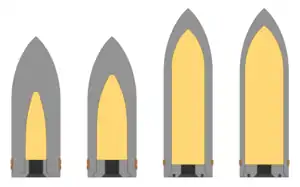

Mine shell

A mine shell is a military shell type characterized by thin shell walls and a correspondingly high payload of explosives. The shell type was originally developed during the mid 1800's against non reinforced fortresses but got a new role post WW2 against air targets as reinforced fortresses had made the original use of the type became common around the turn of the century (1899-1900).

Armor piercing high explosive shell.

Semi armor piercing high explosive shell.

High explosive shell.

Mine shell.

In English the term is often a direct translation of the German term Minengeschoss (German: Minengeschoß).

Effect, construction and use

The mine shell is a more explosive version of the common high-explosive and high-explosive fragmentation shells, relying on inflicting damage primarily through the blast rather than via the combination of penetration, blast and fragmentation achieved by normal ammunition. This is referred to in Swedish as tryckvågsverkan, meaning pressure wave damage.[1] This effect is desirable when attacking materials such as concrete or aircraft skin that are relatively easy to penetrate and therefore do not need to be tackled with heavy, hard projectiles, but are tough enough to maintain their structure despite being pierced by shellfire. The larger explosions generated by mine shells are more efficient at inflicting damage on such targets than the greater kinetic impact but smaller detonations delivered by conventional rounds. To achieve this effect mine shells feature very thin shell walls and thus more room for explosive filler; though at the cost of generating lighter and thus somewhat less formidable shrapnel.[2][1]

An additional advantage of this approach is that, explosives being lighter than metal, the projectiles weigh less, which gives them higher muzzle velocity compared to heavier shells. For the same reason, they also generate less recoil. However less desirably, the reduced mass inevitably entails that they will possess less momentum, which reduces their range. It is also a consideration that the lower recoil makes them unsuitable to be fired from the same gun as standard shells of comparable power, if it uses a recoil operated or advanced primer ignition mechanism.

Name

The word 'mine' in the name mine shell, although in English its directly translated from the German word minengeschoß, does not refer to the modern use of the word, for example land mine and naval mine. Mine is an old (but still used) munition term from, among others, the weapons terminologies of Germany and Sweden.[2][1] While the munition term "mine" in its original languages (German: Mine, Swedish: min) differs from their respective words for land mines (German: Landmine, (or just) Mine, Swedish: mina) the munition term originates from the original meaning of the word mine which originally meant something along the lines of explosive ordnance, unlike the modern meaning of the word which is more defined.

The munition term itself (German: Minenwirkung, Swedish: minverkan), which roughly translates to "mine power" or "mine effect", specifically means an explosive device, mainly a projectile, that damages its intended target with the power of the pressure wave created from the explosion.

History

Dedicated mine shells originate in Germanic countries such as Germany and Sweden with the earliest known type being for a Swedish 22 cm naval howitzer from 1878;[3] although it's very possible the type was used previous to this as the German and Swedish terminology system has its roots from the 18th century. The shell type was used in a lot of different types of high caliber cannons both on land and on water around the turn of the century before seeing a decline around World War I.[4] It was probably decided that mine shells had a smaller field of use on the modern battlefield compared to the fairly similar high-explosive shell.

German use of mine shells in World War II

During World War II, mine shells would see a resurgence as the Germans started to use the type in small caliber (initially 15-20 mm) automatic weapons, both to arm the Luftwaffe's fighter aircraft and for Flak. This was an innovation, as prior to this, mine shells had only been constructed in large calibers for technical reasons. Larger shells were usually produced by casting, smaller calibers by drilling the cavity for fuse and explosives into a solid steel shot, and neither process was effective at making small projectiles with walls that were sufficiently thin yet strong enough to work as a mine shell. While small thick-walled shells fired from automatic guns performed well against ground targets, they were more limited in anti-aircraft use.

In the late 1930s, the Germans began to pay attention to these shortcomings during the trials of the 20 mm MG FF cannon.[5] Its conventional high explosive rounds were judged unsatisfactory in the anti-aircraft role, for the reasons mentioned above. As a result of these trials, the German ministry of air defense "Reichsluftministerium", or "RLM" for short, ordered the development of mine shells for the 20 mm MG FF cannon in 1937.[5] To make such shells in 20 mm caliber, German ordnance engineers had to try new methods of construction; what they came up with was a round made from high quality drawing steel, manufactured in the same way in which cartridge cases are made. [6] These new 20 mm mine shells were first used against the RAF in 1940, and proved highly successful. Even when the British and later, to a limited extent the Americans equipped their fighters with autocannon, they always used conventional ammunition. The difference in payloads between these rounds and the Luftwaffe's mine shells was significant. Considering the high explosive rounds alone as an example: the 20 mm mine shells used in MG-FF/M cannons (and later in the MG 151/20) both had a 17 gm HE filling while British and American WW II autocannon shells of the same calibre, but markedly heavier could carry only 10-12 gm; while the typical filler load in the conventional 20 mm shells of the original MG-FF was a mere 4.5 to 6.5 gm.

As mentioned above, one problem with the new ammunition was that due to their lightweight nature, the new 20 mm mine shells produced insufficient recoil to operate the 20 mm MG FF cannon. This required a modification of the recoil mechanism so the cannon could fire this new shell, but this in turn made it unsafe to fire the old, conventional rounds. In an effort to avoid the chambering of incorrect ammunition, the modified weapon was redesignated the 20 mm MG FF/M, M for Minengeschoß.

Germany first used Minengeschoß ammunition during the Battle of Britain when MG FF/M armed Bf 109E's and Bf 110C's flew missions over from mainland Europe to Britain. Although the shells themselves proved deadly, the guns had a poor rate of fire, relatively sluggish muzzle velocity and an inadequate magazine ammunition feed, and were soon to be replaced by the belt-fed MG 151. This new type was originally introduced as a Minengeschoß-firing heavy machine gun, in 15 mm; but then it was realised that the earlier cannon-sized Mine shells were more effective, and so a new larger cartridge (20x82mm) was created for the weapon. The adapted gun, (more precisely designated the MG 151/20), became the Luftwaffe's standard 20 mm autocannon until the end of the war,[7] and with its high fire rate coupled with good ballistics and high explosives payload for its caliber was overall among the best aircraft armament of the conflict.[8][9]

As the possibilities of this new application for mine shells became better understood, the Luftwaffe found they had created a potential game changer as the recoil/velocity ratio made it possible to create larger caliber guns that would have low enough recoil to be effectively mounted on conventional aircraft, while at the same time achieving useful velocities. Moreover, as the volume of a cylinder is proportional to the square of its radius, and as cannon shells tend to the shape of a cylinder, the Minengeschoß design when applied to larger calibers allowed a dramatic increase in explosive payload and power. One such weapon was the 30 mm MK 108 which became highly militarily significant during the second half of the war, when the Allies began to mount their enormous bombing onslaught on German cities. So large was the increase in internal volume indeed that it proved worthwhile to the Germans to refine these projectiles by making them more streamlined, sacrificing a little of this capacity, but thus partly compensating for the lower momentum characteristic of the Minengeschoß design. These streamlined mine shells for the 30 mm MK 108 were designated Ausf.C.[10] and featured 72 grams of nitropenta (PETN), compared to the original blunt-nosed Ausf.A which had 85 grams of PETN. (Note that the Ausf.B was a training shell without explosives.) See below for a comparison with modern ammunition loads.

Mine shells where also adopted for use in ground attack cannons like the high-velocity 30 mm MK 103, among others,[11][12] as well as anti-aircraft guns like the 20 mm and 37 mm FLAK guns.

Post-war use

After the defeat of Germany in World War II, several countries started using mine shells for their own post-war aircraft and anti-aircraft armament, for example in the HE shells of Britain's ADEN cannon and the French DEFA 540. The guns themselves were developments of the German Mauser MG 213.

Even in comparison to modern designs, some of the WW2 payloads quoted above are impressive as not even the PGU-13/B HEI round for the GAU-8/A Avenger gun of the A-10 Warthog or the 30 mm OFZ shell of Russian GSh-301 and GSh-30-6 cannons come close to the German WW2 mine shells of the same caliber - 72-85 grams compared to 58 to 48,5 grams respectively for the PGU-13B and OFZ.

Sweden having experience with the shell type from earlier developed several different mine shells in several different calibers after the war. Some examples being a mine shell variant for the 20 x 110 Hispano cartridge[13] and one for the 57 x 230R Bofors cartridge.[14]

The type is still used today in autocannons such as the Mauser BK-27[15] but there is no known use of the type as it was originally used.

References

Citations

- Lärobok i Militärteknik, vol. 4: Verkan och skydd.

- Nordisk familjebok.

- "22 cm mingranat för haubits fm/78".

- The type can be found in Swedish ammunition manuals for guns in caliber 75-150 mm around the years 1902-1914 disappearing from manuals after WW1 to the start of WW2.

- "Shell types: Minengeschoß".

- http://quarryhs.co.uk/ideal.htm

- Williams and Gustin 2003

- http://www.quarryhs.co.uk/CannonMGs.htm

- /http://www.quarryhs.co.uk/WW2guneffect.htm

- http://www.quarryhs.co.uk/ideal.htm

- Forsyth 1996, p. 168

- Note: The information in Forsyth 1996 is on the design and construction of the MK 108 and the relevant Minengeschoss.

- Beskrivning över 20 mm AKAN m/49. Stockholm: KFF förlag. 1955. Sweden. 1955.

- Flyghistorisk revy nummer 31, SAAB 18. Sweden: The Swedish air historical society. 1984. p. 76.

- "Gripens vapen (the weapons of the Griffon) pdf" (PDF).