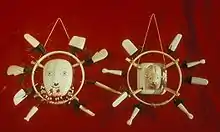

Masks among Eskimo peoples

Masks among Eskimo peoples served a variety of functions. Masks were made out of driftwood, animal skins, bones and feathers. They were often painted using bright colors. There are archeological miniature maskettes made of walrus ivory, dating from early Paleo-Eskimo and from early Dorset culture period.[2]

Despite some similarities in the cultures of the Eskimo peoples,[3][4][5][6][7] their cultural diversity[8] makes it hard to generalize how Eskimos and Inuit used masks. The sustenance, mythology, soul concepts, even the language[9] of the different communities were often very different.

Early masks

Archeological masks have been found from early Paleo-Eskimo and from early Dorset culture period.[2] It is believed that these masks served several functions, including being in rituals representing animals in personalized form;[10] being used by shaman in ceremonies relating to spirits (as in the case of a wooden mask from southwestern Alaska);[11] it is also suggested that they could be worn during song contest ceremonials.[12]

Associated beliefs

Although beliefs about unity between human and animal did not extend to that of absolute interchangeability,[13] several Eskimo peoples had sophisticated soul concepts (including variants of soul dualism) that linked living humans, their ancestors, and their prey.[14][15] Besides synchronous beliefs, there were also notions of unity between human and animal, and myths about an ancient time when the animal could take on human form at will.[10][16] Traditional transformation masks reflected this unity.[17] Ritual ceremonies could enable the community to enact these stories with the help of masks, sometimes with the masked person representing the animal.

Yup'ik masks

The Yup'ik people are Eskimos of Western Alaska whose masks vary enormously but are characterised by great invention. They differ in size from forehead and finger 'maskettes', to enormous constructions that dancers need external supports to perform with.[18] Many of these masks were used almost as stage props, some of which imbued the dancer with the spirit that they represented - and most were often destroyed after use. Others represented animal people, (yuit), and insects, berries, plants, ice and objects of everyday life.[18]

Note

Eskimo groups comprise a huge area stretching from Siberia through Alaska and Northern Canada (including Nunatsiavut in Labrador and Nunavik in Quebec) to Greenland. The term Eskimo has fallen out of favour in Canada and Greenland, where it is considered pejorative and the term Inuit has become more common. However, Eskimo is still considered acceptable among Alaska Natives of Yupik and Inupiat (Inuit) heritage, and is preferred over Inuit as a collective reference.

References

- Fienup-Riordan 1994: 206

- Hessel & Hessel 1998: 12–13

- Kleivan 1985:8

- Rasmussen 1965:366 (ch. XXIII)

- Rasmussen 1965:166 (ch. XIII)

- Rasmussen 1965:110 (ch. VIII)

- Mauss 1979

- Kleivan 1985:26

- Lawrence Kaplan: Comparative Yupik and Inuit Archived 2008-03-06 at the Wayback Machine (found on the site of Alaska Native Language Center Archived 2009-01-23 at the Wayback Machine)

- Oosten 1997: 90–91

- Burch & Forman 1988: 90–91

- Burch & Forman 1988: 30–31

- Oosten 1997: 99

- Oosten 1997: 86

- Vitebsky 1996:14

- Barüske 1969: 7, 9

- Thomas 2008 Archived 2008-05-09 at the Wayback Machine: +4 (= third page after the opening page of the article)

- The Living Tradition of Yup'ik Masks; Ann Feinup-Riordan; University of Washington Press, Seattle 1996. ISBN 0-295-97501-6

Further reading

- Barüske, Heinz (1969). "Wie das Leben entstand". Eskimo Märchen. Die Märchen der Weltliteratur (in German). Düsseldorf • Köln: Eugen Diederichs Verlag. pp. 6–13. The tale title means: "The way life appeared"; the book title means: "Eskimo tales"; the series means: "The tales of world literature".

- Burch, Ernest S. (junior); Forman, Werner (1988). The Eskimos. Norman, Oklahoma 73018, USA: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-2126-2.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Fienup-Riordan, Ann (1994). Boundaries and Passages: Rule and Ritual in Yup'ik Eskimo Oral Tradition. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Hessel, Ingo; Hessel, Dieter (1998). Inuit Art. An introduction. foreword by George Swinton. 46 Bloomsbury Street, London WCIB 3QQ: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-2545-8.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Kleivan, Inge; B. Sonne (1985). Eskimos: Greenland and Canada. Iconography of religions, section VIII, "Arctic Peoples", fascicle 2. Leiden, The Netherlands: Institute of Religious Iconography • State University Groningen. E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-07160-1.

- Mauss, Marcel (1979) [c1950]. Seasonal variations of the Eskimo: a study in social morphology. in collab. with Henri Beuchat; translated, with a foreword, by James J. Fox. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul. ISBN 0-415-33035-1.

- Oosten, Jarich G. (1997). "Cosmological Cycles and the Constituents of the Person". In S. A. Mousalimas (ed.). Arctic Ecology and Identity. ISTOR Books 8. Budapest • Los Angeles: Akadémiai Kiadó • International Society for Trans-Oceanic Research. pp. 85–101. ISBN 963-05-6629-X.

- Thomas, Lesley (2008). "Visions of the End of Days. Eskimo Shamanism in Northwest Alaska" (PDF). Sacred Hoop Magazine (59). ISSN 1364-2219. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- Vitebsky, Piers (1996). A sámán. Bölcsesség • hit • mítosz (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyar Könyvklub • Helikon Kiadó. ISBN 963-208-361-X. Translation of the original: The Shaman (Living Wisdom). Duncan Baird. 1995.