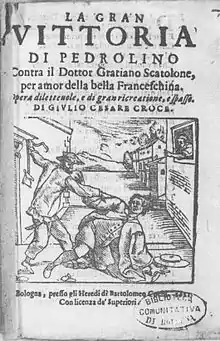

Pedrolino

Pedrolino is a primo zanni, or comic servant, of the Commedia dell'Arte; the name is a hypocorism of Pedro (Peter), via the suffix -lino. The character made its first appearance in the last quarter of the 16th century, apparently as the invention of the actor with whom the role was to be long identified, Giovanni Pellesini. Contemporary illustrations suggest that his white blouse and trousers constituted "a variant of the typical zanni suit",[1] and his Bergamasque dialect marked him as a member of the "low" rustic class.[2] But if his costume and social station were without distinction, his dramatic role was certainly not: as a multifaceted "first" zanni, his character was—and still is—rich in comic incongruities.

Many Commedia historians make a connection between the Italian Pedrolino and the later Pierrot of the French Comédie-Italienne, and, although a link between the two is possible, it remains unproven and seems unlikely, based on the scant evidence of early Italian scenario texts.[3]

Type, plot-function, and character

Pedrolino appears in forty-nine of the fifty scenarios of Flaminio Scala's Il teatro delle favole rappresentative (1611) and in three (undated) pieces of the "Corsini" collection of manuscripts;[4] he also appears (as "Pedrolin") in a 1587 scripted comedy by Luigi Groto, La Alteria.[5] All of these provide evidence of how he was conceived and played. He is obviously a type of what Robert Storey calls the "social wit", usually incarnated as "the go-between, the willing servant, the wily slave" who "survives in serving others".[6] In the Scala scenarios, which offer the most revealing showcase of his character, he is invariably cast as the "first" zanni, a type to be distinguished from the "second" zanni by his or her function in the plot. The Commedia critic and historian Constant Mic clarifies the distinctions when he notes that the first zanni

instigates confusion quite voluntarily, [but] the second creates disturbance through his blundering. The second zanni is a perfect dunce; but the first sometimes gives indication of a certain instruction. ... The first zanni incarnates the dynamic, comic element of the play, the second its static element.[7]

Since his function is "to keep the play moving",[8] Pedrolino seems to betray, in Storey's words, "a Janus-faced aspect": "He may work cleverly in the interests of the Lovers in one play—Li Quattro finti spiritati [The Four Fake Spirits], for example—by disguising himself as a magician and making Pantalone believe that the 'madness' of Isabella and Oratio can be cured only by their coupling together; then, in Gli avvenimenti comici, pastorali e tragici [Comic, Pastoral, and Tragic Events], indulge his capricious sense of fun by compounding the young persons' misfortunes."[9] So multiform is his character that his cleverness can often give way to credulity (as when he is tricked into believing that he was drunk when he learned of his wife's infidelity and so merely imagined the whole affair) and his calculation can sometimes be routed by grotesque sentimentality (as when he, Arlecchino, and Burratino share a bowl of macaroni, the three blubbering all the while).[10] Despite such inconsistencies in character and behavior, he has (or at least had, for his Renaissance audiences) an "instantly recognizable" identity. "The recognizability came," as Richard Andrews writes, "from his costume; from his body language; and most of all from his style of speech, which for Italian audiences was based on a regional dialect as well as more personal idiosyncrasies."[11] That recognizability also arose from his puckish love of mischief: "He takes a child-like delight in practical jokes and pranks," as a modern-day practitioner of the Commedia writes, "but otherwise his intrigues are on behalf of his master. ... At times, however, the best he can scheme for is to escape the punishment others have in store for him."[12] Naively volatile, he can be moved to violence when angry, but, in obedience to the conventions of comedy, his pugnaciousness is usually deflected or foiled.

Pedrolino is most often presented as having an all-white wardrobe and wearing exaggeratedly over-sized and loose-fitting clothes, typically including a white jacket with large buttons and comically long sleeves, a large neck ruff, and a large, floppy hat.[13] He is one of the few unmasked male characters that was not an Innamorati. Instead of a mask, Pedrolino is said to have been defined, according to some Commedia historians, by a white "floured" makeup, also known as infarinato, which later inspired, in part, the makeup of the modern-day white-faced clown.[14]

Pellesini

Pedrolino first appears among the records of the Commedia in 1576, when his interpreter Giovanni Pellesini (c. 1526-1616) turns up in Florence, apparently leading his own troupe called Pedrolino.[15] A member of some of the most illustrious companies of the 16th and 17th centuries—the Confidenti, Uniti, Fideli, Gelosi, and Accessi[16]—Pellesini was obviously "a much sought-after and highly paid guest star".[17] His status is underscored by the fact that Pedrolino figures so prominently in Scala's scenarios, since, as K.M. Lea convincingly argues, Scala, in compiling them, drew upon the "chief actors of his day ... without regard to the composition of a company at any particular period."[18] Pedrolino—and Pellesini—were, we must conclude, among the brightest luminaries of the early Commedia dell'Arte.

Pellesini had a lengthy run as Pedrolino and performed for a number of high-ranking spectators, including the Duke of Mantua at Fontainebleau while traveling with the Confidenti. His last appearance as Pedrolino was in 1613 at the age of eighty-seven, performing with the Accessi company at the court theater of the Louvre,[19] an engagement to which the poet Malherbe responded:

Harlequin is certainly quite different from what he was, and so is Petrolin [i.e., Pedrolino]: the first is fifty-six and the second eighty-seven. These are no longer proper ages for the theater; gay spirits and sharp wits are needed there, and one hardly finds these in bodies as old as theirs.[20]

Pedrolino and Pierrot

Since the names of the two types translate into the same diminutive ("Little Pete") and they enjoy (or suffer) the same dramatic and social status, as comic servants, in the Commedia, many authors have concluded that Pedrolino is either the "Italian equivalent" or the direct ancestor of the 17th-century French Pierrot.[21] But there is no documentation from that century that establishes a clear connection between the two types. "Dominique" Biancolelli, Harlequin of the first Paris-based Italian troupe in which Pierrot appeared by name, contended that Pierrot was conceived as a Pulcinella, not a Pedrolino: "The nature of the rôle," he wrote,

is that of a Neapolitan Pulcinella a little altered. In point of fact, the Neapolitan scenarii, in place of Arlecchino and Scapino, admit two Pulcinellas, the one an intriguing rogue and the other a stupid fool. The latter is Pierot's [sic] rôle.[22]

A more direct source is the patois-spouting and lovelorn peasant Pierrot of Molière's play Don Juan, or The Stone Guest (1665). Some eight years after its highly successful premiere, the Italians spoofed Molière's comedy with an Addendum to "The Stone Guest", in which Pierrot first appeared by name among his fellow masks;[23] he was played by one Giuseppe Giaratone, an actor who thereafter would be identified with the character for the next quarter-century.[24] Like Molière's, Giaratone's Pierrot would also prove to be lovelorn, subject to a malady that does not afflict Pedrolino.[25] And, notwithstanding Giaratone's usually playing Pierrot as an Italianate zanni, it is probably no accident that, in several of the plays left behind by his troupe, Pierrot is portrayed as a patois-spouting peasant in the French mold.[26]

Pedrolino and Pierrot are clearly differentiated by their respective functions in the plots of their plays. Pedrolino, as a first zanni, is, as Mic notes above, the "dynamic" element of the play; Pierrot, on the other hand, as a second zanni, is static. The latter appears, as Storey writes, "in comparative isolation from his fellow masks, with few exceptions, in all the plays of Le Théâtre Italien, standing on the periphery of the action, commenting, advising, chiding, but rarely taking part in the movement around him."[27] Pedrolino, by contrast, is not a character to be caught standing still.

Notes

- Katritzky, p. 248.

- So asserted Bartolomeo Rossi in the foreword to his 1584 pastoral play Fiamella, p. 3. See also Andrews, p. xxiv.

- Andrews, pp. xxv–xvi.

- The Scala scenarios have been translated by Salerno; the plots of the "Corsini" pieces have been summarized by Pandolfi (V, 252-76). As Storey (1978) notes, at least one of Pandolfi's summaries "gives indication that [Pedrolino] may enjoy here different nuances of character from those of Scala's zanni: in Il Granchio [The Crab] he appears to be a father on equal footing with Pantalone" (p. 15, n. 23).

- Groto, Luigi (1541-1585) (1612-01-01). La Alteria , comedia di Luigi Groto, cieco d'Hadria. Novamente ricorretta e ristampata.

- Storey (1996), pp. 170, 171.

- Mic, p. 47; tr. Storey (1978), p. 13 (emphasis Storey's).

- Storey (1978), p. 13.

- Storey (1978), pp. 15-16.

- The parenthetical examples are from two plays in the Scala collection, La Fortunata Isabella (Lucky Isabella) and Il Pedante (The Pedant).

- Andrews, pp. xix, xx.

- Rudlin, p. 136.

- "Pedrolino | stock theatrical character". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- "Faction of Fools | A History of Commedia dell'Arte". www.factionoffools.org. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- For the movements of this troupe and of Pellesini himself, see Lea, I, 265-92.

- A detailed account of these troupes and of Pellesini's movements among them is given by Rudlin and Crick, pp. 1-53.

- Katritzky, p. 249.

- Lea, I, 293.

- Rudlin and Crick, p. 27.

- Ludovic Lalanne, vol. 3, p. 337, has the original French: "Arlequin est certainement bien différent de ce qu'il a été, et aussi est Petrolin : le premier a cinquante-six ans et le dernier quatre-vingts et sept; ce ne sont plus âges propres au théâtre : il y faut des humeurs gaies et des esprits délibérés, ce qui ne se trouve guère en de si vieux corps comme les leurs."

- "Italian equivalent" is Nicoll's phrase ([1963], p. 88); Mic writes that the historical connection between Pedrolino and Pierrot is "absolutely evident" (p. 211). Sand and Duchartre assume a close kinship between the two characters, as does Oreglia; Storey (1978) sees Pedrolino and Hamlet as establishing behavioral "poles" for Pierrot, between which he oscillates throughout his long history (pp. 73-74). As late as 1994, Rudlin (pp. 137-38) renames Pierrot "Pedrolino", in a translation of a scene from Arlequin, Empereur dans la lune, first performed in 1684 and published in the Gherardi collection, vol. 1, p. 179.

- MS 13736, Bibliothèque de l'Opéra, Paris, I, 113; cited and tr. Nicoll (1931), p. 294.

- Both masked and unmasked characters of the Commedia were known as "masks": see Andrews, p. xix.

- See Storey (1978), pp. 17-18.

- "Pedrolino's love for Franceschina sometimes provides the occasion for a farcical scuffle between him and Arlecchino (Li Duo vecchi gemelli [The Two Old Twins]) or for a burst of jealous anger when he is cuckolded by Doctor Gratiano (La Fortunata Isabella [Lucky Isabella]). But it never elicits the tenderness, both comic and pathetic, that infuses [a] scene of Regnard's La Coquette (1691), in which Pierrot stands tongue-tied with love before his master's young daughter, Columbine": Storey (1978), pp. 25-26. For the scene, see Gherardi, vol. 3, pp. 100-102.

- See, e.g., Act III, scene iii of Eustache Le Noble's Harlequin-Aesop (1691) in the Gherardi collection.

- Storey (1978), pp. 27-28. Le Théâtre Italien is the Gherardi collection cited in "References" below.

References

- Andrews, Richard (2008). The Commedia dell'Arte of Flaminio Scala: A Translation and Analysis of 30 Scenarios. Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810862074.

- Duchartre, Pierre-Louis (1929; Dover reprint 1966). The Italian Comedy, translated by Randolph T. Weaver. London: George G. Harrap and Co., Ltd. ISBN 0-486-21679-9.

- Gherardi, Evaristo, editor (1721). Le Théâtre Italien de Gherardi ou le Recueil général de toutes les comédies et scènes françoises jouées par les Comédiens Italiens du Roy ... 6 vols. Amsterdam: Michel Charles le Cène. Vols. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 at Google Books.

- Katritzky, M.A. (2006). The Art of commedia: a study in the Commedia dell'Arte 1560-1620 with special reference to the visual records. Amsterdam, N.Y: Editions Rodopi B.V. ISBN 90-420-1798-8.

- Lalanne, Ludovic, editor (1862). Oeuvres de Malherbe, vol. 3. Paris: Hachette. Copy at Gallica.

- Lea, K.M. (1934). Italian popular comedy: a study in the Commedia dell'Arte, 1560-1620, with special reference to the English stage. 2 vols. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mic, Constant (1927). La Commedia dell'Arte, ou le théâtre des comédiens italiens des XVIe, XVIIe & XVIIIe siècles. Paris: J. Schiffrin.

- Nicoll, Allardyce (1931). Masks, mimes and miracles. London: Harrap & Co.

- Nicoll, Allardyce (1963). The World of Harlequin: a critical study of the commedia dell'arte. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Oreglia, Giacomo (1968). The Commedia dell'Arte, translated by Lovett F. Edwards. New York: Hill and Wang. First published in Italian in 1961, revised in 1964. ISBN 9780809005451.

- Pandolfi, Vito (1957–1969). La Commedia dell’Arte, storia e testo. 6 vols. Florence: Sansoni Antiquariato.

- Rossi, Bartolomeo (1584). Fiammella pastorale. Paris: Abel L'Angelier.

- Rudlin, John (1994). Commedia dell'Arte: an actor's handbook. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-04770-6.

- Rudlin, John & Olly Crick (2001). Commedia dell'Arte: a handbook for troupes. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-20409-7.

- Salerno, Henry F., translator (1967). Scenarios of the Commedia dell’Arte: Flaminio Scala's Il teatro delle favole rappresentative. New York: New York University Press.

- Sand, Maurice (Jean-François-Maurice-Arnauld, Baron Dudevant, called) (1915). The History of the harlequinade [orig. Masques et bouffons. 2 vols. Paris: Michel Lévy Frères, 1860]. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

- Storey, Robert F. (1978). Pierrot: a critical history of a mask. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-06374-5.

- Storey, Robert (1996). Mimesis and the human animal: on the biogenetic foundations of literary representation. Evanston, Il.: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0-8101-1458-5.