Plasmodium cynomolgi

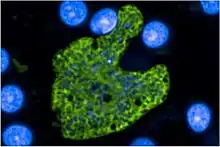

Plasmodium cynomolgi is an apicomplexan parasite that infects mosquitoes and Asian Old World monkeys. This species has been used as a model for human Plasmodium vivax because Plasmodium cynomolgi shares the same life cycle and some important biological features with P. vivax.[1]

| Plasmodium cynomolgi | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| (unranked): | Diaphoretickes |

| Clade: | TSAR |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Infrakingdom: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Apicomplexa |

| Class: | Aconoidasida |

| Order: | Haemospororida |

| Family: | Plasmodiidae |

| Genus: | Plasmodium |

| Species: | P. cynomolgi |

| Binomial name | |

| Plasmodium cynomolgi (Mayer, 1907) | |

Life cycle

The life cycle of P. cynomolgi resembles that of other Plasmodium species, particularly the related human parasite Plasmodium vivax.[2] Like other Plasmodium species, P. cynomolgi infects both an insect host and a vertebrate (generally Old World monkeys). The parasite is transmitted when the mosquito host takes a blood meal from the vertebrate host. During the feeding, motile parasites called sporozoites are injected from the mosquito salivary gland into the host tissue. These sporozoites move into the bloodstream and infect cells in the host liver, where they grow and divide over the course of approximately one week.[3] At this point, the parasitized liver cells rupture, releasing thousands of parasite daughter cells, called merozoites, which either move into the bloodstream to infect red blood cells, or remain in the liver to reinfect liver cells. Those that reinfect liver cells form a quiescent stage called a hypnozoite, which can remain dormant in the liver cell for months or years before reactivating.[3] The merozoites that enter the bloodstream infect red blood cells, where they grow and replicate. After approximately 48 hours, the infected red blood cell bursts, allowing the daughter merozoites to infect new red blood cells. This cycle can continue indefinitely. Occasionally, after infection of a red blood cell, the parasite develops into one of two distinct sexual forms called male and female gametocytes (also micro and macrogametocytes respectively). If a mosquito takes a blood meal containing a gametocyte of each sex, the two sexual stages merge and form a zygote.[3] The zygote develops into a motile stage called the ookinete which penetrates the wall of the mosquito gut and forms a stationary oocyst. The oocyst develops over about 11 days, then begins to release thousands of sporozoites into the mosquito's hemolymph. The sporozoites move through the hemolymph and infect the mosquito salivary glands, where they will again be injected into a mammalian host when the mosquito takes a blood meal.[3]

Description

P. cynomolgi closely resembles the human parasite P. vivax throughout its life cycle. Similar to P. vivax, P. cynomolgi infection changes the red blood cell membrane structure, causing surface perturbations that appear as pink dots (called Schüffner's dots) when stained with Giemsa.[3]

Ecology and distribution

P. cynomolgi is found throughout Southeast Asia where it naturally infects a variety of macaque monkeys, including Macaca cyclopis, Macaca fascicularis, Macaca mulatta, Macaca nemestrina, Macaca radiata, Macaca sinica, Trachypithecus cristatus, and Semnopithecus entellus.[3][4] The effect of infection on primate hosts has primarily been studied in rhesus monkeys, where P. cynomolgi generally causes mild and self-limiting illness.[3] Monkeys can suffer anemia and thrombocytopenia as well as occasional kidney inflammation, however all generally resolve without treatment.[3] The exception to this is in pregnant monkeys, where P. cynomolgi infection can be severe, resulting in death of the mother and fetus without antimalarial treatment.[3]

Infection of humans with P. cynomolgi is exceedingly rare. However, occasional zoonotic infections have been described. In addition to a few naturally occurring cases, human infection by P. cynomolgi has been verified in laboratories both by experimental infection of human volunteers and by laboratory accidents resulting in human infection.[4][5] Transmission of P. cynomolgi from human to human by a mosquito vector has also been shown in laboratory experiments, although it appears to occur rarely if at all in the environment.[4]

P. cynomolgi also infects a broad variety of Anopheles mosquitoes; the effect of infection on these mosquitoes is not known.[3]

Taxonomy and evolution

P. cynomolgi is in the genus Plasmodium, which contains all Apicomplexan parasites that undergo asexual reproduction through schizogony and digest red blood cell hemoglobin to produce the crystalline pigment hemozoin. Within Plasmodium, P. cynomolgi is in the subgenus Plasmodium, containing all species of Plasmodium that infect primates (except for some that infect the Great Apes, which are in the subgenus Laverania).

Evolutionarily, P. cynomolgi is most closely related to the other Plasmodium species that infect monkeys, as well as P. vivax which infects humans. Evolutionary relationships among Plasmodium species have been inferred from ribosomal RNA sequencing, and are summarized in the cladogram below:[6]

|

Plasmodium subgenus Vinckeia (infects rodents) | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Research

P. cynomolgi is the second-most studied malaria parasite of non-human primates after Plasmodium knowlesi, primarily due to its similarity to the human parasite P. vivax.[2] In particular, P. cynomolgi is used as a model for hypnozoite biology as it (along with P. vivax) is one of the few Plasmodium species known to have this lifecycle stage.[2] P. cynomolgi can infect a variety of monkey species and can be transmitted by several common laboratory-grown mosquitoes.[7][2] Due to this, P. cynomolgi has been used in research on a broad variety of malaria topics including hypnozoite biology, host immune responses to infection, and to test the efficacy of antimalarial drugs and vaccines.[2]

History

P. cynomolgi was first observed in 1905 in the blood of the long-tailed macaque.[2]

References

- "Plasmodium cynomolgi - Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute". www.sanger.ac.uk. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- Martinelli A, Culleton R (2018). "Non-human primate malaria parasites: out of the forest and into the laboratory". Parasitology. 145: 41–54. doi:10.1017/S0031182016001335.

- Galinski MR, Barnwell JW (2012). "Nonhuman primate models for human malaria research". Nonhuman Primates in Biomedical Research: Diseases. Elsevier. pp. 299–324.

- Cormier LA. "Ethics: Human Experimentation". The ten-thousand year fever: rethinking human and wild primate malarias. Routledge. pp. 127–130. ISBN 9781598744835.

- Baird JK (2009). "Malaria zoonoses". Travel Medicine nad Infectious Disease. 7 (5): 269–277. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2009.06.004. PMID 19747661.

- Leclerc MC, Hugot JP, Durand P, Renaud F (2004). "Evolutionary relationships between 15 Plasmodium species from New and Old World primates (including humans): an 18S rDNA cladistic analysis". Parasitology. 129 (6): 677–684. doi:10.1017/s0031182004006146. PMID 15648690.

- Collins WE, Warren M, Galland GG (1999). "Studies on Infections with the Berok strain of Plasmodium cynomolgi in monkeys and mosquitoes". The Journal of Parasitology. 85 (2): 268–272. doi:10.2307/3285631.