North American jaguar

The North American jaguar is a jaguar (Panthera onca) population in North America, from the southwestern United States to Central America.[1] This population has declined over decades and almost eliminated by 1960.[2]

Results of morphologic and genetic research failed to find evidence for subspecific differentiation.[3][4]

This population is also referred to as the "American jaguar"[5] and "Central American jaguar".[6]

Taxonomic history

Initially, a number of jaguar subspecies were described:[7]

- The taxonomic name Panthera onca goldmani (Mearns, 1901) was proposed as ranging from the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, in the north, to Belize and Honduras in the south.[7]

- Panthera onca hernandesii (Mearns, 1901) was proposed as native to Mexico and the United States of America.[4][7]

- Panthera onca veraecruscis (Nelson and Goldman, 1933) was proposed as ranging from Tabasco in Mexico to Texas in the United States.[7]

- Panthera onca arizonensis (Goldman, 1932) was proposed with a range from Sonora in Mexico, to the southwestern part of United States, before 1939.[7]

- Panthera onca centralis (Mearns, 1901) was proposed for Central America.[7][8]

In 1939, Reginald Innes Pocock did not find evidence for morphological distinction between P. o. hernandesii, P. o. centralis and P. o. arizonensis and considered them one subspecies. Recent tests failed to establish evidence for different subspecies of the jaguar.[3]

Evolution

The modern jaguar is thought to have descended from a pantherine ancestor in Asia that crossed the Beringian land bridge into North America during the Early Pleistocene. From North America, it spread to Central and South America. The ancestral jaguar in North America is referred to as Panthera onca augusta.[4]

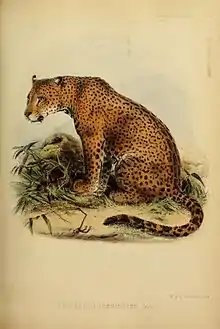

Characteristics

Unlike jaguars in South America, jaguars in Central or North America are fairly small.[9] Those in the Chamela-Cuixmala Biosphere Reserve on the Mexican Pacific coast weigh just about 50 kg (110 lb), similar in weight to female cougars.[10] 57.2 kg (126 lb) was the average for six males in Belize,[11] making them similar to South American females in Venezuela.[7]

Ecology and behavior

In northeastern Mexico, jaguars co-occur with cougars. Both are foremost active at night and prey on white-tailed deer, collared peccary and cattle calves.[12]

Other sympatric predators in the region include the grizzly bear and American black bear. There is evidence that El Jefe preyed on an American black bear.[5]

In July 2018, in the Central American section of the Audubon Zoo in the US city of New Orleans, Louisiana, a 3-year-old male called 'Valerio' escaped from its enclosure, which had a roof in poor condition. It killed four alpacas, an emu and a fox, and injured two other alpacas and a fox, before being captured about an hour after its escape was notified. The killings were apparently the result of a territorial dispute. Its behavior was not deemed to be abnormal for its species.[13][14]

Habitat and distribution

In North America, the jaguar ranges from the southern part of the United States in the north, to the southern part of Central America in the south.[2] As recently as 2016, jaguars of Mexican origin[15] have been spotted in Arizona.[16][17][18]

United States

In 1799, Thomas Jefferson recorded the jaguar as an animal of the Americas.[19] There are multiple zoological reports of jaguars in California, two as far north as Monterey in 1814 (Langsdorff) and 1826 (Beechey).[20]

The coastal Diegueño (Kumeyaay people) of San Diego and Cahuilla Indians of Palm Springs had words for jaguar and the cats persisted there until about 1860.[21] The only recorded description of an active jaguar den with breeding adults and kittens in the United States was in the Tehachapi Mountains of California, prior to 1860.[20] In 1843, Rufus Sage, an explorer and experienced observer recorded jaguar present on the headwaters of the North Platte River 30–50 mi (48–80 km) north of Longs Peak in Colorado. Cabot's 1544 map has a drawing of jaguar ranging over the Pennsylvania and Ohio valleys. Historically, the jaguar was recorded in far eastern Texas, and the northern parts of Arizona and New Mexico. However, since the 1940s, the jaguar has been limited to the southern parts of these states. Although less reliable than zoological records, Native American artefacts with possible jaguar motifs range from the Pacific Northwest to Pennsylvania and Florida.[22]

By the late 1960s, jaguars were thought to have been eliminated in the United States. A female was shot by a hunter in Arizona's White Mountains in 1963. Arizona outlawed jaguar hunting in 1969, but by then no females remained and over the next 25 years only two male jaguars were found (and killed) in Arizona. Then in 1996, Warner Glenn, a rancher and hunting guide from Douglas, Arizona, came across a jaguar in the Peloncillo Mountains and became a researcher on jaguars, placing webcams which recorded four more Arizona jaguars.[23] No jaguars sighted in Arizona in the last 15 years had been seen since 2006.[24] Then, in 2009, a male jaguar named Macho B died shortly after being radio-collared by Arizona Game and Fish Department (AGFD) officials in 2009. In the Macho B incident, a former AGFD subcontractor pleaded guilty to violating the endangered species act for trapping the cat and a Game and Fish employee was fired for lying to federal investigators. In 2011, a male jaguar weighing 200 lb (91 kg) was photographed near Cochise in southern Arizona by a hunter after being treed by his dogs (the animal left the scene unharmed). A second 2011 sighting of an Arizona jaguar was reported by a Homeland Security border pilot in June 2011, and conservation researchers sighted two jaguars within 30 mi (48 km) of the border between Mexico and the United States in 2010.[25]

In September 2012, a jaguar was photographed in the Santa Rita Mountains of Arizona, the second such sighting in this region in two years.[26] This jaguar has been photographed numerous times over the past nine months through June 2013.[27] On 3 February 2016, the Center for Biological Diversity released a video of this jaguar – now named El Jefe (Spanish for "The Boss") – roaming the Santa Rita Mountains, about 25 mi (40 km) south of downtown Tucson.[28] El Jefe is the fourth jaguar sighted in the Madrean Sky Islands in southern Arizona and New Mexico, over the last 20 years.[5]

On 16 November 2016, a jaguar was spotted in the Dos Cabezas Mountains of Arizona, 60 mi (97 km) from the Mexican border, the farthest north one of these animals has been spotted in many decades. It is the seventh jaguar to be confirmed in the Southwest since 1996.[18] On 1 December 2016, another male jaguar was photographed on Fort Huachuca also in Arizona.[17] In February 2017, authorities revealed that a third jaguar had been photographed in November 2016, by the Bureau of Land Management in the Dos Cabezas Mountains, also in Arizona, some 100.0 km (62.1 miles) north of the border with Mexico.[18] The only picture obtained allowed experts to determine this is a different individual, but it does not reveal its gender.

Conservation

Legal action by the Center for Biological Diversity led to federal listing of the cat on the endangered species list in 1997. However, on January 7, 2008, George W. Bush appointee H. Dale Hall, Director of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), signed a recommendation to abandon jaguar recovery as a federal goal under the Endangered Species Act. Critics, including the Center of Biological Diversity and New Mexico Department of Game and Fish, were concerned the jaguar was being sacrificed for the government's new border fence, which is to be built along many of the cat's typical crossings between the United States and Mexico.[29]

In 2010, however, the Obama Administration reversed the policy of the Bush Administration, and pledged to protect "critical habitat" and draft a recovery plan for the species. The USFWS was ultimately ordered by the court to develop a jaguar recovery plan and designate critical habitat for the cats.[25] On 20 August 2012, the USFWS proposed setting aside 838,232 acres in Arizona and New Mexico — an area larger than Rhode Island — as critical jaguar habitat.[30] On 4 March 2014 Federal wildlife officials set aside nearly 1,200 square miles along the U.S.-Mexico border as habitat essential for the conservation of the jaguar. The reservation includes parts of Pima, Santa Cruz and Cochise counties in Arizona and Hidalgo County in New Mexico.[31] In September 2015, El Jefe was photographed via camera trap and analysis of his spots confirms that he has been in southeastern Arizona (30 mi (48 km) south of Tucson) since 2011. Jaguars have been present in this region every year since 1997.[32] El Jefe and other males may have originated from a breeding population in Sonora, Mexico, 125 mi (201 km) to the south of Tucson.[33]

Northern Jaguar Project

The Northern Jaguar Project is a conservation effort on behalf of the jaguar that is headed by an Arizona-based organization of the same name, in conjunction with Mexico's Naturalia. It is focused on protecting the jaguars living near the border between the United States and Mexico. The core of the project is the Northern Jaguar Reserve. The project began in 2003 with the purchase of the 10,000 acre Los Pavos Ranch in northern Mexico, just 125 mi (201 km) south of the border. In 2008 it was expanded to more than double its size when Rancho Zetasora was acquired. Both ranches are remote, difficult to access, and relatively untouched, making them perfect habitat, not just for jaguars, but for many other species as well. The Northern Jaguar Project is the "northernmost location where jaguars, mountain lions, bobcats, and ocelots are all found in the same vicinity", and the park also features a variety of floral habitats as well.[34][35]

The project is also focused on efforts to create a stable jaguar population in Northwestern Mexico. However, its long term aspirations include a return of the jaguar to the Southwestern United States. The potential for such a re-introduction is deemed high, since as much as 30% of Arizona alone is considered to be a suitable habitat for the jaguar.[15]

Threats

San Bernardino National Wildlife Refuge is close to the proposed border barrier, and since the proposed project would cut through a migration corridor for the jaguar between Mexico and the USA, it may interfere with the migration of Mexican jaguars to the USA, not withstanding other animals.[36][37]

Gallery

_negra.jpg.webp)

_(6766731069).jpg.webp) A melanistic jaguar at Belize Zoo

A melanistic jaguar at Belize Zoo A captive jaguar in Vara Blanca, Heredia, Costa Rica

A captive jaguar in Vara Blanca, Heredia, Costa Rica

Cultural significance

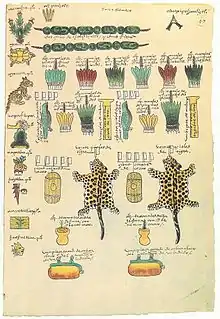

- The jaguar is prominent in Mesoamerican culture. For instance, in the days of the Maya civilization, a king would sit upon a cushion made of jaguar skin, during coronation,[38] and a number of their deities were based on it.[39] The werejaguar was a motif and supernatural entity for Olmecs.[40] The Aztecs had an elite group of warriors known as ocēlōmeh (plural for ocēlōtl, that is "jaguar warrior").[41]

- In contemporary culture, the jaguar features as sports team mascot, such as the names of the South Alabama Jaguars[42] and Jacksonville Jaguars.[43] A red jaguar was adopted as the first official mascot for the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City.[44]

See also

References

- Guerrero, D.L. (24 February 2009). "North American Jaguar (Panthera onca) Collared in Arizona". Arkanimals.com. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Nowell, K.; Jackson, P., eds. (1996). "Panthera Onca" (PDF). Wild Cats. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN/SSC Cat Specialist Group. IUCN. pp. 118–122. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- Larson, S. E. (1997). "Taxonomic re-evaluation of the jaguar". Zoo Biology. 16 (2): 107–120. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-2361(1997)16:2<107::AID-ZOO2>3.0.CO;2-E.

- Ruiz-Garcia, M.; Payan, E.; Murillo, A. & Alvarez, D. (2006). "DNA microsatellite characterization of the jaguar (Panthera onca) in Colombia". Genes & Genetic Systems. 81 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1266/ggs.81.115. PMID 16755135. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- Grant, R. (2016). "The Return of the Great American Jaguar". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "Panthera onca centralis Central American Jaguar". Encyclopedia of Life. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Seymour, K. L. (1989). "Panthera onca" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 340 (340): 1–9. doi:10.2307/3504096. JSTOR 3504096. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 27 December 2009.

- Baker, Taxonomy, pp. 5–7.

- Francis, Adama M.; Iserson, K. V. (2015). "Jaguar Attack on a Child: Case Report and Literature Review". Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 16 (2): 303–309. doi:10.5811/westjem.2015.1.24043. PMC 4380383. PMID 25834674.

- Nuanaez, R.; Miller, B.; Lindzey, F. (2000). "Food habits of jaguars and pumas in Jalisco, Mexico". Journal of Zoology. 252 (3): 373–379. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb00632.x. Retrieved 8 August 2006.

- Rabinowitz, A. R. (1986), Jaguar predation on domestic livestock in Belize, 14, Wildlife Society Bulletin, pp. 170–174

- Gutiérrez-González, C. E.; López-González, C. A. (2017). "Jaguar interactions with pumas and prey at the northern edge of jaguars' range". PeerJ. 5 (5): e2886. doi:10.7717/peerj.2886. PMC 5248577. PMID 28133569.

- Silverstein, Jason (14 July 2018). "Jaguar escapes, kills 6 animals at New Orleans zoo". CBS News. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- Krueger, Hanna (14 July 2018). "6 animals dead, 3 injured: What we know about the jaguar escape at Audubon Zoo". NOLA.com. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- Hatten, J.R. (2005). "A spatial model of potential jaguar habitat in Arizona". Journal of Wildlife Management. 69 (3): 1024–1033. doi:10.2193/0022-541x(2005)069[1024:asmopj]2.0.co;2.

- Arizona Game and Fish Department (2011). "Game and Fish confirms report of jaguar in southern Arizona". Arizona Game and Fish Department Media web page. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- Ames, J. (2016). "Jaguar seen on Fort Huachuca trail camera". Jaguar seen on Fort Huachuca. Raycom Media. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- "Rare jaguar sighting in Arizona, 60 miles north of Mexican border". Newsweek. 2017. Retrieved 3 March 2017.

- "Full text of "The writings of Thomas Jefferson"".

- Merriam, C. Hart (1919). "Is the Jaguar Entitled to a Place in the California Fauna?". Journal of Mammalogy. 1: 38–40. doi:10.1093/jmammal/1.1.38.

- Pavlik, Steve (2003). "Rohonas and Spotted Lions: The Historical and Cultural Occurrence of the Jaguar, Panthera onca, among the Native Tribes of the American Southwest". Wicazo Sa Review. 18 (1): 157–175. doi:10.1353/wic.2003.0006. JSTOR 1409436. S2CID 161236104.

- Daggett, Pierre M.; Henning, Dale R. (1974). "The Jaguar in North America". American Antiquity. 39 (3): 465–469. doi:10.2307/279437. JSTOR 279437.

- Will Rizzo (December 2005). "Return of the Jaguar?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Davis, Tony; Steller, Tim (22 November 2011). "Jaguar seen in area of Cochise". Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 23 November 2011.

- Christie, Bob (1 December 2011). "Excitement follows 2 jaguar sighting in Arizona". The Arizona Republic. Archived from the original on 7 March 2015.

- Davis, Tony (25 November 2012). "Jaguar photo taken near Rosemont". azstarnet.com. Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- Tony Davis (28 June 2013). "Jaguar roves near Rosemount mine site". Arizona Daily Star. Archived from the original on 29 June 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- "Video shows only known US jaguar roaming Arizona mountains". The Boston Globe. 3 February 2016.

- Matlock, Staci (17 January 2008). "Jaguar recovery efforts lack support from federal agency" (PDF). The New Mexican. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- Greenberg, Susan H. (21 August 2012). "Kitty Corner: Jaguars Win Critical Habitat in U.S." Scientific American. Archived from the original on 7 October 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

- Montoya Bryan, Suasan (4 March 2014). "Feds set aside habitat in Southwest for jaguar". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 7 March 2015.

- Jessica Lamberton-Moreno (8 September 2015). "Student project results in new jaguar sighting". Sky Island Alliance. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- Handwerk, Brian (3 February 2016). "Only Known Jaguar in U.S. Filmed in Rare Video". National Geographic News. Retrieved 4 February 2016.

- "The Northern Jaguar Project". Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- "Species of Concern". Northern Jaguar Project. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- Lakhani, Nina (29 December 2019). "Water-guzzling demands of Trump's border wall threaten fish species". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- "Trump Bulldozes New Wall Through Wildlife Refuge, Jaguar Country". Center for Biological Diversity. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Martin and Grube 2000, p. 14.

- Demarest 2004, p. 181.

- Coe (1968), p. 42. Diehl, p. 104.

- Nahuatl Dictionary. (1997). Wired Humanities Project. University of Oregon. Retrieved September 5, 2012, from link

- "The Official Website of the South Alabama Jaguars". South Alabama Jaguars. Retrieved 20 January 2018.

- Sexton, Brian (4 November 2014). "Jaguars History". Jacksonville Jaguars. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Welch, P. (1988). Cute Little Creatures: Mascots Lend a Smile to the Games (PDF). la84foundation.org. Retrieved 11 November 2011.