across the Amstel river outside Amsterdam, which was essential for the communications between the Prussian troops on either side of the river. The village was occupied by Amsterdam schutters under the command of colonel George Hendrik de Wilde after it had been evacuated by States Army troops on the Holland repartitie[Note 13] who had previously been positioned there, on 23 September. The schutters manned several batteries of 3-pdr. and 6-pdr. field guns on the banks of the Amstel and the Holendrecht (a creek that flows into the Amstel just upstream of where the bridge was located). This enabled them to oppose two Prussian columns that approached the village along the West bank of the Amstel from Uithoorn, and along the Holendrecht from Abcoude. The murderous shrapnel fire of the Patriot guns repelled several attacks by both columns, causing relatively heavy Prussian casualties. The village remained in Patriot hands until the troops were withdrawn the next day, because the fall of the Amstelveen outpost had opened the way to the inner defenses of Amsterdam for the Prussians anyway[37]

The final attack-prong was an assault, again launched from Abcoude, along the Gein and Gaasp rivers to Duivendrecht, on the Eastern approaches to Amsterdam. Here the Prussians were also repelled by a battery of Amsterdam schutters. In the next days the Prussian soldiers ransacked the summer residence of the Amsterdam Patriot burgemeester Hendrik Daniëlsz Hooft.[Note 14] In any case the road to the Muiden Gate in the Amsterdam inner defenses remained closed.[38]

Those inner defenses remained a formidable obstacle. They consisted of fortifications, completed in 1663, according to the bastion fort-model perfected in the 17th century. They consisted of 26 bastions that completely encircled the city behind a deep moat (now the Singel canal). There was plenty of artillery available, though trained gunners were in short supply (despite the addition of 200 French gunners, seconded by the French government). The Prussian army lacked a proper siege train, though it of course had its field artillery, that it now could bring within close enough range to bombard the inner city, if necessary. But the Prussian supply of artillery shot had grown rather sparse: only 200 were remaining for the moment. The Duke therefore was rather pessimistic about the prospect of a lengthy siege. He decided not to press the attack immediately, also because he wanted to avoid desperate measures by the defenders like the so-called "large inundation": a breach of the sea dikes at Sloterdijk and Zeeburg, which would devastate the countryside, but certainly would force the Prussians to withdraw. But he need not have worried. The Amsterdam city government decided to ask for a ceasefire in the evening of 1 October, which the Duke granted on 2 October.[39]

The same day a deputation of the city government left for The Hague to start negotiating with the Orangist States of Holland. At first it tried to bluff its way out of giving in to demands for total adherence to the resolutions of 19 September. It insisted on keeping the current city government in power and maintaining the right of the people to elect its representatives. But on 3 October it became clear that all hope of French intervention was lost.[Note 15] The city government therefore acceded to all Orangist political demands, but attempted to get favorable terms for the surrender from the Duke. Indeed he agreed not to occupy the city, but to limit himself to a symbolic occupation of the Leiden city gate. The French soldiers, and the remnants of the Legion of Salm and the "flying brigade" of Mappa were given safe conduct to the Generality Lands, and left on 7 October. The same day the Patriot members of the vroedschap stayed at home, and the members they had replaced in May occupied their seats again. On 9 October burgemeesters Dedel and Beels assumed their posts again, while Hooft stayed home. The situation before 21 April had been restored. On 10 October the restored city government signed the capitulation of the city, and 150 Prussians occupied the Leiden Gate.[40]

The new city government was not safe until the Free Corps and the schutterij had been disarmed. This happened in the following weeks, while 2,000 States Army troops garrisoned the city to help keep order. The Patriot press was suppressed, and the expression of Orangist sentiments again encouraged (by repealing the prohibition against wearing orange colors in public; now the wearing of the black Patriot cockades was prohibited). Meanwhile, in The Hague, the final formalities of the Orange Restoration were taken care of. On 8 October the Princess indicated that her honor would be satisfied if "the authors" of her humiliation in Goejanverwellesluis would forever be barred from holding public office (she supplied a list); the Free Corps in the entire country would be disarmed; and all regenten that had replaced Orangists in the preceding months would be removed again. At the suggestion of British Ambassador Harris she added that the criminal prosecution of the dismissed persons should remain a possibility. Harris wrote in his diary: "‘It is necessary to hold a rod of terror over the heads of these factious leaders, though it may, perhaps, not be to make use of it."[41]

If the States of Holland acceded to these wishes, she would ask her brother the Prussian king to remove his troops. Of course, the States did as asked: the people on her list were proscribed on 11 October. The Princess now was ready to do as she had promised, but the Prussian king had incurred great expenses that he wanted to be recompensed for. The Duke and the Princess negotiated him down from his initial demand of several million guilders, but he insisted on a "douceur" for the troops of exactly 402,018 guilders and 10 stuivers, to be paid by Amsterdam alone. But the States of Holland generously rounded this up to half-a-million guilders, to be paid by the entire province, and the king acquiesced.[42] As invasions go, this was a bargain: the victorious revolutionary French forces in 1795 demanded an indemnity of 100 million guilders for their "liberation" of the Netherlands from the stadtholder's dictatorship.

Aftermath

The Prussian invasion resulted in the Orange Restoration, bringing William V back into power, and causing many Patriots to flee to France. In 1795, the Patriots (now styling themselves "Batavians") returned with the support of revolutionary French troops, triggering the Batavian Revolution and ousting the Orangist regime. The old Dutch Republic was replaced by the Batavian Republic.

Notes

- "‘la B.... veut m'entraîner dans une guerre, mais f.... je lui montrerai bien qu'elle ne me mène pas".Cf. Colenbrander, p. 238, note 3

- De Ségur had estimated that the campaign would cost 14 million livres, which sum was simply not available. One wonders why the French did not simply ask the States of Holland to finance the French troops; Cf. Colenbrander, p. 244

- Colenbrander thinks that it was only £40,000, but Cobban corrects him; Cf. Colenbrander, p. 203, note 1; Cobban, p. 133, note 26

- At the time the rotating presidency of the States General was held by the delegation of Overijssel, a "Patriot" province, who provisionally seated the Patriot delegation of Utrecht, giving the Patriots a 4-3 majority. After an altercation between a delegate from Utrecht city, Jean Antoine d'Averhoult, and a delegate from Amersfoort, the lord Van Zuylen, who apparently fought a duel in the Hague Wood, the Amersfoort delegation was seated, giving the Orangist provinces the 4-3 majority; Cf. Colenbrander, p. 213

- The king had been afraid that if he started an invasion of the Republic, he might be attacked in Silesia by the Austrian emperor. As Austria was a Russian ally the war with Turkey meant that the emperor had his hands full, so there was no danger of such an attack; Cobban, p. 177

- And only the States of Holland; the States General of the Netherlands were not supposed to be "at fault" in the matter of the "insult" to the Princess.

- "...que Leurs Nobles et Grandes Puissances s'engageront de punir, à la requisition de la Princesse, ceux qui pourroient s'être rendus coupables d'offenses contre Son Auguste Personne."; Cf. Colenbrander, p. 290, note 1

- A kind of "private army", formed for the account of the States of Holland during the crisis of the Kettle War in 1784, in competition with the States Army, under the command of the Rhinegrave of Salm, who also commanded the city.

- Currently this is all dry land, as the lake was reclaimed in the 19th century. Amsterdam Airport Schiphol is located on the former lake bottom in the North-Eastern part of the former lake, close to the shore at the time

- Von Kleist has a detailed description of the Prussian order of battle and the orders issued to the troops; Cf. Von Kleist, pp. 27ff.

- Schaikowski (a Dutch translation of the German original of 1789 with the original maps) gives the dispositions of the several sconces that were part of the outer defenses of Amsterdam, and the inundations that surrounded them. Those maps will be useful to follow the description of the Prussian operations of 1 October.

- A detailed report of the hostilities at Amstelveen is given by de Mandach on the basis of colonel Comte de Portes' diaries; Cf. Mandach, pp. 105ff.

- These troops were mercenary regiments paid for by Holland according to the contribution formula (repartitie) that determined the financial contributions of the Dutch provinces to the defense budget of the Dutch Republic. Holland paid about 60% and so 60% of the States Army troops "belonged" to Holland. When stadtholder William V was relieved of the command of the Holland troops in 1786 this meant that Holland simply put a Defense Committee (the Committee in Woerden, referred to above) in charge of these troops in his place. But when William V was reinstated as Captain-General by the rump-States of Holland on 19 September, he ordered all these troops on 23 September to evacuate the garrison cities they had been stationed in, like Naarden, Weesp, and also Ouderkerk.

- The mansion, located on the bank of the Gaasp river, was called the Stolp. The damage was so large that Hooft had to live out his life at the residence of a relative; Cf. Hooft, H.G.A. and Hendrik Hooft Graafland (1999). Patriot and Patrician: To Holland and Ceylon in the Steps of Henrik Hooft and Pieter Ondaatje, Champions of Dutch Democracy. Science History Publications. p. 328.

- The Amsterdam city government had on 21 September sent a diplomatic note to the French government, carried by the Dutch consul in Bordeaux, Casparus Meyer, with a request for military intercession by king Louis XVI. The French cabinet was divided, and the British government threatened war if France interceded. The French minister of Foreign Affairs Montmorin told Meyer on 28 September that France was incapable of offering the requested assistance at this time. Meyer sent a message with this content to Amsterdam, that reached the city government only on 3 October; Cf. Colenbrander, pp. 272-275

References

- Scott, Hamish; Simms, Brendan (2007). Cultures of Power in Europe during the Long Eighteenth Century. Cambridge University Press. p. 278. ISBN 9781139463775. Retrieved 17 March 2016.

- Colenbrander, pp. 221-223

- Colenbrander, p. 224, note 2

- Colenbrander, pp. 224-226

- Cobban, p.151

- Cobban, p. 152

- Colenbrander, pp. 229-230

- Cobban, pp. 153-154

- Colenbrander, pp. 230-234, 242-243

- Cobban, p. 144

- Cobban, pp. 130-135

- Cobban, p. 137

- Cobban, pp. 136-137

- Cobban, p.138

- Cobban, pp. 138-147

- Colenbrander, p. 233; Cobban, pp. 155-157

- Colenbrander, p. 235

- Colenbrander, pp. 236-237

- Colenbrander, p. 237

- Colenbrander, pp. 240-241

- Cobban, pp. 164-165

- Cobban, pp. 168-173

- Cobban, pp.178-179

- Colenbrander, p. 276

- Colenbrander, p. 257

- Colenbrander, p. 277

- Colenbrander, pp. 257-259

- Colenbrander, pp. 259-266

- Cobban, p. 137

- Colenbrander, pp. 257-258, 264, 267

- Colenbrander, pp. 267-270

- Colenbrander, pp.282-283

- Colenbrander, pp. 283-284

- Colenbander, pp.283-285

- Colenbrander, pp. 277-281

- Colenbrander, p. 285

- Colenbrander, pp. 282, 285

- Colenbrander, p. 285

- Colenbrander, p. 286

- Colenbrander, pp. 286-287

- Colenbrander, pp. 288-289

- Colenbrander, pp. 288-291

Sources

- Cobban, A. (1954). Ambassadors and secret agents: the diplomacy of the first Earl of Malmesbury at the Hague. Jonathan Cape.

- Colenbrander, H.T. (1897). "De Patriottentijd, hoofdzakelijk naar buitenlandsche bescheiden, deel III: 1786-1787". Digitale Bibliotheek voor de Nederlandse Letteren (in Dutch). Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- F.W. von Kleist (1787). "Tagebuch von dem Preußischen Feldzug in Holland" (PDF). Familienverband derer v. Kleist e.V. (in German). Retrieved 18 April 2018.

- Mandach, C. de, and G. de Portes (1904). "Un gentilhomme suisse au service de la Hollande et de la France: Le comte Guillaume de Portes, 1750-1823, d'après des lettres et documents inédits". Google Books (in French). Perrin. Retrieved 22 April 2018.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Schaikowsky, C.G. von (1789). "Korte toelichting van alle schansen, welke tegen het eind van de maand september 1787 in de buurt van de beroemde stad Amsterdam zijn aangelegd, de daarop op de 1ste oktober 1787 onder aanvoering van de regerende heer hertog van Braunschweig, hoogvorstelijke doorluchtigheid, voorgevallen Pruisische aanvallen, benevens de aldaar voorbereide onderwaterzettingen bij een hiertoe behorende nauwkeurig vervaardigde kaart" (PDF). Stelling van Amsterdam (in Dutch). Bielefeld. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- Cor de Wit (1974): De Nederlandse revolutie van de achttiende eeuw 1780-1787. Oligarchie en proletariaat, Lindebauf

- Cor de Wit (1980): Oud en Modern. De Republiek 1780 - 1795 in Blok, D.P. (red) et al Algemene Geschiedenis der Nederlanden, Volume 9, Fibula-Van Dishoeck

.jpg.webp)