Moniliformis moniliformis

Moniliformis moniliformis is a parasite of the Acanthocephala phylum in the family Moniliformidae. The adult worms are usually found in intestines of rodents or carnivores such as cats and dogs. The species can also infest humans, though this is rare.

| Moniliformis moniliformis | |

|---|---|

| |

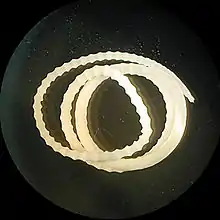

| Adult specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Acanthocephala |

| Class: | Archiacanthocephala |

| Order: | Moniliformida |

| Family: | Moniliformidae |

| Genus: | Moniliformis |

| Species: | M. moniliformis |

| Binomial name | |

| Moniliformis moniliformis (Bremser, 1811) | |

Distribution

Infested rats have been found world-wide. Cases of human infestation by Moniliformis moniliformis have been reported in the United States, Iran, Iraq, and Nigeria.[1]

Morphology

Acanthocephalans do not have digestive tracts and absorb nutrients through the tegument, the external layer. The scolex of this worm has a cylindrical proboscis and a multitude of curved hooks. The main parts of the worm body are the proboscis, neck, and trunk. Because of horizontal markings on the worm, there is the appearance of segmentation. Acanthocephalans are sexually dimorphic (dioecious) – adult males are generally 4 to 5 cm long while females are longer, ranging from lengths of 10 to 30 cm. Males also have copulatory bursas, used to hold on to the female during copulation and cement glands. Females have floating ovaries within a ligament sac where fertilization of the eggs occurs.[2] The eggs of this parasite are 90–125 μm long and 65 μm wide. They are oval in shape with a thick, clear outer coat.[3]

Reservoirs

Usually, the definitive hosts for M. moniliformis are rodents, cats, dogs and red foxes (in Poland); human infestations are rare. The intermediate hosts are usually beetles and cockroaches.[1][4]

Life cycle

In the life cycle of M. moniliformis, the intermediate hosts ingest the eggs of the parasite. In the intermediate host, the acanthor, or the parasite in its first larval stage, morphs into the acanthella, the second larval stage. After 6–12 weeks in this stage, the acanthella becomes a cystacanth. The cystacanth, or infective acanthella, of M. moniliformis are cyst-shaped and encyst in the tissues of the intermediate hosts. However, most other acanthocephalans have infective larvae that more closely resemble underdeveloped adult worms. The definitive hosts consume the cystacanths upon feeding on infested intermediate hosts. These cystacanths mature and mate in the small intestine in 8–12 weeks. After this time, the eggs are excreted with the feces, to be ingested yet again by another intermediate host and renew this cycle.[3]

The reproduction of the parasite only occurs in the definitive host. In acanthocephalans, adult males have cement glands in their posterior ends. The widely held theory is that the mucilaginous and proteinaceous substance that these glands secrete is used by males to seal up the females after copulation in order to prevent leakage of the inseminated sperm and further insemination by other males. It has also been found that these males may create this seal on other males in order to prevent them from copulating.[5] These seals, or copulatory caps, last for a week.

Behavioral changes in the intermediate host

In what is commonly known as "brain-jacking", the parasite induces a behavioral change in its intermediate host that increases the risk of predation for the host. It is thought that this behavioral change holds an evolutionary advantage for the parasite by increasing its chances of getting to its definitive host. When M. moniliformis infests its intermediate host, the cockroach species Periplaneta americana, it changes the cockroach's escape response. In one study, it was concluded that cockroaches infected by M. moniliformis took longer to respond to wind stimuli simulating the approach of a potential predator and displayed fewer escape responses implying that the parasite infection renders its intermediate host more vulnerable to predation by hindering its ability to detect and escape from its predator. It is thought that serotonin plays a role in upending the communication between giant interneurons and the thoracic interneurons and in turn hampers the escape response of the cockroach.[6] In a similar study, the effects of parasitism on three Periplaneta species are studied. The results show that Periplaneta australasiae uses substrates differently and moves around less when infected with Moniliformis moniliformis.[7] Another study concludes an increased vulnerability of infected Periplaneta americana due to increased phototaxis, more time spent moving (due to slower movement) and movement in response to light (uninfected cockroaches hesitated before moving).[8]

Human infection

As it requires consumption of raw infested beetles or cockroaches, human acanthocephaliasis is rare.

Clinical manifestations

In 1888 in Italy, Salvatore Calandruccio infected himself by ingesting larvae, reported gastrointestinal disturbances, and then shed the eggs in two weeks. This was the first report of the clinical manifestations of an M. moniliformis infestation in humans.

Calandruccio provided the first description of the clinical manifestations of acanthocephaliasis and similar accounts are found in the few case studies since; many of the patients described were asymptomatic. When they showed symptoms, they normally experienced abdominal pain, diarrhea, dizziness, edema, and anorexia.[9] In some patients, giddiness has also been reported.[1] In rodents, acanthocephaliasis is fatal and manifests itself through hemorrhaging and gastrointestinal disturbance.

Diagnosis

The proper diagnosis of acanthocephaliasis in humans is made through fecal analysis, which, if the host is infested, should contain adult worms or eggs. To obtain the worms from the host, piperazine citrate, levamisole and bithionol can be administered to the patient.[9]

Treatment

Acanthocephaliasis is treated with anti-helminthics. There is considerable debate over the efficacy of anti-helminth drugs on this parasite but, so far, the drugs seem to be working. Pyrantel pamoate and ivermectin have been shown to be particularly effective in treating patients.[9] Mebendazole and thiabendazole have also both been cited to work.[6][10]

Prevention strategies

Because the only way of developing acanthocephaliasis is through ingesting the intermediate hosts, the most effective means of prevention is avoiding the consumption of uncooked beetles and cockroaches. This is especially difficult in children exhibiting pica and in areas with poor hygiene. Awareness campaigns on the risks of consuming infested beetles and cockroaches would be effective. Moreover, preventing entry of the intermediate hosts into the home, and especially the kitchen where it is at risk of getting into the food, would help curb the risk of becoming infested.[11]

References

- , "Acanthocephalan Worms." Gideon. Gideon Informatics. Web.

- , "Phylum: Acanthocephala." Lecture. Animal Parasitology. Kansas State, 14 March 2005. Web. 23 February 2010.

- , Acanthocephaliasis. Parasites and Health. CDC, 20 July 2009. Web.

- Crompton, D.W.T. Reproduction. In Biology of the Acanthocephala (ed. Crompton, D. W. T. & Nickol, B. B.), pp. 213–271. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 1985

- Berenji, F; Fata, A; Hosseininejad, Z (2007). "A case of Moniliformis moniliformis (Acanthocephala) infection in Iran". Korean J Parasitol. 45: 145–8. doi:10.3347/kjp.2007.45.2.145. PMC 2526305. PMID 17570979.

- Moore, J.; Freehling, M.; Gotelli, N. J. (1994). "Altered behavior in two species of blattid cockroaches infected with Moniliformis moniliformis (Acanthocephala)". Journal of Parasitology. 80: 220–223. doi:10.2307/3283750. JSTOR 3283750.

- Moore, J (1983). "Altered behaviour in cockroaches (Periplaneta americana) infected with an archiacantho- cephalan Moniliformis moniliformis" (PDF). J. Parasitol. 69: 1174–1177. doi:10.2307/3280893. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011.

- Richardson, Dennis J.; Krause, Peter J. (2003). North American Parasitic Zoonoses. Volume 6. Boston: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-7212-3.

- Salehabadi, Alireza (2008). "Human Infection with Moniliformis moniliformis (Bremser 1811) (Travassos 1915) in Iran: Another Case Report After Three Decades". Vector-Borne and Zoonotic Diseases. 8: 101–104. doi:10.1089/vbz.2007.0150. PMID 18237263.

- Neafie, RC; Marty, AM (1993). "Unusual infections in humans". Clin Microbiol Rev. 66: 34–56. PMC 358265.