Mule spinners' cancer

Mule spinners' cancer or mule-spinners' cancer was a cancer, an epithelioma of the scrotum. It was first reported in 1887 in a cotton mule spinner.[1] In 1926, a British Home Office committee strongly favoured the view that this form of cancer was caused by the prolonged action of mineral oils on the skin of the scrotum, and of these oils, shale oil was deemed to be the most carcinogenic. From 1911 to 1938, there were 500 deaths amongst cotton mule-spinners from cancer of the scrotum, but only three amongst wool mule spinners.[2]

Introduction

About 1900, there was a high incidence of scrotal cancer detected in former mule spinners. The cancer was limited to cotton mule spinners and did not affect woollen or condenser mule spinners. The cause was attributed to the blend of vegetable and mineral oils used to lubricate the spindles. The spindles, when running, threw out a mist of oil at crotch height, that was captured by the clothing of anyone piecing an end. In the 1920s, much attention was given to this problem. Mules had used this mixture from the 1880s, and cotton mules ran faster and hotter than the other mules, and needed more frequent oiling. The solution was to make it a statutory requirement to only use vegetable oil or white mineral oils, which were believed to be non-carcinogens. But by then, cotton mules had been superseded by the ring frame and the industry was contracting, therefore it was never established if these measures were effective.[3]

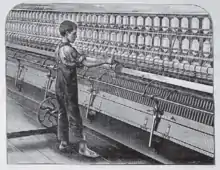

Mule spinning

A pair of 150-foot (46 m) long self-acting mules with 1320 spindles each would be tended by three employees: the minder or operative spinner, the big piecer, and the little piecer. The little piecer would start in the mulegate on his fourteenth birthday, and rise to the status of a minder. All these men worked barefoot, wearing white light cotton trousers. There were four basic tasks: creeling, doffing, cleaning and piecing.[4] Creeling and piecing would both be done while the mule was in motion. Creeling was about replacing the bobbins in the creel while piecing the old disappearing thread with the new; it was done from behind the mule. Piecing was about joining any ends that had broken. The piecer would catch the snarled fuzzy broken end at the top of the spindle in his right hand and pull out some clean thread and wrap it around the left forefinger. This would be pressed into clean roving emerging from the attenuating rollers, pulling the hand away when the two had twisted together. All this was done while walking back and forth with the carriage, contact being made using the three of four seconds when the piecer was close enough to lean over the frame and reach the rollers. At this moment, left arm and leg forward, his crotch was adjacent to the base of the spindles.[5]

The cancer

This cancer was a manifestation of scrotal squamous cell carcinoma which had first been noted in 1775 by Sir Percival Pott in climbing boys or chimney sweepers. It was the first industrially related cancer to be identified and was originally called soot wart, then chimney sweeps cancer. He describes it:

It is a disease which always makes it first attack on the inferior part of the scrotum where it produces a superficial, painful ragged ill-looking sore with hard rising edges ... in no great length of time it pervades the skin, dartos and the membranes of the scrotum, and seizes the testicle, which it inlarges [sic], hardens and renders truly and thoroughly distempered. Whence it makes its way up the spermatic process into the abdomen.

He comments on the life of the boys:

The fate of these people seems peculiarly hard ... they are treated with great brutality ... they are thrust up narrow and sometimes hot chimnies, [sic] where they are bruised burned and almost suffocated; and when they get to puberty they become ... liable to a most noisome, painful and fatal disease.

The carcinogen was thought to be coal tar possibly containing some arsenic.[6][7]

When the first case of scrotal squamous cell carcinoma in a cotton worker in the Manchester Hospital records in 1887, shale oil had been used in the mills for 35 years. A heavier oil was used once a day on the carriage and wheels but a lighter oil was applied three to four times to the spindles. The heavier oil may come into contact with the minders' hands, but it was the lighter oil that was sprayed from the spindles and saturated the spinners' light cotton trousers at the level of the pubis and groins above the scrotum. Piecers would remove any heavy oil from their hands by wiping them on the trousers. Brockbank in his 1941 paper:

In most men the bar is on a level with the pubis and groins above the scrotum. In a hot room the spinners in vest and overalls only perspire freely, and this must tend to wash off the natural grease on the skin and allow the oil to get onto it. In over 80% of the cases occur on the left side, this may be due to one or more of the following causes: firstly the left side hangs anatomically lower than the right, this will be more pronounced when the spinner is bending forward to piece with his left hand; perspiration from the lower part of the abdomen will then tend to run down the left side and the left side and less often the middle of the scrotum will come into contact with the left thigh and the oily trousers some hundreds of times a day.[1]

Mineral oil and alternative theories

Leitch reported, in 1922, that he had painted mineral oil from shale onto mice, inducing carcinomas, while Henry reported, in 1926, that shale oil was used on the rapidly rotating spindles, which, due to centrifugal force, sprayed out. There were, however, skeptics. Alternative theories included those such as the spinners were more susceptible to this cancer because they wore less clothing than wool spinners, and, notably, there was the issue of lack of underpants. Dr. Robertson argued the cancer was caused by stretching while piecing. In stretching, abrasion was caused by upward pull and consequent tightening of overalls dragging on the scrotum. Others blamed it on the want of bodily cleanliness.

Home Office enquiry

A Home Office enquiry was launched in March 1925 and reported back in 1926, with S. A. Henry of Manchester as secretary. It identified mineral oil as the prime cause and drew up a list of recommendations.

Recommendations

Firstly that guards should be fitted along the faller bar of all mules; and

- Institution of experimental research into oils with a view to finding oils which are innocuous and at the same time suitable as lubricants

- Development of a non-splash type of spindle bearing, more particularly for new mules

- Prevention of oil splash from the spindles of existing mules by means of some form of guard, the type to be decided by a series of tests to be mutually agreed upon and arranged by the Masters' Federation and the operative spinners

- Periodic medical examination of the workers

- (a) To be tried at first on a voluntary basis, but, if unsuccessful in one year or at any subsequent period, to be made compulsory

- (b) To be performed at the factory

- (c) To take place at least every four months

- (d) To include every worker in the mule-spinning room who is 30 years of age and over

- (e) To be performed by three or four medical men appointed by the trade, with Home Office approval, for the whole area or failing this by special medical men appointed for suitable areas by the Home Office in conjunction with trade representatives, all workers in any given area to be examined by one man.

- Education by periodic distribution of leaflets in order direct attention to the importance of cleanliness and to the dangers of delay in securing early treatment

See also

References

Notes

- Brockbank 1941

- Lee & McCann 1967, p. 148

- Catling 1986, p. 179

- Catling 1986, pp. 154, 160

- Catling 1986, p. 156

- Schwartz, Robert A. (2008). Skin Cancer: Recognition and Management (3 ed.). Wiley. p. 55. Retrieved 2011-05-02.

- Waldron 1983, p. 391

Bibliography

- Catling, Harold (1986). The Spinning Mule. Preston: The Lancashire Library. ISBN 0-902228-61-7.

- Lee, W. R.; McCann, J. K. (1967). "Mule Spinners' Cancer and the Wool Industry". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 24 (2): 148–51. doi:10.1136/oem.24.2.148. PMC 1008545. PMID 6071507.

- Brockbank, E. M. (1941). "Mule-Spinner's Cancer". BMJ. London. 1 (April 26th, 1941): 622–624. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4190.622. PMC 2161739. PMID 20783633.

- Waldron, H. A. (1983). "A brief history of scrotal cancer". British Journal of Industrial Medicine. 40 (4): 390–401. doi:10.1136/oem.40.4.390. PMC 1009212. PMID 6354246.