Paternal depression

Paternal depression is a psychological disorder derived from parental depression. Paternal depression affects the mood of men; fathers and caregivers in particular. 'Father' may refer to the biological father, foster parent, social parent, step-parent or simply the carer of the child. This mood disorder exhibits symptoms similar to postpartum depression (PPD) including anxiety, insomnia, irritability, consistent breakdown and crying episodes, and low energy.[1] This may negatively impact family relationships and the upbringing of children.[2] Parents diagnosed with parental depression often experience increased stress and anxiety levels during early pregnancy, labor and postpartum.[2] Those with parental depression may have developed it early on but some are diagnosed later on from when the child is a toddler up until a young adult.

| Paternal depression | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Postpartum depression, Postnatal depression |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

| Symptoms | Anxiety, extreme sadness, substance abuse, irritability, violence, risky behavior, anger attacks |

| Complications | Relationships with partner and children |

| Usual onset | Early pregnancy to years postpartum |

| Causes | Unclear |

| Risk factors | Prior mental disorder and drug abuse, bipolar disorder, family history of depression, psychological stress, upholding multiple social roles, lack of support |

| Diagnostic method | Based on severity of symptoms |

| Differential diagnosis | Baby blues |

| Treatment | Counselling, medications, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) |

| Medication | Antidepressants |

The causes of paternal depression are unclear; however, previous experiences of mental disorders and family history can contribute to the development of paternal depression.[3] Other factors including stress overload, sleep deprivation and unhappy relationships with one's partner or children may also affect its prevalence.[4] Although symptoms of feeling down, baby blues and a lack of sleep are common amongst new parents, a diagnosis of depression is appropriate when symptoms are severe and ongoing.[5]

Most health literature provides studies and research on maternal depression and women with postnatal depression.[6] However, there is limited information about men and mental illness. Modern society and culture have changed social stigma of men with mental illness due to changes in gender role perspectives.[7]

Signs and symptoms compared to women

When comparing the anxiety level of first-time parents, women tend to have higher levels of anxiety. This is applicable to women immediately after birth and in the first three trimesters.[6] Compared to women, men experience greater anxiety levels within the first 3 months of childbirth and develop paternal depression as the children grows older.[5] Although depression can affect individuals in different ways, there are some gender differences between parents. Women tend to have similar depressive symptoms over all three trimesters, however in men, there are significant changes between the 1st and 2nd trimester, but not between the 2nd trimester to 3 months postpartum.[6] Women are also more likely to experience symptoms such as developing an eating disorder, irritability, crying episodes, extreme sadness, bipolar disorder and low energy levels.[8] Men are more likely to experience substance abuse, a higher frequency of irritability, anger attacks and becoming abusive and violent. Men may also partake in risk-taking behaviour such as drink driving. Despite common symptoms of loss of appetite and insomnia, women are more likely to display atypical behaviours such as oversleeping and overeating.[9] Fatal suicide attempts are also more often associated with fathers rather than with mothers.[10]

Causes

In general, the causes of maternal and paternal depression are similar. Common causes include having limited emotional and social support, experiencing financial stress, having an unsatisfying relationship with one's partner, finding difficulty adjusting to parenting, unexpected events in child development and personal histories of mental disorders and drug abuse.[3] According to a study conducted in 2005, 65% of males identified with depressive symptoms when the child was 8 weeks old.[4] The causes of paternal depression include stress overload, caring responsively to the children, undertaking multiple family and social roles and a decrease in direct father to child interaction.[4] Fathers of young boys are most vulnerable to paternal depression during the child's early and behavioural development. This is caused by young boys having the tendency to be hyperactive and harder to discipline.[4] This causes the father to be concerned and frustrated. There is a positive correlation between a boy's misbehaviour and depression in fathers.[4]

Prevalence

Men in the U.S.

Studies show that 14.1% of men suffer from postpartum depression.[11] Outside of the U.S. 8.2% of men experience depressive symptoms. The observation of postpartum depression could be categorised into the time blocks of paternal depression: first trimester to 6 months gestational age, >6 months to birth, immediate postpartum to 3 months postpartum, >3 to 6 months postpartum and >6 to 12 months postpartum.[11] During the period of 3 to 6 months postpartum, the highest rate of 25.6% was recorded in men whilst the lowest occurred during the first three months of postpartum at 7.7%. The high levels of depression during the 3 to 6 months postpartum period is also similar amongst women.[11] These results could be explained by the strenuousness of 3 to 6 months newborn care.

Treatment

Treatment for paternal depression depends on the severity of it.[5] Light to moderate symptoms could be treated at home. This includes being well-rested, getting alone time, eating a well-balanced diet with adequate amounts of water and exercise, accepting social support from partner, friends and family.[12] Joining local community groups and creating bonds with other fathers experiencing similar symptoms will decrease stress and create a sense of relief. However, treatment of mild to severe depression would require further action.

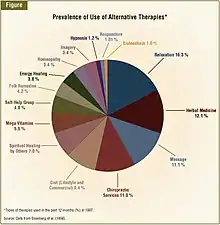

Treatments offered for parents with depression are similar to other mental disorders. This includes taking antidepressants or receiving psychotherapy.[15] Those experiencing moderate paternal depression should seek therapy from a mental health professional. This may be a psychiatrist, counselor or psychologist. However, if experiencing intense depression, medical intervention may be necessary.[16] Consult your health professional about medication including mood stabilizers. Other methods to recovery include electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).[17] This releases short electrical currents to the brain, allowing it to relax. It is recommended when all other procedures are ineffective. There are other alternatives to treatment. This includes self-care in the form of relaxation, massage, herbal medicine and chiropractic services.[14]

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy aids PPD treatment by approaching it with psychological, rather than biological, intervention.[18] Many parents with PPD prefer psychological treatment as it limits any potential side affects that will influence the child. Common therapy styles include interpersonal therapy, cognitive-behavioural therapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy and non-directive counseling.[19] Therapy could be conducted individually or couple therapy is also an option. This is practical in addressing support at home along with your relationship with your partner.[20] In general, therapy may take anywhere between a few weeks to months to be effective. However, severe symptoms will require intense psychotherapy which may take up to years.[18]

Antidepressants

Pharmacological treatment such as antidepressant medication is a growing method of treatment with a recent increase in literature surrounding the topic.[21][22] This is given to those that experience severe PPD as it balances the chemicals in the brain that affect mood.[23] Mothers tend to avoid antidepressants with many fearing its impact on breast milk.[19][24] However, it is an effective way in treating depression amongst fathers. There are several factors that the father may want to consider; this includes metabolic changes, mood changes, memory loss, drowsiness and possible side effects influencing child care. Medication needs to be under the supervision of a medical professional and is proven to be even more effective when accompanied with psychotherapy.[20]

Self-care

There are a number of ways to treat PPD at home. These methods are recommended for those with moderate PPD. However, severe PPD will require intensive intervention. The following practices will promote a healthier and positive lifestyle and are beneficial to anyone: talking to loved ones, taking alone time, getting sufficient amounts of rest, exercising regularly and eating a balanced diet.[24] Not skipping meals, prioritising sleep and getting outside will improve mental health and increase feelings of satisfaction and fulfilment.[20]

Society and culture

The increase of paternal depression could be explained by women's increasing input into social roles.[25] Women contributing to the workforce leads to more fathers becoming involved with family life. This increases the possibility of developing paternal depression. Paternal depression is a frequently neglected topic.[16] It challenges social normalities of gender roles, the stereotypes of fatherhood, masculinity and social stigma on men with mental health.[25] The progressive perception of fathers being the primary parent leads to further increase in father involvement.

National policies have not progressed with the changes in gender roles. This includes the difficulties in receiving of paternal leave and receiving custody.[26] This is influenced by the limited studies on fathers and depression. However, the recent increase of research into paternal depression shows society's views on increasing gender equality in social roles and the changing culture on masculine and feminine concepts.[7]

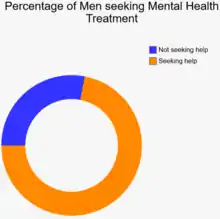

Stigma of men with mental illness

There is often stigma around mental illness, especially for men. Severe stigma usually takes forms of discrimination, prejudice and stereotypes. These categorise how society view mental disorders. Paired with gender roles and the concepts of masculinity and femininity, society views men with mental impairments as weak and vulnerable and not the stereotypical alpha male.[7] This then affects how men view their own mental disability, influencing the seeking of treatment and acceptance of the illness.[16] This cause and effect relationship can create a cycle, leading men to be disheartened and ashamed of reaching out. According to the Australian Black Dog Institute, it is estimated that 72% of men do not seek treatment for mental disorders.[27]

References

- Mickelson KD, Biehle SN, Chong A, Gordon A (2017-03-01). "Perceived Stigma of Postpartum Depression Symptoms in Low-Risk First-Time Parents: Gender Differences in a Dual-Pathway Model". Sex Roles. 76 (5): 306–318. doi:10.1007/s11199-016-0603-4. S2CID 147479681.

- Delrosario, G. A.; Chang, A. C.; Lee, E. D. (2013). "Wolters Kluwer Health - Article Landing Page". JAAPA. 26 (2): 50–4. doi:10.1097/01720610-201302000-00009. PMID 23409386. S2CID 7842384. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- "beyondblue". www.beyondblue.org.au. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Ramchandani P, Stein A, Evans J, O'Connor TG (2005-06-25). "Paternal depression in the postnatal period and child development: a prospective population study". Lancet. 365 (9478): 2201–5. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66778-5. PMID 15978928. S2CID 34516133.

- Kanopy (Firm), Recognizing and treating postpartum depression., OCLC 897768040

- Figueiredo B, Conde A (July 2011). "Anxiety and depression symptoms in women and men from early pregnancy to 3-months postpartum: parity differences and effects". Journal of Affective Disorders. 132 (1–2): 146–57. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.02.007. hdl:1822/41604. PMID 21420178.

- Boysen GA (2017-01-02). "Exploring the relation between masculinity and mental illness stigma using the stereotype content model and BIAS map". The Journal of Social Psychology. 157 (1): 98–113. doi:10.1080/00224545.2016.1181600. PMID 27110638. S2CID 13093367.

- Nierenberg, Cari; October 27, Contributing writer; ET, 2016 03:22am. "7 Ways Depression Differs in Men and Women". Live Science. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Silverstein B, Angst J (2015). "Evidence for Broadening Criteria for Atypical Depression Which May Define a Reactive Depressive Disorder". Psychiatry Journal. 2015: 575931. doi:10.1155/2015/575931. PMC 4516843. PMID 26258131.

- England MJ, Sim LJ, editors (2009). Depression in Parents, Parenting, and Children : Opportunities to Improve Identification, Treatment, and Prevention. National Academies Press (US). OCLC 971082452.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Bond S (September 2010). "Men suffer from prenatal and postpartum depression, too; rates correlate with maternal depression". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 55 (5): e65-6. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2010.06.015. PMID 20732656.

- "Postpartum Depression: A Guide to Symptoms & Treatment". PsyCom.net - Mental Health Treatment Resource Since 1986. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- "Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a follow-up national survey". Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 7 (3): 191–192. 1990–1999. doi:10.1016/s0965-2299(99)80132-0. ISSN 0965-2299.

- Hendrick, Victoria (August 2003). "Alternative Treatments for Postpartum Depression". Psychiatric Times.

- "Postpartum depression - Diagnosis and treatment - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- Cameron EE, Hunter D, Sedov ID, Tomfohr-Madsen LM (June 2017). "What do dads want? Treatment preferences for paternal postpartum depression". Journal of Affective Disorders. 215: 62–70. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2017.03.031. PMID 28319693.

- Verwijk E, Comijs HC, Kok RM, Spaans HP, Stek ML, Scherder EJ (November 2012). "Neurocognitive effects after brief pulse and ultrabrief pulse unilateral electroconvulsive therapy for major depression: a review". Journal of Affective Disorders. 140 (3): 233–43. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.024. PMID 22595374.

- "Postpartum Depression Treatment, Screening, Causes & Symptoms". MedicineNet. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Fitelson E, Kim S, Baker AS, Leight K (December 2010). "Treatment of postpartum depression: clinical, psychological and pharmacological options". International Journal of Women's Health. 3: 1–14. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S6938. PMC 3039003. PMID 21339932.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Melinda (2018-11-02). "Postpartum Depression and the Baby Blues - HelpGuide.org". Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Payne JL (September 2007). "Antidepressant use in the postpartum period: practical considerations". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (9): 1329–32. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030390. PMID 17728416.

- Battle CL, Zlotnick C, Pearlstein T, Miller IW, Howard M, Salisbury A, Stroud L (2008–2010). "Depression and breastfeeding: which postpartum patients take antidepressant medications?". Depression and Anxiety. 25 (10): 888–91. doi:10.1002/da.20299. PMC 3918906. PMID 17431885.

- "Postpartum depression: Symptoms, causes, and diagnosis". Medical News Today. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- "Treatment". nhs.uk. 2018-10-03. Retrieved 2019-05-27.

- Fisher SD (2016-02-16). "Paternal Mental Health: Why Is It Relevant?". American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 11 (3): 200–211. doi:10.1177/1559827616629895. PMC 6125083. PMID 30202331.

- Qadar, By Sana (2019-05-05). "Three fathers' experiences taking parental leave - ABC Life". www.abc.net.au. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Australia. Department of Health and Ageing. Australia. Department of Health and Ageing. Health Priorities and Suicide Prevention Branch. (2013). National mental health report 2013 : tracking progress of mental health reform in Australia, 1993-2011. Dept. of Health and Ageing. ISBN 9781742419251. OCLC 948775488.