Nutation (botany)

Nutation refers to the bending movements of stems, roots, leaves and other plant organs caused by differences in growth in different parts of the organ. Circumnutation refers specifically to the circular movements often exhibited by the tips of growing plant stems, caused by repeating cycles of differences in growth around the sides of the elongating stem.[1] Nutational movements are usually distinguished from 'variational' movements caused by temporary differences in the water pressure inside plant cells (turgor).

Simple nutation occurs in flat leaves and flower petals, caused by unequal growth of the two sides of the surface. For example, in young leaf buds the outer surface of each leaflet grows faster, causing it to curve over its neighbors and form a compact bud. As the bud expands, growth becomes more rapid on the inner surface of the leaves, causing the bud to open and the leaves to flatten out. Similar inequality of growth, but more sharply localized, leads to the folding and rolling of the leaf in the bud, and to the changing shapes of flower petals.

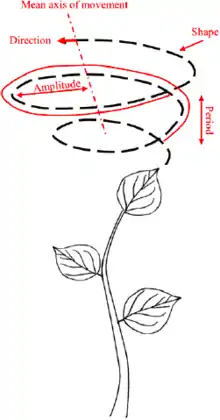

Circumnutational movements are most obvious in growing seedlings, where the combination of circular movement and upward growth causes the tip to move up in a spiral path. The first detailed analysis of circumnutation was Charles Darwin's The Power of Movement in Plants;[2][3] he concluded that most plant movements were modifications of circumnutation, but many counterexamples are now known. Circumnutation is not a direct response to gravity or the direction of illumination, but these factors and many physiological processes can influence its direction, timing and amplitude.[1]

Although the function of circumnutation in most plants is not known, many twining plants have adapted these movements to help them find and twine around vertical objects such as tree trunks, and to help tendrils find and wind around smaller supports.[4] The growing tips of the vine or tendril initially swings in wide circles that maximize its chance of bumping into an obstacle (a potential support). Once the obstacle is encountered the circles tighten, causing the vine or tendril to wind around the support as it grows.

References

- Stolarz, Maria (28 October 2014). "Circumnutation as a visible plant action and reaction". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 4 (5): 380–387. doi:10.4161/psb.4.5.8293. PMC 2676747. PMID 19816110.

Circumnutation is a helical organ movement widespread among plants.

- Darwin, Charles, 1809-1882, author. The power of movement in plants. ISBN 978-0-19-180518-9. OCLC 981425326.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Brown, Allan H. (September 28, 1992). "Circumnutations: From Darwin to Space Flights" (PDF). Plant Physiology. 101 (2): 345–348. doi:10.1104/pp.101.2.345. PMC 160577. PMID 11537497.

- Fiorello, Isabella; Del Dottore, Emanuela; Tramacere, Francesca; Mazzolai, Barbara (2020-03-20). "Taking inspiration from climbing plants: methodologies and benchmarks—a review". Bioinspiration & Biomimetics. 15 (3): 031001. doi:10.1088/1748-3190/ab7416. ISSN 1748-3190. PMID 32045368.

External links

- "Nutation of sunflower seedling". Retrieved 2010-12-29.