Michael Shiner

Michael G. Shiner (1805–1880) was an African-American Navy Yard worker and diarist who chronicled events in Washington D.C. for more than 60 years, first as a slave and later as a free man. His diary entries have provided historians a first hand account of the War of 1812, the British Invasion of Washington, the burning of the U.S. Capitol and Navy Yard, and the rescue of his family from slavery as well as shipyard working conditions, racial tensions and other issues and events of 19th century military and civilian life.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

Michael G. Shiner | |

|---|---|

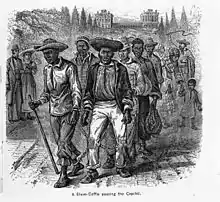

A group of enslaved men in front of the US Capitol in the 1830s | |

| Born | 1805 |

| Died | January 16, 1880 (aged 74–75) |

| Known for | Diary records of Washington D.C. for more than 60 years |

Early life, the Diary and Education

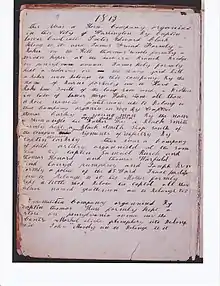

Shiner was born into slavery in 1805 and grew up near Piscataway, Maryland, working on a farm called "Poor Man's Industry" that belonged to slaveholder William Pumphrey Jr. Pumphrey brought young Shiner into the District of Columbia about 1813 to serve as a servant at his Grant Row lodgings.[8] The first entries date begin in this same year, the year of the British invasion of North America. Shiner however wrote these early entries as recollections (as opposed to contemporaneously) when he was an adult. Although often described as "The Diary of Michael Shiner", the first section of the manuscript is a narrative memoir written and arranged chronologically the important events he had witnessed in his youth. Shiner never called his manuscript a diary instead he simply inscribed the flyleaf "his book". Shiner concentrates primarily on significant public events in his life which he witnessed or read about, combined with some limited but important personal incidents and concerns. Shiner wrote using phonetic spelling and little punctuation. Because literacy for blacks outside of religious instruction was discouraged at the time, it is not known with certainty how Shiner learned to read and write. Some historians have speculated that he may have learned from a small school at the Navy Yard run by white abolitionists.[4] The 1870 report of Department of Education of the District of Columbia Special Report however confirms Shiner achieved literacy as an adult:

The Sabbath School among the colored people in those times differed from the institution as organized among whites as it embraced young and old and most of the time was given not to studying of the Bible but to learning to read. It was the only school which for a time they were allowed to enter.First Presbyterian Church of Washington at the foot of Capitol Hill opened a Sunday school for colored people in 1826 which held regular meetings every Sunday evening for years and in it many men women and children learned their alphabet and to read the bible. Michael Shiner one of the most remarkable colored men of the District who remembers almost everything that occurred at the Navy Yard during his service of some 60 years there is of this number.

War of 1812

During The War of 1812 Shiner recollected watching the British invasion of Washington DC: "They looked like flames of fire, all red coats and the stocks of their guns painted with red vermilion, and the iron work shined like a Spanish dollar."

Writing in 1878 he recounted "At the time of the battle of Bladensburg [ Wednesday 24 August] 1814 I was living with my master near where Grant Row now is in on East Capitol Street ... The British army followed our army and burned first the large dwellings at the corner of 5th and Maryland avenue Gen'l Ross 's horse was shot down from that house. They then burned the buildings then on A Street near the Capitol. I was an eye witness to all this. The British stayed, in Washington until Friday night and then left."[10]

When he and a young companion began to run, they were stopped by Mrs. Reed, an older white woman, who scolded them: "Where are you running you nigger you? What do you think the British want with such a nigger as you?" Shiner's friend hid in a baking oven, but Shiner continued to watch the events unfold.[7] Mrs. Reed was likely echoing white fear in the District, which heightened just before the Battle of Bladensburg 24 August 1814, "by an insistent rumor that a slave revolt had erupted in District of Columbia and the adjoining counties." The rumor was false yet many in the militia fled back into the city to protect their homes furthering the state of apprehension and dread.[11] As the war continued, Shiner described what he saw and learned in great detail. While there was no slave rebellion, the lure of freedom was real.[12] In 1813 Rear Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane had promised to emancipate slaves who joined their British forces. Some of the enslaved took advantage of the war to escape servitude and join the British forces.[13] One of these men was Archibald Clark enslaved to James Pumphrey 1765 -1832. James Pumphrey was the master of Michael Shiner's future wife Phillis and someone Shiner would have encountered often. During the War of 1812 information regarding Clark's successful escape to the British may have circulated among the brothers William and James Pumphrey's enslaved workforce and to the young Michael Shiner. Clark was both literate and wrote his family and his former master.[14]

Marriage and family

In his early twenties, he attended a Sunday school run by the First Presbyterian Church of Washington at the foot of Capitol Hill which had opened for free and enslaved blacks in 1826. He also mentions attending Ebenezer Methodist church services in the 1820s. Shiner generally kept his literacy secret, and wrote very little of a personal nature. Instead he chose to describe the public events he witnessed in the District and the navy yard.[4] About 1828 Shiner married a 20-year-old woman named Phillis (her surname is unknown), who had been purchased at the age of nine by William Pumphrey's brother James Pumphrey who also worked and lived in Washington DC. The young couple lived together near the naval yard and had six children. Later documentation reflects the Shiner family regularly attended the Ebenezer Methodist Church where they took part in church adult classes for free and enslaved black people.[4] Among those who attended Ebenezer in the 1820s and 1830s with the Shiner's were many employees of the shipyard; both black and white. Black attendees during these years were numerous, and included many community leaders such as: Moses Liverpool, Nicholas Franklin, Thomas Smallwood, Alethia Tanner and Sophia Bell.

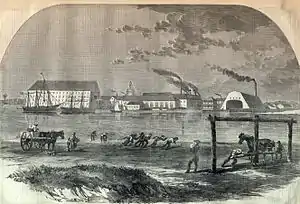

Work at the Navy Yard

From 1800-1830 the Washington Navy Yard was the District's main employer of enslaved African Americans. In 1808, muster lists show they made up one third of the workforce. The number of enslaved workers gradually declined during the next thirty years. William Pumphrey, like many slaveholders, rented his enslaved workers to the Navy Yard. In the "Muster Book of the U.S. Navy in Ordinary at the Navy Yard Washington City, Shiner is recorded as "Ordinary Seaman" with the notation he was first entered on the Ordinary rolls 1 July 1826.

In the early nineteenth century naval shipyard, the Ordinary was where naval ships were held in reserve, or for later need. Ships in Ordinary normally were older ships awaiting restoration that had minimal crews of semi-retired or disabled sailors who remained on board to make sure that the vessels were kept in usable condition, provided security, kept the bilge pump operating, and ensured the lines were secure. Here enslaved African Americans worked as seamen, cooks, servants or laborers, performing many of the most unpleasant and difficult jobs. The work they did included scraping the hull, moving timber, and helping to suppress fires. Their wages were paid directly to their owners.[4] At the navy yard enslaved workers were given limited medical treatment per the Secretary of the Navy's 1813 letter. This emergency medical care was provided solely to reassure and preserve the slaveholders property.[15] Michael Shiner was treated on at least two occasions 1827 and 1829 for "fever".[16] As an enslaved seamen Shiner's movements were on occasion carefully observed and recorded in the navy yard station log i.e. 27 and 28 December 1828.[17]

In his diary, Shiner, who later worked as a painter, chronicled the daily routine at the Navy Yard, providing important details of early working conditions and social attitudes at the Yard toward slaves and freeman. He tells of one incident where he was surrounded by a mob of thugs who "lit me up torch fashion with firecrackers" and another where he had to flee a gang of sailors who mistook him for a runaway slave. Other incidents he recounted included nearly drowning after falling in the freezing water and seeing a fellow worker accidentally decapitated while working.[18] Like many people who worked at the navy yard Shiner paid attention to the elements and is careful to record unusual weather such as the Year Without a Summer of 1816. For that year he wrote of the cold, unusual formations on the sun and crop failures, "wher a hard Winter for they Wher three black spots in the sun after the Winter closed the sun become to as red as blood ther Wher a frost every night the hold summer the Where no corn Made scarrly aBout in different section of the country it Where all Whitherd up." Weather was of particular concern since most employees enslaved and free worked outdoors regardless of the weather. In 1829 he records: "went out to the fire at that time a little before the bell rang for twelve and stayed at the garrison until between 1 and 2 o'clock in the night and the coldest night i ever felt in my life the hose were led from the garrison to reservoir at the market house it were so cold that the hose freeze up they formed lines in different sections passed the water with a bucket to the fire they worked like men there were a little Disturbance occurred between a fire[men] from the city and Samuel Brigs a firemen of the an a casta [Anacostia River] But that was soon settled by captain Wm Easby interfering Which at that time were Master Boat Builder of the Washington Navy yard that Wher a Hard Winter they wasn't 2 cord of Wood on the commercial Wharf they wasn't no Wood in the navy yard [ illegible] and they were not ten ton of coal in the yard they were condemn from War"

He also noted celestial phenomena e.g. Leonids meteor showers Nov. 12 1833: "The Meteors fell from the elements the 12 of November 1833 on Thursday in Washington. It frightened the people half to death."[19] Shiner also described military/civilian relationships and the efforts of early federal workers for better pay and employment conditions, including the 1835 Washington Navy Yard labor strike, which disintegrated into the Snow riots, a race riot of whites against blacks that was finally brought under control by President Andrew Jackson and the U.S. Marines. Writing in July 1835, Shiner recounts how white mechanics through threats intimidated black caulkers into quitting work on the USS Columbia"and they wher fifteen or twenty of them here at that time Caulkin on the Col lumbia USS Columbia and the Carpinters made all of them knock oft two." He added that,a group of striking white navy yard mechanics went after free black restaurant owner Beverley Snow and later threatened to attack Commodore Isaac Hull: "all the Mechanics of classes gathered into snows Restaurant and broke him up Root and Branch and they were after snow but he flew for his life and that night after they had broke snow up they threatened to come to the navy yard after commodore Hull."[4]

Shiner enjoyed the public events of the capitol and attended nearly all presidential inaugurations from John Quincy Adams to Abraham Lincoln's 2nd inaugural. He relates the large crowd as the president Lincoln stepped out onto the East Portico to deliver his soon to be famous address: "And on the fourth of March 1865 on Saturday the hon Abraham Lincoln taken his Seat Before he Came out on the porch to take his [seat] the wind blew and it rained with out intermission and as soon as Mr Lincoln came out the wind ceased blowing and the rain ceased raining and the Sun Came out and it was near as clear as it could be and calm and at the mean time there was a Star made its appearance west rite over the Capitol and it Shined just as bright as it could be ..." On 14 April 1865 after learning of Lincoln's assassination by Confederate sympathizer John Wilkes Booth, Shiner "clearly connected himself to the catastrophic event"[20] He wrote "Hon abraham Licoln [Lincoln] was assassinated on the 14 of April on good Friday knight at fords theater in washing[ton]and he died on the 15 of April 1865 on Saturday. "And on Friday evening before he was assassinated Mr Lincoln and his Lady where Both down at the Washington navy on good Friday the 14 1865."[21][22]

Slavery and freedom

When William Pumphrey died in 1827, he stipulated in his will that all eight his slaves were to be sold as 'term slaves' for a specific period of time, and afterwards manumitted. Michael Shiner was to be freed after another fifteen years of slavery.[23] William Pumphrey's manumissions may have been prompted by his Methodist faith, or more likely they served to insure the solvency of his estate by promising his bondsmen freedom after a specified time thus precluding fear of a massive slave sale and a follow on movement into the deep south.[24] Pumphrey had used prospective manumission as early as November 1816 when he sold two women Sarah Shins age 38. and her daughter Ellen Shins to a fellow slaveholder in the District of Columbia.[25] Shiner was subsequently bought by Thomas Howard, clerk of the Navy Yard in 1828 for $250. When Thomas Howard died in 1832, his will stipulated that Shiner be "...manumitted and set him free, at the expiration of eight years,[1836] if he conducted himself worthy of such a privilege".[26] The estate inventory enumerated Shiner as "Black Man M.Shiner Slave for four years [value] $ 100".[27]

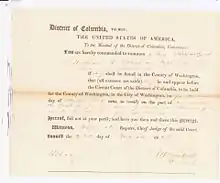

On 3 March 1833, William Pumphrey 's brother slaveholder James Pumphrey died. Following James' death Shiner writes his wife Phillis and their three children "wher snacht away from me and sold" on the street of Washington by slave dealers and confined to a slave pen in Alexandria. In fact Levi Pumphrey the estate heir was trying to sell Phillis and her children to settle estate debts.[28] Levi Pumphrey had sold Phillis Shiner and her children to the notorious slave dealers John Armfield and Isaac Franklin who probably planned to move the Shiner's into the deep South via the Natchez trace.[29] Levi Pumphrey was remembered by a former slave as "a perfect savage" he had close connections to slave dealers and owned a tavern at the corner of 6th and C street which was used by slave dealer Robert W. Fenwick.William Still The Underground Railroad : A record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c(Porter & Coates: Philadelphia1872)480.[30] Phillis Shiner was fortunate to secure the help of noted attorney Francis Scott Key, who filed a Petition For Freedom in District of Columbia Circuit Court, case of Phillis Shiner, Ann Shiner, Harriet Shiner and Mary Ann Shiner vs. Levi Pumphrey dated 1 May 1833.[31]

The petition stated "Phillis Skinner [Shiner], who sues for herself & her infant children Ann, Harriet & Mary Ann, complains of Levi Pumphrey, in custody &c of a plea of Trespass for this, to wit, that the said deft. on the day of at the County aforesaid, with force & arms, to wit with clubs, knives, sticks, & fists, made an assault upon the plffs & them her the said plffs did then & there beat, wound, & ill-treat & other injuries to the plffs then & there did against the peace of the U. States & to the damage of the plffs" and placed in the firms slave prison, at Alexandria. After being held a few weeks in the Alexandria slave prison with help Key and six wealthy and powerful connections Phillis and the three children were declared free by manumission.[32]

When Shiner thought Thomas Howard's heirs were reneging on his promised manumission, he tenaciously pursued his own freedom.[33] On 26 March 1836 in the Circuit Court of the District of Columbia he filed a petition for freedom, declaring that he was "unjustly, and illegally held in bondage" by the executors of Thomas Howard's estate, Ann Nancy Howard and William E. Howard.[34]

By 1840, Michael Shiner and his family were listed in the census as "free colored". As a freeman he continued to work at the Navy Yard as a painter where he was able to save money and provide for his family.[4]

Later life

Shiner's wife Phillis died some time before 1849. In 1850 he was living in Washington DC with his second wife Jane Jackson, aged 19, and children Sarah, Isaac and Braxton. After the Civil War, Shiner prospered, was active in the Republican Party and became an outspoken champion of black rights. During the Civil War Shiner's son Joseph C Shiner,(1836–1868) served as a private in the 3rd U.S.Colored Infantry. Shiner worked at the Navy Yard until some time after 1870. In his later years, it is believed he may have expanded upon some of the early entries in his diary, adding specifics which he did not know as a child.[4]

Death and legacy

Shiner died of smallpox on 17 January 1880. He was buried in the segregated Beckelts Cemetery AKA Union Beneficial Association Cemetery on C Street, SE.[35] The newspaper the Evening Star published a front-page obituary of Shiner, writing that he had "the most retentive memory of anyone in the city, being able to give the name and date of every event which came under his observation, even in his boyhood." After his death, the Shiner manuscript was sold to a "U.S. Army captain W.H. Crowley for $10.00" and subsequently came into the possession of the Library of Congress. In it, Crowley wrote: "This book is a very valuable book and is very interesting. It is worthy of perusal. The author Michael Shiner was a patriot may he rest in peace."[4] Following Shiner's death his wife Jane Jackson Shiner, filed the necessary papers to probate the estate and at her death, the estate went to her daughter Mary Ann Shiner Almarolia. In 1904 at Almarolia's death, local papers reported a protracted court battle[36] An article in The Washington Post, June 14, 1905, reports the estate increased substantially by the time of Shiner's death with an estimated value of $40,000.[37] The few articles that mention Michael Shiner for next three decades say nothing regarding the diary but only to relate somewhat sensational information on his or his daughter Mary Ann Shiner Almarolia's estate and legal disputes surrounding their property.[38]

At the Library of Congress, the diary was microfilmed sometime in the 1930s but remained largely unknown to the general public although periodically scholars quoted a few entries.[39] In 1941 the Library of Congress received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation for broadcasts of "Hidden History".[40] Noted author, stage star and raconteur Alexander Woolcott read selected entries from the Diary. The presentation was described as "A breathless tale of ante-bellum days in the District of Columbia written in bad, but lyrical English by Michael Shiner, a colored slave with a flair for pointed comment on monstrous events"[41][42] The Diary/manuscript was featured in the March 2002 Library of Congress exhibit, An African-American Odyssey. One section of the exhibit focused on Shiner's successful attempt to purchase his family from slave dealers.[43]

In 2004, the District Columbia established the 'Heritage Trail" to commemorate important Washingtonians. On what is called 'Barracks Row" (8th Street S.W.) and only one block from the navy yard, Michael Shiner's life is now commemorated on Heritage Trail marker number 9 with a brief biography and depiction of his now famous 'book".The Michael Shiner Residence site is now celebrated by Cultural Tourism DC. In 1867 Shiner purchased Square 946, a 9,000-square foot, triangular property bordered by Ninth, Tenth, and D Streets, SE, and South Carolina Avenue, SE, and built a house there. The address for the Shiner house was 474 Ninth Street, after 1871; it became 338 Ninth Street. By 1891 the property was out of the Shiner family, and Grace Baptist Church was built on the site. That building is now Grace Church condominium, 350 Ninth Street, SE.[44]

In 2007,for the first time "the book was completely transcribed and edited by John G. Sharp" for the Naval History and Heritage Command.[45] Currently Michael Shiner's life and legacy have been the subject of both increased popular and academic interest. Most recently (2015) for young readers Tonya Bolden's Capital Days Michael Shiner's Journal and the Growth of our Nation's Capital[46] and scholar Leslie Anderson's Life of Freed Slave Michael Shiner 2014.[47] Kim Roberts 2018 A Literary Guide to Washington DC contains a discussion and appreciation of Shiner both as a Washingtonian and writer.[48]

References

- "Slavery and the Making of America . The Slave Experience: The Family | PBS". www.thirteen.org.

- "Michael Shiner - Biographies - The Civil War in America | Exhibitions - Library of Congress". loc.gov. November 12, 2012.

- Bolden, Tonya (January 6, 2015). "Capital Days: Michael Shiner's Journal and the Growth of Our Nation's Capital". Harry N. Abrams – via Google Books.

- "The Diary of Michael Shiner Relating to the History of the Washington Navy Yard 1813-1869". public2.nhhcaws.local.

- "Lost Capitol Hill: False Accusations". January 25, 2016.

- "Life of Freed Slave Michael Shiner | C-SPAN.org". www.c-span.org.

- Steve Vogel, Through the Perilous Fight: Six Weeks That Saved the Nation, Random House, May 7, 2013 p. 165

- NARA 18 April 1878 letter of Michael Shiner to Board of Pensions re claim of Edward Foster.

- District of Columbia Department of Education, Special Report of the Commissioner of Education on the Condition of Public Schools in the District of Columbia, Submitted to the Senate June 6, 1868 and to the House with Additions June 13, 1870. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1870): 215, 221.

- Shiner Diary , Introduction quoting 18 April 1878 letter of Michael Shiner to Board of Pensions re claim of Edward Foster.

- Taylor Allan The Internal Enemy Slavery and War In Virginia, 1772 -1832 WW Norton & Co. New York 2013,p.305, 387.

- Franklin, John Hope and Schweninger, Loren Runaway Slaves Rebels on the Plantation Oxford University Press: New York 1999. p.28.

- William S. Dudley, editor The Naval War of 1812 A Documentary History Volume II. (Naval Historical Center: Washington DC 1992), 324-325.

- Taylor, p.384,544 n81.

- William Jones to Dr. Edward Cutbush, 23 May 1813 RG45 NARA

- The Register of Patients Naval Hospitals 1812 - 1934 Vol. 45., National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 52 Records of the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, Field Records Case Files for Patients at Naval Hospitals & Registers Entry 45.

- Sharp, John G. Washington Navy Yard Station Log Entries November 1822 - December 1889 Naval History and Heritage Command 2014 https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/w/washington-navy-yard-station-log-november-1822-march-1830-extracts.html

- J.D. Dickey, "Empire of Mud: The Secret History of Washington, D.C", Rowman and Littlefield, 2014, p. 128

- Tonya Bolden, Capital Days Michael Shiner's Journal and the Nation's Capital (Abrams Books New York City 2015),55.

- Martha Hodes "Lincoln's Black Mourners." Social Text 33.4 125 (2015): 69. Web.

- Shiner Diary, 184.

- Bolden, 61-63.

- Maryland State Archives Will of William Pumphrey 12 August 1827 Prince George's County Md. Liber TT#1 folio 423 and 424.

- T. Stephen Whitman The Price of Freedom Slavery and Manumission in Baltimore and Early Modern Maryland(The University Press of Kentucky:Lexington 1997),101

- Freedom & Slavery Documents in the District of Columbia Recorder of Deeds Office, Volume 3 1816 -1822 editor Helen Hoban Rodgers (Otter Bay Books: Baltimore 2009),217 no.627

- Archives of the District of Columbia District of Columbia Orphans Court (Probate) Court Records Group 2, Records of the Superior Court 1832 Box 11

- Will of Thomas Howard, Archives of the District of Columbia, District of Columbia Orphans Court (Probate) Court Records Group 2, Records of the Superior Court 1832 Box 11

- James Pumphrey Probate File NARA RG21 Entry 115, O.S. Case File 1569

- "200 Negroes Wanted" Franklin and Armfield ad Daily National Intelligencer 15 November 1832,1.

- Daily National Intelligencer 15 November 1832,4.

- Oh Say Can You See Early Washington Law and Family Petition For Freedom Case of Phillis Shiner, Ann Shiner, Harriet Shiner & Ann Shiner vs. Levi Pumphrey 1 May 1833 http://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0418.002

- Loren Schweninger Black Property Owners in the South 1790 - 1915(University of Illinois: Chicago 1990),89.

- Asch, Chris Myers & Muskgrove, George Derek Chocolate City A History of Race and Democracy in the Nations' Capital University of North Carolina Press: Chapel Hill, 2017,p.61.

- Oh Say Can You See Early Washington D.C., Law & Family Michael Shinor v Ann Howard & William E. Howard Petition for Freedom 26 March 1836 http://earlywashingtondc.org/doc/oscys.case.0175.001

- District of Columbia Death Certificate for Michael Shiner no. 22895 dated 17 January 1880.

- 31 August 1904 Evening Star Washington DC, 2. Almarolia vs. Holtzman et al. In Equity No. 23.908 District of Columbia Circuit Court

- Sharp, John G. History of the Washington Navy Yard Civilian Workforce 1799 -1962 Naval History and Heritage Command 2005, Appendix B accessed 20 July 2018 https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/browse-by-topic/heritage/washington-navy-yard/pdfs/WNY_History.pdf

- The Washington Times 5 September 1905,10.

- Gibbs Myers Pioneer's in the Federal Area,Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C. 44/45 (1942/1943): 136.

- " Charles T. Hassell "The Library of Congress Radio Research Project Hidden History" ALA Bulletin Volume 35, No. 7 July 1941, 448 452

- Sacramento Bee, (Hidden History) 31 May 1941, 20

- 1 June 1941 Daily Illinois State Journal, 18

- The Civil War Library of Congress , Michael Shiner accessed 20 July 2018 http://loc.gov/exhibits/civil-war-in-america/biographies/michael-shiner.html

- Cultural Tourism DC https://www.culturaltourismdc.org/portal/michael-shiner-residence-site

- Kim Roberts A Literary Guide to Washington, DC: Walking in the Footsteps of American Writers from Francis Scott Key to Zora Neale Hurston (University of Virginia Press; Charlottesville 2018),18.

- Bolden, Tonya Capitol Days Michael Shiner's Journal and the Growth of Our Nation's Capital (Abrams: New York 2015)

- Life of Freed Slave Michael Shiner Leslie Anderson 2014 C-Span https://www.c-span.org/video/?317598-1/life-freed-slave-michael-shiner

- Kim Roberts A Literary Guide to Washington, DC: Walking in the Footsteps of American Writers from Francis Scott Key to Zora Neale Hurston (University of Virginia Press; Charlottesville 2018),17-22.