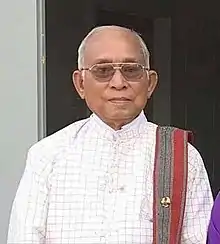

Pe Thein Zar

Pe Thein Zar (8 January 1943 – 30 July 2018) was a Mon courageous student leader, lawyer, revolutionary and freedom fighter, and writer. Pe Thein Zar had been imprisoned for seven years for his peace movement. He earned a BA (History) degree from Rangoon University.[1]

Pe Thein Zar နာဲဖေသိင်ဇြာ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Pe Thein February 19, 1942 Kamawet, Mudon Township, Mon State, Burma |

| Died | July 30, 2018 (aged 76) Canberra, Australia |

| Nationality | Burmese (Mon) |

| Education | lawyer, Bachelor Degree in History |

| Alma mater | Rangoon University |

| Known for | revolutionary and freedom fighter, writer. |

| Spouse(s) | Nyo Nyo Win |

| Parent(s) | Nai Maung Maung, Mi Chit Tin |

Brief personal history

Pe Thein Zar was born in Kamawet Village (town), Mudon Township, in Mon State, Burma on 8 January 1943. His parents were Nai Maung Maung and Mi Chit Tin. He had one brother and one sister. He attended No. 1 Moulmein (now Mawlamyaing) State High School for his secondary education and was a member of the Moulmein District Mon Student Union.[1] He married to Nyo Nyo Win.[2]

Student life and political movement

Pe Thein Zar passed his matriculation examination with a Physics Distinction (only about 3% passed the examination) in 1960. For further study he joined the Moulmein College in 1961, and became an executive member of the Moulmein College Mon Students’ Association and an executive member of the Moulmein College Students’ Union.[1][2]

In late 1961, he was again elected as the President of the Moulmein District Mon Students’ Association, and attended, along with other student leaders, Conference of All Burma Students Union (ABSU) which was held in the Student Union Building of Rangoon (now Yangon) University on 16 November 1961. That turned out to be the last of the ABSU's conference to be held in this building because it was famously dynamited by General Ne Win & co on 8 July 1962. In 1962 he became the General Secretary of the Moulmein College Mon Students’ Association.[1][2]

He completed the Intermediate Science course in 1962-63 academic year. In 1963, while studying for the BSc degree, he was elected as the President of the Students’ United Front of Moulmein Degree College, the strongest student organisation in the College. On 14 November 1963, when peace negotiations between the Revolutionary Council, led by General Ne Win, and the leaders of various armed resistance groups collapsed, student organisations from all over the country staged demonstrations to urge the Revolutionary Council to resume the peace talk as soon as possible.[1][2]

On 18 November 1963, he and other student leaders of the Moulmein Degree College, decided to occupy the College as part of their attempt to force the Revolutionary Council to continue the negotiation process. On the night of 2 December 1963, he was, together with other student leaders, arrested and imprisoned in the Moulmein Jail. While there he met Mon leaders, Nai Tun Thein, Nai Chan Mon, Nai Nonlar, Nai Kyaung, Nai Kon Balai and Nai Tin Aung, all of whom had been detained on 14 November 1963. After seven years of detention, he was released on 15 October 1970, but he was unable to resume my BSc degree course at Moulmein Degree College. He was told that the course was part of the old educational system that was no longer in place, that if he really wanted to get a degree, he had to start from first year again.[1][2]

In 1973, after passing the Higher Grade Pleader (HGP) Examination, he started practising as a lawyer in Moulmein from 1975. At the same time, he undertook a correspondent course at the Rangoon University and in 1979, after five years of hard study, he finally got his BA (History) degree from that University.[1][2]

Revolutionary and freedom fighter

In 1987, the Burmese Socialist Programme Party (BSPP) government unexpectedly announced the demonetization of the 100-Kyat-note again and it was for the third time to do so. Members of the public were shocked and appalled. Thousands of people lost all their savings as the 100- Kyat notes became waste papers in the blink of an eye. As their agonies went beyond their limits, some committed suicide. His friends and he saw that it was time for them to leave home and join one of the armed resistant groups to fight against the military junta.[2]

On 15 October 1987, Nai Tin Aung, Nai Aung Shein and he, along with 25 Mon students from the Moulmein University and high schools, went underground and joined the New Mon State Party (NMSP). Not very long after that he was elected as a member of the central committee of the NMSP. In the Thai-Burma areas, for the first time in his life, he heard unfamiliar terms such as ‘human rights’, ‘humanitarian aid’, ‘NGO’, ‘freedom of expression’, ‘freedom of the press’, and ‘freedom of assembly’, etc. ‘Free and fair election’ and ‘government accountabilities’ were also foreign terms to them.[3][2]

In January 1990, as a representative of the NMSP, he took up duties at the National Democratic Front (NDF) office at Mannerplaw, located in the headquarters building of the Karen National Union (KNU). In that year, the State Law and Order Restoration Council (SLORC) organised a free and fair general election. As had been expected, the National League for Democracy (NLD), led by Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, won a landslide victory. But unfortunately, the SLORC refused to transfer the power to the NLD. As a result, many elected members of the parliament went underground to join up with various armed resistance groups. Some arrived at NMSP and some at KNU areas. On 18 December 1990, with the support of the NMSP, the KNU, the Kachin Independence Organisation (KIO) and other ethnic groups, the National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB), led by Dr. Sein Win, a cousin of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi, was established at Mannerplaw.[3][2]

In 1992, the National Council of the Union of Burma (NCUB) was founded by representatives of the NDF, NCGUB, and the Democratic Alliance of Burma (DAB). He was a member of the NCUB. When the Burma Lawyers’ Council (BLC) was formed in Mannerplaw, he became a member of it as well. At the Third Congress of the NDF that was held at Mannerplaw in 1992, he was elected as a committee member responsible for foreign affairs, while Nai Shwe Kyin (the President of NMSP) was elected as its President. Also in 1992, when the NDF decided to establish the Federal University, in order to provide education for those students who were involved in the 1988 pro-democracy uprising and who had fled to the armed resistance group areas, he was assigned to take charge of that university. In February 1993, he attended a diplomacy training course, organised by Jose Ramos Hota who was later to become the second president of East Timor), at the University of New South Wales.[3][2]

In October 1993, under a programme of the UN International Indigenous Year, he led a delegation of NDF representatives to several European countries, to draw attention to the plight of the ethnic minorities of Burma under the Burmese military regime – to the gross human rights abuses, forced labour, rapes, murder and arbitrary arrests committed by the Burmese armed forces in the ethnic minority areas. He also took the opportunity of explaining about the fundamental objective of the ethnic minorities armed resistance groups, namely, to establish a genuine federal union in Burma, so that every ethnic group could enjoy the rights of self-determination, equity and justice. In November 1993, he attended a UN Human Rights Commission seminar in Geneva, Switzerland where he met many representatives from various countries around the world.[3][2]

He stayed in Mannerplaw, KNU HQ, until the SLORC troops came and occupied it on 27 January 1995. Not very long after that, while he was in Mae Sot, Thailand, he learned that the NMSP was going to sign a ceasefire agreement with the SLORC. He made a haste trip back to the NMSP areas, but, as he had to travel circuitously through jungle routes in KNU-controlled areas, he could only get back to the NMSP areas in July 1995, during the rainy season, with a member of his staff, Nai Banya. I gratefully acknowledge the assistance rendered to me by the late Pha Do Man Sha (who later became the secretary of the KNU and subsequently assassinated), who organised my trip through the KNU areas to Sangkhlaburi, Thailand. On their way to Sangkhlaburi, they had to pass a mining area where his old friend, Dr. Banyar Aung Moe, was working as a medical doctor. After they took rest in his house for three days, he sent them with his car to Thong Pha Phum town, from where they had to take a bus to get to Sangkhlaburi. When they arrived at Sangkhlaburi, he immediately sent a message by wireless to the NMSP's HQ to wait until his return before making any major decision concerning on the ceasefire agreement. But, in any event, his message was apparently totally ignored.[3][2]

Resettlement in Australia

As he could not accept the ceasefire agreement reached between the NMSP and the SLORC on 29 June 1995, as a gesture of objection, he resigned from the post of NMSP committee member responsible for foreign affairs as well as a member the Party. Not very long after that, he went to Bangkok with his wife, Nyo Nyo Win, and applied for refugee status at the UNHCR office. About five months later, both were recognised as persons-of-concern, that is, refugees, by the UNHCR. After staying at the Maneeloi Refugee Camp in Thailand for about six months, on 26 November 1996, he and his wife migrated to Australia.[2]

When their plane touched down at Canberra Airport on 27 November 1996, to their surprise they found ourselves warmly being welcomed by many Mons, led by Nai Maung Thaung, the son of late Mon leader, Nai Chit Thaung, who had arrived in Australia a long time ago. Among the Mons at the airport, they also met Ms Hazel Lang, whom he had known very well since 1993, when she involved in Mon refugee affairs and stayed in the Mon areas deep in the jungle. In order to honour them, the Mon community organised a welcoming reception at the Northbourne Flats, Canberra, where they met many Mons and friends of Mons.[2]

The first few days after their arrival were very busy them. They had to complete a lot of paperwork, go to Centrelink office, the bank, Medicare office and the Canberra Institute of Technology (CIT). As they had never heard about social security assistance from the government in Burma, the assistance provided by Centrelink in Australia was quite strange to them. The Burmese military junta had no sense of obligation when it comes to social welfare of the people. Instead, it only knew how to take from the people and never thought it also has an obligation to pay the public back something in return. He doesn't think any Burmese in Burma could understand what the term ‘governmental obligation’ really means to them.[2]

Life in oversea

The couple had to go an organisation called the Companion House (Red House as it was then known) for many medical check-ups. For the first time in his life he had such medical check-ups by experts without charge. They had to learn English at CIT and met with a lot of other students from various countries around the world who came here as refugees. He came to understand that there were many people like them who had to flee their home or countries and resettle in another country. They also came to realise that Australia is a multicultural society where every ethnic community can nurture its language and culture while freely practising their beliefs and religions.[2]

With the assistance of Nai Maung Thaung and other Mon friends everything went smoothly and within the first few days. All the paperwork had been done without any difficulty. He was very grateful to them for the assistance they rendered to him and his wife. For the first one-month they lived at Northbourne Flats with other Mon refugees before they moved to 28B, Currong Apartments, Braddon, ACT, a government-owned apartment building.[2]

As far as he could remember at that time some persons from the St Vincent de Paul Society came to visit them to provide necessities such as clothes and furniture. After two years of living in Australia, he and his wife applied for and were granted Australian citizenship. Both were very grateful to the Australian government for giving them new lives, new hope and for its social security assistance. In Australia he worked for the National Library of Australia briefly before retiring. In his retirement, he had learned about stock share trading and he was regarded an expert on share trading among the Mon community.[2]

Writer

Soon after his retirement, he started writing books on Mon politics, history and famous warriors including King Rajathirat in Burmese or English. He had written six books and was completing the seventh when passed away. He had been recognized as one of the prominent Mon writers at present. His proficiency in the Mon language appeared to have dissuaded him not to write books in Mon and it is his only known regret in his life.[2]

Personality and personal life

Despite his politics, he had never lost sight on meditation. He once remarked that meditation saved him from insanity when he was imprisoned in the Moulmein prison. After seeing his poor mental state, a fellow prisoner of a Chinese descent, took pity on him and taught him a meditation technique so that he could survive the prison system. Therefore, practicing meditation had been part of his life since then and he was always strict on maintaining his daily meditation sessions despite other family, community and social commitments.[2]

In turn of personality, he was gentle, courteous, thrift and unassuming. His gentle manner and soft-spoken style had been his signature trait that served him well among the Mon and other ethnic people during his revolutionary years and retirement. Those quality traits won over many admirers and friends wherever he went so it was not surprising that he has been one of the most respected elders and patrons of the Australia Mon Association and community leaders.[2]

Yet he could be a very stubborn man when it came to the Mon costume including its history and origin. His view on the current Mon costume especially on the male outfit was that it is a copy of the Burmese's, therefore, it does not fully reflect the Mon's traditional clothing. He had strongly argued that the Mon in the past wore some sort pants but not the saloon which was a latter adaptation either from the Burmese or Indian. Unsurprisingly, he had a lot of arguments with other Mons who have involved in creating the current Mon costume or others who see there is no need to recreate a different version of Mon male costume. He suggested we should look to Thai Mons and even Khmer when designing the Mon costume as theirs are much more reflective of or much more closer to the clothes that the Mon used to wear. Therefore, on many occasions, he was an odd man out among the crowd wearing a different outfit from others. In this regard, he had never wavered until he passed away.[2]

At advanced age, he found gardening fascinating. He spent hours for his garden in nurturing the seedlings, young and delicate plants so that they could survive the notorious Canberra winter and summer. Within his small garden, we can find several species of plants, flowers and trees ranging from lemon grasses, curry leaves, bay leaves, fig tree, orange, lemon, and various herbs, to different types of flowers. He was generous in sharing seasonal vegetables with community members and always happy to share his knowledge on horticulture too.[2]

Another hobby was making traditional medicines. According to his wife, he had collected many recipes on the traditional medicine. He also spent a lot of time in preparing and grinding various roots, leaves, flowers, fruits and bulks into powders to make the medicines. Again, he was very generous to share his ‘medicines’ for free to those who want to try or believe in the traditional medicines.[2]

Reception and legacy

Nai Pe Thein Zar, was a well-known and prominent Mon. He was a courageous student leader, a revolutionary and freedom fighter, an intellect, a writer, a true Mon gentleman and one of the most respected Mon elders and Mon community leaders in Australia. His contributions toward the Mon cause and dedications to our Mon community has been enormous. His passing is not only a great and unreplaceable loss to our Mon community here in Australia but to the whole community worldwide. If fact, we feel that we have lost a great guiding star and others also feel the same as well as. Tributes and condolences via phone calls, letters, and social media from individuals, various originations and communities around the world have been kept pouring in since his passing on Monday 30 July 2018.[2]

References

- Nai Pe Thein Zar (2016); Rājādhiraj, The King of Kings", Printed at Kyonemange Printing Services, Yangon, Publisher Mi Khaing Khaig Win (Su Su Mi - 00348, A short biography of author, p. back covered

- Australia Mon Association (2013) 'Mon Story Australia', Mon Office, Australia Mon Association Inc, Canberra, Australia.

- နိုင်ဖေသိန်းဇြာ၊ ဥက္ကဌကြီး နိုင်ရွှေကျင် နှင့် တော်လှန်ရေးသမား ဒို့မွန်ကျောင်းသား