Pennyfield Lock

The Pennyfield Lock (Lock #22) and lockhouse are part of the 184.5-mile (296.9 km) Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal) that operated in the United States along the Potomac River from the 1830s through 1923. The lock, located at towpath mile-marker 19.7, is near River Road in Montgomery County, Maryland. The original lock house was built in 1830, and its lock was completed in 1831.

Pennyfield Lock and lock house in 2020 | |

| Waterway | Chesapeake and Ohio Canal |

|---|---|

| Country | USA |

| State | Maryland |

| County | Montgomery |

| Operation | Defunct |

| Coordinates | 39.05372°N 77.28887°W |

| Towpath milemarker 19.7 | |

The name "Pennyfield" is a misspelling of the family name of long-time lock keepers George and Charles Pennifield. George, and then his son Charlie, operated the lock from the 1880s until it was permanently closed. George was an avid fisherman, and once hosted President Grover Cleveland for several days of fishing near the lock.

Today, the lock and restored lock house are part of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park. The area is a favorite of bird watchers, and the Pennyfield Lock Neighborhood Conservation Area and Dierssen Wildlife Management Area are both accessible using the lock's towpath.

Background

Ground was broken for construction of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal (a.k.a. C&O Canal) on July 4, 1828.[1] One of the early plans was for the canal to be a way to connect the Chesapeake Bay with the Ohio River—hence the name Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.[2] The canal has several types of locks, including 74 lift locks necessary to handle a 608-foot (185 m) difference in elevation between the two ends of the canal—an average of about 8 feet (2.4 m) per lock.[3] From Georgetown to Harpers Ferry, which includes Lock 22 (Pennyfield Lock), the canal is 60 feet (18 m) wide at the surface, and 42 feet (13 m) at the bottom. Including walls, lift locks are 100 feet (30 m) long and 15 feet (4.6 m) wide—usable lockage is less.[4]

Portions of the canal (close to Georgetown) began operating in the 1830s, and construction ended in 1850 without reaching the Ohio River.[5] The canal ran from Georgetown to Cumberland, Maryland. Because portions of the Potomac can be shallow and rocky as well as subject to low water and floods, the river could not serve for reliable navigation and a continuous canal on land was necessary.[6] The canal opened the region to important markets and lowered shipping costs. By 1859, about 83 boats per week were using the canal to transport coal, grain, flour, and farm products to Washington and Georgetown.[7]

The canal faced competition from other modes of transportation, especially the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O Railroad). Starting in Baltimore and adding line westward, the B&O Railroad eventually reached the Ohio River and beyond.[1] In 1889, a flood damaged the C&O Canal and caused the C&O Canal Company to enter bankruptcy.[8] Operations stopped for about two years. Trustees nominated by the B&O Railroad took over receivership of the canal and began operating it under court supervision, but canal use had already peaked in the 1870s.[9] The C&O Canal closed for the season in November 1923, and damage from flooding prevented it from opening in spring 1924.[10] The damage and continued competition from railroads and trucks led to the decision to close permanently later that year.[11]

History

Work on Lock 22 began in April 1829 and was completed in May 1831 at a cost of $7,969.29 (equivalent to $191,338 in 2019).[12] Construction of the lock house began in October 1829, and was finished April 1830 at a cost of $853.20 (equivalent to $20,485 in 2019).[13] On August 7, 1830, an individual listed only as "Wright" was recommended and approved as lock keeper. His annual compensation was $100 (equivalent to $2,401 in 2019) with the additional benefits of the use of the lock house and the right to use the canal company's land between the canal and the Potomac River below a creek known as the Muddy Branch.[14]

By June 1832, a 22-mile (35 km) section of the canal was operating between Georgetown and Seneca, which includes Lock 22.[15] Another early keeper for Lock 22 was M. F. Harris, who was lock keeper (a.k.a. locktender) on July 1, 1839.[16] John Fields is listed as lock keeper on July 1, 1841.[17]

Another locktender, R. Selby, is listed for 1865.[18] A map of Montgomery County, Maryland, shows Selby as the "L.K." (lock keeper) and a nearby wharf owned by John L. DuFief.[19] DuFief built a mill around 1850 on the Muddy Branch, and it had a road that connected to Lock 22.[20] His mill had the capacity to manufacture 10–12,000 barrels of flour per year, and a network of roads grew that enabled farmers to get their crops to the mill and canal.[20] The same 1865 map shows a lock keeper named G. W. Pennifield for a lock west of Selby's Lock 22—probably Lock 23.[19] In 1875, the Lock 22 keeper, unnamed in the report, was dismissed after he drunkenly "opened the lower gate paddles before the boat was in place", causing the boat to break apart and sink with its 113-ton cargo.[21]

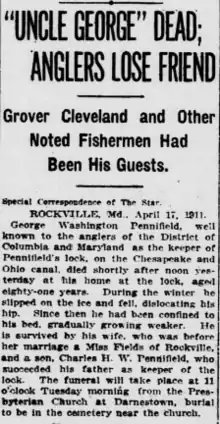

George Washington Pennifield became lock keeper for Lock 22 sometime during the 1880s.[Note 1] Pennifield became well known in Montgomery County, especially among fishermen. Grover Cleveland, while president, spent several days at Pennifield's Lock for a fishing trip—staying at Pennifield's home near the lock house.[25] Pennifield's son, Charles, eventually replaced him as lock keeper although the elder Pennifield continued to live at the Pennifield House near the lock house. George Pennifield died in 1911 and was buried at the Darnestown Presbyterian Church cemetery.[25]

Charles remained as lock keeper until the canal closed in 1924.[18][24] He lived with his wife at the lock house for over 50 years.[26] In 1938, they moved to Travilah, Maryland, and Charles died in 1941.[27] Although the Pennyfield Lock House remains, the larger Pennifield House fell into disrepair and was torn down in 2009.[28][29]

Today's Pennyfield Lock is a misspelling of the Pennifield family name.[30] The lock was described as "Pennifield's Lock" in George Pennifield's 1911 obituary.[25] However, the name was being misspelled as early as 1918.[31]

Today

Today, the Pennyfield Lock and restored lock house are part of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park.[32] The C&O Canal Trust describes the lock as a good example of "the basic types of structures" built along the canal, and the furnishings in the lock house are representative of the mid-1830s to mid-1840s.[33] The Pennyfield Lock House is one of seven restored lock houses on the C&O Canal available to the public for overnight stays as part of the Canal Quarters Program managed by the C&O Canal Trust.[34]

The Muddy Branch, a tributary to the Potomac River, is less than a half mile (0.8 km) walk on the canal towpath. The area has numerous birds and waterfowl and is a favorite of bird watchers.[32] Additional bird watching is available nearby along the towpath at the Pennyfield Lock Neighborhood Conservation Area, a 1.9 acre (0.77 ha) park with boat ramp maintained by Montgomery County.[35] The 40-acre (16 ha) Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary is also adjacent to the canal towpath and a favorite of bird watchers.[36][37][38]

Notes

Footnotes

- The exact start date for George Pennifield as lock keeper for Lock 22 has been lost. A report on the canal says that the April–May 1886 flooding washed away the towpath for Lock 22 and repairs needed "100 men at work under the direction of Lockkeeper Pennifield".[22] The same report also says that a warehouse at Lock 22 owned by George Pennifield was "carried away by 1889 flood".[23] A 1909 newspaper article describes him as being at Lock 22 for "nearly a quarter of a century".[24]

Citations

- "C&O Canal versus the B&O Railroad". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- Rubin 2003, p. 4

- "C&O Canal Association - The Complex World of Locks, Gates, and Dams". C&O Canal Association. Retrieved 2020-06-28.

- Unrau 2007, p. 226

- "Canal History: Canal Era from the 1830s-1870s". C&O Canal Trust. C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved 2020-03-31.

- "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal". Visit Maryland, Maryland Office of Tourism Development. Maryland Department of Commerce. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 18

- "Chesapeake and Ohio Canal - The C&O Canal's Legal Status 1889-1939". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- "Today in History - October 10 - The C&O Canal". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-06-18.

- "Canal to Close Season in Week". Daily Mail (Hagerstown, Maryland). 1923-11-13. p. 1.

The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal will be closed this week or early next week for the winter season.

- "Canal History: Decline and Eventual Closing of the C&O Canal". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved 2020-06-12.

- Unrau 2007, p. 229

- Unrau 2007, pp. 244–245

- Unrau 2007, p. 786

- Unrau 2007, p. 65

- Unrau 2007, p. 597

- Unrau 2007, p. 603

- "Chesapeake & Ohio Canal - Canal Workers". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- Martenet & Bond (1865). Martenet and Bond's Map of Montgomery County, Maryland (Map). Baltimore, Maryland: Simon J. Martenet. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- Kelly & Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission 2011, p. 12

- Unrau 2007, p. 799

- Unrau 2007, p. 309

- Unrau 2007, p. 694

- "At Pennyfield's Lock (page 9)". Washington Evening Star (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). 1909-08-21. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- Special Correspondence of the Star (1911-04-17). ""Uncle George" Dead; Anglers Lose Friend (page 2)". Washington Evening Star (from Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress). Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- "Mrs. Charles W. Pennifield". The News (Frederick, MD). 1950-10-18. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- "Mrs. Charles Pennifield Dies in Gaithersburg at 84". Evening Star (Washington, Library of Congress). 1950-10-17.

- Meyer, Eugene L. (2009-11-21). "When Presidents Came to Visit". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- LaBarre, Ansley (2009-10-07). "Pennyfield House Demolished" (PDF). Potomac Almanac. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- High 2015, p. 126

- "Pennyfield Lock Below Seneca". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2020-06-29.

- "National Park Service - Birding By Day, A Night In Pennyfield Lockhouse". National Park Service. U.S. Department of the Interior. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- "Lockhouse 22". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- "Canal Quarters". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved 2020-07-15.

- "Montgomery Parks - Pennyfield Lock Neighborhood Conservation Area". Montgomery Parks. Montgomery County, Maryland government. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- "Dierssen Waterfowl Sanctuary". C&O Canal Trust. Retrieved 2020-07-01.

- "Maryland Department of Natural Resources - Dierssen WMA". Maryland Department of Natural Resources. Maryland government. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

- "C&O Canal – Pennyfield, Violette's & Riley's Locks". Maryland Ornithological Society. Retrieved 2020-06-26.

References

- High, Mike (2015). The C & O Canal companion: A Journey through Potomac History. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-42141-505-5. OCLC 876370927.

- Kelly, Clare Lise; Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission (2011). Places from the Past: The Tradition of Gardez Bien in Montgomery County, Maryland - 10th Anniversary Edition (PDF). Silver Spring, Maryland: Maryland-National Capital Park and Planning Commission. ISBN 978-0-97156-070-3. OCLC 48177160. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Rubin, Mary H. (2003). The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia. ISBN 978-1-43961-250-7. OCLC 904439352.

- Unrau, Harlan D. (2007). Historic Resource Study: Chesapeake & Ohio Canal (PDF). Hagerstown, Maryland: National Park Service - United States Department of Interior. OCLC 184689456.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pennyfield Lock. |