Peter Schlumbohm

Peter Schlumbohm (July 10, 1896 – 1962) was a German inventor, best known for creating the Chemex Coffeemaker. In a eulogy for Schlumbohm shortly after his death in 1962, the notable design author Ralph Caplan described the typical Schlumbohm invention as “a synthesis of logic and madness”. Caplan, like hundreds of thousands of Americans, was particularly fond of the Chemex Coffeemaker, describing it as “one of the few modern designs for which one can feel affection as well as admiration.” The Chemex was also one of the few products from any designer or inventor of the time to achieve an "iconic" role in popular culture, becoming part of the permanent collections of art and design museums, including New York's Museum of Modern Art.

Life in Germany

Schlumbohm was born July 10, 1896 in Kiel, Germany,[1] “…the oldest son of a well-to-do manufacturer of paints and chemicals, who was very jolly and very Lutheran.” Only six months after graduating the German equivalent of high school, Schlumbohm was conscripted into the German army, fighting in the landmark battles of Ypres and Langemark as an artillery brigade captain. Immediately upon his return from France in 1918, Schlumbohm gave up his inheritance in his father's chemical business in exchange for an agreement with family members to support his education for as long as he wished to stay in school. According to Schlumbohm, “My father was horrified when I waived my birthright and ‘lifelong security’ and named my only goal: to find out what had caused the mess of a war and to study as long as I wished to.” Schlumbohm himself professed admiration for the abortive post-war revolutionary movement, recounting his mother’s enthusiasm at the sight of the summary execution of military officers by revolutionary mutineers in Kiel in 1918. A year later, in an article in a University of Hamburg magazine, Schlumbohm called for the abolition of the military, and the implementation of technocratic leadership in the German state. Along with his chemistry classes, Schlumbohm studied Gestalt Psychology under one of its founders, the psychologist Wolfgang Köhler.

Schlumbohm received his doctorate in Chemistry from the University of Berlin. After leaving University, Schlumbohm spent the next four to five years in a semi-itinerant manner, supporting himself through the sale of patents and inventions to various manufacturers in Germany, France and England. Schlumbohm worked for some years perfecting a color-correcting mirror, initially marketed to theaters.

In the United States

Schlumbohm first visited the United States in 1931,[1] in connection with attempts to sell patent rights related to the manufacture of carbon-dioxide, or ‘dry’, ice. Despite advice from business contacts that business conditions were desperate, Schlumbohm was confident enough, or desperate enough, to make the trip that same year. Once in the U.S, Schlumbohm was able to sell patents for vacuum bottle designs to the American Thermos Bottle Company for $7,000. America's patent laws held a great attraction for Schlumbohm after this first experience, and his later writings credit the patent regulations of the U.S. as the main reason for his relocation to the country, overcoming his distaste for the corporate mindset of American business.

The improvement of refrigeration through chemical, mechanical, and engineered processes was Schlumbohm's perennial interest throughout his working life. Between 1929 and 1941, out of 44 patents filed, at least 26 were directly related to this topic. Schlumbohm considered refrigeration to be one of the most important and necessary scientific fields, going so far as to state, “Our civilization is a function of the degree of vacuum man can produce industrially,” the production of vacuum being a critical component of refrigeration.

Inventing the perfect coffeemaker

The Chemex coffeemaker was a consequence of intersection of Schlumbohm's scientific and marketing interests. Between his first American trip in 1931 and the filing of the U.S. patent for Chemex, Schlumbohm applied for dozens of patents, focused on his core specialty of refrigeration but also wildly diverse. Patents included applications for a ‘method of illuminating rooms’, ‘unburnable gasoline’, a ‘writing utensil’, and a ‘show window’ among many others, most of which are assumed to have been produced for sale. The final event of the process which culminated in the marketing of the Chemex was Schlumbohm's final attempt to market the ‘open system’ transitory refrigeration cycle device which he had been perfecting for some years. A working prototype had been exhibited at the 1939 New York World's Fair, claiming to be the cheapest and simplest refrigeration system ever invented. Schlumbohm considered this to be the invention that would provide the financial independence he had been seeking since his graduation more than a decade before, and had in fact been working on versions of the same device since 1929. Finally, an investor offered to provide sufficient money to put the prototype into production, but demanded a controlling interest in the company which would produce the device. Schlumbohm refused the overture, which placed him in a difficult financial predicament. “To afford that refusal, I had to take an appraising look at the other arrows in my quiver. There was this new patent for the coffeemaker, with its broad appeal. Within a week, I had sold half-an-interest in it for $5000 and planned to license it.”

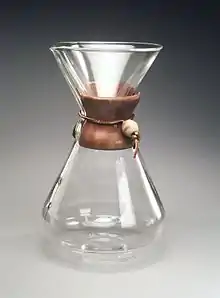

Schlumbohm's patent No. 2,241,368 for a ‘Filtering Device’ had been filed on April 13, 1939. The original version included a spout and handle, much more complex than the final familiar version, and was intended for multiple uses, including laboratory filtering processes.

Icon of wartime design

The Chemex Corporation was incorporated in New York State in late 1939. The directors were Schlumbohm himself, Isaac Harter, an acquaintance from Ohio, and Edward Turner who was given a minority holding of one share in order to meet the incorporation law's requirement that two thirds of a company's directorate be American citizens. Most significantly, Schlumbohm was finalizing the spoutless design for the coffeemaker, with its pouring groove, level button, and vent, which was to become the familiar icon. By 1942 Schlumbohm had successfully interested Wanamakers and Macy's in his product and was faced with the problem of finding a manufacturer willing to handle the level of orders in the increasingly difficult wartime production environment. After successfully procuring approval from the War Production Board, Schlumbohm was able to enter into a production agreement with the Corning Glass Works. The simplicity of the design, and the materials and processes involved in its manufacture, immediately resonated with the predominant design sentiment of the time, which was a combination of the purism of the Bauhaus style, newly dominant in the U.S. in part due to the arrival from Nazi Germany of the German design diaspora, and the U.S. Government's propagandistic attempts to co-opt the design establishment into supporting the centralization of the economy. Schlumbohm was well aware of the advantageous situation that an all-glass product held against competing devices constructed of materials such as aluminum and chrome, materials whose supply was prioritized by armaments producers. The Chemex coffeemaker received a potent seal of approval from the design establishment in 1942, when it appeared on the cover of the Museum of Modern Art’s ‘Useful Objects in Wartime’ bulletin, making it the official poster-child of establishment's new emphasis on undecorated, functional simplicity, the rejection of streamlining as a decorative motif, and the use of non-priority materials, as well as the implicit populist sentiment presented in the bulletin's showcasing of objects and products manufactured in response to requests from servicemen for ‘useful objects’.

The 1950s

After the war, Schlumbohm continued his deliberative approach to maintaining the public profile of the Chemex line, not only through prominent placement in advertisement, trade shows, and international expositions, but also in a generous gift-giving strategy, presenting Chemex coffeemakers to the famous cartoonist Charles Addams, perhaps hoping that Addams would place a Chemex in Gomez and Morticia's kitchen, or Grandpa's laboratory. Schlumbohm also made his invention part of the political scene, presenting coffeemakers to President Harry S. Truman and Lyndon B. Johnson. When stationed in London, Ian Fleming's James Bond always had very strong coffee brewed in an American Chemex (From Russia With Love).

References

- "Peter Schlumbohm | Lemelson-MIT Program". lemelson.mit.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-05.

External links

- MOMA's collection of Schlumbohm's work is available online

- Chemex Corporation's biography

- The Hagley Museum and Library has a collection of Schlumbohm's scrapbooks and correspondence in series III of the Marc Harrison papers.

- Chemex Coffee Maker Brewing Instructions

- Dr. Chemex, Tejal Rao, Gourmet Magazine, June 10, 2008