Nesthäkchen in the Children's Sanitorium

Else Ury's Nesthäkchen is a Berlin doctor's daughter, Annemarie Braun, a slim, golden blond, quintessential German girl. The ten-book Nesthäkchen series follows Annemarie from infancy (Nesthäkchen and Her Dolls) to old age and grandchildren (Nesthäkchen with White Hair).[1] This third volume of the series, published 1915/1921, tells the story of ten-year-old Annemarie's bout of scarlet fever, her recovery in a North Sea children's sanitorium, and her desperate struggle to return home at the outbreak of World War I.[2][3]

| |

| Author | Else Ury |

|---|---|

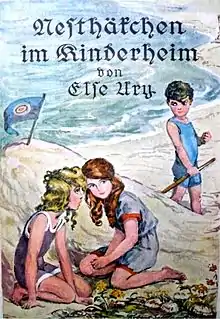

| Original title | Nesthäkchen im Kinderheim |

| Translator | Steven Lehrer |

| Illustrator | Robert Sedlacek |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Nesthäkchen, volume 3 |

| Genre | Fiction/Adventure |

| Publisher | SF Tafel |

Publication date | 2014 |

| Media type | Print (Trade Paper) |

| Pages | 210 pp (Trade Paper edition) |

| ISBN | 1500424587 |

| Preceded by | Nesthäkchen's First School Year |

| Followed by | Nesthäkchen and the World War |

Plot summary

At the beginning of Volume 3 of Else Ury's Nesthäkchen series, Nesthäkchen im Kinderheim, published 1915/1921 (Nesthäkchen in the Children’s Sanitorium), Anne Marie Braun is ten years old. She is a lively child and a good student. Shortly before her birthday, she develops a high fever at school. She has been inadvertently infected with scarlet fever by her father, a doctor in Charlottenburg (Berlin), who has just examined children with scarlet fever. After a long recovery time in the private clinic of her father, Anne Marie is still very weak. Therefore, she is sent by her parents to recover for a year in the children's sanitorium "Villa Daheim" in Wittdün on the North Sea island Amrum, which is managed by a sea captain's widow Mrs. Clarsen and her sister Lina. (The captain's ship was docked in Norddorf, an actual place. There was in Norddorf a port on the Kniepsand side, and also an island railway at that time on Amrum.) Life on the island, the landscape and manners, dress and speech, are described in detail. The North Germans in the story speak Plattdeutsch (Low German), which Ury transliterates, with a German translation of some words in parentheses. Anne Marie makes friends with the naughty boy Peter, who misbehaves again and again. The two walk together to seek wealth and swords in the mud, stray off the path, and get into a storm surge. But they find (albeit with difficulty) their way out of the dangerous situation. Anne Marie befriends a good girl, Gerda. Gerda has a bad leg due to a knee joint problem. Another counterpoint to Peter (who is a replacement for Anne Marie's wild brother Klaus in this part of the novel) is Kurt, whom she already met in Berlin in the hospital. Kurt is in a wheelchair, but manages with much patience and Anne Marie's help, to relearn how to walk. At the end of the story the First World War breaks out. Anne Marie is now eleven years old. Head over heels the sanitorium's guests flee the island. Anne Marie's doll Gerda falls off the pier into the water. The scene has a symbolic meaning: Anne Marie's childhood is over.[4]

Critical reception

"The context of the surrounding social setting is fascinating—a snapshot of a vanished world presented with charming, black-and-white period illustrations. Ury’s narrative tone is amusingly sardonic at times—affectionate but assessing, as it aims to appeal to both children and their parents. Her portraits of the various adults that Annemarie encounters are refreshingly textured; they’re not the one-dimensional authority figures that were more typical of children’s books of the time. The story also handles Annemarie’s shifting emotions, from feeling forlorn to gradually coming to like many people at Wittdün, in a lively, often charming way. It’s easy to see why this series might have been so popular with German families nearly a century ago." Kirkus Reviews[5]

Later revisions

This volume is the most revised of the Nesthäkchen books. In the original, Anne Marie's school year goes by the old count: in the eighth grade she advances to the seventh. In later editions, it is her third year and she advances to her fourth year. In the 1921 edition Anne Marie's friend Gerda was from Breslau, the capital of Lower Silesia. After 1945 Gerda was from Munich, capital of Bavaria. In the original "Princess Heinrich" (that is, Princess Irene of Hesse and by Rhine, 1866–1953, wife of Prince Heinrich, brother of Kaiser Wilhelm II) visited the island and the children's sanitorium. In later editions Princess Heinrich became the young queen of Denmark.[6] A final chapter, “War Time,” added after 1945 to maintain continuity of the series after volume 4 was dropped, was a politically correct abridgement of the original version of Volume 4, Nesthäkchen and the World War. The further course of the First World War is reduced to, "However, the terrible war had ended a short time later." Anne Marie's girlfriend Vera, who appears in Volume 4, is introduced in the new chapter with a few words. Vera's oppressive history, a chilling example of relational aggression that is left out, is not only one of the most important and most instructive episodes in Anne Marie's life, but also one of Ury's major literary achievements (see Nesthäkchen and the World War). By 1996 the publisher had dispensed with the new chapter "War Time," and the story ends, as it did in 1921, with Annemarie's return to her home in Berlin. [7][8]

Genre

The Nesthäkchen books represent a German literary genre, the Backfischroman, a girls' novel that describes maturation and was intended for readers 12 - 16 years old. A Backfisch (“teenage girl”, literally “fish for frying”) is a young girl between fourteen and seventeen years of age. The Backfischroman was in fashion between 1850 and 1950. It dealt overwhelmingly with stereotypes, traditional social images of growing girls absorbing societal norms. The stories ended in marriage, with the heroine becoming a Hausfrau. Among the most successful Backfischroman authors, beside Else Ury, were Magda Trott, Emmy von Rhoden with her Der Trotzkopf and Henny Koch. Ury intended to end the Nesthäkchen series with volume 6, Nesthäkchen Flies From the Nest, describing Nesthäkchen's marriage. Meidingers Jugendschriften Verlag, her Berlin publisher, was inundated with a flood of letters from Ury's young fans, begging for more Nesthäkchen stories. After some hesitation, Ury wrote four more Nesthäkchen volumes, and included comments about her initial doubts in an epilogue to volume 7, Nesthäkchen and Her Chicks.

Author

Else Ury (November 1, 1877 in Berlin; January 13, 1943 in the Auschwitz concentration camp) was a German writer and children's book author. Her best-known character is the blonde doctor's daughter Annemarie Braun, whose life from childhood to old age is told in the ten volumes of the highly successful Nesthäkchen series. The books, the six-part TV series Nesthäkchen (1983), based on the first three volumes, as well as the new DVD edition (2005) caught the attention of millions of readers and viewers.[9][10]

References

- Jennifer Redmann. Nostalgia and Optimism in Else Ury's "Nesthäkchen" Books for Young Girls in the Weimar Republic. The German Quarterly, Vol. 79, No. 4 (Fall, 2006), pp. 465-483

- Nesthäkchen in the Children's Sanitorium on Google Books

- Nesthäkchen in the Children’s Sanitorium in the Library of Congress catalog

- Steven Lehrer. Introduction to Nesthäkchen and the World War. iUniverse 2006

- Kirkus Review of Nesthäkchen in the Children's Sanitorium

- Pech, Klaus-Ulrich: Ein Nesthaken als Klassiker. Else Urys Nesthäkchen-Reihe. In: Klassiker der Kinder- und Jugendliteratur. Edited by Bettina Hurrelmann. Fischer Verlag. Frankfurt/M. 1995, pp 339 – 357

- Marianne Brentzel. Nesthäkchen kommt ins KZ. FISCHER Taschenbuch; Auflage: 1., Aufl. (März 2003)

- Barbara Asper. Wiedersehen mit Nesthäkchen: Else Ury aus heutiger Sicht. TEXTPUNKT Verlag; Auflage: 1., Aufl. (1. November 2007)

- Patricia M. Mazón. Gender and the Modern Research University: The Admission of Women to German Higher Education, 1865-1914. Stanford University Press; 1 edition (August 4, 2003) pp 166-175

- Melissa Eddy. Overlooked No More: Else Ury’s Stories Survived World War II. She Did Not. NY Times July 10, 2019