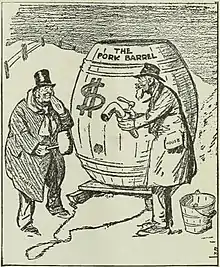

Pork barrel

Pork barrel is a metaphor for the appropriation of government spending for localized projects secured solely or primarily to bring money to a representative's district. The usage originated in American English.[1] Scholars use it as a technical term regarding legislative control of local appropriations.[2][3] In election campaigns, the term is used in derogatory fashion to attack opponents. One of the most explicit definitions of the “pork barrel” is given by Sharma (2017):[4] “The term “pork‐barrel politics” refers to instances in which ruling parties channel public money to particular constituencies based on political considerations, at the expense of broader public interests”.

Typically, "pork" involves funding for government programs whose economic or service benefits are concentrated in a particular area but whose costs are spread among all taxpayers. Public works projects, certain national defense spending projects, and agricultural subsidies are the most commonly cited examples.

Citizens Against Government Waste[5] outlines seven criteria by which spending can be classified as "pork":

- Requested by only one chamber of Congress

- Not specifically authorized

- Not competitively awarded

- Not requested by the President

- Greatly exceeds the President's budget request or the previous year's funding

- Not the subject of Congressional hearings

- Serves only a local or special interest.

History and etymology

The term pork barrel politics usually refers to spending which is intended to benefit constituents of a politician in return for their political support, either in the form of campaign contributions or votes.[6]

In the popular 1863 story "The Children of the Public", Edward Everett Hale used the term pork barrel as a homely metaphor for any form of public spending to the citizenry.[7] However, after the American Civil War, the term came to be used in a derogatory sense. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the modern sense of the term from 1873.[8]

Pork barrel originally came from storing meat.[9] By the 1870s, references to "pork" were common in Congress, and the term was further popularized by a 1919 article by Chester Collins Maxey in the National Municipal Review, which reported on certain legislative acts known to members of Congress as "pork barrel bills". He claimed that the phrase originated in a pre-Civil War practice of giving slaves a barrel of salt pork as a reward and requiring them to compete among themselves to get their share of the handout.[10] More generally, a barrel of salt pork was a common larder item in 19th-century households, and could be used as a measure of the family's financial well-being. For example, in his 1845 novel The Chainbearer, James Fenimore Cooper wrote: "I hold a family to be in a desperate way, when the mother can see the bottom of the pork barrel."[11]

Examples

An early example of pork barrel politics in the United States was the Bonus Bill of 1817, which was introduced by Democrat John C. Calhoun to construct highways linking the Eastern and Southern United States to its Western frontier using the earnings bonus from the Second Bank of the United States. Calhoun argued for it using general welfare and post roads clauses of the United States Constitution. Although he approved of the economic development goal, President James Madison vetoed the bill as unconstitutional.

One of the most famous alleged pork-barrel projects was the Big Dig in Boston, Massachusetts. The Big Dig was a project to relocate an existing 3.5-mile (5.6 km) section of the Interstate Highway System underground. The official planning phase started in 1982; the construction work was done between 1991 and 2006; and the project concluded on December 31, 2007. It ended up costing US$14.6 billion, or over US$4 billion per mile.[12] Tip O'Neill (D-Mass), after whom one of the Big Dig tunnels was named, pushed to have the Big Dig funded by the federal government while he was the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.[13]

During the 2008 U.S. presidential campaign, the Gravina Island Bridge (also known as the "Bridge to Nowhere") in Alaska was cited as an example of pork barrel spending. The bridge, pushed for by Republican Senator Ted Stevens, was projected to cost $398 million and would connect the island's 50 residents and the Ketchikan International Airport to Revillagigedo Island and Ketchikan.[14] Former Hawaii Senator Daniel Inouye described himself as “the No. 1 earmarks guy in the U.S. Congress.”[15] Inouye regularly passed earmarks for funding in the state of Hawaii including military and transportation spending.[16]

Pork-barrel projects, which differ from earmarks, are added to the federal budget by members of the appropriation committees of United States Congress. This allows delivery of federal funds to the local district or state of the appropriation committee member, often accommodating major campaign contributors. To a certain extent, a member of Congress is judged by their ability to deliver funds to their constituents. The Chairman and the ranking member of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations are in a position to deliver significant benefits to their states. Researchers Anthony Fowler and Andrew B. Hall claim that this still does not account for the high reelection rates of incumbent representatives in American legislatures.[17]

The Madrid–Seville high-speed line was a noted example of pork barrel politics in Spain. Pasqual Maragall revealed details of an unwritten agreement between him and Felipe González, the prime minister at the time who was from Seville. The agreement was that Barcelona would receive the 1992 Summer Olympics and Seville would receive the high-speed railway line (which opened in 1992).[18] This was in spite of position of the Madrid–Barcelona high-speed rail line as Spain's most profitable high-speed line.[19] Barcelona received its AVE connection in 2008, though with many advantages that the line to Seville does not have, e.g. full-speed bypasses LAV Madrid – Sevilla and LAV Madrid – Zaragoza – Barcelona: the decision to construct the line to Seville was only taken in 1986 and construction was rushed, so that the line would be ready for the Seville Expo '92.

Use of the term outside the United States

In other countries, the practice is often called patronage, but this word does not always imply corrupt or undesirable conduct.

Australia

"Pork barrel" is frequently used in Australian politics,[20][21] where marginal seats are often accused of receiving more funding than safe seats or, in the case of the 2010 election in negotiations with key independents, as well as in the 2019 election.

Central and Eastern Europe

Romanians speak of pomeni electorale (literally, "electoral alms"), while the Polish kiełbasa wyborcza means literally "election sausage". In Serbian, podela kolača ("cutting the cake") refers to post-electoral distribution of state-funded positions for the loyal members of the winning party. The Czech předvolební guláš ("pre-election goulash") has similar meaning, referring to free dishes of goulash served to potential voters during election campaign meetings targeted at lower social classes; metaphorically, it stands for any populistic political decisions that are taken before the elections with the aim of obtaining more votes. The process of diverting budget funds in favor of a project in a particular constituency is called porcování medvěda ("portioning of the bear") in Czech usage.[22]

India

In India, the term "pork barrel politics" has been employed to depict the pattern of distribution of discretionary grants by the national government (see for example Biswas et al. 2010;[23] Rodden and Wilkinson 2004;[24] Sharma, 2017.[25] However (Sharma, 2017) is most explicit in drawing the parallel between the tactical distribution of grants in India and the notion of pork barrel politics. Chanchal Kumar Sharma demonstrates that the incentives of the Prime Minister's party under a coalition system create a universalisation effect which means "giving something to everyone". Thus, the states governed by non-affiliated parties do not suffer as much as in the dominant party era. In fact, a coalition party system limits opportunities to reward party loyalty (see Sharma 2017).

Ireland

The term parish pump politics is more commonly used in Ireland although Independent TD Shane Ross did refer to Pork Barrel politics at a press conference for the Independent Alliance in the run up to the 2016 general election, saying that the Alliance was "not interested in pork barrel politics".[26] Despite being appointed Minister for Transport, Tourism and Sport in the 32nd Dáil he went on to prioritise the reopening of a police station in his own constituency which was eventually delivered on the eve of the election of new Taoiseach Leo Varadkar in June 2017.[27]

German-speaking countries

The German language differentiates between campaign goodies (Wahlgeschenke, literally "election gifts") to occur around election dates and parish-pump politics (Kirchturmpolitik, literally "church tower politics") for concentrating funding and reliefs to the home constituency of a politician. While the former is a technical term (neutral or slightly derogatory) the latter is always derogatory meaning that the scope of actions is limited to an area where the steeple of the politician's village can still be seen. In Switzerland the wording of provincial thinking (Kantönligeist, literally "cantonal mind") may cover these actions as well and it is understood as a synonym in Germany and Austria.

Philippines

In the Philippines, the term "pork barrel" is used to mean funds allocated to the members of the Philippine House of Representatives and the Philippine Senate to spend as they see fit without going through the normal budgetary process or through the Executive Branch. It can be used for both "hard" projects, such as buildings and roads, and "soft" projects, such as scholarships and medical expenses. The first pork barrel fund was introduced in 1922 with the passage of the first Public Works Act (Act No 3044). This pork barrel system was technically stopped by President Ferdinand Marcos during his dictatorship by abolishing Congress. It was reintroduced to the system after the restoration of the Congress in 1987. The program has had different names over the years, including the Countryside Development Fund, Congressional Initiative Fund, and currently the Priority Development Assistance Fund. Since 2006, the PDAF was ₱70.0 M for each Representative and ₱200.0 M for each Senator.

During the presidency of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, PDAF became the biggest source of corruption among the legislators.[28] Kickbacks were common and became syndicated—using pre-identified project implementers including government agencies, contractors and bogus non-profit corporations as well as the government's Commission on Audit.[29]

In August 2013, outrage over the ₱10 billion Priority Development Assistance Fund scam, involving Janet Lim-Napoles and numerous Senators and Representatives, led to widespread calls for abolition of the PDAF system.[30] The so-called Million People March which occurred on August 26, 2013, National Heroes' Day in the Philippines, called for the end of "pork barrel" and was joined by simultaneous protests nationwide and by the Filipino diaspora around the world.[31]

Petitioners have challenged the constitutionality of the PDAF before the high court following reports of its widespread and systematic misuse by some members of Congress in cahoots with private individuals. Three incumbent senators and several former members of the House of Representatives have been named respondents in a plunder complaint filed with the Office of the Ombudsman in connection with the alleged ₱10 billion pork barrel scam. Public outrage over the anomaly has resulted in the largest protest gathering under the three-year-old Aquino administration.[32]

On November 19, 2013, the Supreme Court declared the controversial Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF), or more commonly known as the pork barrel, as unconstitutional. In a briefing, the high court declared the PDAF Article in 2013 General Approriations Act and all similar provisions on the pork barrel system as illegal because it "allowed legislators to wield, in varying gradiations, non-oversight, post-enactment authority in vital areas of budget executions (thus violating) the principle of separation of powers".[32]

Nordic countries

Similar expressions, meaning "election meat", are used in Danish (valgflæsk), Swedish (valfläsk) and Norwegian (valgflesk), where they mean promises made before an election, often by a politician who has little intention of fulfilling them.[33] The Finnish political jargon uses siltarumpupolitiikka (culvert politics) in reference to national politicians concentrating on small local matters, such as construction of roads and other public works at politician's home municipality. In Iceland, the term kjördæmapot refers to the practice of funneling public funds to key voting demographics in marginal constituencies.

United Kingdom

The term is rarely used in British English, although similar terms exist: election sweetener, tax sweetener, or just sweetener, which refers to the practise of a chancellor of the exchequer leaving room in their fiscal program to announce a big tax cut or spending boost in the budget immediately prior to an election, usually targeting a key voting demographic (such as the elderly) or benefitting marginal constituencies.[34] The term "pork barrel" was, however, used in August 2013 by the Campaign for Better Transport in their criticism of Danny Alexander MP's involvement in securing funding for the A6 Manchester Airport Relief Road which passed through a marginal Liberal Democrat constituency.[35] It was also used by Pete Wishart in the House of Commons on 26 June 2017 in reference to the deal between the Conservative Party and the Democratic Unionist Party to keep the former in power.[36] In February 2019 it was used by shadow chancellor John McDonnell to criticise Theresa May's rumoured attempts to persuade Labour MPs to vote for her Brexit deal. [37]

See also

- Advocacy group

- All politics is local

- Citizens Against Government Waste

- Client politics

- Clientelism

- Corporate welfare

- Earmark (politics)

- Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006

- Golden Fleece Award

- Government waste

- Lobbying

- Money loop

- People's Initiative Against Pork Barrel

- Porkbusters

- Spoils system

References

- Drudge, Michael W. Special Correspondent (1 August 2008). ""Pork Barrel" Spending Emerging as Presidential Campaign Issue". America.gov. United States Department of State. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- Bickers, Kenneth N.; Stein, Robert M. (2008). "The Congressional Pork Barrel in a Republican Era". The Journal of Politics. 62 (4): 1070–1086. doi:10.1111/0022-3816.00046. JSTOR 2647865. S2CID 154556676.

- Shepsle, Kenneth A.; Weingast, Barry R. (1981). "Political Preferences for the Pork Barrel: A Generalization". American Journal of Political Science. 25 (1): 96–111. doi:10.2307/2110914. JSTOR 2110914.

- Sharma, Chanchal Kumar (2017-01-02). "A situational theory of pork-barrel politics: The shifting logic of discretionary allocations in India" (PDF). India Review. 16 (1): 14–41. doi:10.1080/14736489.2017.1279922. hdl:10419/156103. ISSN 1473-6489. S2CID 55173537.

- "Citizens Against Government Waste". Cagw.org. 2006. Archived from the original on July 14, 2008.

- Sharma, Chanchal Kumar (2017-01-02). "A situational theory of pork-barrel politics: The shifting logic of discretionary allocations in India" (PDF). India Review. 16 (1): 14–41. doi:10.1080/14736489.2017.1279922. hdl:10419/156103. ISSN 1473-6489. S2CID 55173537.

- The story first appeared in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, Jan. 24 and Jan. 31, 1863. Hale, Edward Everett (1910). "The Children of the Public". The Man without a Country and Other Tales. Macmillan: 97–175. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Oxford English Dictionary, pork barrel, draft revision June 2008. Retrieved October 22, 2008.

- "Dictionary and Thesaurus | Merriam-Webster". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- Maxey, Chester Collins (1919). "A Little History of Pork". National Municipal Review. 8 (10): 691–705. doi:10.1002/ncr.4110081006.

- Quoted in: Volo, James M.; Volo, Dorothy Denneen (2004). The Antebellum Period. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-313-32518-2.

- Klein, Rick (August 6, 2006). "Big Dig failures threaten federal funding". The Boston Globe.

- Rimer, Sara (30 December 2009). "In Boston, Where Change Is in the Winter Air". New York Times. Retrieved 17 November 2010.

- $315 million bridge to nowhere (PDF). Taxpayers for Common Sense. February 9, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 25, 2008.

- Brown, Emma; Post, The Washington. "Daniel Inouye was war hero, Senate deal maker, 'No. 1 earmarks guy'". The Bangor Daily News. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- "Daniel K. Inouye: Campaign Finance/Money – Other Data – Earmarks 2010". www.opensecrets.org. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- Fowler, Anthony; Hall, Andrew B. (December 2015). "Congressional seniority and pork: a pig fat myth?". European Journal of Political Economy. 40 (A): 42–56. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2015.07.006.

- Iglesias, Natalia (18 November 2007). "Maragall revela que acordó con González que el AVE llegara primero a Sevilla". El País.

- "Solo 11 de 179 rutas de tren en España cubren gastos operativos". La Preferente.

- Taylor, Lenore (3 June 2008). "The Australian: PM rolls out his own pork barrel". The Australian. News Corp Australia. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- Pearlman, Jonathan; Coorey, Phillip (16 November 2007). "Vaile in last-ditch pork barrel". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Porcování medvěda zvítězilo nad ideály". Euro.cz. Retrieved 14 August 2010.

- Biswas, Rongili; Marjit, Sugata; Marimoutou, Velayoudom (2010). "Fiscal Federalism, State Lobbying and Discretionary Finance: Evidence from India". Economics & Politics. 22: 68–91. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0343.2009.00363.x. S2CID 59387644.

- Rodden and S. Wilkinson, 2005. The Shifting Political Economy of Redistribution in the Indian Federation

- Sharma, Chanchal Kumar (2017). "A situational theory of pork-barrel politics: The shifting logic of discretionary allocations in India" (PDF). India Review. 16: 14–41. doi:10.1080/14736489.2017.1279922. hdl:10419/156103. S2CID 55173537.

- Kelly, Fiach (February 25, 2016). "Independents not interested in 'pork barrel' politics, says Shane Ross". The Irish Times.

- "Stepaside Garda station to re-open, fulfilling key Shane Ross demand". Irish Times.

- Cabacungan, Gil (22 August 2013). "Arroyo chose who, how much PDAF to give". Inquirer.net. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- Cabacungan, Gil C. "Arroyo chose who, how much PDAF to give". newsinfo.inquirer.net. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- "PDAF wins elections, favors political parties". Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- Francisco, Rosemarie (26 August 2013). "Tens of thousands of Filipinos protest "pork barrel" funds". Reuters.com. Retrieved 28 August 2013.

- Merueñas, Mark (19 November 2013). "Supreme Court declares PDAF unconstitutional". GMA News.

- Nationalencyklopedin, NE Nationalencyklopedin AB. Article Valfläsk

- Thornton, Philip (24 February 2005). "Brown warned on pre-election tax 'sweeteners'". The Independent. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Treasury minister's role in road funding 'in danger of looking like pork barrel politics' (blog)". bettertransport.org.uk. Campaign for Better Transport. 12 August 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- Millar, Joey (27 June 2017). "'It's almost laughable!' Greedy SNP put in place after saying DUP deal UNFAIR for Scotland". Retrieved 7 August 2018.

- McDonnell, John (2 February 2019). "McDonnell accuses PM of 'pork-barrel' politics with Brexit 'bribery'". Retrieved 2 February 2019.