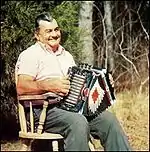

Nathan Abshire

Nathan Abshire (June 27, 1913 – May 13, 1981) was an American Cajun accordion player who was partially responsible for spread of the accordion in Cajun music. His time in the U.S. Army inspired Abshire to write the crooner song "Service Blues", which the newspaper Daily World reported as "one of his most memorable tearjerkers". After the war, he settled in Basile, Louisiana, where he played regularly at the Avalon Club. He released his best-known record, "Pine Grove Blues", in 1949. Abshire's music became more well-known outside outside of Louisiana at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival. Abshire was never able to write so he was unable to sign autographs, resulting in him having to politely decline the requests. Despite thoughts of Abshire being "arrogant or stuck-up" for not signing autographs, he was unable to read and write. However, Abshire was taught how to write his own signature by Barry Jean Ancelet. Despite receiving more income from music than the majority of Cajun musicians, Abshire was not able to entirely depend on that income to live on. Abshire had multiple jobs during his life and his final job was working as the custodian of the town's dump. Abshire's legacy continued after his death in the form of a museum, a book, and a magazine special issue.

Nathan Abshire | |

|---|---|

Nathan Abshire | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Nathan Abshire |

| Born | June 27, 1913[1] Gueydan, Louisiana, U.S[1] |

| Died | May 13, 1981 (aged 67)[1] Basile, Louisiana, U.S |

| Genres | Cajun music, swamp blues, Louisiana blues |

| Occupation(s) | Accordion player |

| Years active | 1930s–1981 |

| Labels | Bluebird Records, O.T. Records, Khoury Records, Swallow Records |

After Abshire's wife declined to have his accordion on display at the Smithsonian Institution in 1983, the accordion was displayed at the Cajun Music Hall of Fame in Eunice, Louisiana in 1996. In 1984, a book titled The Makers of Cajun Music featured Abshire among the musicians. Abshire's former home was made into a renovated museum while also being moved to nearby Basile City Hall. In 2013, the fall edition of the magazine Louisiana Cultural Vistas had 8 pages about "Abshire's life, his love, and his music".

Personal life and career

Abshire was born on June 27, 1913, close to Gueydan, Louisiana. He was considered illiterate and he had trouble speaking English.[2] Learning the accordion at age six, Abshire was influenced by his father, mother, and uncle who all played the accordion.[3] Abshire first performed on the accordion in public at age eight. When he was 8 years old, Abshire was considered to be an "accomplished musician" due to learning how to play an accordion that costs $3.50.[2]

He was also influenced by the musician Amédé Ardoin. In an interview, Abshire said, "Every Saturday afternoon some years ago, we used to go to John Foreman's saloon. I'd see Amédé Ardoin coming full-stride down the way. He'd say, "Abshire, you've got to help me tonight."[4]

In the 1930s, he performed with and learned from fiddler Lionel Leleux and accordionist Ardoin.[5] In 1935, he recorded six songs with the Rayne-Bo Ramblers, a group led by guitarist and singer Leroy "Happy Fats" Leblanc.[6] He also played with the Rayne-Bo Ramblers again in the 1960s.[2]

Abshire served in the U.S. Army during World War II which stopped him from playing the accordion.[2][7] He was discharged from the military after he broke his leg while training.[5] His time in the army inspired Abshire to write the crooner song "Service Blues", which the newspaper Daily World reported as "one of his most memorable tearjerkers". In "Service Blues", "Abshire crooned about waiting alone at the train station, set to leave all that he loved in Louisiana".[2]

After the war, he settled in Basile, Louisiana, where he played regularly at the Avalon Club. He released his best-known record, "Pine Grove Blues", in 1949,[8] a song based on Amede Breaux's "Le Blues de Petit Chien",[9] as well as several recordings on Swallow Records and Arhoolie Records in the 1960s. He appeared with Dewey Balfa and The Balfa Brothers at the Newport Folk Festival in 1964.[3] Abshire's music became more well-known outside outside of Louisiana at the 1964 Newport Folk Festival.[10] Along with Balfa, Abshire devoted much of his time in the 1960s and 70s to promoting Cajun music through appearances at festivals, colleges, and schools throughout the United States.[3]

At some point, Abshire declined to perform with Hank Williams. In 1970, Abshire played with the Balfa Brothers at the University of Iowa in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. It was their first tour and they wanted to "prove that Cajun music still exists - in its traditional form - and to save what's left".[10]

Abshire was never able to write so he was unable to sign autographs, resulting in him having to politely decline the requests. Despite thoughts of Abshire being "arrogant or stuck-up" for not signing autographs, he was unable to read and write. Abshire considered his inability to do those things as frustrating and humiliating. Abshire learned how to write a signature from Barry Jean Ancelet and his signature used "stick figure letters" to sign "N A". Abshire also used the signature for legal documents.[11]

Despite receiving more income from music than the majority of Cajun musicians, Abshire was not able to entirely depend on that income to live on. Abshire had multiple jobs during his life and his final job was working as the custodian of the town's landfill. He took used objects from his yard to sell on his front porch.[4]

Abshire was featured in Les Blank's 1971 documentary Spend It All and the 1975 PBS documentary, The Good Times Are Killing Me.[12] He was also included in the documentary film, Les Blues de Balfa, along with Balfa. The documentary was first released on VHS in 1993 and its English translation is Cajun Visits: Filmed At Their Homes.[13]

Death and legacy

He died in Basile, Louisiana on May 13, 1981 at Savoy Memorial Hospital in Mamou after a long illness.[14] Shortly before he died, Abshire came back from the New Orleans Heritage Fair and was invited to an accordion festival in Brussels, Belgium.[15] Abshire's funeral service was held at St. Augustine Catholic Church in Basile.[14] He was buried in the church's cemetery.[15] Abshire said prior to his death, "When I die, I wish they would break all my records and not play them anymore. It doesn't feel right for the radios and everyone to keep on playing a musician's music after he's gone."[16] Abshire also wanted his music to be buried with him, but that never happened.[17] A benefit was held for Abshire's family on June 28, 1981, in which multiple Cajun musicians performed. A benefit dance was held at the Knights fo Columbus Hall in Basile and the musicians that played during the dance changed each hour.[18]

In September 1981, a commemorative print of Abshire performing live was sold in The Kinder Courier News. There were 350 pen and ink prints available that could be framed.[19] The Louisiana newspaper Basile Weekly said in 1983, "Despite the efforts of many this great Cajun musician fell short of receiving the recognition and credit due him for his contributions to Cajun music and the preservation of our Acadian Culture". A tribute was held for Abshire on August 21, 1983 in Basile, Louisiana at the city park. Performers played music during the tribute. Basile mayor Joe Toups proclaimed August 21, 1983 as Nathan Abshire day for his work in preserving Acadian culture.[20] In 1984, a book titled The Makers of Cajun Music featured Abshire among the musicians.[16] In 1983, Abshire's wife refused to have his accordion on display at the Smithsonian Institution.[17]

In 1995, the newspaper Daily World said, "Bands are still recording Abshire's signature tune, "The Pine Grove Blues", which has also become a favorite among line dancers. Other songs like "The Bayou Teche Waltz", "French Blues", "Belezare's Waltz" and "The Chopique Two Step" remain top favorites". In 1995, a show on KSLO (AM) titled "The Yamland Fais Do Do" played much of Abshire's music.[2] In 1996, the Cajun Music Hall of Fame in Eunice, Louisiana acquired Abshire's accordion.[17]

In the late 1990s, there was an idea to turn Abshire's former home into a museum and in February 2004, Basile mayor Berline B. Boone-Sonnier stated that she wanted it to happen. Sonnier transported the home to nearby Basile City Hall and part of the home was renovated.[21] The museum was later built and Santa visits were held there.[22]

Sheryl Cormier, "the first Cajun female accordion recording artist", stated in 2002 that she was influenced by Abshire, Aldus Roger, and Lawrence Walker.[23] In 2013, the fall edition of the magazine Louisiana Cultural Vistas had 8 pages about "Abshire's life, his love, and his music".[24]

See also

- History of Cajun Music

- List of Notable People Related to Cajun Music

References

Footnotes

- Woodstra, Chris; Erlewine, Stephen Thomas; Bogdanov, Vladimir; Erlewine, Michael (1997). All Music Guide to Country: The Experts' Guide to the Best Country Recordings (1st ed.). Backbeat Books. p. 1. ISBN 978-0879304751.

- "Nathan Abshire is an inspiration to Cajun musicians". Daily World. Opelousas, Louisiana. May 18, 1995 – via Newspapers.com.

- Ancelet, Barry Jean (1999). Cajun and Creole Music Makers: Musiciens cadiens et créoles (2nd ed.). University Press of Mississippi. p. 101. ISBN 978-1578061709.

- Bradshaw, Jim (August 29, 2010). "Nathan Abshire made music, legends". Abbeville Meridional. Abbeville, Louisiana – via Newspapers.com.

- Hahn, Roger. "Nathan Abshire". Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- Bush, John. "Nathan Abshire". Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- Henderson, Lol; Stacey, Lee (1999). Encyclopedia of Music in the 20th Century. Routledge. p. 8. ISBN 978-1579580797.

- "Nathan Abshire & the Pine Grove Boys - French Blues". Archived from the original on 2014-08-19. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- Caffery, Joshua Clegg (2013). Traditional Music in Coastal Louisiana: The 1934 Lomax Recordings. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0807152010.

- Zielinski, Mary (February 8, 1970). "Iowans Hear Cajun Sound In Music of Belfa Brothers". The Gazette. Cedar Rapids, Iowa – via Newspapers.com.

- Thibodeaux, William (March 19, 2013). "Nathan's Mark". Abbeville Meridional. Abbeville, Louisiana – via Newspapers.com.

- Boyle, Deirdre (1997). Subject to Change: Guerrilla Television Revisited (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 148. ISBN 978-0195110548.

- "Cajun visits ; Les Blues de Balfa". WorldCat. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- "Services Held Friday For Nathan Abshire". Basile Weekly. Basile, Louisiana. May 20, 1981 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Nathan Abshire, Accordionist Dies". Daily World. Opelousas, Louisiana. May 14, 1981 – via Newspapers.com.

- "New Book Features Cajun Musicians". Basile Weekly. Basile, Louisiana. October 25, 1984 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Kinder's Gene Allemand lending Abshire's accordion to museum". The Kinder Courier News. Kinder, Louisiana. October 3, 1996 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Benefit Planned For Nathan Abshire Family". The Crowley Post-Signal. Crowley, Louisiana. June 21, 1981 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Announcing". The Kinder Courier News. Kinder, Louisiana. September 3, 1981 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Nathan Abshire Day Sunday". Basile Weekly. Basile, Louisiana. August 18, 1983 – via Newspapers.com.

- Burgess, Richard (February 22, 2004). "Cajun musician's home revived". The Daily Advertiser. Lafayette, Louisiana – via Newspapers.com.

- "Santa visits Basile at Nathan Abshire Museum". Basile Weekly. Basile, Louisiana. December 21, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Acadian Museum names Cormier a 'Living Legend'". Abbeville Meridional. Abbeville, Louisiana. March 6, 2002 – via Newspapers.com.

- LeJeune, Darrel (October 10, 2013). "Nathan Abshire featured in La. Cultural Vistas magazine". Basile Weekly. Basile, Louisiana – via Newspapers.com.

Sources

- American National Biography, vol. 1, pp. 48–49.

- American National Biography, vol. 3 pp. 38–39.