Megachile campanulae

Megachile campanulae, known as the bellflower resin bee, is a species of bee in the family Megachilidae. Described in 1903, these solitary bees are native to eastern North America. Studies in 2013 placed them among the first insect species to use synthetic materials for making nests. They are considered mason bees, which is a common descriptor of bees in several families, including Megachilidae. Within the genus Megachile, frequently also referred to as leafcutter bees, M. campanulae is a member of the subgenus Chelostomoides, which do not construct nests from cut leaves, but rather from plant resins and other materials. Females lay eggs in nests constructed with individual cell compartments for each egg. Once hatched, the eggs progress through larval stages and subsequently will overwinter as pupae. The bees are susceptible to parasitism from several other bee species, which act as brood parasites. They are medium-sized bees and the female adults are typically larger than the males. They are important pollinators of numerous native plant species throughout their range.

| Bellflower resin bee | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male M. campanulae | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Megachilidae |

| Genus: | Megachile |

| Subgenus: | Megachile (Chelostomoides) |

| Species: | M. campanulae |

| Binomial name | |

| Megachile campanulae | |

| Subspecies[2] | |

| |

| |

| Distribution of M. campanulae | |

| Synonyms[3] | |

|

Oligotropus campanulae | |

Taxonomy and naming

Megachile campanulae was originally described in 1903 under the name Oligotropus campanulae by Charles Robertson, an American entomologist from Carlinville, Illinois.[3][4] Megachile translates from Greek mega (μεγας) 'large' + cheil- (χειλ) 'lip'. In Latin, campanulae translates as "small bell". M. campanulae has been documented to frequent flowers in the genus Campanula, several species of which are commonly referred to as bellflowers.[5] Subspecies include M. campanulae campanulae and M. campanulae wilmingtoni.[2] The genus Megachile is a cosmopolitan group of solitary bees, often called leafcutter bees and resin bees. It is one of the largest genera of bees, with 1520 species in 56 subgenera worldwide.[6]

Life cycle and behavior

As a member of the subgenus Chelostomoides, M. campanulae are mason bees. This means that they use plant resins, mud, and pebbles for nest construction. Typically the females build small nests in pre-existing holes in trees, fences, or plant stems.[6] They will also nest in artificial "nest-traps" or "bee-blocks." They build the nests as a long single column of cells, along a tube. The deepest cells are constructed first, at which point the female lays a single egg sequentially in each cell. The cells are partitioned and sealed using some combination of the construction materials described above.[7] Pollen, sometimes mixed with nectar, provisioned in the cell will nourish the larvae when hatched. The bees are polylectic, meaning the larvae are fed from a variety of pollen sources.[8] Subsequently, after a few stages of molting, the larvae spin cocoons and pupate. They will overwinter as pupae. After several months, the bees will emerge in the adult form.[9]

Males typically emerge in advance of females. They will die shortly after mating. The female bees survive for another few weeks, during which time they build new nests and gather provisions.[10] Adult bees are active from April to September throughout most of the range. In Florida, that have been collected as early as February and as late as November. Flight times are typically May–October in cooler climates of their range.[5]

.jpg.webp)

Solitary bees, such as M. campanulae, do not form colonies. While social insects (ants, yellow jackets, honeybees) work in colonies, leafcutter and resin bees work independently building nests.[11] Similar to honeybees, female bees perform nearly all essential tasks of brood rearing. M. campanulae does not produce honey, but does perform other important beneficial tasks, pollinating crops and wild plants. Although they can produce a mild sting, less intense than that from a honeybee, they are considered nonaggressive.[12] Bees in the family Megachilidae carry pollen on the underside of their abdomen. Unlike honeybees, they do not have pollen baskets on their hind legs.[13] Most bees in the genus are small to medium in size, although M. pluto at 38 mm is regarded as the largest bee in the world.[14] Many bees in the genus are referred to as leafcutters. However, the mandibles of M. campanulae lack cutting edges;[5] it belongs to the subgenus Chelostomoides, which use mud or resins to build.[8]

Synthetic nest materials

In the wild, M. campanulae seal off their cells within the nest with natural resins found in plants and trees. In 2013, however, researchers reported that the bees had used synthetics, including caulk, to seal the cells. Compositional analysis of these materials revealed calcium, titanium, and iron. They resembled polyurethane-based sealants typically used in building construction.[15] It is not uncommon for insects to live inside found objects made of plastic. However, these findings are the first known of insects actually building nests with plastic.[16] With help from citizen scientists in Toronto, over 200 nest boxes were placed throughout the city. Scanning electron microscopy, x-ray microanalysis, and infrared microscopy were employed in identification of polymeric specimens. Researchers suggest the bees' behavior may be an example of adaptive behavior.[17] Since some of the bees were free of parasites, these novel and possibly more robust methods of nest building may offer additional protection.[18] Incorporation of plastic into the walls and sealants of the cell nests appeared to provide some protection against brood parasite invasion. However, use of these more readily available synthetic materials, in an urban setting, may be incidental. In fact, exposure of brood to polyurethane and polyethylene based plastics could be detrimental, as the Canadian team noted, since diffusion of moisture could be inhibited. Some of the brood specimens were heavily affected by mold growth.[18] Additionally, synthetic materials in the nest might hinder the bees ability to move and breath.[15] Toxin exposures and other effects of urbanization are well documented contributors towards pollinator decline in general.[19]

Distribution and habitat

The range of M. campanulae covers a broad expanse of the eastern North American continent. They are native to southern Ontario.[18] The range extends from this southeastern Canadian province, through the New England states to Florida. The range extends west, as far as Minnesota, Nebraska and Texas.[20] A few reports of sightings further west are noted, including presence in Colorado and Montana.[21]

Morphology and identification

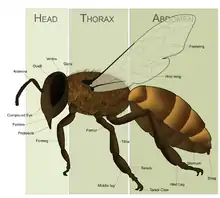

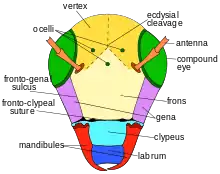

M. campanulae are medium-sized bees. Anatomically, they have a head, a middle section called a mesosoma, and a posterior section called a metasoma. The mesosoma is formed by fusion of the first abdominal segment or propodeum with the thorax. They have both compound eyes and simple eyes (ocelli), similar to many other insects. The mandibles in these resin gathering bees are characteristically lacking cutting edges found in the closely related leafcutters. The males are smaller than the females. The body segments are covered in various aspects with fine short hair called pubescence. The hairs are of varying length, texture, and color on different aspects of the male and female bees.

Morphologically, M. campanulae most resemble Megachile angelarum. There are also marked similarities in appearance between M. campanulae and M. exilis. The males of M. exilis have characteristically dilated and hollowed out front tarsal leg segments. The tarsi in M. campanulae are not modified and are otherwise unremarkable.[3][5]

Females

M. campanulae females measure 10–12 millimeters (0.39–0.47 in) in length. Although they resemble M. angelarum, the white banding (fascia) at the apex of the 5th tergal segment found on M. angelarum is absent in M. campanulae. Females can also can be recognized by parallel sided metasoma.[3]

Head

The mandibles have 4 tooth-like (dentate) ridges, which lack cutting edges. The compound eyes are nearly vertically aligned, but converge slightly towards front of the face or apex. The lateral ocelli are located closer to the compound eyes than to the vertex margin. One each side of the midline, there are distinct ridges (tubercles) located along the margin of the lower facial plate (clypeus). These tubercles are denticulate along the lateral margin. Other facial features include gena more narrow than the compound eyes. There are punctate markings on the vertex and the gena. Those on the vertex are uniform in shape with rough edges, slightly separated from one another. On the gena, they are less roughened and closer together. The frons shows more coarse and closely arranged punctures. Around the eyes, there are fine punctures, closely arranged. There are narrow areas above the clypeus with some shining spaces, but also areas of coarse and deep punctuation. The head is lightly covered with short, pale pubescence. Hairs are more dense on the face. Pubescence is also more prominent around the antennae, gena, and inner orbits. They are more white in these areas. They become more yellow on the vertex. They are sparse on the clypeus. The antenna segment F1 is twice as wide as it is long. It is approximately half the length of the pedicel. It is shorter than F2, F3, flagellomeres. The apical flagellomete is 1.5 times as long.[3]

Mesosoma

Along the lateral and posterior aspects of the mesosoma, the pubescence is short, white, and sparsely distributed. The hairs are more densely collected around the pronotal lobes. There are a paucity of pale, very short hairs on the mesoscutum. The hairs are stiffer, whiter and longer on the scutellum. Punctate markings across the mseoscutum and scutellum are coarse, deep, and closely arranged. The spaces between the mesoscutum and scutellum are shiny and very narrow. Punctate markings are finer on the axilla, where they are closely arranged. The pleura demonstrate punctate markings which are coarse and deep. These are densely arranged anteriorly. The pleura are shiny between the punctate markings. Lateral aspects of the propodeum are dull. They are overall smooth, except some fine and shallow punctures. These are closely arranged. The first tarsal segments are shorter and narrower than the tibiae. Yellow spurs are present on the legs. There are minute and closely spaced punctures on the skeletal plate covering the costal vein of the wing (tegula). The black veined wings are slightly cloudy at the apices and glassier at the bases.[3]

Metasoma

The second through fourth dorsal segments, or terga, are elongated and parallel to each other in orientation, separated by deep grooves. There are tomentose hairs in much of these grooves. There is white banding along the sides of the segments, towards the sides and posterior. The first tergum has a light covering of pale, erect hairs. It is more dense and tomentose at the lateral aspects. There is pale, barely noticeable pubescence on the second through fifth terga. There are depressions along the sides of the apical margin, which lack fascia. There are well defined punctate markings on each tergum. These are deep and distinctive and of variable size. They are close together along the sides and towards the back of the dorsal segments. They are uniformly distributed and coarse textured on the fifth tergum. There are pale hairs covering the posterior edge of the sixth segment densely enough to hide the surface. Yellowish-white modified scopal hairs for carrying pollen yellowish-white hairs, which are pale initially, darken in color along 6th sternal segment. Deep, coarse puncture marks on the sterna are uniformly distributed and closely spaced. The apical margins have a hyaline appearance and are depressed.[3]

Males

M. campanulae males measure 8–9 millimeters (0.31–0.35 in) in length. They also resemble M. angelarum. However, M. angelarum have around twice as many punctures between the lateral ocelli and vertex edges. They also have visible front coxal spines and short dark hairs at the 4th and 5th tergal segments.[3]

Head

The compound eyes of the male are very slightly convergent near the apex. There are 4-5 punctures present in the region separating the lateral ocelli and the vertex. The lateral ocelli are not quite equidistant between the eyes and the vertex margins. The clypea show tubercles near the midline. Puncture markings are very coarse, but become finer towards the apical margin. They are very closely spaced. The mandibles demonstrate three dentate ridges. The broadly triangular lower process is located along the midline. The gena are less broad than the compound eye. They show shallow indentations inferior to the mandibular base. Coarse punctures along the shiny vertex are deep and spaced at wide intervals. The puncture marks are not as coarse on the gena and they are more closely spaced. Deep punctate markings at the frons are tightly spaced and coarse. At the lateral aspects and above the clypeus, they are finely rugose. Pale pubescent markings are present on the head. Along the gena and vertex, the coverings are short and sparsely distributed. They are much more prominent and feathery in areas surrounding the antennae and the lower aspects of the face. The hairs are thick enough to obscure surface markings. They are even longer on the gena. The hairs are shorter on the lower mandibular surfaces and process. The anntenae have a pedicel that is about twice as long as F1. The width of F1 is about twice its length. It is shorter by a third in comparison to the remaining flagellomeres. The apical flagellomere is about twice as long as it is broad.[3]

Mesosoma

There are short, white pubescent hairs sporadically distributed along the lateral and posterior aspects of the mesosoma. They are more densely arranged along the upper surface of the prothorax. Hairs on the mesoscutum are short and infrequent. The hairs on the scutellum are longer and stiffer. Deep, ragged puncture marks are spaced closely together across the mesoscutum. The spaces between each punctate marking are less than the diameters of the marks. They are less closely associated on the scutellem. At the axilla, the markings are less ragged in appearance and are spaced very close together. The pleural surfaces are shiny, with puncture marks along the lower aspects being deep and ragged. Higher up, these markings are less ragged and less sparsely distributed. The lateral aspects of the propodeum are generally of a smoother texture, although there are crisp and shallow markings closely spaced. The spine along the anterior coxal aspect is nearly obliterated. The coxa are covered in dense white hairs. The anterior tarsus is dark. There are long brown hairs on the fronts of the first three tarsomeres. The more typical fringe of hairs along the posterior aspect is absent. There is a robust mid-tibial spur. The slim middle and posterior tarsi show yellow spurs. There are tiny puncture marks closely spaced together on the tegula. The black veined wings are slightly cloudy at the apices and glassier at the bases.[3]

Metasoma

The metasomal segment the first tergum is densely covered in long, white hairs. There are circumscribed areas on the second and third terga which are covered very slightly with pale and barely noticeable hairs. At the 4th and 5th terga, these pale hairs are more evident, longer and stiffer. The first three tergal segments are banded with white stripes along lateral apical aspects. There are deep grooves at the bases of all but the first tergum. These segments also show white banding. The margins are keel-like at the base. The apices have yellowish, hyaline appearance. The first and last terga have Punctate markings, which are sharply demarcated and closely spaced together. In between, coarse puncture marks are present of the other terga. They are deep and spaced at regular intervals, with spacings roughly one diameter of a puncture mark away from then next. The sixth tergum has small punctate marks close enough together that they are essentially contiguous, particularly towards the midline. The sixth tergum segment is vertically arranged. It is banded with white fascia at the base. It is covered elsewhere in pale tomentose hairs which darken medially. The seventh tergal segment is present transversely, but not appreciated medially. The first three sternal segments are clearly visualized and swollen at the edges. The apical margins are close covered with dense long white hairs. The fourth segment is unmodified but retracted, so non-apparent.[3]

The subspecies Megachile campanulae wilmingtoni (Mitchell) is characterized by larger size 11–12 millimetres (0.43–0.47 in), dark pubescence present on the 6th tergum, and darker wings with a brownish tinge. In the female, hairs on the pollen carrying apparatus (scopa) are black at the 6th sternal segment. Distribution is along the southeastern coast of the United States into Florida, where is assumes the predominant form.[5]

Parasites and diseases

Megachile campanulae can be parasitized by a number of brood parasites, including Monodontomerus obscurus, a Chalcid wasp.[22] The kleptoparasitic bee Stelis louisae has been found in the nests.[3] Members of the genus Coelioxys are also known parasites of Megachile. Kleptoparasitic bees characteristically deposit their eggs in the nests of other bees. As this behavior is similar to that of cuckoo birds, such bees are referred to as cuckoo bees. These host-parasite relationships are complex and the relationships between M. campanulae and other parasitic species may not be well described.[23]

Mold growth was shown to be problematic in the Toronto study, particularly when synthetic materials were incorporated in nest construction.[18] Chalkbrood is known to affect the related species, M. rotundata.[24]

Human interaction

.jpg.webp)

More focus is being directed on interactions between humans and native pollinators, such as M. campanulae. These relationships are complex, involving issues of habitat loss, pesticides and toxin exposures, climate change, and other effects on the environment.[25] The species M. campunulae pollinates of a wide array of flowers and crops. The significance of contributions from native pollinators is gaining increased attention in the wake of declines in managed bee populations. Such declines have received substantial press, especially in relation to colony collapse disorder. In 2013, Oregon Congressman Earl Blumenauer introduced H. R. 2692 the "Save America's Pollinators Act".[26] In addition, an International Pollinator Initiative has been developed by the Food and Agriculture of the United Nations working group.[27] A similar project, the North American Pollinator Protection Campaign might more directly address issues specific to M. campanuale.[28]

On a smaller scale, human behaviors adversely affecting populations of bees, such as M. campanulae, can be mediated in other ways. Many native bee species can be managed with minimal equipment. M. campanulae will nest in simple bee boxes. These are constructed in simplest form by drilling holes in a block of wood. The wood is attached to a post or wall, ideally in an area receiving adequate sun. Holes of different diameter will be suited better for different bee species.[29] Since native pollinators forage in an area within about 500 yards (460 m) of the nest, they can increase the productivity of a small garden.[13]

Sparse literature has been devoted to effects of pesticides on M. campunulae specifically. However, in general pesticide exposure is detrimental to native bee populations. Bees can be harmed by numerous classes of pesticides including: insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, acaricides, rodenticides (coumarins).[30]

Pollination

Megachile bees pollinate of a broad array of flowering plants from different families.[12] M. campanulae has been documented to pollinate the following:[5]

- Asclepias – Milkweed

- Baptisia – Wild indigo

- Campanula – Bellflower

- Galactia – Wild peas

- Malva – Mallow

- Melilotus – Sweet-clover

- Oenothera – Evening primrose

- Lobelia – Lobelias

- Lythrum – Loosestrife

- Nepeta – Catmints

- Pontederia – Pickerel weeds

- Psoralea – White tumbleweed

- Pycnanthemum – Mountain mints

- Rudbeckia – Coneflowers, black-eyed-susans

- Solidago - Goldenrods

- Strophostyles – Trailing wild bean

- Symphoricarpos – Snowberry, waxberry or ghostberry

- Verbena – Verbena or vervain

See also

References

- "Megachile campanulae (Robertson, 1903)". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- Mitchell, Theodore B (1962). The Bees of the Eastern United States II (PDF). Technical bulletin (North Carolina Agricultural Experiment Station). pp. 182–184. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Sheffield, Cory S.; Ratti, Claudia; Packer, Laurence; Griswold, Terry (29 November 2011). "Megachile (Chelostomoides) campanulae (Robertson, 1903)". Canadian Journal of Arthropod Identification. York University. doi:10.3752/cjai.2011.18. ISSN 1911-2173. Retrieved 26 September 2014.

- Marlin, J. C. and W. E. LaBerge (2001), "The native bee fauna of Carlinville, Illinois, revisited after 75 years: a case for persistence", Conservation Ecology, 5 (1): 9

- "Megachile campanulae (Robertson, 1903)". DiscoverLife.Org. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- "Genus Megachile – Leaf-cutter and Resin Bees". BugGuide.Net. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- Sheffield, Cory S.; Ratti, Claudia; Packer, Laurence; Griswold, Terry (29 November 2011). "Leafcutter and Mason Bees of the Genus Megachile Latreille (Hymenoptera: Megachilidae) in Canada and Alaska". Canadian Journal of Arthropod Identification. York University. doi:10.3752/cjai.2011.18. ISSN 1911-2173. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- "Chelostomoides". UF/IFAS Entomology and Nematology Department. Univ of Florida. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- Michener, Charles D. (June 1, 2000). The Bees of the World (1st ed.). The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 4–8. ISBN 0801861330.

- Mader, Eric; Spivak, Marla; Evans, Elaine (Feb 2010). Managing Alternative Pollinators: A Handbook for Beekeepers, Growers, and Conservationists (PDF). SARE Handbook 11, NRAES – 186. pp. 70–93. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Cranshaw, W.S. "Leafcutter Bees". Colorado State University Extension. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- "Megachile bees Factsheet". BioNET-EAFRINET. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- "Encouraging Native Pollinators". Univ of Arkansas. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Cranshaw, Whitney; Redak, Richard (2013). Bugs Rule!: An Introduction to the World of Insects. Princeton University Press. p. 307. ISBN 9781400848928.

- "City bees line nests with plastic bags". University of Washington Conservation Magazine (Conservation This Week). February 13, 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Goldman, Jason G (Jun 1, 2014). "Bees Living in Cities Are Building Their Homes with Plastic". Scientific American. 310 (6). Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- "Study: Bees Using Plastic To Help Build Their Nests". CBS DC. February 5, 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014. External link in

|publisher=(help) - MacIvor, J Scott; Moore, Andrew E. (31 December 2013). "Bees collect polyurethane and polyethylene plastics as novel nest materials". Ecosphere. 4 (12). doi:10.1890/ES13-00308.1. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Vanbergen, Adam J; Insect Pollinators Initiative (2013). "Threats to an ecosystem service: pressures on pollinators" (PDF). Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. doi:10.1890/120126. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- Murray, Tom. "Species Megachile campanulae – Bellflower Resin Bee". BugGuide.net. Retrieved 20 September 2014.

- Scott, Virginia L.; Ascher, John S.; Griswold, Terry; Nufio, César R. (September 1, 2011). "The Bees of Colorado (Hymenoptera: Apoidea: Anthophila)" (PDF). Natural History Inventory of Colorado. University of Colorado Museum of Natural History (23). ISSN 0890-6882. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 24 October 2014.

- Macivor, J. Scott; Salehi, Baharak (1 August 2014). "Bee Species-Specific Nesting Material Attracts a Generalist Parasitoid: Implications for Co-occurring Bees in Nest Box Enhancements". Environmental Entomology. 43 (4): 1027–1033. doi:10.1603/EN13241.

- "Bees of the Week: genus Coelioxys". The bees needs. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- James, Rosalind R. "Temperature and chalkbrood development in the alfalfa leafcutting bee,". Apidologie. 36 (1): 15–23. doi:10.1051/apido:2004065.

- "Human-insect interactions: Bees". cnn.com. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- "Text of the Saving America's Pollinators Act of 2013". govtack.us. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- "Pollination and Human Livelihoods". Pollination Information Management System. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- "North American Pollinator Protection Campaign NAPPC". North American Pollinator Protection Campaign. Retrieved 6 November 2014.

- "How to make a Bee Hotel". The Pollinator Garden. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- "Why worry about native bees?". Native Bee Conservancy. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Megachile campanulae. |