Neisseria flavescens

In 1928, Neisseria flavescens was first isolated from cerebrospinal fluid in the midst of an epidemic meningitis outbreak in Chicago.[2] These gram-negative, aerobic bacteria reside in the mucosal membranes of the upper respiratory tract, functioning as commensals.[3] However, this species can also play a pathogenic role in immunocompromised and diabetic individuals.[4] In rare cases, it has been linked to meningitis, pneumonia, empyema, endocarditis, and sepsis.

| Neisseria flavescens | |

|---|---|

| |

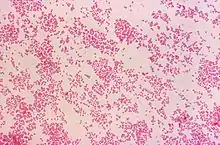

| A gram stain of Neisseria flavescens provided by CDC/Dr. W. A. Clark | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | N. flavescens |

| Binomial name | |

| Neisseria flavescens Branham 1930[1] | |

Morphology

These bacteria are gram-negative and diplococcus, rendering them virtually indistinguishable from the other Neisseria species.[2] Yet, Neisseria flavescens remains distinct due to its signature pigmented colonies, yellow-gold in color.[5] And it is through this yellow-gold color that this bacteria earned its name, with flavescens precisely translating as "becoming a golden yellow."[2] This pigmentation also indicates N. flavescens' similarity to saccharolytic Neisseria species, which also exhibit pigmentation.[6] In addition, these pigmented species differ from meningococcus, which lack pigmentation.[2]

Biochemical processes

Similar to saccharolytic species, N. flavescens strains are capable of producing polysaccharides from sucrose and are colistin-susceptible.[6] This bacteria is also catalase and oxidase positive.[3] It is not capable of acid-production from glucose, maltose, fructose, sucrose, mannose, or lactose, in contrast to meningococcus, which are active-fermenters.[2] Furthermore, fundamental differences between these two species are again shown, as serological testing reveals N. flavescens' lack of cross-agglutination.[2] At the same time, biochemical testing distinguishes Neisseria flavescens from other gram-negative diplococci, with N. flavescens being DNase negative, weakly positive to Superoxol, and capable of prolyl aminopeptidase production in an enzyme-substrate test.[5]

Molecular biology

Though it shares many similarities with the saccharolytic species, Neisseria flavescens has a greater genetic relation to pathogenic Neisseria species,[6] as molecular studies have shown.[7] In addition, studies implicate that this species plays a role in penicillin-resistant strains of Neisseria meningitidis. The increasing selective pressure from penicillin treatment has led to N. meningitidis' uptake of an altered penicillin-binding protein gene, penA, from Neisseria flavescens via transformation.[8] This modified penicillin-binding protein, also known as mecA, inhibits Neisseria meningitidis' transpeptidases from binding to the β-lactam portion of penicillin.

Disease

Typically serving as a commensal, Neisseria flavescens has also played a pathogenic role, ever since its origin. Arising from an epidemic meningitis outbreak in Chicago, N. flavescens was isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of infected individuals. In particular, out of forty-seven total cases of meningitis, fourteen individuals were found to carry N. flavescens, in contrast to carrying one of the typical four meningococci.[2] Additionally, the mortality rate among these fourteen individuals was close to thirty percent, indicating that this bacterium's role as a possible causative agent for meningitis should not be overlooked.[2] Since then, four other cases of meningitis have also found Neisseria flavescens to be the causative agent.[9]

Along with meningitis, this organism has also been linked to sepsis following surgery.[9] A patient presented with clinical signs typical of meningococcal-strains: fever, chills, headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and skin rash.[9] To identify the causative agent, smears from skin lesions and blood cultures were obtained from the patient.[9] Gram-negative, diplococci were present in the smear, narrowing the organism down to a Neisseria species. Ultimately, blood cultures revealed N. flavescens to be the culprit, due to observation of yellow-gold colony formation and no sugar fermentation.[9]

In addition to blood and CSF, Neisseria flavescens can also act as a pathogen in the lower respiratory tract.[4] Isolation via a transthoracic pulmonary fine-needle aspiration identified N. flavescens as the cause of pneumonia and empyema in a diabetic patient.[4] More specifically, the aspirate was sent off to the respiration department, where it underwent acid fast and gram staining, inoculation, and biochemical testing to identify N. flavescens.[4] Next, 16S rRNA sequencing was done, further confirming that Neisseria flavescens was indeed the causative agent.[4]

Lastly, this bacteria has also been the pathogen behind a case of endocarditis. Testing β-lactamase positive, Neisseria flavescens rendered penicillin an ineffective treatment for the patient and, instead, was targeted by cefotaxime.[10]

References

- LPSN lpsn.dsmz.de

- Branham, Sara E. (1930-04-18). "A New Meningococcus-like Organism (Neisseria flavescens n. sp.) from Epidemic Meningitis". Public Health Reports. 45 (16): 845–849. doi:10.2307/4579618. JSTOR 4579618.

- "What does Neisseria flavescens mean? Definition, meaning and sense (The Titi Tudorancea Encyclopedia)". www.tititudorancea.com. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- Huang, Ling; Ma, Lan; Fan, Kun; Li, Yang; Xie, Le; Xia, Wenying; Gu, Bing; Liu, Genyan (2014-05-01). "Necrotizing pneumonia and empyema caused by Neisseria flavescens infection". Journal of Thoracic Disease. 6 (5): 553–557. doi:10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.02.16. ISSN 2072-1439. PMC 4015020. PMID 24822118.

- "Neisseria flavescens - Gonorrhea - STD Information from CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- http://cmr.asm.org/content/1/4/415.full.pdf

- HOKE, C.; VEDROS, N. A. (1982). "Taxonomy of the Neisseriae: Deoxyribonucleic Acid Base Composition, Interspecific Transformation, and Deoxyribonucleic Acid Hybridization". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 32 (1): 57–66. doi:10.1099/00207713-32-1-57.

- Spratt, B G; Zhang, Q Y; Jones, D M; Hutchison, A; Brannigan, J A; Dowson, C G (1989-11-01). "Recruitment of a penicillin-binding protein gene from Neisseria flavescens during the emergence of penicillin resistance in Neisseria meningitidis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 86 (22): 8988–8992. Bibcode:1989PNAS...86.8988S. doi:10.1073/pnas.86.22.8988. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 298417. PMID 2510173.

- Wertlake, Paul T.; Williams, Temple W. (1968-07-01). "Septicaemia caused by Neisseria flavescens". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 21 (4): 437–439. doi:10.1136/jcp.21.4.437. ISSN 0021-9746. PMC 473828. PMID 4972296.

- Sinave, Christian P.; Ratzan, Kenneth R. (1987). "Infective endocarditis caused by Neisseria flavescens". The American Journal of Medicine. 82 (1): 163–164. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(87)90399-8. PMID 3799678. Retrieved 2015-11-28.