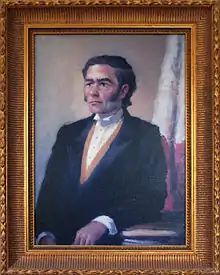

Mikiel Anton Vassalli

Mikiel Anton Vassalli (March 5, 1764 in Żebbuġ, Malta – January 12, 1829) was a Maltese writer, a philosopher, and a linguist who published important Maltese language books, including a Maltese-Italian dictionary, a Maltese grammar book, the first Protestant Gospels in Maltese, and towards the end of his life, a book on Maltese proverbs.[1]

Mikiel Anton Vassalli | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Mikiel Anton Vassalli 5 March 1764 Żebbuġ, Malta |

| Died | January 12, 1829 Malta |

| Occupation | lexicographer, writer, freedom fighter |

| Nationality | Maltese |

Life

Mikiel Anton Vassalli was born in Ħaz-Żebbuġ in 1764 to a peasant family, and lost his father at the age of two. In 1785, at the age of 21, he started studies of oriental languages in the Sapienza University of Rome.

He died in 1829 and, having been refused burial by the Catholic Church. Vassalli was buried in the Msida Bastions Garden of Rest, a Protestant cemetery mainly used by the British.[2]

Maltese Language

Maltese grammars and dictionaries had already been written before the century, but all of them have long since been lost. It is for this reason that the honour of being the author of the first grammar goes to Canon Giovanni Pietro Francesco Agius de Soldanis for his Della lingua púnica presentemente usata da Maltesi in Roma (1750).[3] It was only in the 1790s that Vassalli, alone among Maltese nationalists, took an interest in purifying the language of Italianisms and reviving it as a national language.

During the nineties Vassalli published three substantial works about the Maltese language, which set the study of the Maltese language for the first time on solid and scientific foundations. These works were:

- L-Alfabett Malti (1790), Lill-Malti li qiegħed jaqra

- Ktieb il-Kliem Malti (1796) - a Maltese-Latin-Italian dictionary.

- il-Mylsen (1791) - a Maltese grammar in Latin.

The introduction to the dictionary has a strong social and political flavour which makes it very clear that Vassalli's primary aim was not the Maltese language in itself, but the civil and moral education of the Maltese people which he believed could only be attained through their native language. One can easily point out Vassalli's Discorso Preliminare as second only to the Constitution of the Republic in that it is a beautiful and precious document for the Maltese Nation to whom it was dedicated with the words: "Alla Nazione Maltese", a phrase which in those days could only be the fruits of a very fertile imagination.

With the help of John Hookham Frere, Vassalli began to teach at the University of Malta as the first Professor of the Maltese language, and produced other works:

- a new Maltese grammar in Italian (1827)

- a book of Maltese Proverbs (1828),

- a translation of the Gospels.[4]

Vassalli's call was above everything else a political one favouring the education of the Maltese masses and the development of Maltese potential in all possible areas and the accessibility to the realms of wisdom and law so that the Maltese nation could arrive at a full consciousness of itself, its duties and identify itself as a nation in its own right. This is therefore a movement in favour of democratic power. The Maltese language was to be the primary instrument for this process.

Vassalli was the first to study Maltese scientifically and according to its Semitic roots. He proposed it as an alternative to foreign languages which up to that time had always been employed in all areas involving intellect and culture. Thus for the first time the Maltese language appeared as an instrument for popular education and made a claim for power. It was inevitable that Vassalli's revolutionary call would have many obstacles to overcome in the process of its realization.

Politics

Mikiel Anton Vassalli was expelled from Malta a number of times during his life due to his political beliefs. He lived during one of the most turbulent periods of Maltese history: the final years of the Knights of St. John, the two years of Napoleonic government (1798–1800), and the first years of British rule from 1800. For a time he was suspected to have been the author of the Francophile publication, Recherches Historiques et Politiques sur Malte (Paris, 1798), however, this was later attributed to the Maltese lawyer, Onorato Bres.[5] Besides the social disorder that was an outcome of political upheaval, there was also a deeply felt division between the social classes: the privileged class on one hand and on the other the vast majority.

It was a time of great turmoil when Europe was beset with revolutionary ideas which would come to a head with the French Revolution having as its ideals liberty and power to the people. As any other active and intelligent youth would, Vassalli closely followed all the developments that were taking place and absorbed the social ideas, besides doing very well in his academic studies.

After studies in Italy Vassalli returned to Malta and to a new phase of political involvement. We can picture this young man bursting with revolutionary ideas, returning to Malta and witnessing the disorder of the final years of the Order of St. John, overwhelmed by financial problems, by divisions running deeply within it and, worst of all, by the backwardness. Shocked by the precarious situation Malta was to be found in, and particularly his fellow Maltese, Vassalli listed some suggestions for the Grandmaster of the Order. Amongst other things he asked:

- That the Order would stop all fighting with the Moslems, an activity which was out of step with the times

- That Maltese harbours would be open for commerce with all countries

- That the Order would introduce a branch for Maltese wishing to become knights.

These suggestions were aimed at improving the financial condition of the country on one hand, and on the other of adjusting injustices by which native Maltese were deprived of any right to make their voices heard and to develop intellectually.

The suggestions made by this presumptious youth did not go down well at all with the Order and Vassalli was left with no other option but to enter into league with the Jacobites in the hope that the Maltese Islands would be taken away from the Order. However the plot was uncovered and Mikiel Anton was sentenced to life imprisonment. Many were of the opinion that Vassalli was a scholar, a thinker and a dreamer and that therefore he was not cut out for the intricacies of political life. Whatever one's opinion might be, the fact remains that his political involvement was a bitter experience that brought him disgrace, suspicion, prison sentences and escapes. Finally this benefactor of the Maltese people was exiled for twenty years from his beloved country. This was a dark period spent in France and Spain until, in 1820, aged 56, poor, in bad health and, deprived of the best years of his life, he was allowed to return.

Philosophy

Philosophically, Vassalli felt himself to be part of ‘the century of light’ and the ‘Republic of Letters’. He shared with the illuminists of his age a passion for intellectual enlightenment and learning, a broad base for formal education, and a longing for a social and political system more in line with egalitarian and fraternal principles. On the other hand, his philosophy does not show any pronounced aversion towards religion or the Catholic Church.

Vassalli came in contact with the doctrines of the ‘Age of Enlightenment’ while studying in Rome, Italy, between 1785 and 1795. He seems to have avidly read the major works of the encyclopaedists, and ventured to envisage their teachings in some concrete political form. Barely a year after terminating his studies in Rome, in 1796 Vassalli published an open letter, called Alla Nazione Maltese (To the Maltese Nation), as an introduction to his Maltese-Latin-Italian dictionary in which he exposed, perhaps for the first time, his philosophical and political views. The book also included a Discorso Preliminare (An Opening Word) in which he outlined his prospective reorganisation of Maltese society.

It was political and social change that Vassalli sought. Translating and applying the philosophical doctrines of the illuminists to the context of Malta, he advocated a wide social reform aimed at the establishment of a Maltese republic based on a broad educational system centred upon the concept of Maltese cultural identity.

Though philosophically Vassalli might not be considered to be too much of an original thinker – for he drew almost all of his basic concepts and ideas from contemporary French encyclopaedists and illuminists – nonetheless his freedom of thought and his understanding of how philosophy could be socially and politically viable might be indeed regarded as significant. Most certainly, he is probably to be respected and studied as one of the first Maltese philosophers who, apart of John Nicholas Muscat, carried philosophy into novel ambits of thought and action.

Monuments

There is a statue of Vassalli in his town of birth, Żebbuġ. His grave is to be found in the Msida Bastion Garden of Rest, a restored early 19th-century Protestant cemetery in Floriana that is maintained by the national trust Din l-Art Helwa.[6]

In literature

Frans Sammut wrote Il-Ħolma Maltija (The Maltese Dream) a novel which revolves around Vassalli's life. The novel was acclaimed by The Times as the best literary work ever written in Maltese. The novel has been published in an esperantist translation in New York and described by English writer Marjorie Boulton as "a colossal work". The novel's main thesis had been proposed by Sammut in an issue of the Journal of Maltese Studies dedicated to Vassalli, namely that Freemasonry played an important part in the patriot's life.[7] Sammut has also republished Vassalli's book on Maltese proverbs in a Maltese translation of the original Italian.

Ġużè Aquilina's novel, Taħt Tliet Saltniet ("Under Three Rules"), explores Vassalli's life when the Maltese Islands were ruled by the Order of Saint John, followed by the French and lastly by the British.

Vassalli's political figure is also celebrated in a number of poems: Lil Mikiel Anton Vassalli ("To Mikiel Anton Vassalli") is the common title of poems by Dun Karm Psaila, Ġorġ Pisani and Ninu Cremona. Rużar Briffa mentions Vassalli in the poem Jum ir-Rebħ (Victory Day).

In Music

Singer-songwriter Manwel Mifsud pays homage to him in his Maltese song Vassalli.

A Maltese rock opera by Paul Abela (music) and Raymond Mahoney (lyrics) named Bastilja (Bastille) recounts the effects of the French Revolution on the Maltese Islands during those times. Mikiel Anton Vassalli is one of the main characters, calling on the Maltese to follow their French comrades to fight for freedom.[8]

Further reading

- Ciappara, Frans (2014). M.A. Vassalli 1764-1829: An Enlightened Maltese Reformer. Midsea Books. p. 106. ISBN 978-99932-7-476-6.

- Fabricv, P. Grabiel (1931). "U Mikiel Anton Vassalli" (PDF). Il-Malti. 7 (2): 43. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2018.

See also

References

- pp. 60-61

- http://www.independent.com.mt/articles/2014-11-23/local-news/National-Geographic-names-Msida-Bastion-Cemetery-one-of-Europe-s-five-loveliest-cemeteries-6736126193

- David R. Marshall History of the Maltese language in local education 1971 p128 "Mikiel Anton Vassalli — And the Early Nineteenth Century Maltese grammars and dictionaries had already been written before the century, but all of them have long since been lost. It is for this reason that the honour of being the author of the first Maltese grammar goes to Canon Agius de Soldanis"

- István Fodor, Claude Hagège Réforme des langues 1994 p.615 "In the early nineteenth century the "Father of the Maltese language", Michel Antonio Vassalli, had actually converted to Protestantism and was employed by the British Bible Society to translate part .."

- Robert Thake, Un Républicain Maltais à Paris, Treasures of Malta, Vol. XXI, No. 2 (Easter 2015).

- Article on the Graveyard "The most famous Maltese buried here was Mikiel Anton Vassalli, known as the father of the Maltese language, who died on 12 Jan 1829, aged about 64. He was not on good terms with the local Catholic church and had translated the New Testament into Maltese against the wishes of the church. His wife was later also buried here in 1851."

- http://melitensiawth.com/incoming/Index/Journal%20of%20Maltese%20Studies/JMS.23-24(1993)/orig10sammut.pdf%5B%5D

- Mahoney and Abela are the same author and composer of the Maltese Epic "GENSNA"