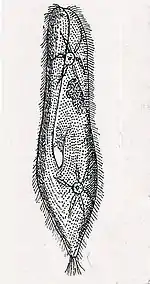

Paramecium caudatum

Paramecium caudatum[1] is a species of unicellular protist in the phylum Ciliophora.[2] They can reach 0.33 mm in length and are covered with minute hair-like organelles called cilia.[3] The cilia are used in locomotion and feeding.[2] The species is very common, and widespread in marine, brackish and freshwater environments.[4][5]

| Paramecium caudatum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Clade: | SAR |

| Infrakingdom: | Alveolata |

| Phylum: | Ciliophora |

| Class: | Oligohymenophorea |

| Order: | Peniculida |

| Family: | Parameciidae |

| Genus: | Paramecium |

| Species: | P. caudatum |

| Binomial name | |

| Paramecium caudatum | |

Appearance and physical characteristics

Paramecium caudatum is 170–330 micrometres long (usually 200–300 micrometres).[6] The cell body is spindle-shaped, rounded at the front, tapering at the posterior to a blunt point. Early microscopists likened its shape to that of a slipper, and commonly referred to it as the "slipper animalcule."[7] The pellicle is uniformly covered with cilia, and has a long oral groove, leading to deeply embedded oral cavity, lined with cilia (short, hair-like protoplasmic processes that serve as organs of locomotion and food capture). P. caudatum has two contractile vacuoles, which serve to excrete excess water taken up from the outside, regulating the water contents of the body. Radially distributed "collecting canals" give the contractile vacuoles a distinctive star-like shape.[8][7] The cell is enclosed by a cellular envelope (cortex) densely studded with spindle-shaped extrusomes called trichocysts.[4][5]

P. caudatum feed on bacteria and small eukaryotic cells, such as yeast and flagellate algae.[2] the accumulated food particles, at the posterior end of the cytopharynx, are directed by the long cilia into the rounded, ball-like mass in the endoplasm called food vacuole. The food vacuoles are circulated by the streaming movement of the endoplasm which is called cyclosis. In hypotonic conditions (freshwater), the cell absorbs water by osmosis. It regulates osmotic pressure with the help of bladder-like contractile vacuoles, gathering internal water through its star-shaped radial canals and expelling the excess through the plasma membrane.[3] When moving through the water, they follow a spiral path while rotating on the long axis.[2]

Paramecium have two nuclei (a large macronucleus and a single compact micronucleus).[9] They cannot survive without the macronucleus and cannot reproduce without the micronucleus.[3] Like all ciliates, Paramecia reproduce asexually, by binary fission. During reproduction, the macronucleus splits by a type of amitosis, and the micronuclei undergo mitosis. The cell then divides transversally, and each new cell obtains a copy of the micronucleus and the macronucleus.[10]

Fission may occur as part of the normal vegetative cell cycle. Under certain conditions, it may be preceded by self-fertilization (autogamy),[11] or it may follow conjugation, a sexual phenomenon in which Paramecia of compatible mating types fuse temporarily and exchange genetic material. During conjugation, the micronuclei of each conjugant divide by meiosis and the haploid gametes pass from one cell to the other. The gametes of each organism then fuse to form diploid micronuclei. The old macronuclei are destroyed, and new ones are developed from the new micronuclei.[12]

Without the rejuvenating effects of autogamy or conjugation a Paramecium ages and dies.[3] Only opposite mating types, or genetically compatible organisms, can unite in conjugation.[3]

References

- "Paramecium caudatum". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- 101 Science.com: Paramecium Caudatum

- Paramacium

- Carey, Philip G. Marine interstitial ciliates: an illustrated key. 1992. p. 128

- "Paramecium caudatum". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 2013-02-14.

- FOISSNER Wilhelm; BERGER Helmut & KOHMANN Fritz (1994). Taxonomische und ökologische Revision der Ciliaten des Saprobiensystems. Band III: Hymenostomata, Prostomatida, Nassulida. Informationsberichte des Bayerischen Landesamtes für Wasserwirtschaft. p. 112.

- Wichterman, R. (2012-12-06). The Biology of Paramecium. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 38. ISBN 978-1-4757-0372-6.

- Patterson, D. J. (1980). "Contractile Vacuoles and Associated Structures: Their Organization and Function". Biological Reviews. 55 (1): 3. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1980.tb00686.x. ISSN 1469-185X.

- "Paramecium". Microbus. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Lynn, Denis. The ciliated protozoa: characterization, classification, and guide to the literature. Springer, 2010. 279.

- Berger, James D. "Autogamy in Paramecium cell cycle stage-specific commitment to meiosis." Experimental cell research 166.2 (1986): 475–485.

- Prescott, D. M., et al. "DNA of ciliated protozoa." Chromosome 34.4 (1971): 355–366.