Marco Dente

Marco Dente da Ravenna (1493–1527), usually just called Marco Dente, was an Italian engraver born in Ravenna in the latter part of the 15th Century. He was a prominent figure within the circle of printmakers around Marcantonio Raimondi in Rome,[1] and is known for the imitative nature of his works that characterize his career. His prints in specific cases are also of certain interest in that we can see the impact and design of sculptural restorations.[2] Marco Dente was killed In the tumult of the Sack of Rome in 1527. He used the accompanying monogram, D-B; albeit sparingly.[3]

Early life and career

The artist was a member of a patrician family who grew up and lived in Ravenna for the majority of his life. He was an integral member of Marcantonio Raimondi's school of art, joining in 1516; Dente was likely an apprentice alongside Agostino di Musi, another Italian engraver.[2] Dente and Agostino di Musi formed the first generation of Marcantonio's school. However, between the two artists, Dente was considered to have come closest to mastering the technique of engraving.[1]

The characteristic that defines Marco Dente's work is the reproductive nature of his works. The reproductive nature of Dente's work served three functions. The first was to replicate an event in history; the second was to advance financially; the third was to produce with an intent to distribute the print, and as an extension, the print's conceptual elements too.[4] There was a growing demand for depictions of antique relief in the middle of the sixteenth century.[4] The school's commercial function was facilitated by the markets within La Bottega del Cartolaio; this is largely where prints by Marcantonio and Marco Dente were able to be exchanged or acquired.[5]

Works

Marco Dente's most notable work is his depiction of the Laocoön and his two sons. However, the majority of his known pieces like his depiction of The Massacre of the innocents, and The Judgement of Paris, are all reproductive in nature. Dente and the other members of Raimondi's school were specifically influenced by the works of Raphael. The workshop frequently used preliminary drawings from Raphael's studio to inform its practice, his studies of the city's archaeological remains were specifically influential. Both Raphael and Dente had 'mutual interests in the ruins of Rome'[6] - mirroring the general trend of Roman and the Greek classical antiquity becoming more influential throughout the Renaissance.

Laocoon

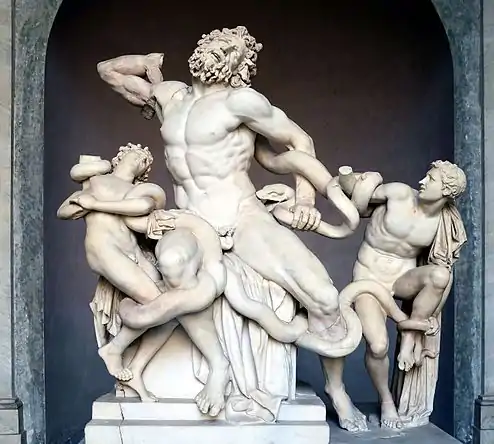

One of the most notable of Dente's pieces, and the one which seems to define the relatively unknown printmaker, is his version of the Laocoon. (Fig. 1) The Laocoon is described in Virgil's passage in The Aeneid. This print by Dente is significant in that it was engraved just after he witnessed the excavation of an ancient statue of the same subject in 1506.[7] Dente was heavily influenced by classical antiquity. His pieces Hercules and Antaeus, and Entellus and Dares, also depict figures based on ancient sculptures.[8] The sculpture of Laocoon and His Sons that was uncovered (Fig. 2) served as the foundation for Dente's subsequent print. Dente's print contributed to establishing a genre of reproductive engravings in the Renaissance depicting antiquity.[6]

The Laocoon is the only plate on which the engraver inscribed his name, 'Mrcus Ravenas'. Adolfo Venturi, an Italian art historian has argued Dente's print was based on a lost Raphael drawing. The link suggesting Raphael's influence is clear.[6] Dente's effort to reintegrate the sculpture with the ruins of Ancient Rome is a commentary on the restoration of Rome that was likely dictated by Raphael himself.[6] Dente's engraving of the Laocoon was completed before the restorations occurred on the excavated sculpture in 1530.[9] It is the discrepancy in Dente's depiction of a complete sculpture, and the fact restorations occurred on the sculpture after Dente's death, that links Raphael, whose long-standing involvement with the Laocoon is known, to co-operating with regard to ideas for this specific plate.[6] The engraving attempts to combine the narrative and visual aspects of the Laocoon.[8] Dente was also a member of Raphael's social circle.[10]

Raphael's involvement with the conceptual production of the plate is further corroborated by the fact that Il Baviera, Raphael's publisher, retained Marco Dente's plate for the Laocoon - evidence that Dente's print, or the design for it, belonged to Raphael. The piece was not like other works executed by Raimondi's School, which were usually copies of other artists' preliminary drawings for paintings or frescoes. This piece was intentionally created to be distributed through the medium of print.[6]

The engraving attempts to illustrate a glimpse of the history of the subject, but also convey Raphael's commentary on the restorations of antiquity.[6] In Dente's print of the Laocoon and his Sons, he uses the 'R S' monogram to record a different version of the fate of the Trojan priest.[7] Raphael wanted to see Rome restored to its former glory. The piece seeks to 'harmonize the Plinian sculpture with the Virgilian narrative'. Evidenced by the inscription of an excerpt from Book II of the Aeneid, and the inscription of text from Pliny's Natural History.[6] The evidence of Rome is seen through architectural structures and fragments; the depiction of an obelisk, as well as the style of the temple on the hill is equally iconically Roman.

Two of Dente's other famous works are his 'Battle of the Innocents', produced from a piece of the same title by Baccio Bandinelli, and his 'Judgment of Paris', an engraving he imitated from a piece completed by Marcantonio, who had based his after Raphael.

Imitation in Works

Marco Dente's skill as an imitator was clear. The artist is said to have 'forged so precisely' in so many of his prints.[5] It is common to see evidence of Dente's precision through his replication of arduously minute details of the master copy. Michael Bryan, in his Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, portrays Dente as a professional forger, with deceptive intents of his imitation.[3] This portrayal has merit. Many of Dente's works were copied line by line; others have inscriptions and signatures that directly correspond to originals by Marcantonio.

However, the artist's dedication to accuracy in his reproductive method had a purpose. It was not to deceive the buyer, who could be fooled with less effort; it also was not to deceive Marcantonio, who as an experienced engraver, would have been able to identify it is a forgery regardless of Dente's efforts. Il Baviera was the keeper of all the original plates made by Marcantonio and his colleagues; the accuracy of Dente's imitation was fore mostly intended to mislead Il Baviera, the keeper of the original plates. The marketing of Dente's works as masterpieces by Il Baviera would have meant both Dente and Baviera would have profited from the forgery.[5]

Anonymity

Marco Dente is not a well-known figure in the Renaissance. The reproductive nature of his works contributed to the subversion of his identity. There was much debate surrounding the attribution of artists within Marcantonio Raimondi's School, and their respective plates. Also contributing to the subversion of his identity was that every plate in Dente's studio was destroyed during the Sack of Rome. Marco Dente was killed in the same war; and very few of his plates were later reissued by publishers.[5]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marco Dente. |

- McG., K. W. (1919). Prints by Old Masters. Bulletin of the Art Institute of Chicago. pp. 103–106.

- Hind, Arthur M. (1963). A History of Engraving & Etching from the 15th Century to the year 1914. Dover Publications. p. 97.

- Bryan, Michael (1903). Dictionary of Painters and Engravers, Biographical and Critical. Macmillan. p. 398.

- Bury, Michael (1996). Beatrizet and the 'reproduction' of antique relief sculpture. London: Print Quarterly Limited. p. 121.

- Landau, David (1994). The Renaissance print, 1470-1550. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 295, 131–142, 120–125.

- Viljoen, Madeleine (December 2001). "Raphael and the Restorative Power of Prints". Pint Quarterly. 18: 378–379, 380, 382, 384.

- Lord, Carla (Summer 1984). "Raphael, Marcantonio Raimondi, and Virgil". Notes in the History of Art. 3: 27.

- Viljoen, Madeleine (September 2004). "Prints and False Antiquities in the Age of Raphael". Print Quarterly. 21: 237.

- Fisher, Richard (1879). Catalogue of a Collection of Engravings, Etchings, and Woodcuts. J.C. Wilkins. pp. 58–60.

- Wright, David H. "The Vatica Vergil: A Masterpiece of Late Antique Art". Classical World: A Quarterly Journal on Antiquity. 89: 497.