Medieval European magic

During the Middle Ages magic in Europe took on many forms. Instead of being able to identify one type of magician, there were many who practiced several types of magic in these times, including: monks, priests, physicians, surgeons, midwives, folk healers, and diviners.[1]

The practice of “magic” often consisted of using medicinal herbs for healing purposes. Classical medicine entailed magical elements, they would use charms or potions in hopes of driving out a sickness.

Medieval Magic

Medical Magic

Medicinal practices in the Middle Ages were often regarded as forms of “natural magic”. One in particular was referred to as a “leechbook”, or a doctor-book that included masses to be said over the healing herbs. For example, a procedure for curing skin disease first involves an ordinary herbal medicine followed by strict instructions to draw blood from the neck of the ill, pour it into running water, spit three times and recite a sort of spell to complete the cure. In addition to the leechbook, the Lacnunga included many prescriptions derived from the European folk culture that more intensely involved magic. The Lacnunga prescribed a set of Christian prayers to be said over the ingredients used to make the medicine, and such ingredients were to be mixed by straws with the names “Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John” inscribed on them. In order for the cure to work, several charms had to be sung in Latin over the medicine.[2]

Charms

Prayers, blessings, and adjurations were all common forms of verbal formulas whose intentions were hard to distinguish between the magical and the religious. Prayers were typically requests directed to a holy figure such as God, a saint, Christ, or Mary. Blessings more often were addressed to patients, and came in the form of wishes for good fortune. Adjurations, also known as exorcisms were more directed to either a sickness, or the agent responsible such as a worm, demon, or elf. While these three verbal formulas may have had religious intentions, they often played a role in magical practices. When the emphasis of a prayer so apparently relied on the observance of religiously irrelevant conditions, we can characterize it as magical. Blessings were more often than not strictly religious as well, unless they were used alongside magic or in a magical context. However, adjurations required closer scrutiny, as their formulas were generally derived from folklore. The command targeted at the sickness or evil left the possibility of refusal, meaning the healer entered a battle with the devil in which he or she relied on a holy power to come to his/her aid. Though people at this age were less concerned with whether or not these verbal formulas involved magic or not, but rather with the reality of if they were or were not successful.

Sorcery

Not only was it difficult to make the distinction between the magical and religious , but what was even more challenging was to distinguish between helpful (white) magic from harmful (black) magic. Medical magic and protective magic were regarded as helpful, and called ‘white’, while sorcery was considered evil and ‘black’. Distinguishing between black magic and white magic often relied on perspective, for example, if a healer attempted to cure a patient and failed, some would accuse the healer of intentionally harming the patient. In this era, magic was only punished if it was deemed to be ‘black’, meaning it was the practice of a sorcerer with harmful intentions [3]

Early Opposition to Magic

One of the main reasons magic was condemned was because those who practiced it put themselves at risk of physical and spiritual assault from the demons they sought to control. However, the overarching concern of magical practices was the grievous harm it could do to others. Magic represented a huge threat to an age that widely professed belief in religion and holy powers.

Legal Prohibitions of Magic

Legislation against magic could be one of two types, either by secular authorities or by the Church. The penalties assigned by secular law typically included execution, but were more severe based on the impact of the magic, as people were less concerned with the means of magic, and more concerned with its effects on others. The penalties by the Church often required penance for the sin of magic, or in harsher cases could excommunicate the accused under the circumstances that the work of magic was a direct offense against God. The distinction between these punishments, secular versus the Church, were not absolute as many of the laws enacted by both parties were derived from the other [3]

The persecution of magic can be seen in law codes dating back to the 6th century, where the Germanic code of Visigoths condemned sorcerers who cursed the crops and animals of peasant's enemies. In terms of secular legislation, Charles the Great (Charlemagne) was arguably the strongest opposing force to magic. He declared that all who practiced sorcery or divination would become slaves to the Church, and all those who sacrificed to the Devil or Germanic gods would be executed.[3]

Charlemagne's objection to magic carried over into later years, as many rulers built on his early prohibitions. King Roger II of Sicily punished the use of poisons by death, whether natural or magical. Additionally, he proclaimed that ‘love magic’ be punished regardless of if anyone was hurt or not. However, secular rulers were still more concerned with the actual damage of the magic rather than the means of its infliction.[3]

Instructions issued in 800 at a synod in Freising provide general outlines for ecclesiastical hearings. The document states that those accused of some type of sorcery were to be examined by the archpriest of the diocese in hopes of prompting a confession. Torture was used if necessary, and the accused were often sentenced to prison until they resolved to do penance for their sins.[3]

Prosecution in the Early Middle Ages

Important political figures were the most frequently known characters in trials against magic, whether defendants, accusers, or victims. This was because high-society trials were more likely to be recorded as opposed to trials involving ordinary townspeople or villagers. For example, Gregory of Tours recorded the accusations of magic at the royal court of 6th century Gaul. According to History of the Franks, two people were executed for supposedly bewitching emperor Arnulf and prompting the stroke that lead to his death.[3]

Magic in the Later Middle Ages

The concept of magic was further developed in the high and late Middle Ages. The rise of legal commentaries and consultations during this time lead to the inclusion of law in Universities’ curricula. This fueled a detailed reflection of the principles underlying prosecution for magic. The early fourteenth century brought about the pinnacle of trials involving magic. In this time, several individuals were charged with using magic against both Pope John XXII and the King of France. These trials only enhanced the already growing concern about magic, and thus perpetuated the increasing severity of punishments for such actions. The increase in trials in the late Middle Ages was also in part due to the shift from accusatory to inquisitorial procedures. In accusatory procedures, the accuser had to provide ample evidence to prove the guilt of the accused. If the accuser failed to do so, or did not have any proof, he or she would have to face the punishment that would have been assigned to the accused had he/she been found guilty. The inquisitorial procedure allowed judges to undertake prosecution on their own initiative without consequences. This made it easier for the accuser to secure conviction for sorcery, and not have to worry about having insufficient evidence thus putting their own innocence in jeopardy. Inquisitorial interrogation took many forms, including experiments with reflecting surfaces, invocation of demons, use of human heads to obtain love or hatred, and more.

Another possible reason for the rise in frequency of trials regarding magic in the later fourteenth century was due to a change from parchment to a cheaper medium of paper. This made it cheaper for more information to be recorded and preserved, therefore we have a greater volume of documented information from this era. While this may have caused a slight increase in trials against magic, the main reason was in fact the new inquisitorial procedure of trial and prosecution as mentioned above.[3]

The Rise of Witch Trials

The fourteenth century already brought about an increase of sorcery trials, however the second and third quarters of the fifteenth century were known for the most dramatic uprising of trials involving witchcraft. The trials developed into catch-all prosecution, in which townspeople were encouraged to seek out as many suspects as possible. The goal was no longer to secure justice against a single offender but rather to purge the community of all transgressors. The term “witchcraft” has multiple connotations, all involving some type of sorcery or magic. However, by the late Middle Ages this term developed into someone who went beyond mere sorcery and acted in league with other witches on behalf of the Devil. Friars preached that not only are the witches who work for the devil guilty, but also all those who fail to report these culprits. This led to an outbreak of accusations, in fear of being accused themselves. Trials inspired more trials, and this increase in trials inspired the rise in the frequency of literature on witches. The famed culmination of this literary tradition was the Malleus maleficarum written in 1486 by Jacob Sprenger and Henry Kramer. This classic case of misogynist witchcraft treatise and its impact on magic in the Middle Ages will be explored later in this article. The growing popularity of literature regarding witchcraft and magic lead to an even greater upsurge in trials and prosecutions of witches.[4]

The stereotype of the witch finally solidified in the late Middle Ages. Numerous texts singled out women to be especially inclined to witchcraft. In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, women defendants outnumbered men two to one. This difference only became more pronounced in the following centuries. The disparity between women and men defendants was primarily due to the position women held in late medieval society. Women in this era were far less trusted than men, as they were presumably weak minded and easily dissuaded. General misogynist stereotypes further encouraged their prosecution, which lead to a more stiffened stereotype of witches. Massive witch trials swept across Europe in the second half of the fifteenth century. In 1428, more than 100 people were burned for killing others, destroying crops, and working harm by means of magic. This trial in the Valais provided the first evidence for the fully developed stereotype of a witch, including flight through the air, transforming humans into animals, eating babies and the veneration of the Devil. The unrestricted use of torture in combination with the adoption of inquisitorial procedures as well as the development of the witch stereotype and a dramatic rise in public suspicion ultimately caused the swelling fervor and frequency of these sweeping witch hunts.[3]

Malleus Maleficarum

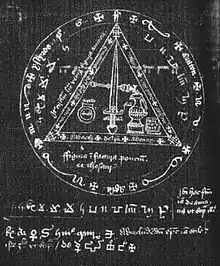

Practices such as alchemy, medicinal magic, charms, and sorcery have been dated back centuries before they were considered evil. The Catholic Church condemned such practices in about 900 AD (3), but it was not until Malleus Maleficarum was published in 1487 that individuals who practiced things considered as “witchcraft” were punished severely. Malleus Maleficarum was published by a Catholic clergyman in Germany. It was written in Latin and the title roughly translates to “Hammer of the Witches”.[5] Before the publication of Malleus Maleficarum, an individual was barely punished if accused of practicing any form of magic. Post-publication of this document changed the way that medieval society treated anyone who performed anything considered an act of magic or witchcraft. Malleus Maleficarum was used as a judicial book of guidelines within secular courts of Europe over three hundred years past its date of publication.[5] Its main two purposes were to inform the audience about how to detect individuals who practice magic and how to prosecute said individuals. The document was divided into three parts, each of which dealt with something different within the process of persecution. The first section discusses what makes witchcraft real and how it is a very present threat to their current society. This section also makes the connection between witches and the Devil. In the second part, actual acts of magic are discussed. Chapters within this section are titled with various spells that the witches might perform, such as “How they are transported from Place to Place”, “How Witches Impede and Prevent the Power of Procreation”, “Of the Manner whereby they Change Men into the Shapes of Beasts”, etc.[6] They identify various magical practices with the idea of witchcraft, thus condemning many acts of magic that have been performed for centuries as crimes punishable by death. This section also discusses various remedies by which one can protect themselves against the actions of witches, many of these remedies being reminiscent of various magical acts.[4] The third section discusses the actual prosecution of witches, and the procedure by which one must follow. It defines the use of prosecution, defense, witnesses, and punishments. It is essentially a guide on how to convict an individual of witchcraft.

References

- Flint, Valerie I. J. (1991). The Rise of Magic in Early Medieval Europe. Clarendon Press. ISBN 0198205228.

- Kieckhefer, Richard (2000). Magic in the Middle Ages (Canto ed.). Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78576-1.

- Kieckhefer, Richard (1989). Magic in the Middle Ages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78576-1.

- Pavlac, Brian (2009). Witch Hunts in the Western World: Persecution and Punishment from the Inquisition through the Salem Trials: Persecution and Punishment from the Inquisition through the Salem Trials. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313348747.

- Mackay, Christopher S. (2006). Malleus Maleficarum (2 volumes). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-85977-8. (Latin) (English)

- Malleus Maleficarum (1486) translated by Montague Summers (1928) http://www.sacred-texts.com/pag/mm/