Matthias Buchinger

Matthias Buchinger (German: [maˈtiːas ˈbʊxɪŋɐ]; June 2, 1674 – January 17, 1740), sometimes called Matthew Buckinger in English, was a German artist, magician, calligrapher, and performer who was born without hands or feet and was 2'5" (74 cm.) tall.[1] Buchinger was especially noted for his micrography, in which illustrations consist of very small text.[2]

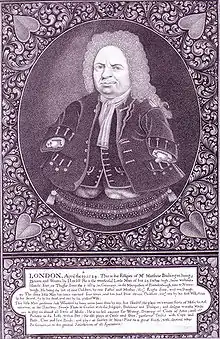

Matthias Buchinger | |

|---|---|

Self portrait | |

| Born | June 2, 1674 |

| Died | January 17, 1740 (aged 65) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation | Artist, magician, calligrapher |

Biography

Buchinger was born in Ansbach, Germany, without hands or lower legs. An artist and performer, he "traveled all over Northern Europe to entertain kings and aristocrats as well as hoi polloi with amazing feats of physical dexterity" and was known as “The Greatest German Living” and "Little Man from Nuremberg".[2][3] He travelled to England trying to get a court appointment with King George I; unsuccessful, he then moved to Ireland where he gave public demonstrations, in Dublin in 1720 and in Belfast in 1722. Buchinger was married four times and had at least 14 children (by eight women). He also is rumored to have had children by as many as 70 mistresses.[4][5] Buchinger's fame was so widespread that in the 1780s the term "Buckinger's boot" existed in England as a euphemism for the vagina (because the only "limb" he had was his penis).[6] Buchinger died in Cork, Ireland.

Despite his having small, finlike appendages for hands, his engravings were incredibly detailed. One such engraving, a self-portrait, was so detailed that a close examination of the curls of his hair revealed that they were in fact seven biblical psalms and the Lord's Prayer, inscribed in miniature letters.[4]

Despite his handicap Buchinger was an accomplished magician, causing balls to disappear from under cups and birds to appear from nowhere. It also was said that he was unbeatable at cards and would dazzle audiences with his amazing displays of marksmanship. Buchinger liked to build ships in a bottle. He had tremendous dexterity, in spite of his disability.[7]

Buchinger's musical skills included the ability to play a half-dozen musical instruments including the dulcimer, hautboy, trumpet, and flute and several of his own invention.[5]

Legacy

The Metropolitan Museum of Art presented 16 of his graphic works in a historical show entitled, “Wordplay: Matthias Buchinger’s Drawings From the Collection of Ricky Jay”.[8] Jay, a magician "collector of antique marvels", tracked down Buchinger's works for more than 30 years. He chronicled his pursuit of all things Buchinger in a book called Matthias Buchinger: ‘The Greatest German Living’ by Ricky Jay, Whose Peregrinations in Search of the ‘Little Man of Nuremberg’ Are Herein Revealed.[9]

See also

References

- "Matthew Buchinger". Dublin Penny Journal at the National Library of Ireland. April 27, 1833. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

- Ken Johnson (January 14, 2016). "Astounding Feats in Pen, Ink and Magnifying Glass".

- J. T. Penaud. "Human Marvels:Matthew Buchinger – The Little Man of Nuremberg". Retrieved March 18, 2011.

- Jackson, Holbrook (2001). The Anatomy of Bibliomania. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-07043-7.

Matthew Buchinger, who possessed neither hands nor legs, yet he married four times, ... the lines being composed of seven Psalms and the Lord's Prayer. ...

- Jay, Ricky (June 1, 2009). "Desperately Seeking Susan". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-06-03.

Buchinger demonstrated his skill on more than a half-dozen musical instruments (some of his own invention), danced a hornpipe, and performed conjuring tricks with cups and balls, cards and dice. In front of the lord provost he fashioned a pen and with it produced a fine calligraphic document of the coat of arms of the city. The year was 1726. Buchinger was 52 years old, 29 inches tall — and, he had neither legs nor arms. ...

- Grose, Francis (1785). The Vulgar Tongue.

- Kraven, Vlad. "Time Travel Part 1: Matthew Buchinger". Magician. Archived from the original on 1 September 2011. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

- Schjeldahl, Peter, Seeing and Believing: the mysteries of Matthias Buchinger, The New Yorker, January 25, 2016

- Peter Schjeldahl (January 25, 2016). "Seeing and Believing: The Mysteries of Matthias Buchinger". The New Yorker.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Matthias Buchinger. |

- Randi, James. Conjuring. (1992) ISBN 0-312-09771-9

- Blaine, David. Mysterious Stranger. (2002) ISBN 0-7522-1989-8