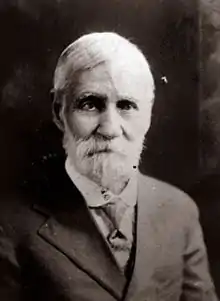

Merritt Kellogg

Merritt Gardner Kellogg (28 March 1832 – December 20 1921) was a Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) carpenter, missionary, pastor and doctor who worked in Northern California, the South Pacific, and Australia. He designed and built several medical facilities. Kellogg was involved in the controversy about which day should be observed as the Sabbath on Tonga, which lies east of the 180° meridian but west of the International Date Line.

Merritt Gardner Kellogg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 28 March 1832 Hadley, Massachusetts, US |

| Died | 1921 Healdsburg, California, US |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Carpenter, missionary, pastor and doctor |

Early years

Merritt Gardner Kellogg was born in Hadley, Massachusetts on the Connecticut River on 28 March 1832.[1] He attended the Battle Creek Sabbath School.[2] He converted to Seventh-day Adventism at the age of twenty. Kellogg was the stepbrother of John Harvey Kellogg.[3] He married Louisa Rawson (1832–94) and they had a child Charles Merritt Kellogg (1856–89).[1]

The Kelloggs made the westward journey to California in 1859, where they were probably the first Seventh-day Adventists in the state. In 1861 Kellogg gave a series of Bible lectures in San Francisco in which he converted fourteen people. In 1867 he returned east to New Jersey to take a short course in medicine at Trall's Hygieo-Thereapeutic College.[2] During his return journey to California he attended the SDA General Conference session on 1868 and asked that the church send evangelists to the West Coast.[4] Back in California he assisted the evangelists John Loughborough and Daniel Bourdeau, mostly talking on topics related to health.[2] During a smallpox epidemic in 1870 he gave water treatments and diet to his patients, of whom ten out of eleven survived. This earned him a high reputation.[5]

In the summer of 1877 Kellogg was asked to help look after patients at a San Francisco hydrotherapy center in exchange for room and board. The owner, Barlow J. Smith, sold out after five months and opened a retreat in Rutherford, in the Napa Valley. He invited Kellogg to come to Rutherford as a house physician. A patient there encouraged Kellogg to establish his own health resort, and helped arrange investors. Kellog began work on a site near St. Helena, California. Ellen G. White came to inspect the property, and endorsed the decision. The road and building were completed by the end of May 1878 and the first patients arrived on 7 June 1878. The health center was an immediate success.[6] Kellogg left when well-trained doctors arrived.[5] The Rural Health Retreat later became the St. Helena Hospital.[6]

South Pacific

In 1893 Kellogg was sent as a medical missionary to the South Pacific in the second voyage of the Pitcairn.[5] The ship carried books giving practical medical advice, which would be sold, and Kellogg would give lectures and treatments at the ship's places of call. The ship sailed from San Francisco on 17 January 1893 and reached Pitcairn on 19 February 1893. She went on to Tahiti, Huahine and Raiatea Islands.[7] The Pitcairn stopped at Rurutu Island, Mangaia Island, Rarotonga and Niue Island. Kellogg treated many sick people at each island. At Niue Kellogg observed that Christianity had been a corrupting influence. Spies reported misdemeanors to judges, who imposed a fine that was split between the judge and the spy. Kellogg wrote, "The result of this system is to cause the people to fear the law instead of fearing God, and as they have but a very dim idea of the object and power of the gospel, they learn to practice deceit so as to avoid detection and punishment."[7]

The Pitcairn bypassed Vavaʻu Island, Tonga, where there was a measles epidemic, to avoid being quarantined. She sailed via Fiji and Norfolk Island to New Zealand.[7] Kellogg stayed in Australia for a while, where he made a second marriage to a woman from Broken Hill, New South Wales.[2] His wife was Eleanor Kathleen Nolan (1874–1919). They had two children, Muriel and Merritt.[1] Kellogg was considered for an exploratory journey along the coast of Australia and on to New Caledonia in 1894, but it was decided later that year that New Caledonia was "not very promising".[8] He returned to the South Pacific with his wife, and reached Apia in Western Samoa in 1896. There he helped Dr. Frederick Braucht build a two-story sanitarium inland from the beachfront. This was the first such institution in the South Pacific.[2] The Pitcairn found Kellog and his wife on Samoa when it visited on its fifth voyage in 1896.[7]

In September 1897 Kellogg and his wife Eleanor Nolan Kellogg came to Tongatapu, the main island in Tonga, to assist with the medical work of the Seventh-day Adventist Church of Tonga. He built a timber home at Magaia that was long used as the home of the mission superintendent.[9] In Tonga Kellogg found difficulty earning a living as a doctor, in part due to competition from a government doctor who did not charge for his services.[10] His son Merritt Jr. was born in Nukuʻalofa in 1899.[11]

International Date Line controversy

Kellogg and fellow-missionaries Edwin Butz and Edward Hilliard debated which was the correct day to observe the Sabbath in Tonga. The practice on board the Pitcairn had been to change days at the 180° meridian. Islands such as Samoa and Tonga were well to the east of this line, so the missionaries observed the Sabbath on the day sequence of the Western Hemisphere. However, the Tonga islands used the same days as New Zealand and Australia, so the missionaries were observing the seventh-day Sabbath on the day the secular authorities called Sunday.[2]

The tract by Adventist John N. Andrews called The Definitive Seventh Day (1871) recommended using a Bering Strait date line.[2] If this line were taken as the IDL, the Tonga Adventists were celebrating the Sabbath on the wrong day. However, an international conference in 1884 had established the International Date Line (IDL) at 180° while allowing for local adjustments.[12] The Tonga missionaries sent letters to church leaders in Tahiti, Australia and the US asking for advice, and even asked Ellen G. White for her opinion.[2] Replies were contradictory. It was not until 1901 that White sent a letter to Kellogg in which she ruled decisively in favor of the 180° meridien.[12]

Later years

The Kelloggs transferred to Australia in May 1900.[11] They settled in Sydney, where Kellogg drew up the plans for the Wahroonga Sanitarium, and in 1901 supervised its construction.[12] This is now the Sydney Adventist Hospital.[5] Kellogg returned to California in 1903 and due to poor health lived in retirement.[4] He was suffering from hearing and vision problems. He lived the last nineteen years of his life in Healdsburg, California.[5] Kellogg was the older brother, or half-brother, of Dr. John Harvey Kellogg, who was expelled from the Battle Creek church on suspicion of unorthodox views and suspect practices at his sanitarium. Kellogg defended his brother in a 33-page essay he wrote in 1908.[13] Merritt Gardner Kellogg died in 1921.[4]

See also

- General Conference of Seventh-day Adventists

- Seventh-day Adventist Church

- Ellen G. White

- Seventh-day Adventist Church Pioneers

- Seventh-day Adventist eschatology

- Seventh-day Adventist theology

- Seventh-day Adventist worship

- History of the Seventh-day Adventist Church

- 28 fundamental beliefs

- Pillars

- Second Advent

- Baptism by Immersion

- Conditional Immortality

- Historicism

- Three Angels' Messages

- End times

- Sabbath in Seventh-day Adventism

- Adventist

- Seventh-day Adventist Church Pioneers

References

- Merritt Gardner Kellogg, Ancestry.

- Hay 1990, p. 4.

- Land 2014, p. 181.

- Land 2014, p. 182.

- Dr. Merritt Kellogg, SDA Encyclopedia.

- Odell 2004.

- Ford 2011.

- Steley 1989, p. 104.

- Hook 2007, p. 3.

- Steley 1989, p. 132.

- Hook 2007, p. 5.

- Hay 1990, p. 5.

- Kaspersen 1999.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Merritt Kellogg. |

Sources

- "Dr. Merritt Kellogg". SDA Encyclopedia (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2015-01-26.

- Ford, Herbert (2011). "The Good Ship Pitcairn". Pacific Union College. Retrieved 2015-01-26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hay, David E. (1990-01-27). "Merritt Kellogg and the Pacific Dilemma" (PDF). Record. Retrieved 2015-01-27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hook, Milton (2007). TALAFEKAU MO’ONI – EARLY ADVENTISM IN TONGA AND NIUE (PDF). South Pacific Division Department of Education. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-03-24. Retrieved 2015-01-21.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kaspersen, Åsmund (1999). "Pantheism and the "Alpha of Apostasy"". Ellen G. White -- the Myth and the Truth. Retrieved 2015-01-26.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Land, Gary (2014-10-23). "Kellogg, Merrit Gardner (1832-1922)". Historical Dictionary of the Seventh-Day Adventists. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4422-4188-6. Retrieved 2015-01-27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Merritt Gardner Kellogg". Ancestry. Retrieved 2015-01-27.

- Odell, Daphne (2004). "The Legacy of the California Kellogg". Adventist Review. Retrieved 2015-01-27.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steley, Dennis (1989), Unfinished: The Seventh-day Adventist Mission in the South Pacific, Excluding Papus New Guinea, 1886 - 1986, University of Auckland, retrieved 2015-01-22CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)