Nguni people

Nguni people are a group of closely related Bantu ethnic groups that reside in Southern Africa. They predominantly live in South Africa. Swazi people live in both South Africa and Eswatini, while Ndebele people live in both South Africa and Zimbabwe.

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Nguni languages | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Sotho-Tswana peoples, Tswa-Ronga peoples, Venda people |

In South Africa, the historic Nguni kingdoms of the Zulu, Xhosa, Ndebele and Swazi are in the present-day provinces of KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape, Gauteng, Limpopo and Mpumalanga. The most notable of these kingdoms is the Zulu Kingdom, which was ruled by Shaka, a powerful warrior king whose conquest took place in the early nineteenth century. In Zimbabwe the Ndebele people live primarily in the provinces of Matabeleland and Midlands.[1]

History

_(14779032674).jpg.webp)

Most of what is believed about ancient Nguni history comes from oral history and legends. Traditionally, they are said to have migrated to Africa's Great Lakes region from the North.[2] According to linguistic evidence—alone—and historians (including John H. Robertson, Rebecca Bradley, T Russel, Fabio Silva and James Steele) the ancestors of the Nguni people migrated from west of the geographic Centre of Africa[3] towards modern-day South Africa 7000 years ago (5000 BC).[4][5][6][7] Nguni people had migrated within South Africa to KwaZulu-Natal by the 1st century AD, and were also present in the Transvaal region at the same time.[8][9][10][11] Nguni people brought with them sheep, cattle, goats and horticultural crops, many of which had never been used in South Africa at that time.[12][9]

Other provinces in present-day South Africa, such as Eastern Cape, saw the emergence of Nguni speakers at around the same time.[13] Some groups split off and settled along the way, while others kept going. Thus, the following settlement pattern formed: the southern Ndebele in the north, the Swazi in the northeast, Zulu towards the east and the Xhosa in the south. Owing to the fact that these people had a common origin, their languages and cultures show marked similarities. The Nguni eventually met with San hunters, which accounts for their use of "click" in their languages.[14]

Although the Northern Ndebele are said to have come from the Nguni people, this is true only for some of them. The South African Ndebeles (Southern Ndebele people) were the first group to separate from other Nguni clans, after entering present-day South Africa and settling in the Transvaal region from around the year 1500. The remaining Nguni clans moved further south. Those that moved south-west ended up calling themselves Xhosas, and most of the clans that moved south-east ended up being forcibly united under the Zulus when Shaka (whose Zulus had been a minor clan under the Mthethwa confederacy led by Dingiswayo, Shaka's overlord) defeated the Ndwandwe confederacy under Zwide kaLanga. Before their defeat by Shaka Zulu they lived in the area north of the Umhlathuze River and south of the Pongola. After their defeat, they moved to the headwaters of the Nkomati river, among other areas (with one of Zwide's generals, Zwangendaba kaJele going as far as Malawi/Tanzania). Mzilikazi, chief of the Khumalo clan, became one of Shaka's top generals after the unification of the clans. Returning from a raid with his impi, he kept some of the stolen cattle for himself rather than handing them over to his overlord, Shaka, as was the custom. Such conduct was punishable by death. A regiment was sent to punish this general, which resulted in him fleeing with hundreds of his followers, eventually ending up in the Transvaal region where they came into contact with the (unrelated) Manala Ndebeles.[15] The Manala Ndebeles had been weakened by their separation from the Nzunza Ndebele after almost two to three centuries of their settlement in the Transvaal region. The separation led to the majority of the nation going with Nzunza and the minority with Manala. The Nzunza Ndebele moved north, and the Manala Ndebele, who were predominantly composed of women, remained in present-day Pretoria. When Mzilikazi arrived, he killed the Manala Ndebele king, King Silamba, and they settled there for a while before moving further north, ending up in present-day Zimbabwe around 1839. By the time they arrived in present-day Zimbabwe, Mzilikazi's Khumalo clan (which had been joined by other ethnic groups, such as the Sotho, Tswana and other displaced Ngunis in South Africa) was known as the Ndebele. Further conquests and assimilation of Zimbabwean groups (such as the Kalanga and Rozwi) meant that the original Khumalos from Zululand was eventually a minority in this large ethnic group, which was united by a common Nguni language, isiNdebele.

Many tribes and clans are said to have been forcibly united under Shaka Zulu. Shaka Zulu's political organisation was efficient in integrating "conquered" tribes, partly by the age regiments, where men from different villages bonded with each other.

Many versions in the historiography of Southern Africa state that during the southern African migrations known as Mfecane, the Nguni peoples spread across a large part of southern Africa, absorbing, conquering or displacing many other peoples. However, the notion of the mfecane/difaqane has been disputed by some scholars, notably, Julian Cobbing.[16] The Mfecane was initiated by Zwide and his Ndwandwe's. They attacked the Hlubi and stole their cattle leaving them destitute. The remnants of the Hlubi under their chief Matiwane fled into what is now the Free State and attacked the Batlokwa in The Harrismith Vrede area. This displaced the Batlokwa under Mantatese and she and her people spread death and destruction further into the central interior. Moshoeshoe and his Bakwena sought the protection of Shaka and sent him tribute in return. When Matiwane settled at Mabolela, near present-day Clocolan, Moshoeshoe complained to Shaka that this prevented him from sending his tribute whereupon an impi was sent to drive Matiwane from this area. Matiwane fled south and was eventually defeated in a battle with British troops in what later became the Transkei. Mantatese and her Batlokwa settled near what is now Ficksburg and was followed by her son, Sekonyela, as chief of the Batlokwa. It was he who had stolen Zulu cattle that Piet Retief in his dealings with Dingane, Shaka's successor, had to retrieve. After the defeat of Zwide and his Ndwandwes by Shaka, two of his commanders, Soshangane and Zwengendaba, fled with their followers northwards creating havoc as they went. Soshangane eventually founded the Shangane nation in Mozambique and Zwengendaba moved all the way to what is now Tanzania. Mzilikazi in his flight from Shaka depopulated the eastern highveld and northern Free State, killing the men and capturing the women to form his Matabele nation. Initially, he settled near what is now Pretoria, then moved to Mosega, near present day Zeerust, but after his defeat by the Voortrekkers he moved to present-day Zimbabwe where he founded his capital Bulawayo.[17]

Social organisation

Within the Nguni nations, the clan, based on male ancestry, formed the highest social unit. Each clan was led by a chieftain. Influential men tried to achieve independence by creating their own clan. The power of a chieftain often depended on how well he could hold his clan together. From about 1800, the rise of the Zulu clan of the Nguni, and the consequent Mfecane that accompanied the expansion of the Zulus under Shaka, helped to drive a process of an alliance between and consolidation among many of the smaller clans.

For example, the kingdom of Eswatini was formed in the early nineteenth century by different Nguni groups allying with the Dlamini clan against the threat of external attack. Today, the kingdom encompasses many different clans who speak a Nguni language called Swati and are loyal to the king of Eswatini, who is also the head of the Dlamini clan.

"Dlamini" is a very common clan name among all documented Nguni languages (including Swati and Phuthi), associated with AbaMbo cultural identity.

Religion

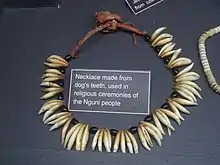

Ngunis may be Christians (whether Catholics or Protestants), practitioners of African traditional religions or members of forms of Christianity modified with traditional African values (such as the Shembe Church of Nazarites).They also follow a mix of these two religions most of the time not separately.

Constituent peoples

The following peoples are Nguni:

| People | Language | Population | Distribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swazi | Swazi | 2,258,000 | Eswatini, but also in South Africa around the Swazi border. Their homeland was KaNgwane. |

| Phuthi | Phuthi | 49,000 | Near the Lesotho-South Africa border in the Transkei region. |

| Lala | Lala | Kranskop, Harding, KwaZulu-Natal, INanda, UMngeni Reserve, | |

| Bhaca | Bhaca | Northeastern part of the Eastern Cape | |

| Northern (Transvaal) Ndebele | Sumayela Ndebele | Primarily in Mokopane, but also in Hammanskraal and around Polokwane | |

| Hlubi | Hlubi | Near the Lesotho-South Africa border in the Transkei region.KwaZulu-Natal, Eastern Cape , Lesotho and North West provinces, with an original settlement on the Buffalo River | |

| Zulu | Zulu | 10,964,000 | Originally Zululand, but now in most of Natal and as a minority in Eastern Transvaal and Gauteng. Their homeland was KwaZulu. |

| Xhosa | Xhosa | 8,478,000 | Their homelands were the Ciskei and the Transkei. |

| Thembu[n 1] | Xhosa | 750,000 | Thembuland. Their homeland was in the Transkei (they are often considered a Xhosa sub-group) |

| Mpondo[n 1] | Xhosa | 2,000,000 | Pondoland. Their homeland was in the Transkei (they are often considered a Xhosa sub-group) |

| Southern Ndebele | Southern Ndebele | 659,000 | Central Transvaal |

| [n 2] | |||

| Northern Ndebele (Matabele) | Northern Ndebele | 1,599,000 | Matabeleland Zimbabwe |

| Ngoni | They do not have a language of their own but speak Tumbuka, Chewa, or Nyanja. | 2,044,000 | Malawi Zambia |

| Total | Nguni languages | 28,801,000 | |

Notes

- They are often amalgamated with the Xhosas, for their language too is Xhosa.

- Original Zunda-speaking groups joined by fleeing populations after and during the Mfecane.

Ngoni people by ethnicity are found in Malawi (under paramount Chief Mbelwa and Maseko Paramouncy), Zambia (under paramount chief Mpezeni), Mozambique and Tanzania. In Malawi and Zambia, they speak a mixture of languages of the people they conquered, such as Chewa, Nsenga and Tumbuka.

References

- www.northernndebele.blogspot.com

- "The History of Ancient Nubia | The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago". oi.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2019-11-10.

- Oliver, R. (1966). "The Problem of the Bantu Expansion". The Journal of African History, 7(3), 361-376. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/180108

- Newman, James L. (1995). The Peopling of Africa: A Geographic Interpretation. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07280-8.

- Shillington, Kevin (2005). History of Africa (3rd ed.). New York: St. Martin's Press.

- Russell, Thembi; Silva, Fabio; Steele, James (2014-01-31). "Modelling the Spread of Farming in the Bantu-Speaking Regions of Africa: An Archaeology-Based Phylogeography". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e87854. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...987854R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0087854. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3909244. PMID 24498213.

- Robertson, John H.; Bradley, Rebecca (2000). "A New Paradigm: The African Early Iron Age without Bantu Migrations". History in Africa. 27: 287–323. doi:10.2307/3172118. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3172118.

- "History Of Kruger Park - Iron Age - South Africa..." www.krugerpark.co.za. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- "The story of how livestock made its way to southern Africa". www.wits.ac.za. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Whitelaw, Gavin (2009). "Four Iron Age women from KwaZulu-Natal: biological anthropology, genetics and archaeological context". Southern African Humanities.

- Lander, Faye; Russell, Thembi (2018). "The archaeological evidence for the appearance of pastoralism and farming in southern Africa". PLOS ONE. 13 (6): e0198941. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1398941L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0198941. PMC 6002040. PMID 29902271.

- Killick, David (2014), Archaeometallurgy in Global Perspective, Springer New York, pp. 507–527, doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-9017-3_19, ISBN 978-1-4939-3357-0 Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - Fisher, Erich (2013). "Archaeological Reconnaissance in Pondoland". PaleoAnthopology.

- "Click languages". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-10-26.

- Skhosana, Philemon Buti (2009). "3". The Linguistic Relationship between Southern and Northern Ndebele (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-17.

- "The Mfecane as Alibi: Thoughts on Dithakong and Mbolompo" (PDF). The Journal of African History, Volume 29, Issue 3, Cambridge University Press. 1988. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- Bryant: Olden Times in Zululand and Natal. Ritter: Shaka Zulu