Oil pastel

An oil pastel is a painting and drawing medium formed into a stick which consists of pigment mixed with a binder mixture of non-drying oil and wax, in contrast to other pastel sticks which are made with a gum or methyl cellulose binder, and in contrast to wax crayons which are made without oil. The surface of an oil pastel painting is less powdery than one made from gum pastels, but more difficult to protect with a fixative.

History

At the end of World War I, Kanae Yamamoto proposed an overhaul of the Japanese education system. He thought that it had been geared too much towards uncritical absorption of information by imitation and wanted to promote a less restraining system, a vision he expounded in his book Theory of self-expression which described the Jiyu-ga method, "learning without a teacher". Teachers Rinzo Satake and his brother-in-law Shuku Sasaki read Yamamoto's work and became fanatical supporters. They became keen to implement his ideas by replacing the many hours Japanese children had to spend drawing ideograms with black Indian ink with free drawing hours, filled with as much color as possible. For this, they decided to produce an improved wax crayon and in 1921 founded the Sakura Cray-Pas Company and began production. The new product was not completely satisfactory, as pigment concentration was low and blending was impossible, so in 1924 they decided to develop a high viscosity crayon: the oil pastel. This used a mixture of mashed paraffin wax, stearic acid and coconut oil as a binder. Designed as a relatively cheap, easily applied, colorful medium, oil pastels granted younger artists and students a greater freedom of expression than the expensive chalk-like pastels normally associated with the fine arts. Until the addition of a stabiliser in 1927, oil pastels came in two types: winter pastels with additional oil to prevent hardening and summer pastels with little oil to avoid melting. State schools could not afford the medium and, suspicious of the very idea of "self-expression" in general, favoured the coloured pencil, a cheaper German invention then widely promoted in Europe as a means to instill work discipline in young children.

Oil pastels were an immediate commercial success and other manufacturers were quick to take up the idea, such as Dutch company Talens, who began to produce Panda Pastels in 1930. However, none of these were comparable to the professional quality oil pastels produced today. These early products were intended to introduce western art education to Japanese children, and not as a fine arts medium, although Sakura managed to persuade some avant-garde artists to acquaint themselves with the technique, among them Pablo Picasso. In 1947, Picasso, who for many years had been unable to procure oil pastels because of the war conditions, convinced Henri Sennelier, a French manufacturer who specialized in high quality art products, to develop a fine arts version. In 1949 Sennelier produced the first oil pastels intended for professionals and experienced artists.[1] These were superior in wax viscosity, texture and pigment quality and capable of producing more consistent and attractive work. The Japanese Holbein brand of oil pastels appeared in the mid-1980s with both student and professional grades; the latter with a range of 225 colours.

Use

Oil pastels can be used directly in dry form; when done lightly, the resulting effects are similar to oil paints. Heavy build-ups can create an almost impasto effect. Once applied to a surface, the oil pastel pigment can be manipulated with a brush moistened in white spirit, turpentine, linseed oil, or another type of vegetable oil or solvent. Alternatively, the drawing surface can be oiled before drawing or the pastel itself can be dipped in oil. Some of these solvents pose serious health concerns.[2]

Oil pastels are considered a fast medium because they are easy to paint with and convenient to carry; for this reason they are often used for sketching, but can also be used for sustained works. Because oil pastels never dry out completely, they need to be protected somehow, often by applying a special fixative to the painting or placing the painting in a sleeve and then inside a frame. There are some known durability problems: firstly, as the oil doesn't dry, it keeps permeating the paper. This process degrades both the paper and the colour layer as it reduces the flexibility of the latter. A second problem is that the stearic acid makes the paper brittle. Lastly both the stearic acid and the wax will be prone to efflorescence or "wax bloom", the building-up of fatty acids and wax on the surface into an opaque white layer. This is easily made transparent again by gentle polishing with a woolen cloth; but the three effects together result in a colour layer consisting mainly of brittle stearic acid on top of brittle paper, a combination that will crumble easily. A long term concern is simple evaporation: palmitic acid is often present and half of it will have evaporated within 40 years; within 140 years half of the stearic acid will have disappeared. Impregnation of the entire art work by beeswax has been evaluated as a conservation measure.

Surface and techniques

The surface chosen for oil pastels can have a very dramatic effect on the final painting. Paper is a common surface but this medium can be used on other surfaces including wood, metal, hardboard (often known as "masonite"), MDF, canvas and glass. Many companies make papers specifically for pastels that are suitable for use with oil pastels.

Building up layers of color with the oil pastel, called layering, is a very common technique. Other techniques include underpainting and scraping down or sgraffito. Turpentine, or similar liquids such as mineral spirits, are often used as a blending tool to create a wash effect similar to some watercolor paintings. Commercially available oil sketching papers are preferred for such technique.

Grades

There are a number of types of oil pastels, each of which can be classified as either scholastic, student or professional grade.

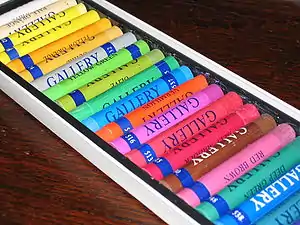

Scholastic grade is the lowest grade; generally the oil pastels are harder and less vibrant than higher grades. It is generally meant for children or new users of oil pastels, and is fairly inexpensive compared to other grades. The middle grade, student grade, is meant for art students and is softer and more vibrant than scholastic grade. They are usually more expensive. Professional grade is the highest grade of oil pastel, and are also the softest and most vibrant, but can be very expensive.

See also

References

- "Art and History Intersect at a Paris Shop". NPR. 2006-07-27. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- "Section 10: Painting and Drawing". Environmental Health & Safety | Baylor University. Retrieved 2018-09-08.

Further reading

- Leslie, Kenneth. Oil Pastel: Materials and Techniques for Today's Artist, Watson-Guptill Publications, 1990. ISBN 0-8230-3310-4.

- M.H.Ellis, "Oil Pastel", in Media and Techniques of Works of Art on Paper, New York University Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York, 1999.

- Elliot, John. Oil Pastel: for the Serious Beginner, Watson-Guptill Publications, 2002. ISBN 0-8230-3311-2.

External links

- The Oil Pastel Society

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070716232500/http://palimpsest.stanford.edu/waac/wn/wn21/wn21-1/wn21-106.html for a discussion of the evaporation and efflorescence.