Peace Through Law Association

The Peace Through Law Association (French: APD: Association de la paix par le droit) was a French pacifist organization active in the years before World War I (1914–1918) that continued to promote its cause throughout the inter-war period leading up to World War II (1939–1945). For many years it was the leading organization of the fragmented French pacifist movement. The APD believed that peace could be maintained through an internationally agreed legal framework, with mediation to resolve disputes. It did not support individual conscientious objection, which it thought was ineffective. It would not align with the left-wing "peace at all costs" groups, or with the right-wing groups that thought the League of Nations was all that was needed.

Association de la paix par le droit | |

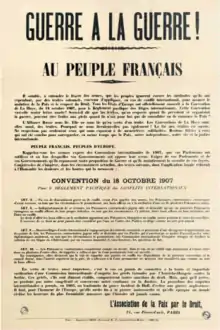

ADP poster calling for War on War! Issued at the start of World War I. | |

| Abbreviation | APD |

|---|---|

| Formation | 7 April 1887 |

| Dissolved | 1948 |

| Type | Non-governmental organization |

| Legal status | Defunct |

| Purpose | Pacifism |

| Headquarters | Nîmes, France |

Region | France |

Official language | French |

Background

Several pacifist organizations were active in France in the late 19th century and early 20th century. The French Society for Arbitration Between Nations (Société française pour l’arbitrage entre les nations) was founded by Frédéric Passy (1822–1912), who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1901. The International League for Peace and Freedom (LIPL: Ligue internationale de la paix et de la liberté) was founded in Geneva in 1867 and was chaired by Charles Lemonnier (1860–1930). The LIPL was based in Switzerland until 1919, but had a Paris committee headed by Émile Arnaud (1864–1921), who became president of the League in 1891. The League published a monthly journal, Les États-Unis d’Europe (The United States of Europe).[1]

Foundation

Louis Barnier, who founded the organization, met the English Quaker and leader of the Wisbech Local Peace Society Priscilla Hannah Peckover (1833–1931) while he was a student in England.[2] From the Quakers he became converted to the concept of peace through arbitration. On his return he shared this new faith with his teenage friends in Nîmes. They formed a focus group called "The Wave" (la Gerbe).[3] The association was founded on 7 April 1887 by six students led by Théodore Eugène César Ruyssen (1868–1967).[1] At first it was named the Association of Young Friends of Peace (Association des jeunes amis de la paix).[4] It was Protestant in nature, influenced by utopian socialism and by the cooperative school of Nîmes, which reflected the ideas of Charles Gide (1847–1932), Emmanuel de Boyve and Auguste Marie Fabre (1833–1922). Fabre was particularly influential on the young peace activists.[1]

Early years

At first the association reflected the reforming Huguenot origins of most of the members, but soon developed more legalistic, internationalist and positivist views.[3] The group denounced military service, and Barnier left France rather than accept enlistment, but eventually the others moved to a less radical position.[2] In 1895 the association took the name of Peace Through Law Association (APD: Association de la paix par le droit).[4] The APD stated that its purpose was to "study and popularize the juridicial solutions for international conflicts and particularly to gain support for this position by the activity of young persons without distinction of sex.[2] The early members of the student group such as Charles Brunet and Jacques Dumas were in favor of founding a political party that would work towards pacifist goals.[5]

During the 1890s the APD became the dominant French peace association, replacing the Society for Arbitration.[1] Starting in 1902 the French pacifist societies began to meet at a National Peace Congress, which often had several hundred attendees.[1] However, they were unable to unify the pacifist forces apart from setting up a small Permanent Delegation of French Pacifist Societies in 1902, led by Charles Richet (1850–1935), with Lucien Le Foyer as Secretary-General.[1] The 1902 Peace Conference was held in Monaco. The British Peace Society did not send representatives, since they considered the location "one of the blackest and most deadly moral plague spots in the whole world."[4]

The feminist writer and teacher Jeanne Mélin was influenced by the socialist and pacifist Jean Jaurès.[6] From 1900 to 1914 Mélin fought for a moderate pacifism based on arbitration of disputes as a member of the ADP.[7] Mélin, who also belonged to the Societé d'education pacifique, led the APD in the Auvergne.[8] The association published the journal La Paix par le droit (Peace through Law) for over fifty years, disseminating intellectual and pacifist analysis of the international situation.[9] There were 8,000 subscribers to La Paix par le droit in 1914, on the eve of World War I (1914–18).[3]

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace provided support to the APD as well as to the Comité de conciliation internationale.[10] In 1911 Théodore Ruyssen, president of the APD, issued a report that concluded that, "Any lasting solution to the problem of disarmament must be subordinated to achieving durable security through the construction of a juridical international system capable of pushing aside or resolving disputes between nations." The report formed the basis for discussion by a national congress of French peace organizations that met on 5 June 1911 to consider what conditions were needed for international disarmament.[11]

On 28 July 1914 Austria declared war on Serbia, the opening move in the war. The APD sent urgent telegrams to the European chancelleries reminding them that under the Hague Conventions they had agreed to use arbibration before going to war, and put up posters throughout Paris calling for peaceful solutions to the issues.[12] During World War I the association avoided defeatism, and took a position of "patriotic pacifism." Despite this, the journal was often subject to censorship.[9] In June 1915 the APD published a "minimum program" for building an international order after the war. It called for self-determination, the completion of the juridical project undertaken at the Hague peace conferences, and the constitution of a "society of peaceful nations committed to compulsory arbitration.[13]

Interwar period

After World War I the APD was unable to forgive the Germans and Austrians, whom they felt bore full responsibility for the war and had used brutal methods of waging war.[9] The German pacifist Dr. Alfred Hermann Fried wrote in 1920 that he regretted that the victory of democracy had not resulted in a democratic peace, and that the Treaty of Versailles was radically anti-pacifist. Two months later Jules L. Puech, editor of the APD journal, wrote that he could not suddenly come to love the people whom he had been fighting. Théodore Ruyssen expressed similar views in 1922.[14]

By the early 1920s the association led the French pacifist movement, which remained highly fragmented. There were 5,000 subscribers to La Paix par le droit in 1920, rising to 8000 in 1924, then declining to 5,300 by 1935.[3] In the 1920s the APD launched a second journal, Les Peuples unis (The United Peoples), aimed at a more popular readership. Every year the APD published a booklet titled Jeunesse et la paix du monde (Youth and World Peace) that was distributed worldwide. 108,000 copies of French version of the booklet were printed in 1933, and almost 250,000 copies in Dutch, Polish, English, Welsh, Esperanto, Chinese and Malay. Members of the association spread the message through public lectures and organized pacifist summer schools.[9]

At the 23rd International Peace Conference in Berlin in 1924 a growing divergence was evident between the moderate and intransigent camps of pacifists. The APD wanted to work towards a system of international law through which peace could be "organized", and felt that abstract and inflexible ideological statements damaged the cause.[3] In 1925 the APD debated the question of conscientious objection, which it rejected in a heated debate as an unacceptable individual approach based on faith. This issue was a divisive topic throughout the 1920s. The APD did not think the problem of peace could be solved through a purely individual point of view, but did call for immediate definition of the status of conscientious objectors.[14]

During the 1930s the APD saw Adolf Hitler seize power, the 1932-33 World Disarmament Conference end in failure, France standing aside as Italy invaded Ethiopia and a resurgent Germany reoccupying the Rhineland. All these events showed that the legal edifice to preserve peace had failed.[14] The APD during this period wanted to avoid interference in domestic politics or the affairs of other countries. It favored sanctions against Italy, but was against involvement in the Spanish Civil War for fear that it would escalate into an international conflict.[15]

The Communist-dominated World Committee Against War and Fascism was formed by the leaders of the Congress of Amsterdam in 1932 and the Congress of the Salle Pleyel in 1933.[16] The APD would not cooperate with this "radical" organization or with the International League of Peace Fighters (Ligue internationale des combattants de la paix).[15] In 1934, with the weakness of the League of Nations becoming clear, the APD rejected the idea of merging with other members of the French Federation for the League of Nations. It maintained its central position between the left-wing "peace at any price" school and the right-wing school that felt the League of Nations was the final goal of pacifism.[3] In 1938, despite the growing tensions that would lead to World War II (1939–1945), the APD remained convinced of its ideals and optimistic about a more peaceful future.[15]

The APD disappeared in 1948.[3]

See also

References

- Guieu 2005.

- Cooper 1991, p. 57.

- Ingram 1993, p. 2.

- Ceadel 2000, p. 139.

- Cooper 1991, p. 163.

- Jeanne Mélin ... Archives départementales des Ardennes.

- Vahe 2009, p. 85.

- Cooper 1991, p. 63.

- Ingram 1993, p. 3.

- Jackson 2013, p. 64.

- Jackson 2013, p. 1.

- Cooper 1991, p. 186.

- Jackson 2013, p. 127.

- Ingram 1993, p. 4.

- Ingram 1993, p. 5.

- Davies 2014, p. 117.

Sources

- Ceadel, Martin (2000). Semi-detached Idealists: The British Peace Movement and International Relations, 1854-1945. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-924117-0. Retrieved 2015-03-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cooper, Sandi E. (1991-11-11). Patriotic Pacifism : Waging War on War in Europe, 1815-1914: Waging War on War in Europe, 1815-1914. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-536343-2. Retrieved 2015-03-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Davies, Thomas (2014-10-10). NGOs: A New History of Transnational Civil Society. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-025750-7. Retrieved 2015-03-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Guieu, Jean-Michel (2005). "6 - Tensions nationalistes et efforts pacifistes". La France, l’Allemagne et l’Europe (1871-1945) (in French). Retrieved 2015-03-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ingram, Norman (1993). "Pacifisme ancien style, ou le pacifisme de l'Association de la paix par le droit". Matériaux pour l'histoire de notre temps (in French) (30. S'engager pour la paix dans la France de l'entre-deux-guerres). Retrieved 2015-03-11.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jackson, Peter (2013-12-05). Beyond the Balance of Power: France and the Politics of National Security in the Era of the First World War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-03994-0. Retrieved 2015-03-12.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Jeanne Mélin, une féministe d'avant-garde 8 mars 2013". Archives départementales des Ardennes. Retrieved 2015-01-02.

- Vahe, Isabelle (2009). "Jeanne Mélin (1877–1964): une féministe radicale pendant la Grande Guerre". Femmes Face À la Guerre. Peter Lang. ISBN 978-3-03911-332-3. Retrieved 2014-11-14.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)