Nunney Castle

Nunney Castle is a medieval castle at Nunney in the English county of Somerset. Built in the late 14th century by Sir John Delamare on the profits of his involvement in the Hundred Years War, the moated castle's architectural style, possibly influenced by the design of French castles, has provoked considerable academic debate. Remodelled during the late 16th century, Nunney Castle was damaged during the English Civil War and is now ruined.

| Nunney Castle | |

|---|---|

| Somerset, England | |

In 2018 | |

Shown within Somerset | |

Nunney Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51°12′37″N 2°22′42″W |

| Grid reference | grid reference ST736457 |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Lias Oolite stone |

| Events | English Civil War |

English Heritage maintains the site as a tourist attraction. The architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner has described Nunney as "aesthetically the most impressive castle in Somerset."[1]

History

14th century

Nunney Castle was built near the village of Nunney in Somerset by Sir John Delamare.[2] Delamare had been a soldier during the Hundred Years War with France, where he had made his fortune.[3][nb 1] He obtained a licence to crenellate from Edward III to build a castle on the site of his existing, unfortified manor house in 1373 and set about developing a new, substantial fortification.[2][5]

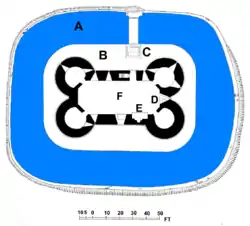

The resulting castle centred on a stone tower-keep, measuring 60 feet by 24 feet (18 m by 7 m) internally and 54 feet (16 m) tall, with four round corner-towers.[2][6][7] The tower-keep had eight-foot (2.4 m) thick walls made from Lias Oolite ashlar stone and was designed around three floors.[8][9] The corner towers had conical roofs and prominent machicolations.[2] The ground floor of the tower-house included the kitchen and other service areas.[8] The functions of the first and second floors are uncertain; one theory is that the first floor was another service area, with the hall on the second floor; another approach argues that the first floor formed the hall, and the second floor living accommodation; a minority view proposes that the first floor was an armoury.[5][6][8][10][nb 2] The third floor was used as living accommodation for the owning family. The original design had a number of windows and fireplaces on the upper floors, but the hall would have been relatively dark and the stairs were inconveniently narrow.[11]

The tower-keep had a modest entrance, which was reached by a draw-bridge that lay across the surrounding moat, which initially reached right up to the base of the castle.[2] A simple, 12-foot (3.6 m) high bailey wall, with minimal defensive value, surrounded the moat, which was in contrast wide, 10-foot (3 m) deep, and would have been difficult for an attacker to drain.[6][7][12][13] On the east side of the castle Nunney Brook was used as a line of defence rather than a bailey wall.[7]

Historians, such as Adrian Pettifer and Stuart Rigold, previously believed that the design of Nunney was heavily influenced by the French castle designs that Delamare would have seen on his military campaigns.[3] Nunney closely resembles the Bastille in Paris, for example, and the machicolations are typical of those found in French castles.[3]

Nunney was considered a conservative, even slightly backward design and probably built to protect against French invasion.[3][12] Historians such as Robert Liddiard and Matthew Johnson are now less certain. Nunney is regarded as a bold, striking design, similar in many ways to those at Herstmonceux or Saltwood Castle.[14] Whilst Nunney does resemble many French castles, there is no direct evidence that it was built in imitation of these designs, and indeed there are other English castles, such as Mulgrave and Dudley, that have a similar structure to Nunney's.[6][15] Nunney Castle may be better understood instead as characteristic of a wider range of tower-keeps built in England during the period, designed, as Nigel Pounds puts it, "to allow very rich men to live in luxury and splendour."[16]

15th - 16th centuries

Nunney Castle was inherited by John's son, Philip Delamere, and grandson, Elias, before passing by marriage into the Poulet family following Elias' probable death during Henry V's campaigns in France.[17] Sir John Poulet and his son John, and grandson, also called John, held the castle during most of the 15th century, but their primary residence was Basing Castle in Hampshire rather than Nunney.[18] William Paulet, the Marquess of Winchester, was the final member of the family to own the castle; after his death in 1572 it passed rapidly through several owners and in 1577 was sold by Swithun Thorpe to John Parker, who only kept it for a year before selling it to Richard Prater, at a cost of £2,000.[19][nb 3]

The castle was redeveloped in the second half of the 16th century, probably by the Praters: the windows were enlarged to let in more light; a grand staircase was built in one of the towers; a Catholic altar was installed, and a revetment, or terrace, was built around the inside of the moat, leaving it 25 feet (7.6 m) wide.[2][23][24]

17th - 19th centuries

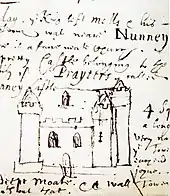

Nunney Castle continued to be owned by the Roman Catholic Prater family into the 17th century.[25] In 1642 the English Civil War broke out between the rival factions of Parliament and the king; like many Catholics, Colonel Richard Prater supported Charles I.[25] As the war progressed the Royalist situation deteriorated, however, and the south-west became one of the few remaining Royalist strongholds; Nunney Castle was garrisoned in anticipation of Parliamentary attack and took in a number of refugees, including many Catholics.[25][26] In September 1645 a Parliamentary army under the command of Lord Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell advanced into Somerset, taking Sherborne, Cary and Shepton Mallet before turning to Nunney.[25] Two regiments of soldiers with cannons surrounded the castle on 18 September; when Richard Prater refused to surrender, the cannons opened fire on the north side of the castle, breaching the castle wall.[25] Richard continued to resist, hoisting a flag with a Catholic crucifix on it above the castle to taunt the besiegers, but two days later the garrison surrendered.[25]

Due to the damage caused by the cannon, the castle escaped the slighting, or deliberate damaging, that occurred to many other castles at the end of the civil war.[25] Nonetheless, Richard Prater was forbidden to return to the castle, despite his promises to support Parliament, and his son, George Prater, only recovered Nunney from its interim owners after Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660.[27]

The castle declined and was sold by the Praters to William Whitchurch around 1700.[28] During the 18th century the building was still in a reasonable condition and in 1789 an order was received to make it ready to receive French prisoners, although it is unlikely that they ever arrived.[29]

20th - 21st centuries

By the 20th century, Nunney Castle was increasingly ruined and covered in thick ivy. As a result, on 25 December 1910 a portion of the damaged north wall entirely collapsed — most of the fallen stone is believed to have been stolen by local residents.[2][28] In 1926, with the fabric of the castle under threat, the owner, Robert Bailey-Neale, transferred the property to the Commissioner of Works, who began a programme of restoration work.[28]

The castle is now run by English Heritage as a tourist attraction and is a scheduled monument.[30] The architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner has described the castle as "aesthetically the most impressive castle in Somerset."[1]

Notes

- Stuart Rigold notes that this description of Delamare's career stems from a single historical source.[4]

- Stuart Rigold proposes that the hall was on the second floor, with servants quarters and service offices on the first; Anthony Emery questions the practicality of this design, placing the hall on the first floor; Andor Gomme and Alison Maguire argue in favour of an armoury forming much of the first floor.[6][8][10]

- It is difficult to accurately compare 16th century and modern prices or incomes. Depending on the measure used, £2,000 in 1577 could equate to either £381,000 (using the retail price index) or £5,220,000 (using the average earnings index). For comparison, a wealthy knight of the period, such as William Darrell, owning 25 manors, enjoyed an annual income of around £2,000.[20][21][22]

References

- Pevsner, p.238.

- Emery, p.604.

- Pettifer, p.223.

- Rigold, p.4.

- Nunney Castle, Somerset Historic Environment Record, Somerset County Council, accessed 1 July 2011.

- Gomme and Maguire, p.15

- Rigold, p.10.

- Emery, pp.604-5

- Ashurst and Dimes, p.99.

- Rigold, p.11.

- Emery, p.605.

- Brown, p.94.

- King, p.157.

- Liddiard, p.58.

- Johnson, pp.32, 110.

- Pounds, p.270.

- Rigold, pp.4-5.

- Rigold, p.5.

- Dunning (2005), p.22.

- Purchasing Power of British Pounds from 1264 to Present, Measuring Worth website, accessed 9 June 2011

- Singman, p.36.

- Hall, p.10.

- Rigold, pp.9-10, 14

- Dunning (2007), p.67

- Rigold, p.6.

- Wedgwood, pp. 496–7.

- Rigold, pp.6-7.

- Rigold, p.7.

- Dunning (1995), pp.63-65.

- Nunney Castle, Gatehouse website, accessed 9 June 2011.

Bibliography

- Ashurst, John and Francis G. Dimes. (2002) Conservation of Building and Decorative Stone. Oxford: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7506-3898-2.

- Brown, R. Allen. (1962) English Castles. London: Batsford. OCLC 1392314.

- Dunning, Robert. (1995) Somerset Castles. Tiverton, UK: Somerset Books. ISBN 978-0-86183-278-1.

- Dunning, Robert. (2005) A Somerset Miscellany. Tiverton, UK: Somerset Books. ISBN 0-86183-427-5.

- Dunning, Robert. (2007) Somerset Churches and Chapels: Building Repair and Restoration. Tiverton, UK: Halsgrove. ISBN 978-1841145921.

- Emery, Anthony. (2006) Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, 1300–1500: Southern England. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58132-5.

- Gomme, Andor and Alison Maguire. (2008) Design and Plan in the Country House: from castle donjons to Palladian boxes. Yale: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12645-7.

- Hall, Hubert. (2003) Society in the Elizabethan Age. Whitefish, US: Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-3974-9.

- Johnson, Matthew. (2002) Behind the castle gate: from Medieval to Renaissance. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-25887-6.

- Liddiard, Robert. (2005) Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2.

- Pettifer, Adrian. (2002) English Castles: a Guide by Counties. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-782-5.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus. (1958) North Somerset and Bristol. London: Penguin Books. OCLC 459446734.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville. (1994) The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: a social and political history. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.

- Rigold, Stuart. (1975) Nunney Castle: Somerset. London: HMSO. ISBN 0-11-670005-X.

- Singman, Jeffrey L. (1995) Daily life in Elizabethan England. Westport, US: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29335-1.

- Wedgwood, C. V. (1970) The King's War: 1641–1647. London: Fontana. OCLC 58038493.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nunney Castle. |

- Nunney Castle, English Heritage

- How Nunney Castle was saved, Visit Nunney