Murder of Diana Quer

In the early hours of 22 August 2016, an 18-year-old woman named Diana Quer went missing in the small town of A Pobra do Caramiñal in Galicia, Spain. The case went unsolved for over a year and received significant media attention. In December 2017, a 41-year-old man named José Abuín or "El Chicle" confessed to the murder of Quer while being interrogated for an attack on another woman, and revealed the location of the body. "El Chicle" was found guilty on 17 December 2019 of aggravated murder, and received life imprisonment.[1]

Background

Diana María Quer López-Pinel[2] (born 12 April 1998)[3] was from Pozuelo de Alarcón in the Community of Madrid and was on holiday with her mother and sister.

Quer was left by her mother at 10:30 pm and went to a local festival. Her last known location was a kilometre from home, at around 2:50 am. Among her final WhatsApp messages were to a friend from Madrid: "I'm freaking out, a gypsy was calling for me...[He was saying] 'brown-haired girl, come over here'".[2]

Investigation

Two hundred local men who were aged in their late 30s and had criminal records were interviewed by police over the case. This was later reduced to 80 of them whose mobile phone records confirmed that they were in the vicinity of the crime. Among these was the perpetrator José Enrique Abuín Gey or "El Chicle", who had a previous conviction for cocaine dealing. He was given a false alibi by his wife, who said that they were with each other at the time.[4] In October 2016, a fisherman found Quer's iPhone 6 in nearby Taragoña.[5]

In the early hours of 25 December 2017, El Chicle attempted to invite several young women into his car in nearby Boiro. He tried to force one into the boot of his car at knifepoint, but her screams drew attention.[6] During his interrogation, he confessed to killing Quer; he tied her up and took her into his car by force and strangled her. He revealed the location of the body, in a well at an abandoned warehouse in Rianxo, 20 kilometres from the location of the crime and only 200 metres from his own house.[7]

Trial

After four days of deliberation, the jury at Santiago de Compostela unanimously found El Chicle guilty of murder. A life sentence was ordered due to aggravating factors of premeditation, sexual motive and motive of hiding a previous crime. While a sexual motive was proven, the jury cleared him of attempted rape.[1] He also received a further four and a half years for kidnap and sexual assault of Quer, and five years for the attempted kidnap in Boiro.[1] He was fined €130,000 to each of Quer's parents and €40,000 to her sister, as well as legal costs.[1]

El Chicle was held at the A Lama and Teixeiro prisons in Galicia, but was moved to Villahierro near León to avoid reprisals from former associates and rivals from the cocaine trade.[8] His prison mail showed no sign of repentance, and attempted to implicate his ex-wife in the murder.[8] He became socially dominant at Villahierro, where his fellow inmates included David Oubel, another Galician from Moraña, who was the first person sentenced to life imprisonment since the sentence was reintroduced in 2015.[8]

Media coverage

The missing person case and subsequent murder trial received a large amount of media coverage. Some news outlets were criticised for relying on morbid fascination or sensationalism in their coverage.[9][10] One cited example was the Espejo Público ("Public Mirror") programme on Antena 3, which reported that Quer's social media account was still active and speculated as to why.[9] The same programme was condemned by Quer's family in October 2019 for broadcasting an alleged "last photograph" of the murder victim; the relatives believed that it was implying that her clothing was responsible for her death.[11]

Some authors believed that the case had disproportionate coverage as Quer was young, wealthy and female (see Missing white woman syndrome).[12][13] One case contrasted with that of Quer was of Iván Durán, a 30-year-old man from nearby Baiona, who went missing three days later. Durán's father said that police resources went disproportionately to the search for Quer.[14] An autopsy indicated that Durán committed suicide by firearm shortly after leaving home.[15]

Legacy

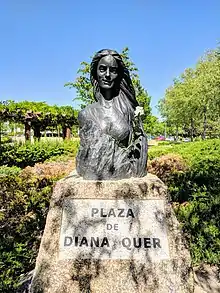

In November 2018, a sculpture of Quer was unveiled at a square named after her in her hometown of Pozuelo de Alarcón.[16]

References

- Puga, Natalia (17 December 2019). "El Chicle condenado a prisión permanente revisable por la muerte de Diana Quer" [El Chicle sentenced to permanent revisable prison for the death of Diana Quer]. El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Durán, Luis F. (26 August 2016). "La joven madrileña desaparecida alertó en un whatsapp a un amigo de que alguien la perseguía" [The young missing woman from Madrid alerted a friend on WhatsApp that somebody was following her]. El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- "El emotivo mensaje de Juan Carlos Quer a Diana en su cumpleaños: "Vives en el corazón de tus padres y hermana"" [Juan Carlos Quer's emotional message to Diana on her birthday: "You live in the hearts of your parents and sister"]. 20 minutos (in Spanish). 12 April 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Vizoso, Sonia (30 December 2017). "La mujer de El Chicle niega ahora que estuviera con su marido la noche que desapareció Diana Quer". El País (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Encuentran el móvil de Diana Quer cerca del puerto de Taragoña" [Diana Quer's mobile found near port of Taragoña]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 27 October 2016. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Romero, Javier (1 January 2018). "El Chicle invitó a subir a su coche a tres chicas la noche antes del intento de rapto en Boiro" [El Chicle invited three girls into his car the night before the attempted kidnapping in Boiro]. La Voz de Galicia (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Águeda, Pedro; Precedo, José (31 December 2017). "El asesino de Diana Quer confiesa que la estranguló tras meterla en el coche la noche que desapareció" [Diana Quer's murderer confesses that he strangled her after taking her into his car on the night she disappeared]. El Diario (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- Romero, Javier (4 January 2019). "La vida en prisión de dos asesinos" [The prison life of two murderers]. La Voz de Asturias (in Spanish). Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- "Verdades, bulos y mucho morbo" [Truth, hoaxes and a lot of morbid fascination]. El Periódico de Aragón (in Spanish). 23 October 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- "Caso Diana: de la noticia al morbo" [Diana case: from news to morbid fascination]. El Correo Gallego (in Spanish). 5 September 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- "La hermana de Diana Quer estalla contra 'Espejo Público' por emitir una foto de su escote" [Diana Quer's sister explodes against 'Espejo Público' for broadcasting a photo of her cleavage]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). 30 October 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- García, Juan Manuel (9 September 2016). "Se busca mujer blanca, joven y de familia rica" [Looking for a young white woman from a rich family]. La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Rada, Juan (11 September 2016). "Desaparecida 'rica', desaparecida 'pobre': por qué se habla de Diana Quer y no de Manuela Chavero" [Missing 'rich woman', missing 'poor woman': why do we speak about Diana Quer and not about Manuela Chavero?]. El Español (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Martínez, A. (21 February 2017). "El padre de Iván Durán: "A mi hijo lo dejaron morir"" [Iván Durán's father: "They let my son die"]. La Voz de Galicia (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- Gómez, Concha (22 February 2017). "La autopsia indica que Iván Durán se suicidó al poco de dejar su casa" [Autopsy indicates that Iván Duran committed suicide shortly after leaving his house]. Atlántico (in Spanish). Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- "Una plaza y una escultura recuerdan a Diana Quer en Pozuelo, donde vivió" [Diana Quer remembered by square and sculpture in Pozuelo, where she lived]. ABC (in Spanish). 29 November 2018. Retrieved 4 January 2021.