Plume hunting

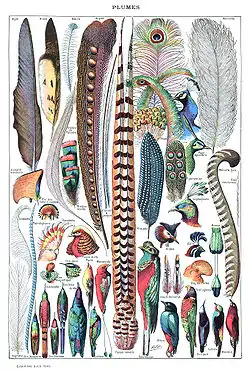

Plume hunting is the hunting of wild birds to harvest their feathers, especially the more decorative plumes which were sold for use as ornamentation, such as aigrettes in millinery. The movement against the plume trade in the United Kingdom was led by Etta Lemon and other women and led to the establishment of the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. The plume trade was at its height in the late 19th and was brought to an end in the early 20th century.

By the late 19th century, plume hunters had nearly wiped out the snowy egret population of the United States. Flamingoes, roseate spoonbills, great egrets and peafowl have also been targeted by plume hunters. The Empress of Germany's bird of paradise was also a popular target of plume hunters.

Victorian era fashion included large hats with wide brims decorated in elaborate creations of silk flowers, ribbons, and exotic plumes. Hats sometimes included entire exotic birds that had been stuffed. Plumage often came from birds in the Florida everglades, some of which were nearly extinguished by overhunting. By 1899, early environmentalists such as Adeline Knapp were engaged in efforts to curtail the hunting for plumes. By 1900, more than five million birds were being killed every year, including 95 percent of Florida's shore birds.[1]

In Hawaii, Kāhili are feather standards worn by the chiefly class. Kanaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians) did not hunt and kill the birds. Native American war bonnets and various feather headdresses also feature feathers.

Hunt for plumes

At the turn of the 20th century, thousands of birds were being killed in order to provide feathers to decorate women's hats. The fashion craze, which began in the 1870s, became so widespread that by 1886 birds were being killed for the millinery trade at a rate of five million a year; many species faced extinction as a result.[2] In Florida, plume birds were first driven away from the most populated areas in the northern part of the state, and forced to nest further south. Rookeries concentrated in and around the Everglades area, which had abundant food and seasonal dry periods, ideal for nesting birds. By the late 1880s, there were no longer any large numbers of plume birds within reach of Florida's most settled cities.[3]

The most popular plumes came from various species of egret, known as "little snowies" for their snowy-white feathers; even more prized were the "nuptial plumes", grown during the mating season and displayed by birds during courtship.[4] So-called "osprey" plumes, actually egret plumes, were used as part of British army uniforms until they were discontinued in 1889.[5] Poachers often entered the densely populated rookeries, where they would shoot and then pluck the roosting birds clean, leaving their carcasses to rot. Unprotected eggs became easy prey for predators, as were newly hatched birds, who also starved or died from exposure. One ex-poacher would later write of the practice, "The heads and necks of the young birds were hanging out of the nests by the hundreds. I am done with bird hunting forever!"[6]

Egrets, including the great egret, were decimated in the past by plume hunters, but numbers recovered when given protection in the 20th century.[7]

In 1886, 5 million birds were estimated to be killed for their feathers.[8] They were shot usually in the spring, when their feathers were colored for mating and nesting. The plumes, or aigrettes, as they were called in the millinery business, sold for $32 an ounce in 1915 — which was also the price of gold then.[9] Millinery was a $17 million a year industry[10] that motivated plume harvesters to lay in wait at the nests of egrets and other birds during the nesting season, shoot the parents with small-bore rifles, and leave the chicks to starve.[9] Plumes from Everglades water birds could be found in Havana, New York City, London, and Paris. Hunters could collect plumes from a hundred birds on a good day.[11]

Guy Bradley

In 1885, 15-year-old Guy Bradley and his older brother Louis served as scouts for noted French plume hunter Jean Chevalier on his trip to the Everglades.[12] Accompanied by their friend Charlie Pierce, the men set sail on Pierce's craft, the Bonton, ending their journey in Key West. At the time, plume feathers—selling for more than $20 an ounce ($501 in 2011)—were reportedly more valuable per weight than gold.[13] On their expedition, which lasted several weeks, the young men and Chevalier's party killed 1,397 birds of 36 species.[14] Bradley eventually became a warden protecting birds from the plume hunting trade.

Conservation

In Florida, in an effort to control plume hunting, the American Ornithologists Union and the National Association of Audubon Societies (now the National Audubon Society) persuaded the Florida State Legislature to pass a model non-game bird protection law in 1901. These organizations then employed wardens to protect rookeries, in effect establishing colonial bird sanctuaries.

Such public concern, combined with the conservation-minded President Theodore Roosevelt, led to his executive order of President on March 14, 1903, establishing Pelican Island as the first national wildlife refuge in the United States to protect egrets and other birds from extinction by plume hunters. This resulted in the initial federal land specifically set aside for a non-marketable form of wildlife (the brown pelican) when 3-acre (12,000 m2) Pelican Island was proclaimed a Federal Bird Reservation in 1903. Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge is said to be the first bona fide "refuge". The first warden employed by the government at Pelican Island, Paul Kroegel, was an Audubon warden whose salary was $1 a month. Plume hunter guide turned game warden Guy Bradley was shot and killed after confronting plume hunters.[15]

Following the modest trend begun with Pelican Island, many other islands and parcels of land and water were quickly dedicated for the protection of various species of colonial nesting birds that were being destroyed for their plumes and other feathers. Such refuge areas included Breton National Wildlife Refuge in Breton, Louisiana (1904), Passage Key National Wildlife Refuge in Passage Key, Florida (1905), Shell Keys National Wildlife Refuge in Shell Keys, Louisiana (1907), and Key West National Wildlife Refuge in Key West, Florida (1908).

Bird City

Bird City is a private wildfowl refuge or bird sanctuary located on Avery Island in coastal Iberia Parish, Louisiana, founded by Tabasco sauce heir and conservationist Edward Avery McIlhenny, whose family owned Avery Island. McIlhenny established the refuge around 1895 on his own personal tract of the 2,200-acre (8.9 km2) island, a 250-acre (1.0 km2) estate known eventually as Jungle Gardens because of its lush tropical flora in response to late 19th century plume hunters nearly wiping out the snowy egret population of the United States while in pursuit of the bird's delicate feathers.

McIlhenny searched the Gulf Coast and located several surviving egrets, which he took back to his estate on Avery Island. There he turned the birds loose in a type of aviary he called a "flying cage," where the birds soon adapted to their new surroundings. In the fall McIlhenny set the birds loose to migrate south for the winter.

As he hoped, the birds returned to Avery Island in the spring, bringing with them even more snowy egrets. This pattern continued until, by 1911, the refuge served as the summer nesting ground for an estimated 100,000 egrets.[16]

Because of its early founding and example to others, Theodore Roosevelt, father of American conservationism, once referred to Bird City as "the most noteworthy reserve in the country."[17]

Today, snowy egrets continue to return to Bird City each spring to nest until resuming their migration in the fall.

Empress of Germany's bird of paradise and captive breeding

The Empress of Germany's bird of paradise was one of the most heavily hunted birds of paradise in the plume-hunting era, and was the first bird of paradise to breed in captivity. It was bred and observed by Prince R.S. Dharmakumarsinhji of India in 1940.

References

- "Everglades National Park". PBS. Retrieved November 7, 2011.

- McIver, p. xiii.

- McIver, p. 46.

- Shearer, p. 36.

- "In the Queen's name". Bird Notes and News. 2 (1): 20. 1906.

- Huffstodt, pp. 42–43.

- Hammerson, Geoffrey A., Connecticut Wildlife: Biodiversity, Natural History, and Conservation, University Press of New England: Hanover, New Hampshire, and London, 2004, ISBN 1-58465-369-8, Chapter 20 "Birds"

- Grunwald, p. 120.

- McCally, p. 117.

- Douglas, p. 310.

- McCally, pp. 117–118.

- Tebeau, p. 75.

- McIver, p. 16.

- McIver, p. 29.

- "Everglades Biographies: Guy Bradley". Everglades Digital Library. Retrieved on July 1, 2010.

- Edward Avery McIlhenny, Bird City (Boston: Christopher Publishing House, 1935), passim.

- Theodore, Roosevelt, "Bird Reserves at the Mouth of the Mississippi River," A Book-Lover’s Holidays in the Open (1916), n.p.

Sources

- Douglas, Marjory (1947). The Everglades: River of Grass. 60th Anniversary Edition, Pineapple Press (2007). ISBN 978-1-56164-394-3

- Grunwald, Michael. The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, 2006. ISBN 0-7432-5105-9.

- Huffstodt, Jim. Everglades Lawmen: True Stories of Danger and Adventure in the Glades. Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press, 2000. ISBN 1-56164-192-8.

- McCally, David (1999). The Everglades: An Environmental History. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2302-5.

- McIver, Stuart B. Death in the Everglades: The Murder of Guy Bradley, America's First Martyr to Environmentalism. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2003. ISBN 0-8130-2671-7.

- Shearer, Victoria. It Happened in the Florida Keys. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-7627-4091-8.

- Tebeau, Charlton W. They Lived in the Park: The Story of Man in the Everglades National Park. Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Press, 1963.

Further reading

- Boase, Tessa (2018). Mrs Pankhurst's Purple Feather. Aurum. ISBN 978-1781316542.

- Supuma, Miriam (2018). Endemic birds in Papua New Guinea's montane forests: human use and conservation (phd thesis). James Cook University. doi:10.25903/5d0194ca93995.