Nimona

Nimona is a fantasy webcomic by the American comics writer and artist Noelle Stevenson. Stevenson started Nimona while a student at Maryland Institute College of Art.[1] The webcomic began publication in June 2012[2] and doubled as Stevenson's senior thesis.[3] Nimona was published as a graphic novel by HarperCollins in 2015. The comic has won an Eisner Award,[4] a Cybils Award,[5] and a Cartoonist Studio Prize.[6] It was adapted into an audiobook in 2016. An animated feature film adaptation, produced by Blue Sky Studios, was announced in 2015[7] and is scheduled to be released in January 14, 2022.[8]

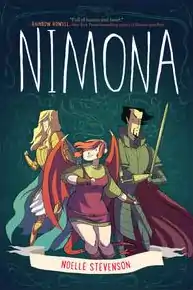

| Nimona | |

|---|---|

Cover of the print edition | |

| Author(s) | Noelle Stevenson |

| Current status/schedule | Concluded |

| Publisher(s) | Print: HarperCollins |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure Science fantasy Comedy-drama Thriller |

Synopsis

Nimona is set in a world that combines medieval and futuristic settings, mixing magic and mad science. Ballister Blackheart is a former knight turned low-grade villain whose evil plots are routinely foiled by his nemesis, Sir Ambrosius Goldenloin of the Institution of Law Enforcement and Heroics. The two men once were friends – or perhaps more – but they fell out and Ballister lost an arm in a fight with Goldenloin and now has a mechanical arm.[2][9] Ballister has been ejected from the Institution because of his missing arm and became a villain.[10]

The titular character Nimona is a teenage shapeshifter who breaks into Ballister’s lair and anoints herself as his sidekick. Ballister is a mastermind but is reluctant to kill and carefully follows his own moral code,[3] which frustrates Nimona who is also smart but is conniving and needlessly violent.[9] While the initial chapters follow Nimona and Ballister's adventures and growing friendship, eventually Nimona’s desire for bloodlust puts her and Ballister into conflict with Goldenloin. The Institute wants Nimona killed and instructs Goldenloin to do it, while Ballister wants to protect Nimona and bring down the corrupt organization, and Nimona has her own vengeful plans.[2]

When asked to describe her work "in as boring a way as possible", Noelle Stevenson described Nimona as: "man's new assistant doesn't care for his ex-boyfriend."[11]

Conception and development

In a course as Maryland Institute College of Art, Stevenson received an assignment to create a new character, and revisited an idea from high school of a female shapeshifter. According to Stevenson, she combined this character with a Joan of Arc-inspired character that she was drawing at the time to create Nimona.[1] She was inspired to create Nimona's look based on her experiences with cosplay: Stevenson preferred cosplaying as male characters rather than female characters, and wanted "to do a costume that people who weren't interested in looking particularly buxom or sensual might want to dress as."[12][13] Other characters and a story followed as Stevenson revisited the concept several times over her junior year, and later received approval for the comic to be her senior thesis.[1]

Publication

Stevenson initially published Nimona online on Tumblr.[1][12][14] The comic began as a collection of one- and two-page comics. Stevenson says that she "had no idea what Nimona was when I started it" and that it was experimental, but that she knew very early how it would end.[15] Shortly after posting the first few pages, an agent reached out to her, and while Stevenson was still at school she learned her agent had sold Nimona to the publisher HarperCollins.[1]

The webcomic ran from June 2012 to September 2014.[2] Stevenson said that completing Nimona was both satisfying and "a little sad."[15] HarperCollins published the completed comic as a young adult graphic novel in May 2015.[1][16][17]

Reception

Awards

Nimona has been well received. It has won an Eisner Award,[4] a Cybils Award,[5] and a Cartoonist Studio Prize.[6] It has also been nominated for another Eisner Award and a National Book Award.[18][19] The hardcover collection of Nimona became a New York Times bestseller.[20]

| Year | Category | Institution or publication | Result | Notes | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Best Graphic Album—Reprint | Eisner Awards | Won | Reprint by Harper Teen | [4] |

| 2015 | Young Adult Graphic Novels | Cybils Award | Won | [5] | |

| 2015 | Best Digital/Web Comic | Eisner Awards | Nominated | [18][4] | |

| 2015 | Young People's Literature | National Book Awards | Nominated | Stevenson, at 23, was possibly the youngest NBA nominee in any category this year. | [21][1][19] |

| 2012 | Best Web Comic | Cartoonist Studio Prize | Won | [6] |

Reviews

A reviewer for io9 called Nimona one of the "Best New and Short Webcomics of 2012", commenting that its "light, sketchy style" helped to set up the comic's tone, and compared it favorably to The Venture Bros.[9][22] Nimona was rated as the best webcomic of 2014 by Paste Magazine.[23] In a 2020 article for CNN's Underscored, Daniel Toy described Nimona as a "modern fantasy epic" that will "delight teen readers."[24] A columnist for The Mary Sue said that Nimona and comics like it "promote alternate perspectives on gender".[25] Reviewing the German-language print version of Nimona in 2016, a writer for Spiegel Online described the webcomic as "entertaining" through its "wonderfully" staged and colored action scenes.[26]

A writer for Comic Book Resources compared Stevenson's artwork to that of Kate Beaton, Eleanor Davis and Faith Erin Hicks.[3] A reviewer for Tor.com said of the art, "Stevenson’s artistic style is VERY unique and VERY quirky, and I mean that with the highest praise... The first two chapters of Nimona are pretty clunky, but in a twee rather than off-putting way. By the third chapter she starts to take some real chances with her art, and by chapter five it’s an absolute joy to look at."[2] Additionally, Emma Patton in the Children's Book and Media Review journal described Nimona as intentionally featuring the "cliches of good vs. evil stories" in order to expose the triteness of the clitches themselves, and noted that one of the most important themes is identity.[27]

Academic analysis

Associate Professor Mihaela Precup considered that mainstream publications which reviewed the comic did not note "any of the queer references," which she described as an "important part in the book’s positioning of monstrosity," and highlighted what she called a "subversive potential of a specific kind of queer cuteness." Precup also stated that the queerness of Nimona is "mostly hinted at through linguistic markers" and noted in her fashion choices as well, while describing Nimona as a "cute monster girl" and saying that the book shows that violence is located in "institutions that control and persecute."[28]

Molly Clare Barnewitz produced her Master of Arts thesis on animal and other non-normative bodies in queer comics, focusing on Nimona and On Loving Women. Barnewitz said that "Nimona depicts the threat posed by fluid and non-normative identities to heteronormative hegemonic institutions, ultimately demanding that the binary systems that persecute queerness be abolished." Barnewitz said that the comic "attack[s] exclusionary systems that place queerness as the ultimate other". She described Nimona as an example of the possibility of "reading comics through a queer lens," while noting that the story "evokes traditions of fairy tale and cyborg science fiction," focuses on shifting identity of Nimona and Ballister as they fight the over-controlling Institute, and says it breaks down "socially constructed binaries."[10]

Associate Professor James J. Donahue, in a paper in The Oxford Handbook of Comic Book Studies, said that "Stevenson has used her graphic novels to demonstrate the fluidity of identity construction for a young-adult audience", that it "present[s] empowering moments... [that] are always grounded in the celebration of community." He adds: "...these genres often encourage reading practices based on the acceptance of social norms. In response, Stevenson’s work engages in a form of disruption aimed at challenging normative reading practices, be they literary or social, opening up safe spaces for her readers’ own efforts at coming to terms with their identities."[29]

Heather Wright wrote a Master of Arts thesis on a broader topic, examining the "transformative power of queer world building and intervention" by using children's cartoons like The Legend of Korra, Steven Universe, and Nimona, how this functions, and can be adapted. She argued that the actions by Ballister and Nimona against the Institution "foreground the potential, and process, for undermining institutions." She also states that Stevenson suggests that a way to "take back power" is to disrupt institutions and the conditioning they engender through "fluidity." This is reflected, Wright argues, in Nimona's "original" form being "fluid, unsettled and indefinable," and hence, a construction, like gender, with Wright relating this to Judith Butler's theories about gender. She concludes that Nimona stated that "the blurring of boundaries," especially when it comes to institutions, bodies, and motivations, allows for "hegemonic ideologies and institutions" to be undermined.[30]

Adaptations

In August 2016, Stevenson published an audiobook version of Nimona through Audible. The audiobook features voicework by Rebecca Soler, Jonathan Davis, Marc Thompson, January LaVoy, Natalie Gold, Peter Bradbury, and David Pittu, has a runtime of two hours and seventeen minutes, and is unabridged.[20]

In June 2015, 20th Century Animation acquired the rights for an animated feature film adaptation, with Patrick Osborne set to direct it and Marc Haimes set to write the script.[7] The film will be produced by Blue Sky Studios.[31] In June 2017, Fox scheduled Nimona to be released on February 14, 2020.[14][32] In May 2019, after Disney's acquisition of Fox, the film was delayed to March 5, 2021.[33] In November 2019, the film was delayed again to January 14, 2022.[8]

See also

- Portrayal of women in American comics

- Lumberjanes, another comic by Stevenson

References

- Cavna, Michael (October 16, 2015). "From idea born at MICA, Noelle Stevenson is the youngest 2015 National Book Award finalist". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- Brown, Alex (January 28, 2015). "Pull List: Nimona". Tor.com. Archived from the original on April 26, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Thompson, Kelly (November 5, 2012). "She Has No Head! – "I'm a shark"". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- "2010-Present". Comic-Con International: San Diego. December 2, 2012. Archived from the original on July 23, 2020. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- Alverson, Brigid (February 15, 2016). "'Roller Girl,' 'Nimona' win Cybils awards". Comic Book Resources.

- "Announcing the Winners of the Cartoonist Studio Prize". Slate. March 1, 2013. Retrieved March 4, 2013.

- Kit, Borys (June 11, 2015). "Fox Animation Nabs 'Nimona' Adaptation With 'Feast' Director (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- Kroll, Justin (November 16, 2019). "Ridley Scott's 'The Last Duel' Gets the Greenlight as Disney Dates Multiple Titles". Variety. Retrieved November 16, 2019.

- Davis, Lauren (November 10, 2012). "Saturday Webcomic: What happens when a supervillain's sidekick is more villainous than he is?". io9. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- Barnewitz, Molly Clare (September 12, 2020). The Animal as Queer Act in Comics: Queer Iterations in On Loving Women and Nimona (PDF) (Masters). University of Utah. pp. iii, 50–71. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- Stevenson, Noelle [@Gingerhazing] (July 5, 2020). "Man's new assistant doesn't care for his ex-boyfriend" (Tweet). Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020 – via Twitter. She was responding to a post titled "Describe your own novel in as boring a way as possible."

- "'Nimona' Shifts Shape And Takes Names — In Sensible Armor, Of Course". NPR. May 13, 2015. Archived from the original on September 14, 2020.

- Mumm, Tiffany (August 2017). Girls in Graphic Novels: A Content Analysis of Selected Texts from YALSA's 2016 Great Graphic Novels for Teens List (Masters Thesis). Eastern Illinois University. pp. 37–38. Archived from the original on March 22, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Freedman, Molly (June 30, 2017). "Nimona Animated Movie Gets a 2020 Release Date". ScreenRant. Archived from the original on February 13, 2019. Retrieved September 28, 2020.

- Kahn, Juliet (November 17, 2014). "We're Defining This New Wave Of Comics For Ourselves: A Conversation With Noelle Stevenson [Interview]". Comics Alliance. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015.

- "Art Blogger Noelle Stevenson Lands 2-Book Deal". CBC Books. November 9, 2012. Archived from the original on March 5, 2013.

- MacDonald, Heidi (November 7, 2012). "HarperCollins picks up webcomic Nimona". Comics Beat.

- "2015 Eisner Award Nominations". Comic-Con. 2015. Archived from the original on June 13, 2015.

- Dwyer, Colin (October 14, 2015). "Finalists Unveiled For This Year's National Book Awards". NPR. Retrieved October 14, 2015.

- Sims, Chris (August 26, 2016). "Noelle Stevenson Announces Full-Cast 'Nimona' Audiobook". ComicsAlliance.

- "National Book Awards 2015". National Book Foundation. Retrieved September 29, 2020.

- "The Best New and Short Webcomics of 2012". Io9. Retrieved February 20, 2013.

- Jackson, Fannie (December 17, 2014). "The 20 Best Webcomics of 2014". Paste Magazine.

- Toy, Daniel (September 11, 2020). "The best graphic novels for readers of all ages, from kids to adults". CNN. Archived from the original on September 11, 2020. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- Stoltzfus-Brown, Laura (May 26, 2015). "The Political Economy of the Mysteriously Missing Black Widow". The Mary Sue. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020.

- Vermes, Timur (November 23, 2016). ""Das war lustig! Was machen wir jetzt?"". Spiegel Online. [s Archived] Check

|archive-url=value (help) from the original on s. Check date values in:|archive-date=(help) - Patton, Emma (December 2018). "Nimona". Children's Book and Media Review. 39 (8): 1. Archived from the original on October 14, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Precup, Mihaela (August 23, 2017). "To 'all the monster girls': violence and non-normativity in Noelle Stevenson's Nimona". Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics. 8 (6): 550–559. doi:10.1080/21504857.2017.1361457. Retrieved September 12, 2020.

- Donahue, James J. (September 4, 2020), Aldama, Frederick Luis (ed.), "I'm Not a Kid. I'm a Shark!: Identity Fluidity in Noelle Stevenson'sYoung-Adult Graphic Novels", The Oxford Handbook of Comic Book Studies, Oxford University Press, pp. 454–470, doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190917944.013.7, ISBN 978-0-19-091794-4, retrieved September 30, 2020

- Wright, Heather (May 2018). ""Let's Make Some Trouble for the Institution": The Pedagogy of Queer Activism in Nimona". “The Childish, the Transformative, and the Queer”:Queer Interventions as Praxis in Children’s Cartoons (Masters). City University of New York. pp. 24, 26–29. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Riley, Jennel (February 9, 2017). "Oscar Winner Patrick Osborne Returns With First-Ever VR Nominee 'Pearl'". Variety. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

I’m working with Blue Sky Animation and Fox on “Nimona,...

- Couch, Aaron (June 30, 2017). "Fox Carves Out Dates for 6 Mystery Marvel Movies". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 30, 2017.

- Lang, Brent; Rubin, Rebecca (May 7, 2019). "Disney Announces New 'Star Wars' Films, Moves 'Avatar' Sequels". Variety. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

External links

- Official website, archived on the Wayback Machine