Old Nubian

Old Nubian (also called Middle Nubian or Old Nobiin) is an extinct Nubian language, attested in writing from the 8th to the 15th century AD. It is ancestral to modern-day Nobiin and closely related to Dongolawi and Kenzi. It was used throughout the kingdom of Makuria, including the eparchy of Nobatia. The language is preserved in more than a hundred pages of documents and inscriptions, both of a religious (homilies, prayers, hagiographies, psalms, lectionaries), and related to the state and private life (legal documents, letters), written using an adaptation of the Coptic alphabet.

| Old Nubian | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Egypt, Sudan |

| Region | Along the banks of the Nile in Lower and Upper Nubia (southern Egypt and northern Sudan) |

| Era | 8th–15th century; evolved into Nobiin. |

Nilo-Saharan?

| |

| Nubian | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | onw |

onw | |

| Glottolog | oldn1245 |

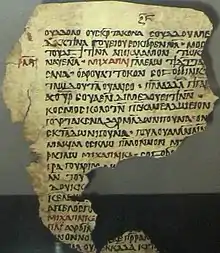

A page from an Old Nubian translation of the Investiture of the Archangel Michael, from the 9th-10th century, found at Qasr Ibrim, now at the British Museum. Michael's name appears in red with a characteristic epenthetic -ⲓ. | |

History

Old Nubian had its source in the languages of the Noba nomads who occupied the Nile between the first and third cataracts of the Nile and the Makurian nomads who occupied the land between the third and fourth cataracts following the collapse of Meroë sometime in the 4th century. The Makurians were a separate tribe who eventually conquered or inherited the lands of the Noba: they established a Byzantine-influenced state called Makuria which administered the Noba lands separately as the eparchy of Nobatia. Nobatia was converted to the Miaphysite Christianity by Julian of Halicarnassus and Longinus, and thereafter received its bishops from the Pope of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.[1]

Old Nubian is one of the oldest written African languages and appears to have been adopted from the 10th–11th century as the main language for the civil and religious administration of Makuria. Besides Old Nubian, Koine Greek was widely used, especially in religious contexts, while Coptic mainly predominates in funerary inscriptions.[2] Over time, more and more Old Nubian began to appear in both secular and religious documents (including the Bible), while several grammatical aspects of Greek, including the case, agreement, gender, and tense morphology underwent significant erosion.[3] The consecration documents found with the remains of archbishop Timotheos suggest, however, that Greek and Coptic continued to be used into the late 14th century, by which time Arabic was also in widespread use.

Writing

The script in which nearly all Old Nubian texts have been written is a slanted uncial variant of the Coptic alphabet, originating from the White Monastery in Sohag.[4] The alphabet included three additional letters ⳡ /ɲ/ and ⳣ /w/, and ⳟ /ŋ/, the first two deriving from the Meroitic alphabet. The presence of these characters suggest that although the first written evidence of Old Nubian dates to the 8th century, the script must have already been developed in the 6th century, following the collapse of the Meroitic state.[5] Additionally, Old Nubian used the variant ⳝ for the Coptic letter ϭ.

| Character | ⲁ | ⲃ | ⲅ | ⲇ | ⲉ | ⲍ | ⲏ | ⲑ | ⲓ | ⲕ | ⲗ | ⲙ | ⲛ | ⲝ/ϩ̄ | ⲟ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transliteration | a | b | g | d | e | z | ē | th | i | k | l | m | n | x | o |

| Phonetic value | /a, aː/ | /b/ | /ɡ/ | /d/ | /e, eː/ | /z/ | /i, iː/ | /t/ | /i/ | /k, ɡ/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ | /ks/ | /o, oː/ |

| Character | ⲡ | ⲣ | ⲥ | ⲧ | ⲩ | ⲫ | ⲭ | ⲯ | ⲱ | ϣ | ϩ | ⳝ | ⳟ | ⳡ | ⳣ |

| Transliteration | p | r | s | t | u | ph | kh | ps | ō | š | h | j | ŋ | ñ | w |

| Phonetic value | /p/ | /ɾ/ | /s/ | /t/ | /i, u/ | /f/ | /x/ | /ps/ | /o, oː/ | /ʃ/ | /h/ | /ɟ/ | /ŋ/ | /ɲ/ | /w/ |

The characters ⲍ, ⲝ/ϩ̄, ⲭ, ⲯ only appear in Greek loanwords. Gemination was indicated by writing double consonants; long vowels were usually not distinguished from short ones. Old Nubian featured two digraphs: ⲟⲩ /u, uː/ and ⲉⲓ /i, iː/. A diaeresis over ⲓ (ⲓ̈) was used to indicate the semivowel /j/. In addition, Old Nubian featured a supralinear stroke, which could indicate:

- a vowel that formed the beginning of a syllable or was preceded by ⲗ, ⲛ, ⲣ, ⳝ;

- an /i/ preceding a consonant.

Modern Nobiin is a tonal language; if Old Nubian was tonal as well, the tones were not marked.

Punctuation marks included a high dot •, sometimes substituted by a double backslash \\ (⳹), which was used roughly like an English period or colon; a slash / (⳺), which was used like a question mark; and a double slash // (⳼), which was sometimes used to separate verses.

Grammar

Nouns

Old Nubian has no gender. The noun consists of a stem to which derivational suffixes may be added. Plural markers, case markers, postpositions, and the determiner are added on the entire noun phrase, which may also comprise adjectives, possessors, and relative clauses.

Determination

Old Nubian has one definite determiner -(ⲓ)ⲗ.[6] The precise function of this morpheme has been a matter of controversy, with some scholars proposing it as nominative case or subjective marker. Both the distribution of the morpheme and comparative evidence from Meroitic, however, point to a use as determiner.[7][8]

Case

Old Nubian has a nominative-accusative case system with four structural cases determining the core arguments in the sentence,[9] as well as a number of lexical cases for adverbial phrases.

| Structural Cases | Nominative | – |

|---|---|---|

| Accusative | -ⲕ(ⲁ) | |

| Genitive | -ⲛ(ⲁ) | |

| Dative | -ⲗⲁ | |

| Lexical Cases | Locative | -ⲗⲟ |

| Allative | -ⲅⲗ̄(ⲗⲉ) | |

| Superessive | -ⲇⲟ | |

| Subessive | -ⲇⲟⲛ | |

| Comitative | -ⲇⲁⲗ | |

Number

The most common plural marker is -ⲅⲟⲩ, which always precedes case marking. There are a few irregular plurals, such as ⲉⲓⲧ, pl. ⲉⲓ "man"; ⲧⲟⲧ, pl. ⲧⲟⲩⳡ "child." Furthermore, there are traces of separate animate plural forms in -ⲣⲓ, which are textually limited to a few roots, e.g. ⲭⲣⲓⲥⲧⲓⲁ̄ⲛⲟⲥ-ⲣⲓ-ⲅⲟⲩ "Christians"; ⲙⲟⲩⲅ-ⲣⲓ-ⲅⲟⲩ "dogs."

Pronouns

Old Nubian has several sets of pronouns and subject clitics[10] are the following, of which the following are the main ones:

| Person | Independent Pronoun | Subject Clitic |

|---|---|---|

| I | ⲁⲓ̈ | -ⲓ |

| you (sg.) | ⲉⲓⲣ | -ⲛ |

| he/she/it | ⲧⲁⲣ | -ⲛ |

| we (including you) | ⲉⲣ | -ⲟⲩ |

| we (excluding you) | ⲟⲩ | -ⲟⲩ |

| you (pl.) | ⲟⲩⲣ | -ⲟⲩ |

| they | ⲧⲉⲣ | -ⲁⲛ |

There are two demonstrative pronouns: ⲉⲓⲛ, pl. ⲉⲓⲛ-ⲛ̄-ⲅⲟⲩ "this" and ⲙⲁⲛ, pl. ⲙⲁⲛ-ⲛ̄-ⲅⲟⲩ "that." Interrogative words include ⳟⲁⲉⲓ "who?"; ⲙⲛ̄ "what?"; and a series of question words based on the root ⲥ̄.

Verbs

The Old Nubian verbal system is by far the most complex part of its grammar, allowing for valency, tense, mood, aspect, person and pluractionality to be expressed on it through a variety of suffixes.

The main distinction between nominal and verbal predicates in a main clause versus a subordinate clause is indicated by the presence of the predicate marker -ⲁ.[11] The major categories, listing from the root of the verb to the right, are as follows:

Valency

| Transitive | -ⲁⲣ |

|---|---|

| Causative | -ⲅⲁⲣ |

| Inchoative | -ⲁⳟ |

| Passive | -ⲧⲁⲕ |

Pluractionality

| Pluractional | -ⳝ |

|---|---|

Aspect

| Perfective | -ⲉ |

|---|---|

| Habitual | -ⲕ |

| Intentional | -ⲁⲇ |

Tense

| Present | -ⲗ |

|---|---|

| Past 1 | -ⲟⲗ |

| Past 2 | -ⲥ |

Person

This can be indicated by a three different series of subject clitics, which are obligatory only in certain grammatical contexts.

Sample text

- P.QI 1 4.ii.25 ⲕⲧ̅ⲕⲁ ⲅⲉⲗⲅⲉⲗⲟ̅ⲥⲟⲩⲁⲛⲛⲟⲛ ⲓ̈ⲏ̅ⲥⲟⲩⲥⲓ ⲙⲁⳡⲁⲛ ⲧⲣⲓⲕⲁ· ⲇⲟⲗⲗⲉ ⲡⲟⲗⲅⲁⲣⲁ [ⲡⲉⲥⲥⲛⲁ·] ⲡⲁⲡⲟ ⲥ̅ⲕⲉⲗⲙ̅ⲙⲉ ⲉⲕ̅[ⲕⲁ]

- kit-ka gelgel-os-ou-an-non iēsousi mañan tri-ka dolle polgar-a pes-s-n-a pap-o iskel-im-m-e eik-ka

- stone-ACC roll-PFV-PST1-3PL-TOP Jesus eye.DU both-ACC high raise.CAUS-PRED speak-PST2-2/3/SG-PRED father-VOC thank-AFF-PRS-1SG.PRED you-ACC

"And when they rolled away the rock, Jesus raised his eyes high and said: Father, I thank you."

Notes

- Hatke, George (2013). Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa. NYU Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-8147-6283-7.

- Ochała 2014, pp. 44–45.

- Burstein 2006.

- Boud'hors 1997.

- Rilly 2008, p. 198.

- Zyhlarz 1928, p. 34.

- Van Gerven Oei 2011, pp. 256–262.

- Rilly 2010, p. 385.

- Van Gerven Oei 2014, pp. 170–174.

- Van Gerven Oei 2018.

- Van Gerven Oei 2015.

References

- Boud'hors, Anne (1997). "L'onciale penchée en copte et sa survie jusqu'au XVe siècle en Haute-Égypte". In Déroche, François; Richard, Francis (eds.). Scribes et manuscrits du Moyen-Orient. Paris: Bibliothèque nationale de France. pp. 118–133.

- Burstein, Stanley (2006). When Greek was an African Language (Speech). Third Annual Snowden Lecture. Harvard University. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Van Gerven Oei, Vincent W.J. (2011). "The Old Nubian Memorial for King George". In Łajtar, Adam; Van der Vliet, Jacques (eds.). Nubian Voices: Studies in Nubian Culture. The Journal of Juristic Papyrology Supplements XV. Warsaw: Raphael Taubenschlag Foundation. pp. 225–262.

- Van Gerven Oei, Vincent W.J. (2014). "Remarks toward a Revised Grammar of Old Nubian". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 1: 165–184. doi:10.5070/d61110015. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Van Gerven Oei, Vincent W.J. (2015). "A Note on the Old Nubian Morpheme -a in Nominal and Verbal Predicates". In Łajtar, Adam; Ochała, Grzegorz; Van der Vliet, Jacques (eds.). Nubian Voices II: New Texts and Studies on Christian Nubian Culture. The Journal of Juristic Papyrology Supplements XXVII. Warsaw: Raphael Taubenschlag Foundation. pp. 313–334. doi:10.17613/M64T11. ISBN 978-83-938425-7-5.

- Van Gerven Oei, Vincent W.J. (2018). "Subject Clitics: New Evidence from Old Nubian". Glossa. 3 (1). doi:10.5334/gjgl.503.

- Ochała, Grzegorz (2014). "Multilingualism in Christian Nubia: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. 1: 1–50. doi:10.5070/d61110007. Retrieved June 19, 2018.

- Rilly, Claude (2008). "The Last Traces of Meroitic? A Tentative Scenario for the Disappearance of the Meroitic Script". In Baines, John; Bennet, John; Houston, Stephen (eds.). The Disappearance of Writing Systems: Perspectives on Literacy and Communication. London: Equinox Publishing. pp. 183–205.

- Rilly, Claude (2010). Le méroïtique et sa famille linguistique. Afrique et Langage 14. Leuven: Peeters.

- Zyhlarz, Ernst (1928). Grundzüge der nubischen Grammatik im christlichen Frühmittelalter (Altnubisch): Grammatik, Texte, Kommentar und Glossar. Leipzig: Deutsche Morgenländische Gesellschaft.

Other sources

- Browne, Gerald M., (1982) Griffith's Old Nubian Lectionary. Rome / Barcelona.

- Browne, Gerald M., (1988) Old Nubian Texts from Qasr Ibrim I (with J. M. Plumley), London, UK.

- Browne, Gerald M., (1989) Old Nubian Texts from Qasr Ibrim II. London, UK.

- Browne, Gerald M., (1996) Old Nubian dictionary. Corpus scriptorum Christianorum orientalium, vol. 562. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 90-6831-787-3.

- Browne, Gerald M., (1997) Old Nubian dictionary - appendices. Leuven: Peeters. ISBN 90-6831-925-6.

- Browne, Gerald M., (2002) A grammar of Old Nubian. Munich: LINCOM. ISBN 3-89586-893-0.

- Griffith, F. Ll., (1913) The Nubian Texts of the Christian Period. ADAW 8. https://archive.org/details/nubiantextsofchr00grif

- Satzinger, Helmut, (1990) Relativsatz und Thematisierung im Altnubischen. Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 80, 185–205.

External links

- Extended details on all the letters of the Old Nubian alphabet, especially the additional ones, can be found in this Unicode proposal by Michael Everson and Stephen Emmel.

- The Basic Languages of Christian Nubia: Greek, Coptic, Old Nubian, and Arabic. Ancient Sudan website.

- Old Nubian basic lexicon at the Global Lexicostatistical Database