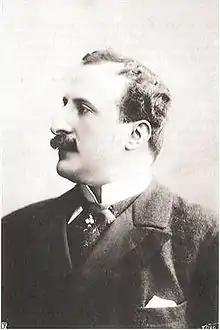

Mattia Battistini

Mattia Battistini (27 February 1856 – 7 November 1928) was an Italian operatic baritone. He was called "King of Baritones".[1][2]

Early life

Battistini was born in Rome and brought up largely at Collebaccaro di Contigliano, a village near Rieti, where his parents had an estate.

His grandfather, Giovanni, and uncle, Raffaele, were personal physicians to the Pope and his father, Cavaliere Luigi Battistini, was a professor of anatomy at the University of Rome. Battistini attended the Collegio Bandinelli and later the Istituto dell' Apollinare.

Battistini dropped out of law school to study with Emilio Terziani (who taught composition) and with Venceslao Persichini (professor of singing) at the Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia—then the Liceo Musicale of Rome. Battistini worked with conductor Luigi Mancinelli and the composer Augusto Rotoli, and he consulted with baritone Antonio Cotogni, in an effort to refine his technique.

Early career

Most of the following information about Mattia Battistini's performance venues, dates and roles is drawn from The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Opera (second edition, 1980), edited by Harold Rosenthal and John Warrack, and The Record of Singing (Volume One, 1977), by Michael Scott.

A 22-year-old Battistini made his operatic début at the Teatro Argentina, Rome, as Alfonso in Donizetti's La favorita on 11 December 1878. However, this date is erroneously given by many reference books and articles as correct, but reveals careless and repeated copying from faulty sources. It has been proven by the painstaking research of Jacques Chuilon that the date should most likely be replaced by Saturday, 9 November 1878. For full argumentation please see page 7 of the definitive Battistini biography Mattia Battistini, King of Baritones and Baritone of Kings, 2009 (The Scarecrow Press, Lanham, Md, USA), translation by E. Thomas Glasow; also to be found on page 17 of the author's original French edition Battistini, le dernier divo, 1996 (Editions Romillat, Paris).

During the first three years of his professional career he toured Italy, honing his voice and gaining invaluable experience by singing principal rôles in such varied operas as La forza del destino, Il trovatore, Rigoletto, Il Guarany, Gli Ugonotti, Dinorah, L'Africana, I Puritani, Lucia di Lammermoor, Aïda, and Ernani. He participated, too, in several operatic premières. In 1881 he went to Buenos Aires for the first time, touring South America for more than 12 months. On his return trip, he appeared in Barcelona and Madrid where he sang Figaro in Rossini's comic masterpiece Il Barbiere di Siviglia. His success in this was enormous and it marked the beginning of his ascent to major operatic stardom.

In 1883, he undertook his first visit to the Royal Opera House at London's Covent Garden, where he appeared as Riccardo in Vincenzo Bellini's I Puritani in a stellar cast containing Marcella Sembrich, Francesco Marconi and Edouard de Reszke. He also sang opposite Adelina Patti, the leading soprano of her era, in other Covent Garden productions. In such exulted and entrenched company there was not much attention paid to a new, unheralded young baritone! However, he would receive much greater réclame in London during subsequent Covent Garden appearances in 1905–1906, when the now mature performer established himself as a darling of Edwardian-era high society due to his dashing vocalism and polished off-stage demeanour.

Unlike his initial London experience, when Battistini made his debut at the important Teatro San Carlo in Naples in 1886, he scored an immediate triumph. Two years later, he once more sailed to Buenos Aires to fulfil a series of singing engagements; but this proved to be his last trans-Atlantic excursion, and he never appeared again in South America. He avoided North America, too, despite receiving overtures from the management of the New York Metropolitan Opera, where Battistini's core repertoire was allocated in his absence to the Italian baritones Mario Ancona, Giuseppe Campanari, Antonio Scotti and, after 1908, Pasquale Amato.

Battistini is said to have developed a permanent horror of oceanic travel due to his adverse experiences on that particularly rough 1888 voyage to Buenos Aires. Eighteen Eighty-Eight was a memorable year for Battistini in another way, however, for it proved to be the year of his début at Italy's foremost opera house—La Scala, Milan. La Scala's audiences acclaimed him and he was re-engaged for the next season.

The Russian years

From 1892 onwards, Battistini established himself as an immense favourite with audiences at Russia's two imperial theatres in Saint Petersburg and Moscow: the Mariinsky and the Bolshoi respectively. He returned to Russia regularly, appearing there for 23 seasons in total, and touring extensively elsewhere in eastern Europe, using Warsaw as his stepping-stone. He would journey to Warsaw, Saint Petersburg, Moscow and Odessa like a prince, travelling in his own private rail coach with a retinue of servants and innumerable trunks containing a vast stage wardrobe renowned for its elegance and lavishness. Indeed, the composer Jules Massenet was prepared to adjust the rôle of Werther for the baritone range, when Battistini elected to sing it in Saint Petersburg in 1902, such was the singer's prestige.

The industrious Battistini also appeared with some regularity in Milan, Lisbon, Barcelona, Madrid, Berlin, Vienna, Prague, Budapest and Paris (where he sang for the first time in 1907). But his many social connections in Russia, and the favour that he enjoyed with the imperial family and the nobility, ensured that Russia—more than perhaps even Italy—became his artistic home prior to the outbreak of the First World War, in 1914. The war led to the destruction, by the Bolsheviks in 1917, of the Tsarist regime and the aristocratic society which had enriched touring Italian opera stars like Battistini and his tenor compatriots Francesco Tamagno, Francesco Marconi and Angelo Masini. This history-shaping political development, coupled with Battistini's refusal to sing in the Americas, meant that his career after the war's conclusion in 1918 was confined to Western Europe.

Incidentally, Battistini's choice of bride had befitted his esteemed social status in Tsarist Russia and the West: he married a Spanish noblewoman, Doña Dolores de Figueroa y Solís, who was the offspring of a marquis and a cousin of Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val.

Final years and death

Battistini formed his own company of singers following the 1914–1918 war. He toured with them and appeared frequently in concerts and recitals. He sang in England for the final time in 1924, and gave his last concert performance one year before his death. His voice was reportedly still steady, responsive and in good overall condition.

His last singing engagement occurred in Graz, Austria, on 17 October 1927. He withdrew to his estate at Collebaccaro di Contigliano, Rieti, dying there from heart failure on 7 November 1928.

Battistini also taught voice in later years; among his pupils were the Basque baritone Celestino Sarobe[3] and the Greek baritone Titos Xirellis.[4]

Recordings

Battistini's initial sequence of records were cut in Warsaw in 1902 for the Gramophone and Typewriter Company. He then, in the 1906–1924 period, recorded extensively for the Gramophone Co Ltd and its associated companies. His records were issued in the USA by Victor. Battistini's last recording session took place during February 1924. The earliest of his discs feature a piano accompanist but his later sung offerings were backed by a small band of orchestral musicians and, occasionally, a few choristers.

Selected reissues

On vinyl long-playing disc

EMI, the original producer, issued a complete Battistini collection late in the LP era, skillfully remastered from the original 78-rpm shellac discs by audio technician Keith Hardwick.

On compact disc

- Mattia Battistini: The Complete Recordings 1898–1924, 6 CDs, Marston Records 2015 (USA).[5]

- The Complete Recordings: Mattia Battistini, Volume 1 (1902–1911), Romophone (UK).

- Mattia Battistini: a recital of arias by Mozart, Flotow, Donizetti, Gounod, Verdi, Ambroise Thomas, Preiser—Lebendige Vergangenheit (Austria).

- Mattia Battistini: Il Re dei Baritoni, Preiser—L.V. Austria; a 2-CD edition that boasts a discerningly chosen and well transferred cross-section of the singer's large recorded output.

- Mattia Battistini, Volumes 1–3, Pearl (UK).

- Mattia Battistini Rarities, Volumes 1–2, Symposium (UK).

This singer is found, too, on many historical CDs devoted to vocal compilations.

An appreciation of his recordings

Mattia Battistini was esteemed as one of the greatest of singers and even a cursory acquaintance with his many discs will make it clear why he was so celebrated by his contemporaries. Amongst the arsenal of vocal weapons that he displays on record were the perfect blending of his registers coupled with the sophisticated use of ornamentation, portamento and fil di voce, as well as an array rubato and legato effects. His art was perfected before the advent of "passion-torn-to-tatters" verismo opera in the 1890s, and together with the likes of Pol Plançon and Mario Ancona (and, to a lesser extent, Alessandro Bonci), he represented the twilight of the art of male bel canto singing on disc.

Fortunately the sound of Battistini's clear, high-placed and open-throated baritone voice took well to the primitive acoustic recording process with only his very lowest notes sounding pallid. He also handled the trying conditions of the early sound 'studios', with their boxy confines and wall-mounted recording funnel, much better than did many of his contemporaries, who often felt inhibited or intimidated by their uninspiring surroundings. His singing was considered to be 'old-fashioned', even in the circa-1900 era. Consequently, his discs provide a retrospective guide to Italian singing practice of the early-to-mid-19th century (the era of Gaetano Donizetti and Vincenzo Bellini)—as well as exemplifying the "grand manner" style of vocalism for which much Romantic operatic music was written. Battistini delivers this kind of music in a virile, bold and patrician way.

He is not averse, however, to showing off his voice by prolonging top notes or embellishing the written score with a liberality that might surprise 21st-century listeners who are imbued with the modern notion that a composer's work is sacrosanct. For some inexplicable reason he eschews on disc one of the key vocal ornaments at the disposal of all thoroughly schooled 19th-century bel canto singers: the trill.

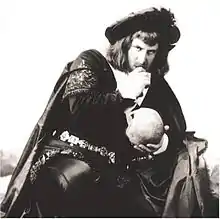

Perhaps Battistini's most historically illuminating recording is that of "Non mi ridestar", the Italian version of "Pourquoi me reveiller", a tenor aria from Massenet's Werther. Massenet transposed the protagonist's role downwards for baritone in a special version made especially for Battistini, harking back to an age when composers tailored their musical parts to fit the talents of one singer, and a singer of Battistini's stature could make almost any modifications seem acceptable. For those listeners sampling Battistini's discography for the first time, his touchstone recorded performances include versions of arias from Don Sebastiano, Macbeth, Don Carlos, Tannhäuser and L'Africana—plus a scintillating series of excerpts of Don Carlo's scenes from Ernani, arguably his greatest part, which he committed to wax in 1906. For an evaluation of Battistini's technique, style and legacy on disc, see his entry in Volume One of Michael Scott's survey The Record of Singing (published by Duckworth, London, 1977, ISBN 978-0-7156-1030-5).

Bibliography

Elsa Boscardini, of the Istituto Eugenio Cirese in Rieti, has published a number of pamphlets about Battistini, namely:

- Mattia Battistini, breve profilo storico-biografico (1980);

- L'arte di Mattia Battistini (1981);

- Mattia Battistini entusiasma le platee umbre (1993);

- Mattia Battistini, il favorito di Pietroburgo (1994);

- Mattia Battistini, interprete delle melodie di Donizetti (1998); plus

- Dolores Figueroa y Solís, la esposa de Mattia Battistini (written in Spanish and illustrated).

See also the following books:

Celletti, Rodolfo (1996): The History of Bel Canto. Oxford & London, Oxford University Press;

Celletti, Rodolfo (1964): Le grandi voci. Rome, Istituto per la collaborazione culturale;

Chuilon, Jacques (1996): Battistini Le Dernier Divo. Paris, Romillat, AND, an English-language edition of Chuilon's detailed book, translated by E. Thomas Glasow, with a new preface by Thomas Hampson, and including a CD with 19 titles, and numerous rare photos from Chuilon's private collection, namely, Chuilon, Jacques (April 2009): Mattia Battistini, King of Baritones and Baritone of Kings, Lanham, MD, USA, Scarecrow Press ;

Fracassini, G. (1914): Mattia Battistini. Milano, Barbini;

Karl Josef Kutsch and Leo Riemens, editors (2000): Großes Sängerlexikon Basel, Saur;

Lancellotti, A (1942): Le voci d' oro. Rome, Palombi;

Monaldi, G (1929): Cantanti Celebri. Rome, Tiber; and

Palmeggiani, Francesco (1977): Mattia Battistini, il re dei baritoni Milano, Stampa d' Oggi Editrice, 1949 (reprinted with discography, W.R. Moran, editor, New York, Arno Press).

References

- "Marston Records Liner Notes". Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Steane, J.B., 1998. Singers of the Century, vol. 2. Amadeus Press, Portland, pp. 48–52.

- Sarobe, Celestino (11 January 1936). "Conférence sur le chant". Lyrica (published April 1936): 2723–2726 – via Gallic.

- "Xirellis Titos - Greek National Opera". virtualmuseum.nationalopera.gr. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Mattia Battistini-The Complete Recordings". Archived from the original on 29 August 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.