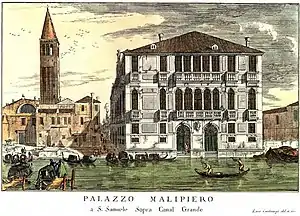

Palazzo Malipiero

Palazzo Malipiero is a palace in Venice, Italy. It is on the Grand Canal in the central San Samuele square. It stands just across from the Palazzo Grassi Exhibition Center.

It is situated at the crossroads of the city's cultural and artistic areas. The splendid Italian-style garden with a view of the Grand Canal makes it even more unique.

Originally built in Byzantine times, the nine centuries' architectural history of the palace can be retraced in its complex structure: each generation of owners left its stamp of caring and fervour for the arts.

For some years from 1740 Giacomo Casanova lived in the Palazzo Malipiero. In spite of his young age (he was just 15 years old), he began his successful social life in these very rooms. Here he gave a broad demonstration of his innate gift for the art of love.

The present owners have handled the recent restoration with special care in respecting the palace's historical background. They have maintained Palazzo Malipiero's ancient splendour and the traditional prestige, and, in upgrading installations and equipment to modern standards, improved the great comfort of its spacious rooms.

History

The Ca' Grande (big palace) of Saint Samuel was probably built at the beginning of the 11th century by the Soranzo family, which also built in that period, together with the Boldù family, the church of St. Samuel facing the Palace. In the 13th century a floor was added to the pre-existing bizantyne style' building, in accordance with the custom at the time.

In the early days of the 15th century the Cappello family, one of the most energetic and industrious families of Venice, became owners of the Palace as a result of marriages with the Soranzos. As from the mid-16th century the Cappello enlarged the building and conferred to the facade on the Grand Canal its present shape.

Around the 1590 the Malipiero family became tenants of the Cappellos and Caterino Malipiero, within few years as from 1610, through the marriage with Elisabetta Cappello and further purchases, obtained ownership of the whole edifice. Evidence of the very many restorations done by him are the date 1622 and the initials K.M. -Caterino Malipiero- in an engraving placed over on the main door he built, giving access to the new large entrance of the Palace.

Around the year 1725, the Malipiero began new massive restoration works that gave the palace today's homogeneous aspect. In the first half of the 19th century, with the Venetian Republic in full decline and after four centuries of successions, the Palace of the Soranzos, Cappellos and Malipieros suffered the same destiny as many other palaces of Venetian patrician families: passing from hand to hand as a result of many transfers.

These transfers accelerated the decline of the building until the Barnabò family purchased it, who in [1951]] undertook a substantial restoration returning the palace premises to a grand and serene eighteenth-century style.

Giacomo Casanova and the Malipiero's

Very little information could be collected as to the events that took place in the Palace. However, it appears that the Cappello family put the palace's storehouses to good use by developing the newly discovered printing and publishing activity there.

What we know is that between 1656 and 1676, as a result of the construction of two very popular and successful theatres, a licentious way of life spread all over St. Samuel parish, and soon infected the palace.

We also know that Giacomo Casanova, who was born on the Calle della Commedia (later renamed the Calle Malipiero), from 1740 frequented the Palazzo Malipiero assiduously, as a confidant of Senator Alvise II "Gasparo" Malipiero.

Here he established relationships with some influential persons and with a great many ladies. But one day the Senator caught him with Teresa Imer, on whom the Senator himself had invested some illusions, and Casanova was expelled from the Palace and later from Venice.

Casanova left a lively portrait of Alvise II in his Memoires. The latter work is historically meaningful due to its portrait of the Venetian custom in the 18th century. In this bizarre and turbulent environment, the Malipiero suffered a passive decadent demise.

St. Samuel parish cultural life was revived only after 1950 when the Palazzo Grassi Cultural Center was established. The Palazzo Malipiero also contributes to Venice's Cultural heritage revival by hosting the exhibition spaces of Studio d'Arte Barnabò Gallery and Il Tridente multimedia publishing house.

Evolution

As with most Venetian palaces, the Cà Grande (Great House) of Saint Samuel is built as two main superposed floors, but unlike other palaces, each floor is accessed by its own independent entrance hall, stairway and porta d'acqua (water door).

Through an ancient Byzantine door one accesses the "secondo piano nobile" (second main floor). The main door opens onto a large seventeenth century entrance hall leading to the magnificent "primo piano nobile" (first main floor) and to the ancient medieval court-yard, the19th century garden and the door on the Grand Canal.

The architectural development of the "Cà Grande di San Samuele" is similar to the traditional evolution of many Venetian palaces, the freedom and the harmony of structures underpinning the vivid rhythms and original fascination of the city. In fact the structure of the building is made of three parts, each closely merged to the others, representing three eras: the Byzantine style, the International Gothic style and the seventeenth century one.

The original part of the building was probably built between the 10th and 11th centuries by Soranzo family in Venetian-Byzantine style, as evidenced by the large door (number 3201) and the quadruple windows with round arches (later amalgamated into the gothic structure) visible on the San Samuele side. In the middle of the 14th century, the Soranzo added a second floor to the Cà Grande, as evidenced by the pointed arch windows.

This Gothic design was perfectly amalgamated with the floor below, respecting and incorporating elements of the Byzantine construction. By the mid-15th century the Cappello decided to expand the palace, too narrow at the time. Building on an unused area on the garden's side, the facade on the Grand Canal was widened to the dimensions we enjoy today.

Restoring and enlarging the building was also the main concern of Caterino Malipiero, as testified by the date 1622 and initials K.M. (Caterino Malipiero) engraved on the main door accessing the large Palace entrance. The family's coat-of-arms with cock's claws is also proudly sculpted there. In the second half of the seventeenth century, Palazzo Malipiero, its architecture ignoring Baroque, was one of the richest and most meaningful buildings in Venice.

In the first half of 18th century the Malipiero family, in accordance with an architectural project now lost, decided to enlarge their Palace connecting it with some houses abutting it on its rear, eliminating the Calle Malipiero that separated them. The facade on Campo San Samuele was extended backwards by 30 meters; the garden was widened to include part of a pre-existing Ramo Malipiero which bordered the Palace on the garden side, and a new perspective was created from the Palace's main entrance to the garden.

This can be easily seen on the drawing of 1718 by Luca Carlevarjs and reproduced in the site home page. On it the palace ended after the two main entrances and a Calle borders its back end and separates it from the other houses that now are part of the building. The drawing clearly depicts further back the Calle della Commedia where Giacomo Casanova was born, and which was later renamed Calle Malipiero.

During the 19th century the venerable Cà Grande of the Soranzos, Cappellos and Malipieros was neglected but kept intact in its seventeenth-century structure; and it was only at the beginning of the 20th century that the palace saw some restoration. Then, in the early 1950s the Barnabò family started a complete renovation project. The works, directed by Nino Barbantini, restored the ancient charm to the palace, its interior and to the garden.

Garden

The garden of Palazzo Malipiero was created, together with many others, at the end of the eighteenth century, when the large palace gardens situated on the outskirts of the city disappeared because of residential and industrial development.

No doubt due to the particularities of the building plan, with a large entrance hall connecting Campo San Samuele to the courtyard, the garden's layout is most original: the area, compartmented by a simple design of hedge lines, extends along the building and is aligned both on the courtyard and the Grand Canal.

Thus the garden, when viewed from the Grand Canal, is divided in two symmetrical parts centred around a Hercule's Nymph fountain. The latter is also aligned with the 17th century entrance hall, so that a perspective view can be seen when entering the palace from the main door, through to the fountain, a statue of Neptune inserted in the opposite garden wall.

In the garden has been placed the large well (originally in the inner courtyard) that, with the family coat-of-arms and the sculpted figures of the bride and bridegroom Elisabetta e Caterino, bear witness to the union between the Cappellos and the Malipieros.

From the end of 19th century, a number of statues have contributed to enrich the garden landscaping. The hedge, thanks to its intense colouring and precise pruning, conveys a further sophisticated touch to this precious garden.

See also

- List of architecture monuments of Venice

External links

Bibliography

- Giovanni Dolcetti, Alvise De Michelis, Le vicende storiche dell'antico Palazzo Soranzo (poi Cappello, Malipiero e Barnabò) a S. Samuele (Venice, 2007)

- Maria Cunico, Il giardino veneziano: la storia, l`architettura, la botanica (Venice, 1989)

- Elena Bassi, Palazzi di Venezia (Venice, 1976)

- Gino Damerini, La Ca` Grande dei Cappello e dei Malipiero di San Samuele ora Barnabò (Venice, 1962)

- Giuseppe Lorenzetti, Venezia e il suo estuario, guida storico-artistica, (Venice, 1926)

- Giacomo Casanova, Histoire de ma vie (published posthumously, 1822–1828)