Protein methylation

Protein methylation is a type of post-translational modification featuring the addition of methyl groups to proteins. It can occur on the nitrogen-containing side-chains of arginine and lysine,[1][2] but also at the amino- and carboxy-termini of a number of different proteins. In biology, methyltransferases catalyze the methylation process, activated primarily by S-adenosylmethionine. Protein methylation has been most studied in histones, where the transfer of methyl groups from S-adenosyl methionine is catalyzed by histone methyltransferases. Histones that are methylated on certain residues can act epigenetically to repress or activate gene expression.[3][4]

Methylation by substrate

Multiple sites of proteins can be methylated. For some types of methylation, such as N-terminal methylation and prenylcysteine methylation, additional processing is required, whereas other types of methylation such as arginine methylation and lysine methylation do not require pre-processing.

Arginine

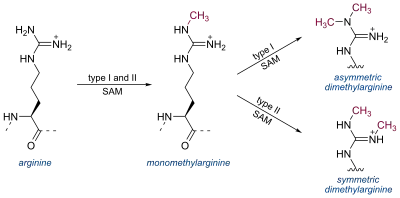

Arginine can be methylated once (monomethylated arginine) or twice (dimethylated arginine). Methylation of arginine residues is catalyzed by three different classes of protein arginine methyltransferases (PRMTs): Type I PRMTs (PRMT1, PRMT2, PRMT3, PRMT4, PRMT6, and PRMT8) attach two methyl groups to a single terminal nitrogen atom, producing asymmetric dimethylarginine (N G,N G-dimethylarginine). In contrast, type II PRMTs (PRMT5 and PRMT9) catalyze the formation of symmetric dimethylarginine with one methyl group on each terminal nitrogen (symmetric N G,N' G-dimethylarginine). Type I and II PRMTs both generate N G-monomethylarginine intermediates; PRMT7, the only known type III PRMT, produces only monomethylated arginine. [5]

Arginine-methylation usually occurs at glycine and arginine-rich regions referred to as "GAR motifs",[6] which is likely due to the enhanced flexibility of these regions that enables insertion of arginine into the PRMT active site. Nevertheless, PRMTs with non-GAR consensus sequences exist.[5] PRMTs are present in the nucleus as well as in the cytoplasm. In interactions of proteins with nucleic acids, arginine residues are important hydrogen bond donors for the phosphate backbone — many arginine-methylated proteins have been found to interact with DNA or RNA.[6][7]

Enzymes that facilitate histone acetylation as well as histones themselves can be arginine methylated. Arginine methylation affects the interactions between proteins and has been implicated in a variety of cellular processes, including protein trafficking, signal transduction and transcriptional regulation.[6] In epigenetics, arginine methylation of histones H3 and H4 is associated with a more accessible chromatin structure and thus higher levels of transcription. The existence of arginine demethylases that could reverse arginine methylation is controversial.[5]

Lysine

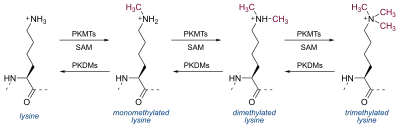

Lysine can be methylated once, twice, or three times by lysine methyltransferases (PKMTs).[8] Most lysine methyltransferases contain an evolutionarily conserved SET domain, which possesses S-adenosylmethionine-dependent methyltransferase activity, but are structurally distinct from other S-adenosylmethionine binding proteins. Lysine methylation plays a central part in how histones interact with proteins.[9] Lysine methylation can be reverted by lysine demethylases (PKDMs).[8]

Different SET domain-containing proteins possess distinct substrate specificities. For example, SET1, SET7 and MLL methylate lysine 4 of histone H3, whereas Suv39h1, ESET and G9a specifically methylate lysine 9 of histone H3. Methylation at lysine 4 and lysine 9 are mutually exclusive and the epigenetic consequences of site-specific methylation are diametrically opposed: Methylation at lysine 4 correlates with an active state of transcription, whereas methylation at lysine 9 is associated with transcriptional repression and heterochromatin. Other lysine residues on histone H3 and histone H4 are also important sites of methylation by specific SET domain-containing enzymes. Although histones are the prime target of lysine methyltransferases, other cellular proteins carry N-methyllysine residues, including elongation factor 1A and the calcium sensing protein calmodulin.[9]

N-terminal methylation

Many eukaryotic proteins are post-translationally modified on their N-terminus. A common form of N-terminal modification is N-terminal methylation (Nt-methylation) by N-terminal methyltransferases (NTMTs). Proteins containing the consensus motif H2N-X-Pro-Lys- (where X can be Ala, Pro or Ser) after removal of the initiator methionine (iMet) can be subject to N-terminal α-amino-methylation.[10] Monomethylation may have slight effects on α-amino nitrogen nucleophilicity and basicity, whereas trimethylation (or dimethylation in case of proline) will result in abolition of nucleophilicity and a permanent positive charge on the N-terminal amino group. Although from a biochemical point of view demethylation of amines is possible, Nt-methylation is considered irreversible as no N-terminal demethylase has been described to date.[10] Histone variants CENP-A and CENP-B have been found to be Nt-methylated in vivo.[10]

Prenylcysteine

Eukaryotic proteins with C-termini that end in a CAAX motif are often subjected to a series of posttranslational modifications. The CAAX-tail processing takes place in three steps: First, a prenyl lipid anchor is attached to the cysteine through a thioester linkage. Then endoproteolysis occurs to remove the last three amino acids of the protein to expose the prenylcysteine α-COOH group. Finally, the exposed prenylcysteine group is methylated. The importance of this modification can be seen in targeted disruption of the methyltransferase for mouse CAAX proteins, where loss of isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methyltransferase resulted in mid-gestation lethality.[11]

The biological function of prenylcysteine methylation is to facilitate the targeting of CAAX proteins to membrane surfaces within cells. Prenylcysteine can be demethylated and this reverse reaction is catalyzed by isoprenylcysteine carboxyl methylesterases. CAAX box containing proteins that are prenylcysteine methylated include Ras, GTP-binding proteins, nuclear lamins and certain protein kinases. Many of these proteins participate in cell signaling, and they utilize prenylcysteine methylation to concentrate them on the cytosolic surface of the plasma membrane where they are functional.[11]

Methylations on the C-terminus can increase a protein's chemical repertoire[12] and are known to have a major effect on the functions of a protein.[1]

Protein phosphatase 2

In eukaryotic cells, phosphatases catalyze the removal of phosphate groups from tyrosine, serine and threonine phosphoproteins. The catalytic subunit of the major serine/threonine phosphatases, like Protein phosphatase 2 is covalently modified by the reversible methylation of its C-terminus to form a leucine carboxy methyl ester. Unlike CAAX motif methylation, no C-terminal processing is required to facilitate methylation. This C-terminal methylation event regulates the recruitment of regulatory proteins into complexes through the stimulation of protein–protein interactions, thus indirectly regulating the activity of the serine-threonine phosphatases complex.[13] Methylation is catalyzed by a unique protein phosphatase methyltransferase. The methyl group is removed by a specific protein phosphatase methylesterase. These two opposed enzymes make serine-threonine phosphatases methylation a dynamic process in response to stimuli.[13]

L-isoaspartyl

Damaged proteins accumulate isoaspartyl which causes protein instability, loss of biological activity and stimulation of autoimmune responses. The spontaneous age-dependent degradation of L-aspartyl residues results in the formation of a succinimidyl intermediate, a succinimide radical. This is spontaneously hydrolyzed either back to L-aspartyl or, in a more favorable reaction, to abnormal L-isoaspartyl. A methyltransferase dependent pathway exists for the conversion of L-isoaspartyl back to L-aspartyl. To prevent the accumulation of L-isoaspartyl, this residue is methylated by the protein L-isoaspartyl methyltransferase, which catalyzes the formation of a methyl ester, which in turn is converted back to a succinimidyl intermediate.[14] Loss and gain of function mutations have unmasked the biological importance of the L-isoaspartyl O-methyltransferase in age-related processes: Mice lacking the enzyme die young of fatal epilepsy, whereas flies engineered to over-express it have an increase in life span of over 30%.[14]

Physical effects

A common theme with methylated proteins, as with phosphorylated proteins, is the role this modification plays in the regulation of protein–protein interactions. The arginine methylation of proteins can either inhibit or promote protein–protein interactions depending on the type of methylation. The asymmetric dimethylation of arginine residues in close proximity to proline-rich motifs can inhibit the binding to SH3 domains.[15] The opposite effect is seen with interactions between the survival of motor neurons protein and the snRNP proteins SmD1, SmD3 and SmB/B', where binding is promoted by symmetric dimethylation of arginine residues in the snRNP proteins.[16]

A well-characterized example of a methylation dependent protein–protein interaction is related to the selective methylation of lysine 9, by SUV39H1 on the N-terminal tail of the histone H3.[9] Di- and tri-methylation of this lysine residue facilitates the binding of heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1). Because HP1 and Suv39h1 interact, it is thought the binding of HP1 to histone H3 is maintained and even allowed that to spread along the chromatin. The HP1 protein harbors a chromodomain which is responsible for the methyl-dependent interaction between it and lysine 9 of histone H3. It is likely that additional chromodomain-containing proteins will bind the same site as HP1, and to other lysine methylated positions on histones H3 and Histone H4.[13]

C-terminal protein methylation regulates the assembly of protein phosphatase. Methylation of the protein phosphatase 2A catalytic subunit enhances the binding of the regulatory B subunit and facilitates holoenzyme assembly.[13]

References

- Schubert, H.; Blumenthal, R.; Cheng, X. (2007). "1 Protein methyltransferases: Their distribution among the five structural classes of adomet-dependent methyltransferases 1". The Enzymes. 24: 3–22. doi:10.1016/S1874-6047(06)80003-X. ISBN 9780121227258. PMID 26718035.

- Walsh, Christopher (2006). "Chapter 5 – Protein Methylation" (PDF). Posttranslational modification of proteins: expanding nature's inventory. Roberts and Co. Publishers. ISBN 0-9747077-3-2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-12-29.

- Grewal, S. I.; Rice, J. C. (2004). "Regulation of heterochromatin by histone methylation and small RNAs". Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 16 (3): 230–238. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2004.04.002. PMID 15145346.

- Nakayama, J. -I.; Rice, J. C.; Strahl, B. D.; Allis, C. D.; Grewal, S. I. (2001). "Role of Histone H3 Lysine 9 Methylation in Epigenetic Control of Heterochromatin Assembly". Science. 292 (5514): 110–113. Bibcode:2001Sci...292..110N. doi:10.1126/science.1060118. PMID 11283354. S2CID 16975534.

- Blanc, Roméo S.; Richard, Stéphane (2017). "Arginine Methylation: The Coming of Age". Molecular Cell. 65 (1): 8–24. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2016.11.003. PMID 28061334.

- McBride, A.; Silver, P. (2001). "State of the Arg: Protein Methylation at Arginine Comes of Age". Cell. 106 (1): 5–8. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00423-8. PMID 11461695. S2CID 17755108.

- Bedford, Mark T.; Clarke, Steven G. (2009). "Protein Arginine Methylation in Mammals: Who, What, and Why". Molecular Cell. 33 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.molcel.2008.12.013. PMC 3372459. PMID 19150423.

- Wang, Yu-Chieh; Peterson, Suzanne E.; Loring, Jeanne F. (2013). "Protein post-translational modifications and regulation of pluripotency in human stem cells". Cell Research. 24 (2): 143–160. doi:10.1038/cr.2013.151. PMC 3915910. PMID 24217768.

- Kouzarides, T (2002). "Histone methylation in transcriptional control". Current Opinion in Genetics & Development. 12 (2): 198–209. doi:10.1016/S0959-437X(02)00287-3. PMID 11893494.

- Varland, Sylvia; Osberg, Camilla; Arnesen, Thomas (2015). "N-terminal modifications of cellular proteins: The enzymes involved, their substrate specificities and biological effects". Proteomics. 15 (14): 2385–2401. doi:10.1002/pmic.201400619. PMC 4692089. PMID 25914051.

- Bergo, M (2000). "Isoprenylcysteine Carboxyl Methyltransferase Deficiency in Mice". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 276 (8): 5841–5845. doi:10.1074/jbc.c000831200. PMID 11121396.

- Clarke, S (1993). "Protein methylation". Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 5 (6): 977–83. doi:10.1016/0955-0674(93)90080-A. PMID 8129951.

- Tolstykh, T (2000). "Carboxyl methylation regulates phosphoprotein phosphatase 2A by controlling the association of regulatory B subunits". The EMBO Journal. 19 (21): 5682–5691. doi:10.1093/emboj/19.21.5682. PMC 305779. PMID 11060019.

- Clarke, S (2003). "Aging as war between chemical and biochemical processes: Protein methylation and the recognition of age-damaged proteins for repair". Ageing Research Reviews. 2 (3): 263–285. doi:10.1016/S1568-1637(03)00011-4. PMID 12726775. S2CID 18135051.

- Bedford, M (2000). "Arginine Methylation Inhibits the Binding of Proline-rich Ligands to Src Homology 3, but Not WW, Domains". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (21): 16030–16036. doi:10.1074/jbc.m909368199. PMID 10748127.

- Friesen, W.; Massenet, S.; Paushkin, S.; Wyce, A.; Dreyfuss, G. (2001). "SMN, the Product of the Spinal Muscular Atrophy Gene, Binds Preferentially to Dimethylarginine-Containing Protein Targets". Molecular Cell. 7 (5): 1111–1117. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00244-1. PMID 11389857.