Muqbil Al-Zahawi

Muqbil Al-Zahawi (born 1 April 1935) (Arabic, مقبل الزهاوى) is an Iraqi ceramicist. His creative and powerful sculptures and reliefs have been exhibited in museums, galleries, international shows, studios, and private residences throughout the U.S., Western Europe, and the Middle East. Al-Zahawi's works derive much inspiration from African Art, select Western artists, and his own background as an Iraqi Muslim.

Muqbil Al-Zahawi | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Born | 1 April 1935 |

| Education | University of Southern California University College London Central School of Art and Design |

| Style | Coiling, staining, reliefs, ceramic, sculpture |

| Website | zahawiart |

Al-Zahawi was born in Baghdad, Iraq, the son of an Iraqi lawyer from a prominent family of Kurdish origin, Dhafir Al-Zahawi, whose grand-uncle was the progressive Iraqi poet and scholar, Jamil Sidqi Al-Zahawi. As a budding artist, Al-Zahawi in the late 1950s began experimenting with a wide variety of artistic mediums eventually selecting ceramic sculptures constructed using the method of coiling. His forms have been described as "ancient", "whimsical", "sensual", "aggressive", and "powerful" all achieved through the textures, hollow spaces, earthy hues, and angular shapes that define this body of work.

Al-Zahawi lived most of his life outside of his native Iraq, residing in Geneva, Switzerland where he worked with the United Nations International Telecommunication Union. In his later years, he lived in Cairo, Egypt, and later in California. While war, sanctions, and civil strife thwarted his desire to eventually return to Iraq, he was able to portray his pride and love for his heritage through his art. Glyn Uzzell an artist and art teacher, as well as a long-time mentor of Al-Zahawi, once wrote: "It is clear that Zahawi has drawn strength and inspiration from a number of separate entities to forge a single style, uniquely his own."[1]

Early life

Muqbil Al-Zahawi was born in Baghdad, Iraq to Dhafir Al-Zahawi and Najia Baban, the last of seven children. His father was an Iraqi lawyer hailing from a long line of prominent Iraqis, which included bureaucrats, religious authorities (Mufti), poets, and scholars of Kurdish origin. He lived in Baghdad and attended the Jesuit's Baghdad College as well as the Institute of Fine Arts as an aspiring pianist. In 1950, at the age of 15 years old, Al-Zahawi moved to Cairo, Egypt with his mother. The popular uprising that overthrew King Farouk in 1952 and the eventual rise of the populist leader, Gamal Abdel-Nasser, instilled a sense of pride and patriotism in Al-Zahawi, which heavily influenced his life and his art. After moving to Santa Ana, California in 1952, he pursued different creative enterprises from drawing to fashion, music to acting, and eventually graduated with a B.A. in International Relations from the University of Southern California in 1957.

Beginnings as a ceramicist

.jpg.webp)

In 1958 Al-Zahawi moved to London to begin his post-graduate studies at the University College London in international relations. It was in London that Al-Zahawi decided to devote time to nurture his creative passions by simultaneously enrolling at London's Central School of Art and Design. At the Central School of Art, he began to devote his time to understanding terracotta ceramic sculptures, where he selected the coiling method. Through coiling, he felt he had complete control over the power evoked from his sculptures, which could not be achieved by the pinching method or throwing on a mechanical wheel.[2]

Al-Zahawi's early works took on more simplistic designs, extenuated by smoother lines, colorless texture (lacking stain), and relatively uniform spaces. This began to change when Al-Zahawi was introduced to primitive art, especially African Art through visits to the British Museum among other galleries and museums. Without a doubt African sculpture had a profound influence on his art thereafter. He would later travel and live in Africa (1965-1967) as a civil servant for the United Nations' mission in the Congo, only serving to reinforce his love and admiration of African art.

Switzerland

After completing his post-graduate diploma at University College London and studied at the Center School of Art, Al-Zahawi began Ph.D. studies at the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies. It is here that his art began to flourish and receive critical acclaim. His first one-man show took place at Galerie Club and Galerie Connaitre in 1962. During this time he also forged close bonds with the artists at Galerie Contemporaine in Carouge, Geneva including Glyn Uzzell, where he became one of the permanent artists from 1964–1982. Glyn Uzzell said, "when Muqbil Zahawi presented his first exhibition of ceramic sculpture in Geneva in 1962, it was immediately clear that one was in the presence of a highly original artist."[3]

After several years abroad, Al-Zahawi returned to Geneva in 1967 to begin working with the International Telecommunication Union. During this time, Al-Zahawi found fortune exhibiting all over Switzerland and Europe. He also began to experiment with new techniques including enlarging his sculptures and coloring his creations with his proprietary staining method. One of his most notable exhibitions of this period in the 1960s was a one-man show at the prestigious Musee Ariana in Geneva.[4] His work was well received and some of his pieces were later acquired by the Museum as part of their permanent collection.

In 1973 Al-Zahawi received a rare opportunity to undertake a one-man show in Neuchatel, Switzerland in the large exhibition halls of the Musee d’Art et d’Historie. What concerned him was the imbalance between the floor pieces and the abundance of bare wall space. He confided in Glyn Uzzell who suggested that Al-Zahawi try wall reliefs to complement his sculptures. Reliefs, as it turned out, was the perfect medium for his work given that this style of artistic display is historic in nature and therefore well-suited to Al-Zahawi's art that itself evokes an ancient and mysterious aura. He began to try his hands at various relief sizes, sketching each block, and masterfully bringing his sketches to life. Through this experiment, he was able to open up his work to a whole new audience that appreciated and actively acquired his wall mounted ceramic art.

The Neuchatel exhibition also pushed Al-Zahawi to test the bounds of physics by constructing much larger pieces. He endured a number of setbacks in the process where he created pieces that were too large to transport, bake (fire), and exhibit. After several attempts, he discovered that by creating the sculptures in two parts, one fitting inside the other for balance, he could build sculptures of the height and magnitude he hoped. The result: The Three Warriors, each over 6 feet tall, which became the centerpieces that anchored the Neuchatel exhibition.

Iraqi artists & Baghdad

.jpg.webp)

Iraqi artists have consistently been at the forefront of new and innovative works of creative genius in the Middle East.[5] From poets to scholars, sculptors to painters, the community of Iraqi artists, local and international, experimented with avant-garde and cutting-edge art, and found an insatiable audience that was often blind to gender, socioeconomic status, or identity. However, during the past 40 years, the art of Iraq and the voices of the artists has certainly paralleled the tumultuous political and social history of the country, creating an inextricable union that has been displayed in all forms of art.[6]

By the late 1970s Al-Zahawi's art was a true juxtaposition between the populist fervor of Pan-Arabism, the Decolonization of Africa, and rise of a new brand of nationalism, Ba'athism, in Iraq, contrasted with the influences of Western sculptors and painters including Henry Moore and Pablo Picasso. While Al-Zahawi had resided outside of the Middle East since 1952, he did have the opportunity to exhibit in Iraq in 1974 and again in 1977 at the behest of the Iraqi government.

His 1977 exhibit offered an opportunity for Al-Zahawi to reengage his roots through his art.[7] The exhibition showcased a number of unique pieces, and as a result of his hard work, the show was a resounding success, receiving patrons from all over Baghdad. Some of his pieces were eventually purchased for permanent acquisition by the Museum of Modern Art in Baghdad and National Gallery of Fine Arts in Amman, Jordan. Though this exhibition would be the last time Al-Zahawi would return to his native Iraq, given the political instability that beleaguered the nation, his love for Iraq remained steadfast and continued to be visible in his art thereafter.

Later years

Al-Zahawi ushered in the 1980s with style undertaking several successful exhibitions including one in Sion, Switzerland in 1980.[8] However, Al-Zahawi left Geneva in 1982 and took a prolonged hiatus that saw him exhibit only a handful of times in California and later Cairo, where he had relocated with his family.

In 1994 he had a received a fairly large commission for a collective show at the Riverside Art Museum in Riverside, California.[9] Of the exhibition, a critic said that "Among the dimensions that Zahawi's methods bring to his work are not only the clear signs of the artist's hands seen on every piece but include a generous measure of the artist's emotional attitudes in all their variety. You will find sculptures that speak of power and strength, of sensuality, of calligraphy and ancient knowledge, and of delightful bits of whimsy."[10]

Al-Zahawi undertook his last exhibition in 1998 at the age of 63 at Galerie de la Tour in Altkirch, France. With this one-man show, he brought to a close an illustrious career that spanned five decades. From 1958-1998 he exhibited in various countries across Europe, the Middle East, and the U.S. in countless galleries, museums, international shows, studios, and private residencies.

Influences

Al-Zahawi had several notable influences in the development of his art. Glyn Uzzell commented "Muqbil Zahawi was born in Baghdad, but has studied and lived in the United States for long periods. He has also lived and worked in Africa. Whether consciously acquired or unconsciously assimilated, the influences of these widely differing cultures are reflected in his art."[11] Indeed, African art dominated his early works and continued throughout his life. The powerful images of the art from the continent were especially powerful to Al-Zahawi, who saw them as direct, unequivocal, and uncompromising.

As he began to study and interact with the works of European artists, he infused their influences in his art. This was especially visible in Al-Zahawi's reliefs, which allowed him to create images that were influenced by his contemporaries, such as Henry Moore and Pablo Picasso who dominated the art scene throughout Al-Zahawi's active years.

Alongside these influences was his own background as an Iraqi and a Muslim. As a firm believer in Pan-Arabism and the zeitgeist of the 1960s and 1970s, his art began to reflect a sense of nationalism and historical significance. This related not only political sentiments but also religious narratives. It is "no coincidence that the climax of [his] body of work, with their tense and vibrant shapes, coincided with the effects of the volatile political landscape of his day."[12]

He once said, "Art should move people because of its total inner as well as outer form, not just by a work's decorative aspects. People do not need to fall in love with it, but it must elicit a strong emotional feeling," a feeling very much rooted in the political milieu of the time.[13]

The influences of his art not only dictated the shapes, colors, and designs, but also the display of his art with rougher textures, muted colors, and more edgy forms, all captured by his unique artistic methodology. One well known British art critic, Peter Fuller, commented, "The fantastic imagery of Eastern craftsmanship, with its perpetual insistence of a combination of fantastic, formal opulence and executive precision, synthesis with a proto-surrealist relish in suggestively aggressive symbol…they remain among the more powerful creations of his genre."[14]

Methodology

Through decades of experience, Al-Zahawi was able to formulate unique methods in crafting work that not only served to distinguish him as an artist but ensured his contribution to the field of ceramics through his novel approach in sketching, sculpting, and staining.

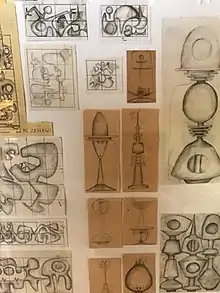

Sketching

Al-Zahawi began the process of his art through musings and pencil sketches. He notes that often these ideas come to him in his dreams, forcing him to wake up late at night to put the designs to paper so as to capture them in their most accurate and vivid form. Often these sketches, each unique in their own right, are combined and refined to eventually come to life through his art.

Coiling

Through the process of developing his art, Al-Zahawi tried various methods of sculpting, yet he vastly preferred the coiling method.[15] The coiling method allows the artists to create irregular forms with superimposed volume and with angles as sharp as 45°, collectively allowing for the construction of very large forms that can reach up to 7 feet high with a diameter as wide as 4 feet. As each inch is built, coil by coil, similar to how one builds a house, the final product becomes a one of a kind form that is rarely repeated, and oftentimes goes far beyond traditional ceramics.[16]

Reliefs

Reliefs are slightly more complicated than his sculptures. The pieces have to be completed as quickly as possible, sometimes within one day, so that they do not dry and contract in size. When a relief was finished, Al-Zahawi would cut the relief into equal-sized cross-sections that fit wooden squares (approximately 8 inches sq.) so as to allow each square to have its own design portion. Each square is then fired at 1000 °C (biscuit firing). Once firing is complete, each square is mounted back onto a large wooden surface to reconstruct the relief into its original design. Often the pieces do not align perfectly but this adds a more unique and creative element to the final finish.

Staining

As Glyn Uzzell noted, "Zahawi rejects the use of glazes, feeling that they can disguise the artist's intention with a superficially enhancing gloss. All of his works are stained in the natural colors of earth or atmosphere, and in a manner that shows the direct presence of the artist's hand."[17] Al-Zahawi overtime concocted his own recipe of wax, turpentine, and powder from various minerals to achieve the right composition to stain his sculptures and reliefs.

The stains or mineral powder (such as Hematite) are earth colors in various hues of brown, black, green, and blue. These colors are also accented by the original colors of the clay (red, white, or gray) to provide a further rich texture. After the stain is applied to the ceramic piece, Al-Zahawi would use a cloth with turpentine to remove some of the stain and reveal the texture of clay and patterns of the rib tool. The stain is then protected by a transparent wax that has limited shine but nevertheless allows the colors and shades of the stain and the rich texture to become more pronounced. Al-Zahawi has also experimented with engraving designs on the surface of certain sculptures to bring out a particular area or special form. With staining versus glazing, these engravings are extenuated and truly give the art a unique and exotic feel.

Personal

Al-Zahawi was married to Selma Al-Radi, a renowned Iraqi archaeologist and sister to famed Iraqi artist Nuha Al-Radi, and had a child from his first marriage, Rakan Al-Zahawi. Al-Zahawi later married Muazaz Amin Aziz, an Iraqi-Kurdish immigration lawyer, and had two children, Reem Al-Zahawi and Hamada Zahawi.

Exhibitions

Al-Zahawi exhibited in a wide number of forums throughout his 40 years as an active artist.

One-man shows

1962 - Galerie Club | Geneva, Switzerland

1962 - Galerie Connaitre | Geneva, Switzerland

1964, 1968, 1971, 1975, 1980 - Galerie Contemporaine | Geneva, Switzerland

1965 - Paul Rivas Gallery | Los Angeles, California (US)

1969 - Musee de l'Ariana | Geneva, Switzerland

1969 - Larsen Gallery | New York (US)

1971 - Ansdell Gallery | London, UK

1971 - Studio 5 | New York (US)

1973 - d’Art et d’Historie | Neuchatel, Switzerland

1976 - Galerie de le Cathedrale | Fribourg, Switzerland

1977, 1980 - Galerie Grand Fontaine | Sion, Switzerland

1977 - Museum of Modern Art | Baghdad, Iraq

1978 - Galerie Nydegg | Berne, Switzerland

1980 - Galeria Picpus | Montreux, Switzerland

1991 - Laguna Village | Laguna Beach, California (US)

1992, 1993 - Artist Studio | Cairo, Egypt

1994 - Riverside Art Museum | Riverside, California (US)

1998 - Galerie de la Tour | Altkirch, France

Collective Shows

1964, 1970, 1974 - Galerie Contemporaine | Geneva, Switzerland

1968, 1971 - Hotel Intercontinental] | Geneva, Switzerland

1969 - Salle Simon, I, Patino | Geneva, Switzerland

1972 - Musee Bellerive | Zurich, Switzerland

1974 - Galerie Maurice Colle & Cie | Geneva, Switzerland

1974 - Museum of Modern Art | Baghdad, Iraq

1976 - Biennale de Venise | Venice, Italy

1978 - Musee Rath | Geneva, Switzerland

1980 - Musee de l'Athenee | Geneva, Switzerland

1980 - Parc de la Mairie de Venier | Geneva, Switzerland

1981 - Palais d'Exposition (Artisites Suisses) | Delemont, Switzerland

1992 - Mandel Co. – Pacific Design Center | Los Angeles, California (US)

1992 - Mandel Co. Design Center | Laguna Niguel, California (US)

Permanent Collections

Musee Ariana | Geneva, Switzerland

Musee Bellerive | Zurich, Switzerland

Musee d’Art et d’Historie | Neuchatel, Switzerland

Museum of Modern Art | Baghdad, Iraq

International Telecommunication Union (UN) | Geneva, Switzerland

Galerie Contemporaine | Geneva, Switzerland

National Gallery of Fine Arts | Amman, Jordan

Reviews

Over the years Al-Zahawi's art has been reviewed by critics throughout the world. Here are a select few:

"He has a very fine sense of form and his work has an inner vitality that is the result of a clear concept, directly expressed. The exterior form of his work and the volume contained are interdependent. One feels that they are not simply shells, but a living space that has been caught and fixed by the outer wall. The forms, harmonious, sometimes, unexpected, but always well-conceive, are finely balanced."[18]

"…nous avons la non seulement la confirmation d'un admirable talent mais la revelation d'un art nouveau… Les ceramiques de Zahawi font songer a l'Antiquite orientale. Il y en ells un espirt de haute tradition. Parlant de l'art de Muqbil Zahawi, il faut ire art genial."[19]

"Il a cree par l'allusion du contour et de l'incision d'antiques divinites, des fontains muettes des minartes et des motifs de decoration archietecturale...la science du dessin fait reconnaitre in potier de grande classe."[20]

"Les sculptures du sculpteur-potier irakien Zahawi, aux forms organiques epurees jusqu'a la geometrie derniere, contribuent a mener le spectateur sur les hauts degres de la fascination. A voir absolument."[21]

See also

References

- Uzzell, Glyn. "About the Artist". Zahawi Art. Archived from the original on 1994. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Lakeside Pottery Tutorial. "Throwing a Pot". Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Uzzell, Glyn. "About the Artist (Abridged 1990)". Zahawi Art. Archived from the original on 1994. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Museum Ariana Brochure (1993)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1969. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Pocock, Charles. "Art in Iraq Today" (PDF). Retrieved 14 December 2016.

Recognized ceramicists include Muqbil Al-Zahawi

- Davis, Ben. "The Iraqi Century of Art". Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "1977 Baghdad Exhibition Catalogue". Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Zahawi: Sion Exhibition" (PDF). 13 Toiles, Reflets du Valais, No. 3 (March 1980). Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Riverside Art Museum Exhibition Catalogue (1994)". Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Cline, Mary. "Forward - Riverside Art Museum Exhibition Catalogue (1994)". Archived from the original on 1994. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Uzzell, Glyn. "About the Artist". Archived from the original on 1994. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Zahawi, Hamada. "Ode to my Father (2004)". Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Zahawi Art: News & Press". Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Peter, Fuller (September 21, 1971). "Review of Zahawi Exhibition at Ansdell Gallery". The Arts Review (London).

- "Making a Clay Coiled Pot". Lakeside Pottery Tutorial. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- "Zahawi Art: The Making of the Art". Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Uzzell, Glyn. "About the Artist". Zahawi Art. Archived from the original on 1994. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Uzzell, Glyn (December 7, 1962). "Around the Galleries" (Vol. 5, No. 49). Weekly Tribune.

- A.A.K (May 25–26, 1964). "Art Review". La Tribune de Geneve.

- Rainer, Michael Mason (October 15, 1969). "Art Review". La Tribune de Geneve.

- D.V. (December 10, 1976). "Art Review". La Tribune de Lausanne.