Nels Johnson

Nels Johnson (1838–1915) was a Danish-American professional mechanic and engineer who made and repaired nineteenth century machinery as various businesses. Having learned his basic skills as a blacksmith in Europe, he immigrated to the United States and worked as a clockmaker that made grandfather type tall clocks and tower clocks in Manistee, Michigan. He was the manufacturer of Century tower clocks (guaranteed for 100 years) that were tower clocks put in businesses, government buildings, churches, and courthouses throughout the world. He was also a scientist that worked with astronomy.

Nels Johnson | |

|---|---|

photograph, circa 1885 | |

| Born | Nels Johnson November 26, 1838 |

| Died | January 13, 1915 |

| Resting place | Oak Grove Cemetery in Manistee, Michigan. |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Occupation | clockmaker |

| Employer | Century Tower Clocks |

| Known for | tower clocks |

| Children | four |

| Parent(s) | father: Jorgen Neilsen mother: Ana Marie Sorensen |

Biography

Early life

Johnson was born in Nordrup (near Skaftelev in Slagelse Municipality on the island of Zealand), Denmark, about 50 miles from Copenhagen on November 26, 1838.[1] His father was Jorgen Neilsen and his mother was Ana Marie Sorensen. His parents owned a farm of 3 acres (1.2 ha) that was cultivated for an income. Danish custom was for a boy's given last name to be obtained from the father's name, therefore the son of Jorgen becomes Jorgenson as the new family name.[2] He anglicized his Danish last name of Jorgenson to Johnson after his arrival in America.[3]

Johnson was the oldest child of a poor family and had five siblings. He was kicked out of the blue-collar working family when he was seven years old since his parents could no longer support a large family. He had to support himself by working for other farmers, caring for sheep, geese, and cattle.[4] He wore wooden shoes in the winter and was barefoot in the summer months. Johnson, like many other young boys, wanted to become an organ grinder with a monkey. He also wanted to travel with a circus or to be a bugler or drummer boy in the army or to see the world as a sailor. His parents wanted him to become a shoemaker. Ultimately, he decided to become a blacksmith and was apprenticed to a local shop working fourteen hours a day.[5][6]

Mid life

Nels left the Denmark area to "see the world" when he was about fourteen years old. He hitchhiked rides to Copenhagen where he hoped to join the army. Since the army would not accept him, he went to work for a farmer for $23 a year including boarding. After a year he decided he had enough of that and then got a job in a beer brewery cleaning bottles. He also delivered beer for the company, on foot. When he was fifteen he got a job in a restaurant in Tivoli, doing miscellaneous labor assignments and delivering meals to families, again on foot. That job soon ended, so he walked some 40 miles to another city and went to work moving paving stones with a wheelbarrow. His food was coarse rye bread with water and he slept on straw for a bed in a barn and covered himself with a horse blanket for warmth.[6]

When he was sixteen, in the spring of 1855, he went back to Copenhagen. There he found an apprenticeship to a blacksmith in the Danish city of Randers. The apprenticeship was for six years. He earned $16 per year, which included housing. He worked 14-hour days from sunrise to sunset. Mealtimes were just enough time to have a quick meal. The work was pumping bellows for the main blacksmith and pounding on heavy forgings with a sledge hammer. The work was basically on large windmills. He completed his apprenticeship when 23 years old in 1861.[6]

Johnson was then drafted into the army in the spring of that year. He trained in boot camp for four months. He was then permitted to return home as a "free shooter" in the army reserve. He returned to Randers and got a job. Two years later in 1863 the army reserves were called. There was fear that war was going to break out between Denmark and Germany. He then left Randers and went to Hamburg, Germany. There he used most of his small savings to buy a ticket to Liverpool, England. Upon entering the ship going to England he discovered he needed a passport. Not having one he improvised and posed as a working shepherd when several hundred sheep were being loaded on the boat to go to Hull, England. When he was on board the boat he disappeared and found a place to hide so as not to get caught until the ship was on its way. Johnson then came across a group of 100 Danish immigrants who were on their way to America by way of Liverpool. Scandinavians by the droves were going to America in the 1860s. Johnson figured that perhaps there would be better opportunities in America so decided to emigrate to America. The man in charge of the group that went to a Liverpool hotel on May 11th was Rasmus Sorensen.[6]

Johnson talked to Sorensen while at the hotel for a couple of days and asked for help to go with the immigrants as far as Quebec. He told him that he was a blacksmith and his ticket took him only to Liverpool. Sorensen agreed to the request and they negotiated an agreement where Johnson would pay back the cost of transportation. They left Liverpool to America on May 14th on board the steamboat Hebernian and Sorensen had given Johnson a ticket to Quebec.[6] Sorensen had paid $36 in gold for the passage and told Johnson that he felt confident that he would ultimately get paid back since he trusted him.[6] In effect Johnson was a stowaway when they went to Quebec in 1863. He had only twenty-five cents in his pocket when they arrived in Quebec eleven days later on May 25. He somehow then managed to get a free train ticket from Quebec to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. From Quebec he went on the Grand Trunk Railroad bound for Detroit and arrived midday on May 29. In the evening he left there bound for Grand Haven, Michigan. He arrived there at 6 a.m. the next morning. That day he got on board a lake steamer from Grand Haven to cross Lake Michigan and arrived in Milwaukee on Sunday May 30, 1863. He found work and repaid Sorensen as soon as he could.[6]

Johnson became a blacksmith for a year or two while in Milwaukee, a trade he learned as a boy.[7] From about 1863 and until 1871 he worked in a machine shop there. He was a skilled mechanic and was promoted from time to time and eventually achieved a top position within a firm.[1][8] While still in Milwaukee he formed a partnership machine shop with John Bowie on May 1, 1871. They decided to move to Manistee, Michigan, and open their own machine shop and foundry there. They dismantled their machine shop and boxed it up piece by piece in crates. They then shipped everything to Manistee on a lake schooner. Johnson first put his wife and children, along with his horse and wagon, on a boat and sailed with them across Lake Michigan to Manistee on May 31, 1871. Bowie with their equipment went on another boat and arrived the next day. By mid-afternoon they were constructing their new shop and foundry. By June 23 it was operational and they sold their first service. On June 26 Johnson sold his first cash product which was a nut for an axle which he sold for sixty cents.[6]

October 8 of that year brought a devastating fire to Manistee and his shop, which happened coincidentally at the same time as the 1871 Great Chicago Fire. Johnson and Bowie lost everything, their shop, their $9,000 business and their partnership turned bad. Johnson wound up selling off his share of the partnership to a Mr. Stoke for $1,000. An Odd Fellows Lodge in Milwaukee sent Johnson $100 to help out his family. Johnson was able to buy a lot and lumber with the amount of money he had. He then rebuilt the machine shop and an economical 14 foot by 20 foot structure to live in. The cheap wet lumber used for his dwelling warped and caused gaps in their housing structure. It was by no means weather proofed and rain and snow came through. Through determination and persistence he eventually got himself back on track and after a couple of years he was able to save up enough money to build a small house for the family.[6][8]

Later life

O. E. Wheeler became interested in what Johnson was doing and they formed a partnership in January 1872. Wheeler was a commercial shipper and owned tug boats. Soon their business of Wheeler & Johnson developed a specialty of repairing and building sawmill machinery. They also built shingle-mills as a speciality with a crew of twelve to fifteen men. Within a few years, the business outgrew the small machine shop they started. They then built a new brick building with a slate roof, designed to resist any windblown sparks in case of another town inferno. Soon afterwards they built a second brick building next to the first one. It was ultimately intended for tower clock manufacture.[1][8]

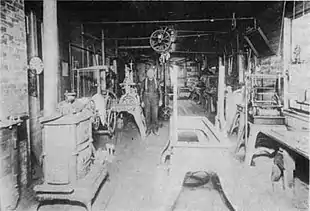

James Shrigley became a third partner in 1880 buying 1/3 interest into the business, changing the name to Wheeler, Johnson & Company. Among the products that the machine shop made were railroad castings and a hoop splitter invented by Johnson and used by barrel makers. The shop also made repairs to railroad equipment, sawmill equipment, and salt well equipment (Manistee is sometimes called "the salt city"). Later their shop began making gasoline engines and gasoline marine engines. Their machine shop business had a machine shop with many large machines and tools, a blacksmith shop, a pattern shop, an iron and brass foundry, and an office. The business prospered for many years until Johnson bought out his partners in 1893. In 1895 Johnson decided to sell the machine shop business to one of his sons, August N. Johnson. He kept the clock manufacturing shop.[1][8]

Clock making

Johnson found time to study the mathematical relations of clock movements while he was running his machine shop business. He purchased a second-hand clock and studied its mechanism thoroughly. It is likely that his first actual clock work began around 1865 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He made at least one electric clock, while still in Milwaukee. Johnson's real interest and motivation was while he lived in Michigan. He was most serious about clock making after he moved to Manistee. There are no records of how many non-tower clocks Johnson actually made. One Manistee man, John Pershbacher, who is knowledgeable about antiques and operates a local museum, said he has seen fifteen. In all likelihood there are over 25, according to clock historian Jack Linahan.[6][8]

He built four grandfather clocks for his four children about 1879. They were in eight foot wooden and glass cases. Johnson then in the mid-1880s started to make tower clocks using his mechanical skills he acquired along the way and knowledge and understanding he had acquired in horology.[8]

Johnson took on another partner named McGrath about 1887 strictly for financial reasons. Then he "split" the business retaining the "heavy part" for Wheeler and formalizing the clock part with McGrath. Johnson, however, had control over both businesses. The clock manufacturing part was run only by Johnson - it was strictly a one-man operation. Johnson broke the partnership with McGrath on May 26, 1892.[6] His first real order for a large tower clock was for a business clock in downtown Manistee about 1888. His reputation for quality tower clocks for businesses spread and he soon was receiving other orders for his Century tower clocks for churches, government buildings and courthouses. His tower clocks were guaranteed to operate for 100 years if properly maintained.[8]

The idea came to Johnson to make a couple of clocks with sufficiently uniform pendulums that they would beat synchronously, however he was not able to accomplish this. He presented this problem to science professors at the University of Michigan. They pointed out to Johnson that it was impossible. The subject of astronomy came up in their talks and the part the stars play in the determining of correct time. The professors loaned books on mathematics and astronomy to Johnson. He mastered algebra, geometry, trigonometry, and basic astronomy. In 1887 he met a Professor Harrington of Ann Arbor, Michigan. The professor taught him that no two clocks could be made to run synchronously independent on their own to where they ran at exactly the same time on the same beat and swing of the pendulums. He explained that the only way to arrive at the correct time was to use fixed stars. The stars could be seen by the use of a transit telescope. In 1889 Johnson bought one so he could observe stars in getting accurate readings for time measurements. He was able to receive assistance in his more complicated mathematical calculations from Professor William Hussey, an astronomer at Stanford University.[1][8]

Personal life

Johnson was married to Frances Green in 1865 at Milwaukee. Their first child born in 1869 was named August Nel. They had another child, Henrietta (Hattie), by 1871. They had four more children while living in Manistee, Michigan. One was a daughter named Clara, born March 15, 1877, but died at the age of six on June 8, 1885. August, Dollie, Katherine, and Nels Jr. reached adulthood and married. Nels' first wife, Frances, died on June 11, 1880, at the age of 39. He got remarried to Amanda Golden in 1881. Amanda died in 1917, two years after Nels' death. Nels, Frances, Amanda, Clara, and Nels' mother's gravesites are at the Oak Grove Cemetery in Manistee, Michigan.[6]

Johnson at the age of 76 died in Manistee January 20, 1915.[9]

References

- RPC 1895, pp. 185-187.

- Murray 1888, p. 563.

- Devon Frances (1966). "A Rare Experience". NAWCC Bulletin. 28: 631–640.

- Nicholson 2013, p. 99.

- Leonard Lanson Cline (1915). "The Builder of Fifty Tower Clocks". American Magazine. 79: 54–55.

- Jack Linahan (2006). "Nels Johnson, Michigan clockmaker". NAWCC Bulletin. 48: 391–401.

- "He Makes Fine Clocks". Detroit Free Press. Detroit, Michigan. July 7, 1901. p. 30 – via Newspapers.com

.

. - Dana J. Blackwell (1964). "Nels Johnson and his Century tower clocks". NAWCC Bulletin. 108: 82–89.

- "Manistee". Livingston County Daily Press. Howell, Michigan. January 20, 1915. p. 8 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

Sources

- Murray, James Augustus Henry (1888). English Dictionary Historical Principles. Clarendon Press. OCLC 1068304435.

- Nicholson, Howard L. (2013). Danes and Icelanders in Michigan. Michigan State University Press. ISBN 9781628950397.

- RPC (1895). Portrait & biographical record Northern Michigan. Record Publishing Company. OCLC 1048537921.