Pierre-Paul Pecquet du Bellet

Pierre-Paul Pecquet du Bellet (or du Bellay) (April 6, 1816 – January 21, 1884) was an American attorney, author, and unofficial diplomatic agent of the Confederate States of America in France.

Pierre-Paul Pecquet du Bellet | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Pierre Paul de Pommayrac | |

| Born | April 16, 1816 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | January 21, 1884 (aged 67) Paris, France |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Unofficial Diplomatic Agent of the Confederate States of America |

Early life, Family and Career

Pierre-Paul Pecquet du Bellet is first mentioned as being born in New Orleans on April 6, 1816. His father, Dr. Joseph du Bellet, had left France in 1793 and moved to Saint-Domingue following the French Revolution.[1]

He later moved to New Orleans following the Haitian Revolution.[2] He eliminated the aristocratic "du Bellet" from his name in New Orleans and became known simply as Joseph Pecquet. He married a widow and purchased a plantation in Louisiana where his two sons, Pierre-Paul and Pierre-François, were born. Both brothers later married two sisters. Pierre-Paul Pecquet du Bellet married Sarah Anne Elisabeth Moncure, born in Richmond in September 1826 and died in Paris in December 1914.[3]

Pierre-Paul is registered as living in New Orleans at 70 Royal Street in the 1827 and 1842 New Orleans Directory and Registry.[4] The 1842 registry describes him as a "Student-at-Law". Cohen's New Orleans Directory for the years 1851-1855 lists him as an attorney with offices at 45 Camp Street and living at 42 Rampart Street.[5] He later moved to Paris around the year 1856 and stated, in an 1871 article in "Le Salut des Peuples Européens", that he had been living in France for the last 15 years.[6] His brother, Pierre-François, later became a plantation owner in Pointe Coupee Parish, Louisiana.[7]

Confederate Agent in Europe

Pierre-Paul Pecquet du Bellet, being a Confederate sympathizer living in Paris and fluent in the French language, immediately assumed the role of chief-representative of the Confederacy in France. In his own words, he stated that he was "taking up the pen, not being able to take up the sword".[8] His ultimate aim was to rally popular and political sympathy away from Abraham Lincoln's official envoy, John Bigelow, and towards that of the Confederacy. On 14 May 1861, he wrote a letter to Robert Toombs, Secretary of State of the Confederate States of America, stressing the importance of publishing articles favorable to the Confederacy in French newspapers.[9]

His first articles defending the Confederacy were written in February 1861 in the French newspaper "Le Pays" (The Country), with the assistance of the influential French journalist Adolphe Granier de Cassagnac.[10] These articles were translated and published in the New York Herald in March 1861. He continued writing articles in French in May 1861 for one of the most pro-Confederate French newspapers, Le Constitutionnel. That same year he published two small books: "La Révolution Américaine Dévoilée" (The American Revolution Revealed) and "Le Blocus Américain" (The American Blockade). In 1862 he published two monographs entitled "Lettre à l’Empereur: De la Reconnaissance des États Confédérés d’Amérique" (Letter to the Emperor: Recognizing the Confederate States of America) and "Lettre sur la Guerre Américaine" (Letter on the American War). In 1864 he published "L’Amérique du Nord: Lettre au Corps Législatif" (North America: Letter to the Legislative Corps). In an article for "Le Pays" in September 1862, du Bellet warned his readers to not believe in Lincoln, arguing that "he has deceived, he deceives, and he will deceive".[11] He warned that the North, through its Monroe Doctrine, was seeking to take over and conquer Mexico, Central America, and Canada.[12]

In a June 1861 article for "Le Pays", du Bellet argued that the Confederates were Latins worthy of French aid, contrary to Northerners who were of Anglo-Saxon ancestry. He insisted that the heart beating in the Confederate population was a French heart. Adam Gurowski, a Polish-born US citizen working in the US State Department, replied to du Bellet on June 20, 1861 stating that the Confederates were opportunists, "French in Paris and English in the London Times".[13]

Du Bellet was highly critical of Edwin de Leon, the Confederacy's unofficial propaganda agent in Europe, who disbursed important sums of money to influence journalists and newspapers to the Southern cause. Regarding De Leon's thirty-two page pamphlet entitled "La Vérité sur les Etats Confédérés d'Amérique" (The Truth on the Confederate States of America), du Bellet mocked its "peculiar style of French, which he thought a bit too Americanized for the tastes of French editors".[14]

Du Bellet met on numerous occasions in Paris with the Confederacy's official diplomatic mission to England and France, including William Lowndes Yancey, a vocal leader of the Southern secession movement and member of the Fire-Eaters, as well as Pierre Adolphe Rost, a Louisiana attorney who represented the Confederacy's interests in Spain.[15]

Aside from writing articles in political newspapers, du Bellet also served the war effort by attempting to provide arms from France to the Confederacy.[16] On 17 July 1861, he met in Paris with Rost and Caleb Huse, the Confederacy's procurement agent in Liverpool, regarding the possible acquisition of used French arms at an arsenal located in Vincennes.[17] Napoleon III's secret police was soon tipped off that agents of the Confederacy, meeting in Paris on the rue du Helder, were seeking to acquire arms.[18]

Following the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865, du Bellet published his critical "The Diplomacy of the Confederate Cabinet of Richmond and Its Agent Abroad". In this study, du Bellet argued that the Confederacy was heavily penalized by its amateurish agents abroad, including men such as Pierre Adolphe Rost, James Murray Mason, John Slidell, Samuel Barron, and Henry Hotze. He applauded his own diplomatic efforts, pointing out that he had obtained from the French-German banker Émile d'Erlanger the sum of 5 million pounds for the war effort.[19] It is important to note that d'Erlanger had married the Confederate envoy John Slidell's daughter, Marguerite Mathilde, on October 3, 1864.

The abolitionist Moncure Daniel Conway, directly related to du Bellet's spouse, stated in his 1904 autobiography that du Bellet had told the Confederate government in Richmond that "as the war would certainly end slavery, even were the South victorious", emancipation should immediately be granted to gain international recognition of the Confederate States of America.[20]

Post-war Activities and the Franco-Texan Land Company

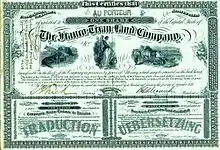

Following the war, du Bellet remained in Paris with his wife and children. In 1869, he and other French citizens invested heavily in the Memphis, El Paso and Pacific Railway by purchasing bonds being sold in France by John C. Frémont.[21] When Frémont's project eventually collapsed, du Bellet and the other investors found themselves owning 640,000 acres of Texas land which had secured their bonds.

On 12 June 1873, the Texas and Pacific Railway purchased what remained of the Memphis, El Paso and Pacific Railway while Frémont's creditors in New York attempted to sell the remaining bonds as the "Franco-Texas Land Company". The French bondholders thus owned thirteen acres of Texas land for each $100 bond they possessed, and this collective land in their possession constituted the entire capital stock of the Franco-Texan Land Company.[22] From Paris, du Bellet followed these proceedings attentively and immediately contacted an old Louisiana acquaintance, P.G.T. Beauregard, hoping that he would take over the role of president of the land company.[23] Beauregard ultimately declined the offer but the Franco-Texas Land Company would continue to exist in the decades ahead, with du Bellet's own son moving to Weatherford, Texas to supervise the management and sale of the land. Du Bellet organized for the Board of Directors to meet in Paris, agreeing to sell land in Texas at a rapid rate. Eventually du Bellet would administer a second land company, the "Société Foncière et Agricole des Etats-Unis", with his son acting as agent of both companies directly in Texas.[24]

In the spring of 1881, Pierre-Paul du Bellet was in Weatherford assisting his son with the Société. He returned to France on July 16, just before his son had purchased 251 lots of land and incorporated a new company by the name of Weatherford Water Supply Company.[25] The Société back in Paris would eventually declare bankruptcy on November 4, 1882.[26]

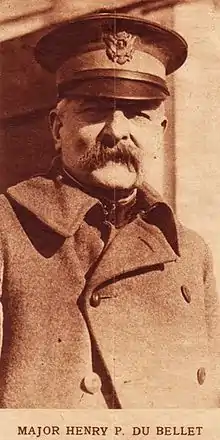

According to the Texas State Historical Association, du Bellet's son "Henry P. du Bellet, vice secretary residing in Paris, staged a coup in which the New York officers were ousted and Sam H. Milliken of Weatherford was elected president. Du Bellet then came to Texas and had a hand in the company's affairs until he too was ousted...With the gradual increase in the value of Texas land, the Franco-Texan Land Company developed into something of a bonanza for the French and American directors, who bought stock certificates for a few cents on the dollar and conspired to riddle the company's coffers. The losers were the French peasants who had invested their life savings in the Memphis, El Paso and Pacific bonds. In 1896, after years of local rivalry and dissension, the charter of the Franco-Texan Land Company expired by limitation. On request, the legislature allowed the company three additional years to liquidate its assets and conclude its business".[27]

Works

- "La Révolution Américaine Dévoilée" (The American Revolution Revealed), 1861

- "Le Blocus Américain" (The American Blockade), 1861

- "Lettre à l’Empereur: De la Reconnaissance des États Confédérés d’Amérique" (Letter to the Emperor: On the Confederate States of America's Gratitude), 1862

- "Lettre sur la Guerre Américaine" (Letter on the American War), 1862

- "L’Amérique du Nord: Lettre au Corps Législatif" (North America: Letter to the Legislative Corps), 1864

- "The Diplomacy of the Confederate Cabinet of Richmond and Its Agent Abroad", 1865

Further reading

- Jones, Howard. Blue & Gray Diplomacy: A History of Union and Confederate Foreign Relations (2010)

- Cullop, Charles P. Confederate Propaganda in Europe, 1861–1865 (1969)

- Fleche, Andre. Revolution of 1861: The American Civil War in the Age of Nationalist Conflict (2012)

References

- "PECQUET DU BELLET DE VERTON AND KARIOUK FAMILY PAPERS" (PDF).

- "PECQUET DU BELLET DE VERTON AND KARIOUK FAMILY PAPERS" (PDF).

- "La Louisiane francophone autour d'une famille".

- "The Franco-Texan Land Company".

- "The Franco-Texan Land Company".

- "The Franco-Texan Land Company".

- "PECQUET DU BELLET DE VERTON AND KARIOUK FAMILY PAPERS" (PDF).

- "CONFEDERATE HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION OF BELGIUM" (PDF).

- "PECQUET DU BELLET DE VERTON AND KARIOUK FAMILY PAPERS" (PDF).

- "French Newspaper Opinion on the American Civil War".

- "French Newspaper Opinion on the American Civil War".

- "French Newspaper Opinion on the American Civil War".

- "Les créoles louisianais défendent la cause du Sud à Paris (1861‑1865)".

- "The U.S. South and Europe: Transatlantic Relations in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries".

- "William Lowndes Yancey and the Coming of the Civil War".

- "Dancing With The Philistines: The Life and Times of Colonel Caleb Huse".

- "Dancing With The Philistines: The Life and Times of Colonel Caleb Huse".

- "Dancing With The Philistines: The Life and Times of Colonel Caleb Huse".

- "Les créoles louisianais défendent la cause du Sud à Paris (1861‑1865)".

- "Autobiography: Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway".

- "The Franco-Texan Land Company".

- "Texas State Historical Association".

- "The Franco-Texan Land Company".

- "The Franco-Texan Land Company".

- "The Franco-Texan Land Company".

- "The Franco-Texas Land Company".

- "Texas State Historical Association".