Marburg speech

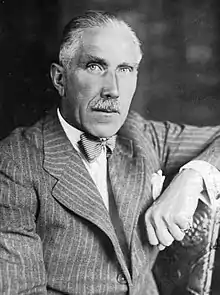

The Marburg speech (German: Marburger Rede) was an address given by German Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen at the University of Marburg on 17 June 1934.[1] It is said to be the last speech made publicly, and on a high level, in Germany against National Socialism. It was done in favour of the old nationalist-militarist clique that had run Germany in the Kaiser's time, who had helped Hitler to power as a prelude to their return, only to find themselves instead pushed aside by the New Order.

Papen, encouraged by President Paul von Hindenburg, spoke out publicly about the excesses of the Nazi regime, whose ascent to power, 17 months earlier when Adolf Hitler became chancellor of Germany, had been greatly assisted by him. In his speech, Papen called for an end to rule by terror and the clamouring for a "second revolution" by the Sturmabteilung (SA – the NSDAP's storm troopers), and the restoration of some measure of civil liberties. He also stated: "The government [must be] mindful of the old maxim 'only weaklings suffer no criticism'".

The speech was drafted by one of Papen's close advisors, Edgar Julius Jung, with assistance from Papen's secretary Herbert von Bose and Erich Klausener. It was delivered in an auditorium in the "Alte Universität," one of the main buildings in the university, but there is no plaque or any other form of commemoration of the Papen speech which, while historically labelled as Germany's last public speech against National Socialism, does not contain the term "Nazi", which the Nazis considered to be a pejorative.

Speech

… The events of the past one and one-half years have gripped the whole German people and affected them deeply. It seems almost like a dream that out of the valley of misery, hopelessness, hate, and fragmentation we have found our way back to a German national community. The horrendous tensions in which we have lived since the August days of 1914 have dissolved, and out of this discord, the German soul has emerged once again, before which the glorious and yet so painful history of our people pass in review, from the sagas of the German heroes to the trenches of Verdun, and even to the street fights of our time. An unknown soldier of the World War, who conquered the hearts of his countrymen with contagious energy and unshakable faith, has set this soul free. With his Field Marshal he has placed himself at the head of the nation, in order to turn a new page in the book of German destiny and to restore spiritual unity. We have experienced this unity of spirit in the exhilaration of a thousand rallies, flags, and celebrations of a nation that has rediscovered itself. But now, as the enthusiasm has lessened and tough work on this project has become imperative, it has become clear that a reform process of such historical proportions also produces slag, from which it must be cleaned. …

The function of the press should be to inform the government where deficiencies have crept in, where corruption has settled, where serious mistakes are being made, where unsuitable men are in the wrong positions, and where transgressions are committed against the spirit of the German revolution. An anonymous or secret news service, no matter how well organized, can never be a substitute for this responsibility of the press.…If other countries claim that freedom has died in Germany, then the openness of my remarks should instruct them that the German government can afford to allow a discussion of the burning questions of the nation. The only ones who have earned the right to enter this debate, however, are those who have put themselves at the service of National Socialism and its efforts without reservation and have proven their loyalty. …

If the liberal revolution of 1789 was the revolution of rationalism against religion, against attachment, so the counter-revolution taking place in the twentieth century can only be conservative, in the sense that it does not have a rationalizing and disintegrating effect, but once again places all of life under the natural law of Creation. That is presumably the reason why the cultural leader of the NSDAP, Alfred Rosenberg, spoke of a conservative revolution. From this there emerge in the field of politics the following clear conclusions: The time of emancipation of the lowest social orders against the higher orders is past. This is not a matter of holding down a social class – that would be reactionary – but of preventing a class from arising, gaining the power of the state, and asserting a claim to totality. Every natural and divine order must thereby be lost; it threatens a permanent revolution … The goal of the German Revolution, if it is to be a valid model for Europe, must therefore be the foundation of a natural social order that puts an end to the never-ending struggle for dominance. True dominance cannot be derived from one social order or class. The principle of popular sovereignty has, however, always culminated in class rule. Therefore, an anti-democratic revolution can only be consummated by breaking with the principle of popular sovereignty and returning to natural and divine rule. … But once a revolution has been completed, the government represents only the people as a whole, and is never the champion of individual groups; otherwise it would have to fail in forming a national community … It is not permissible, therefore, to dismiss the mind (Geist) with the catchword “intellectualism.” Deficient or primitive intellect are not in themselves justification for war against intellectualism. And if today we sometimes complain about 150 percent National Socialists, then we mean those intellectuals without substance, people who would like to deny the right of existence to scientists of world fame just because they are not Party members …

The sentence, “men make history,” has frequently been misunderstood as well. The Reich government is therefore right to criticize a false personality cult, which is the least Prussian kind of thing one can imagine. Great men are not made by propaganda, but rather grow through their deeds and are recognized by history. Even Byzantinism cannot delude us about the validity of these laws. Whoever speaks of Prussian tradition, therefore, should first of all think of silent and impersonal service, and last or not at all of reward and recognition. … I have so pointedly described the problems of the German Revolution and my attitude toward it, because talk of a second wave that will complete the revolution seems not to want to end. Whoever toys with such ideas should not conceal the fact that the one who threatens with the guillotine is the one who is most likely to come under the executioner’s axe. Nor is it apparent to what this second wave is to lead. Have we gone through an anti-Marxist revolution in order to carry out a Marxist program? …

No nation can afford a constant revolt from below if it wants to pass the test of history. The Movement must come to a standstill some day; at some time a stable social structure must emerge, maintained by an impartial judiciary and by an undisputed state authority. Nothing can be achieved through everlasting dynamics. Germany must not go adrift on uncharted seas toward unknown shores, with no one knowing when it will stop. History moves on its own; it is unnecessary to drive it on incessantly. If therefore the German revolution should experience a second wave of new life, then not as a social revolution, but as the creative culmination of work already begun. The statesman is there to create standards; the state and the people are his only concerns. The state is the sole power and the last guarantor of something to which every citizen can lay claim: iron-clad justice. Therefore, the state also cannot endure any dualism in the long term, and the success of the German Revolution and the future of our nation depend on whether a satisfactory solution can be found to the dualism between party and state.

The Government is well informed on all the self-interest, lack of character, want of truth, unchivalrous conduct, and arrogance trying to rear its head under cover of the German Revolution. It is also not deceived about the fact that the rich store of confidence bestowed upon it by the German people is threatened. If one wishes a close proximity to and a close connection with the people, one must not underestimate the good sense of the people; one must return their confidence and not constantly want to tell them what to do. The German people know that their situation is serious; they feel the economic distress; they are perfectly aware of the defects of many laws conditioned by the emergency; they have a discerning feeling for violence and injustice; they smile at clumsy attempts to deceive them with false optimism. No organization and no propaganda, no matter how good, will in the long run be able to retain trust. I have therefore viewed the wave of propaganda against the so-called petty critics differently from many others. Confidence and readiness to cooperate cannot be won by incitement, especially of youth, nor by threats against helpless segments of the people, but only by discussion with the people with trust on both sides. The people know that great sacrifices are expected from them. They will bear them and follow the Führer with unwavering loyalty, if they are allowed to have their part in the planning and in the work, if every word of criticism is not taken for ill will, and if despairing patriots are not branded as enemies of the state. …"[2]

Reaction

The speech made Hitler furious, and on Hitler's orders, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels attempted to suppress it. However, parts of it were printed in the Frankfurter Zeitung, narrowly avoiding the increasingly invasive censorship by the government. Also, copies of the speech were circulated freely within Germany and to the foreign press.[3] Papen was angered by this action from a "junior minister," and insisted he had spoken as a "trustee" of President Hindenburg. He submitted his resignation, and notified Hitler that he would inform Hindenburg at once. When Hindenburg learned of this, he was so outraged that he gave Hitler an ultimatum—unless Hitler acted immediately to end the disorder in Germany, he would sack Hitler and hand the government to the army.

Two weeks later, on the Night of the Long Knives, the SS and Gestapo murdered Hitler's enemies within the NSDAP, as well as various past friends and associates to whom his relationship might prove awkward, and several conservative opponents of the NS regime. During this blood purge Jung, von Bose, and Klausener were also murdered. Papen's office was ransacked and he himself held under house arrest but his life was spared. After the purge, Hitler formally accepted Papen's resignation as Vice Chancellor. Papen subsequently served as ambassador to Austria, and later served as ambassador to Turkey during the war, but played no further political role. In spite of his proximity to the anti-Hitler resistance of later years, he had no part in the 20 July plot to overthrow Hitler and the National Socialist government.

During the Nuremberg Trials, Papen, who was one of the main defendants, cited the Marburg speech as evidence of his distance from the excesses of the Nazi government of the time. The speech was later mentioned in the judgements of the Nuremberg trials, at which Papen was acquitted.

Literature

- "Rede des Vizekanzlers von Papen vor dem Universitätsbund, Marburg, am 17. Juni 1934", in: Edmund Forschbach: Edgar J. Jung. Ein konservativer Revolutionär 30. Juni 1934, 1984, p. 154ff.

- "Rede des Vizekanzlers von Papen vor dem Universitätsbund, Marburg, am 17. Juni 1934", in: Sebastian Maaß: Die andere deutsche Revolution. Edgar Julius Jung und die metaphysischen Grundlagen der Konservativen Revolution, 2009, p. 134ff.

- "Vice-Chancellor Franz von Papen's Marburg Speech: A Call for More Freedom, June 17, 1934" (English-language translation), in: Louis L. Snyder, editor: Hitler's Third Reich; A Documentary History, Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1981. pp. 173–177.

- "The Nazi Germany Sourcebook: AN ANTHOLOGY OF TEXTS" by Roderick Stackelberg & Sally A. Winkle

External links

- German text of the Marburg speech (in German)

References

- Anton Gill; An Honourable Defeat; A History of the German Resistance to Hitler; Heinemann; London; 1994; p.xiv

- Trial of the Major War Criminals Before the International Military Tribunal, Volume 15. International Military Tribunal. 1949. pp. 544–557.

- Kershaw, Ian (1998). Hitler, 1889-1936: Hubris. New York: Norton & Company Ltd. pp. 509–510.