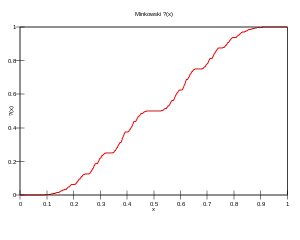

Minkowski's question-mark function

In mathematics, the Minkowski question-mark function denoted by ?(x), is a function possessing various unusual fractal properties, defined by Hermann Minkowski (1904, pages 171–172). It maps quadratic irrationals to rational numbers on the unit interval, via an expression relating the continued fraction expansions of the quadratics to the binary expansions of the rationals, given by Arnaud Denjoy in 1938. In addition, it maps rational numbers to dyadic rationals, as can be seen by a recursive definition closely related to the Stern–Brocot tree.

Definition

If [a0; a1, a2, …] is the continued-fraction representation of an irrational number x, then

whereas if [a0; a1, a2, …, am] is a continued-fraction representation of a rational number x, then

Intuitive explanation

To get some intuition for the definition above, consider the different ways of interpreting an infinite string of bits beginning with 0 as a real number in [0, 1]. One obvious way to interpret such a string is to place a binary point after the first 0 and read the string as a binary expansion: thus, for instance, the string 001001001001001001001001... represents the binary number 0.010010010010..., or 2/7. Another interpretation views a string as the continued fraction [0; a1, a2, …], where the integers ai are the run lengths in a run-length encoding of the string. The same example string 001001001001001001001001... then corresponds to [0; 2, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, …] = √3 − 1/2. If the string ends in an infinitely long run of the same bit, we ignore it and terminate the representation; this is suggested by the formal "identity":

- [0; a1, …, an, ∞] = [0; a1, …, an + 1/∞] = [0; a1, …, an + 0] = [0; a1, …, an].

The effect of the question-mark function on [0, 1] can then be understood as mapping the second interpretation of a string to the first interpretation of the same string,[1][2] just as the Cantor function can be understood as mapping a triadic base-3 representation to a base-2 representation. Our example string gives the equality

Recursive definition for rational arguments

For rational numbers in the unit interval, the function may also be defined recursively; if p/q and r/s are reduced fractions such that |ps − rq| = 1 (so that they are adjacent elements of a row of the Farey sequence) then[3][2]

Using the base cases

it is then possible to compute ?(x) for any rational x, starting with the Farey sequence of order 2, then 3, etc.

If pn−1/qn−1 and pn/qn are two successive convergents of a continued fraction, then the matrix

has determinant ±1. Such a matrix is an element of SL(2, Z), the group of 2 × 2 matrices with determinant ±1. This group is related to the modular group.

Self-symmetry

The question mark is clearly visually self-similar. A monoid of self-similarities may be generated by two operators S and R acting on the unit square and defined as follows:

Visually, S shrinks the unit square to its bottom-left quarter, while R performs a point reflection through its center.

A point on the graph of ? has coordinates (x, ?(x)) for some x in the unit interval. Such a point is transformed by S and R into another point of the graph, because ? satisfies the following identities for all x ∈ [0, 1]:

These two operators may be repeatedly combined, forming a monoid. A general element of the monoid is then

for positive integers a1, a2, a3, …. Each such element describes a self-similarity of the question-mark function. This monoid is sometimes called the period-doubling monoid, and all period-doubling fractal curves have a self-symmetry described by it (the de Rham curve, of which the question mark is a special case, is a category of such curves). The elements of the monoid are in correspondence with the rationals, by means of the identification of a1, a2, a3, … with the continued fraction [0; a1, a2, a3,…]. Since both

and

are linear fractional transformations with integer coefficients, the monoid may be regarded as a subset of the modular group PSL(2, Z).

Quadratic irrationals

The question mark function provides a one-to-one mapping from the non-dyadic rationals to the quadratic irrationals, thus allowing an explicit proof of countability of the latter. These can, in fact, be understood to correspond to the periodic orbits for the dyadic transformation. This can be explicitly demonstrated in just a few steps.

Dyadic symmetry

Define two moves: a left move and a right move, valid on the unit interval as

- and

and

- and

The question mark function then obeys a left-move symmetry

and a right-move symmetry

where denotes function composition. These can be arbitrary concatenated. Consider, for example, the sequence of left-right moves Adding the subscripts C and D, and, for clarity, dropping the composition operator in all but a few places, one has:

Arbitrary finite-length strings in the letters L and R correspond to the dyadic rationals, in that every dyadic rational can be written as both for integer n and m and as finite length of bits with Thus, every dyadic rational is in one-to-one correspondence with some self-symmetry of the question mark function.

Some notational rearrangements can make the above slightly easier to express. Let and stand for L and R. Function composition extends this to a monoid, in that one can write and generally, for some binary strings of digits A, B, where AB is just the ordinary concatenation of such strings. The dyadic monoid M is then the monoid of all such finite-length left-right moves. Writing as a general element of the monoid, there is a corresponding self-symmetry of the question mark function:

Isomorphism

An explicit mapping between the rationals and the dyadic rationals can be obtained providing a reflection operator

and noting that both

- and

Since is the identity, an arbitrary string of left-right moves can be re-written as a string of left moves only, followed by a reflection, followed by more left moves, a reflection, and so on, that is, as which is clearly isomorphic to from above. Evaluating some explicit sequence of at the function argument gives a dyadic rational; explicitly, it is equal to where each is a binary bit, zero corresponding to a left move and one corresponding to a right move. The equivalent sequence of moves, evaluated at gives a rational number It is explicitly the one provided by the continued fraction keeping in mind that it is a rational because the sequence was of finite length. This establishes a one-to-one correspondence between the dyadic rationals and the rationals.

Periodic orbits of the dyadic transform

Consider now the periodic orbits of the dyadic transformation. These correspond to bit-sequences consisting of a finite initial "chaotic" sequence of bits , followed by a repeating string of length . Such repeating strings correspond to a rational number. This is easily made explicit. Write

one then clearly has

Tacking on the initial non-repeating sequence, one clearly has a rational number. In fact, every rational number can be expressed in this way: an initial "random" sequence, followed by a cycling repeat. That is, the periodic orbits of the map are in one-to-one correspondence with the rationals.

Periodic orbits as continued fractions

Such periodic orbits have an equivalent periodic continued fraction, per the isomorphism established above. There is an initial "chaotic" orbit, of some finite length, followed by the a repeating sequence. The repeating sequence generates a periodic continued fraction satisfying This continued fraction has the form[3]

with the being integers, and satisfying Explicit values can be obtained by writing

for the shift, so that

while the reflection is given by

so that . Both of these matrices are unimodular, arbitrary products remain unimodular, and result in a matrix of the form

giving the precise value of the continued fraction. As all of the matrix entries are integers, this matrix belongs to the projective modular group

Solving explicitly, one has that It is not hard to verify that the solutions to this meet the definition of quadratic irrationals. In fact, every quadratic irrational can be expressed in this way. Thus the quadratic irrationals are in one-to-one correspondence with the periodic orbits of the dyadic transform, which are in one-to-one correspondence with the (non-dyadic) rationals, which are in one-to-one correspondence with the dyadic rationals. The question mark function provides the correspondence in each case.

Properties of ?(x)

The question-mark function is a strictly increasing and continuous,[4] but not absolutely continuous function. The derivative vanishes on the rational numbers. There are several constructions for a measure that, when integrated, yields the question-mark function. One such construction is obtained by measuring the density of the Farey numbers on the real number line. The question-mark measure is the prototypical example of what are sometimes referred to as multi-fractal measures.

The question-mark function maps rational numbers to dyadic rational numbers, meaning those whose base two representation terminates, as may be proven by induction from the recursive construction outlined above. It maps quadratic irrationals to non-dyadic rational numbers. It is an odd function, and satisfies the functional equation ?(x + 1) = ?(x) + 1; consequently x → ?(x) − x is an odd periodic function with period one. If ?(x) is irrational, then x is either algebraic of degree greater than two, or transcendental.

The question-mark function has fixed points at 0, 1/2 and 1, and at least two more, symmetric about the midpoint. One is approximately 0.42037.[4] It was conjectured by Moshchevitin that they were the only 5 fixed points.[5]

In 1943, Raphaël Salem raised the question of whether the Fourier–Stieltjes coefficients of the question-mark function vanish at infinity.[6] In other words, he wanted to know whether or not

This was answered affirmatively by Jordan and Sahlsten,[7] as a special case of a result on Gibbs measures.

The graph of Minkowski question mark function is a special case of fractal curves known as de Rham curves.

Algorithm

The recursive definition naturally lends itself to an algorithm for computing the function to any desired degree of accuracy for any real number, as the following C function demonstrates. The algorithm descends the Stern–Brocot tree in search of the input x, and sums the terms of the binary expansion of y = ?(x) on the way. As long as the loop invariant qr − ps = 1 remains satisfied there is no need to reduce the fraction m/n = p + r/q + s, since it is already in lowest terms. Another invariant is p/q ≤ x < r/s. The for loop in this program may be analyzed somewhat like a while loop, with the conditional break statements in the first three lines making out the condition. The only statements in the loop that can possibly affect the invariants are in the last two lines, and these can be shown to preserve the truth of both invariants as long as the first three lines have executed successfully without breaking out of the loop. A third invariant for the body of the loop (up to floating point precision) is y ≤ ?(x) < y + d, but since d is halved at the beginning of the loop before any conditions are tested, our conclusion is only that y ≤ ?(x) < y + 2d at the termination of the loop.

To prove termination, it is sufficient to note that the sum q + s increases by at least 1 with every iteration of the loop, and that the loop will terminate when this sum is too large to be represented in the primitive C data type long. However, in practice, the conditional break when y + d == y is what ensures the termination of the loop in a reasonable amount of time.

/* Minkowski's question-mark function */

double minkowski(double x) {

long p = x;

if ((double)p > x) --p; /* p=floor(x) */

long q = 1, r = p + 1, s = 1, m, n;

double d = 1, y = p;

if (x < (double)p || (p < 0) ^ (r <= 0))

return x; /* out of range ?(x) =~ x */

for (;;) { /* invariants: q * r - p * s == 1 && (double)p / q <= x && x < (double)r / s */

d /= 2;

if (y + d == y)

break; /* reached max possible precision */

m = p + r;

if ((m < 0) ^ (p < 0))

break; /* sum overflowed */

n = q + s;

if (n < 0)

break; /* sum overflowed */

if (x < (double)m / n) {

r = m;

s = n;

} else {

y += d;

p = m;

q = n;

}

}

return y + d; /* final round-off */

}

See also

Notes

- Finch (2003) pp. 441–442.

- Pytheas Fogg (2002) p. 95.

- Khinchin, A. Ya. (1964) [Originally published in Russian, 1935]. Continued Fractions. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-486-69630-8. This is now available as a reprint from Dover Publications.

- Finch (2003) p. 442

- Nikolay Moshchevitin, open problems session, Diophantine Problems, Determinism and Randomness, at CIRM, 25 November 2020

- Salem (1943)

- Jordan and Sahlsten (2013)

Historical references

- Minkowski, Hermann (1904), "Zur Geometrie der Zahlen", Verhandlungen des III. internationalen Mathematiker-Kongresses in Heidelberg, Berlin, pp. 164–173, JFM 36.0281.01, archived from the original on 4 January 2015

- Denjoy, Arnaud (1938), "Sur une fonction réelle de Minkowski", J. Math. Pures Appl., Série IX (in French), 17: 105–151, Zbl 0018.34602

References

- Alkauskas, Giedrius (2008), Integral transforms of the Minkowski question mark function, PhD thesis, University of Nottingham.

- Bibiloni, L.; Paradis, J.; Viader, P. (1998), "A new light on Minkowski's ?(x) function", Journal of Number Theory, 73 (2): 212–227, doi:10.1006/jnth.1998.2294, hdl:10230/843, Zbl 0928.11006, archived from the original on 22 June 2015.

- Bibiloni, L.; Paradis, J.; Viader, P. (2001), "The derivative of Minkowski's singular function", Journal of Mathematical Analysis and Applications, 253 (1): 107–125, doi:10.1006/jmaa.2000.7064, Zbl 0995.26005, archived from the original on 22 June 2015.

- Conley, R. M. (2003), A Survey of the Minkowski ?(x) Function, Masters thesis, West Virginia University.

- Conway, J. H. (2000), "Contorted fractions", On Numbers and Games (2nd ed.), Wellesley, MA: A K Peters, pp. 82–86.

- Finch, Steven R. (2003), Mathematical constants, Encyclopedia of Mathematics and Its Applications, 94, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-81805-6, Zbl 1054.00001

- Jordan, Thomas; Sahlsten, Tuomas (2016), "Fourier transforms of Gibbs measures for the Gauss map", Mathematische Annalen, 364 (3–4): 983–1023, arXiv:1312.3619, Bibcode:2013arXiv1312.3619J, doi:10.1007/s00208-015-1241-9

- Pytheas Fogg, N. (2002), Berthé, Valérie; Ferenczi, Sébastien; Mauduit, Christian; Siegel, A. (eds.), Substitutions in dynamics, arithmetics and combinatorics, Lecture Notes in Mathematics, 1794, Berlin: Springer-Verlag, ISBN 978-3-540-44141-0, Zbl 1014.11015

- Salem, Raphaël (1943), "On some singular monotonic functions which are strictly increasing" (PDF), Transactions of the American Mathematical Society, 53 (3): 427–439, doi:10.2307/1990210, JSTOR 1990210

- Vepstas, L. (2004), The Minkowski Question Mark and the Modular Group SL(2,Z) (PDF)

- Vepstas, L. (2008), "On the Minkowski Measure", arXiv:0810.1265 [math.DS]