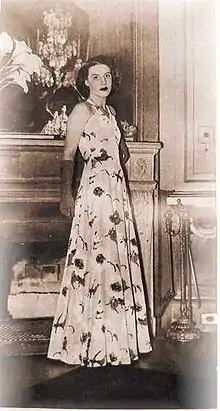

María Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat

María Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat (August 15, 1921 – February 18, 2012) was an Argentine executive and philanthropist.

María Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 August 1921 |

| Died | 18 February 2012 (aged 90) Buenos Aires |

| Occupation | Art collector and Businessperson |

| Net worth | |

| Spouse(s) | Hernán de Lafuente (1942–43) Alfredo Fortabat (1947–76) |

| Children | Inés de Lafuente |

Life and times

María Amalia Sara Lacroze Reyes de Fortabat Pourtal was born in 1921 to Amalia Reyes and Daniel Lacroze, members of prominent Argentine families; a grandfather, Federico Lacroze, developed Buenos Aires' first tramway line, in the 1880s. Her mother’s family descended from Uruguay’s second president, Manuel Oribe.[1] She was raised in Paris and in 1942, having returned to Argentina, married Hernán de Lafuente, with whom she had a daughter, María Inés. The marriage, however, ended in separation in 1943.[2][3]

Amalia (as she was known) had met Alfredo Fortabat, a divorced industrialist, during a Teatro Colón function, and the two began a relationship. Planning to wed, they were impeded by Argentina's then-conservative nuptial laws, which precluded separated couples from remarrying. The marriage, which ultimately took place in neighboring Uruguay in 1947, became recognized in Argentina following a reform signed into law by President Juan Perón, in 1951. The two enjoyed a close marriage, and Mrs. Fortabat's gregariousness and knowledge of four foreign languages made her a timely traveling companion in the industrialist's frequent business trips abroad; the marriage did suffer from a number of publicized infidelities, however.[3]

Founded by Alfredo Fortabat in 1926, Loma Negra became the leader in cement and concrete production in Argentina during the 1950s and '60s.[4] The death of her husband in 1976 left Mrs. Fortabat as the company's nearly sole owner, President and Chairperson.

Loma Negra enhanced its market leadership position in subsequent years by the opening of important new facilities and the acquisition of a chief competitor, Cementos San Martín S.A.[4] The business was enhanced further by her purchase of 65% in Ferrosur Roca, a state-owned freight and passenger railway that became Loma Negra's in-house transport service when Economic Minister Domingo Cavallo had it privatized in 1992.[5] That year, Fortabat broke ground on the group's new headquarters in the Catalinas Norte office park, in downtown Buenos Aires.[4]

Complications from debts of US$270 million stemming from a national economic crisis around 2001 were reportedly compounded by Mrs. Fortabat's choice of her eldest grandson, Alejandro Bengolea, as Director in 2000. Bengolea was dismissed in 2002, and her own advanced age prompted the grande dame of Argentine industry to sell her 80% stake in Loma Negra. The company was thus transferred to Brazilian conglomerate Camargo Correa in May 2005, for just over US$1 billion.[5]

Mrs. Fortabat, whose estimated net worth of US$2 billion made her Argentina's wealthiest woman,[5] served as Chairperson of Loma Negra Compania Industrial Argentina S.A., and was a Member of the Latin American Advisory Board of Deutsche Bank AG since January 2008.[6] The owner of various, valuable Buenos Aires properties, as well as 40 estancias totaling 160,000 hectares (395,000 acres), she sold her Manhattan penthouse atop the Pierre Hotel in 2011 for nearly US$20 million.[7]

Mrs. Fortabat's health had declined amid worsening respiratory problems. She died in her Avenida del Libertador home in Buenos Aires on February 18, 2012, at age 90.[8] She was interred in La Recoleta Cemetery.[9]

Political activities

After giving her support to the Peronist political movement of President-elect Carlos Saul Menem, Fortabat complained in 1989 that a major failing of Raul Alfonsin had been his lapse into "cronyism."[10] She cultivated a strong relationship with Menem, who later appointed her as a plenipotentiary ambassador, a privilege later revoked by Néstor Kirchner upon her sale of her 80% stake in Loma Negra to Brazilian conglomerate Camargo Corrêa in 2005.

Art collecting and philanthropy

As a patron of the arts, Mrs. Fortabat amassed an art collection reportedly valued at US$280 million (in 1999).[3] Mrs. Fortabat paid $6.4 million in 1980 for J. M. W. Turner’s painting Juliet and Her Nurse (1836) from the collection of Flora Payne Whitney, at the time a record price for a painting sold at auction.[11] Later, she sold many paintings, such as the Degas pastel Mary Cassatt at the Louvre (circa 1879), auctioned for $16.5 million at Sotheby's, New York, in 2002.[12]

Appointed President of the Fondo Nacional de las Bellas Artes (National Fine Arts Fund) in 1992,[2] she purchased a Puerto Madero lot in 1998 for the purpose of creating an art museum (including most of her collection).[5] The Fortabat Art Collection, a modernist museum in Buenos Aires designed by Rafael Viñoly, was inaugurated in October 2008.[13] As a philanthropist, she established the Fundación Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat (previously named Fundación Alfredo Fortabat y Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat), which has given more than $40 million to numerous charitable organizations throughout Argentina since 1976.[6] Among other causes, she gave many millions to the veterans of Argentina’s war with England over the Falkland Islands and refugees from the war in Kosovo in 1999.[11] Also, she was among the founders of the Fundación Teatro Colón, trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, and a major benefactor of the Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, the Museo Nacional de Arte Decorativo, the Mozarteum Argentino and the Museo de Arte Moderno de Buenos Aires.

In 1997, when a jury of the Fortabat Foundation decided to give its prize for the best first novel by an Argentine to “The Anatomist”, a controversial novel by Federico Andahazi, Fortabat did not approve. She bought a newspaper ad saying the subject matter did not “contribute to the exaltation of the highest values of the human spirit.” In the end, she agreed to give Andahazi the $15,000 award that went with the prize but not the prize itself.[14]

References

- Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat, billionaire cement heiress and modern art patron, dies at 90 Washington Post, February 18, 2012.

- "Murió Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat". La Nación.

- Colín, Julia. "Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat." Actual (6/1/1999) (in Spanish) Archived 2009-06-12 at the Wayback Machine

- Loma Negra: historia (in Spanish) Archived 2009-08-01 at the Wayback Machine

- "Río Negro: La trama de la venta del grupo Fortabat {{in lang|es}}". Archived from the original on 2008-10-21. Retrieved 2009-07-09.

- BusinessWeek: Loma Negra

- "Amalia Fortabat y su refugio neoyorquino". La Nación.

- "Murió a los 90 años Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat". A24. Archived from the original on 2012-07-31.

- "Business tycoon Amalia Fortabat dies aged 90". Buenos Aires Herald. 18 February 2012.

- Shirley Christian (July 8, 1989), Argentine Departs, Democracy Hardly Bankrupt New York Times.

- Douglas Martin (February 21, 2012), Amalia de Fortabat, 90, Dies; Noted for Art and Scandal New York Times.

- Carol Vogel (May 9, 2002), Art Sales Bring Strong Prices for a Second Night New York Times.

- Ñ: Un recorrido por el museo Fortabat (in Spanish)

- Calvin Sims (May 17, 1997), Sex and the Argentines: The Anatomy of a Scandal New York Times.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Amalia Lacroze de Fortabat. |

- MercoPress. One of Argentina’s wealthiest women dedicated to philanthropy and art buried in Buenos Aires

- Creating Emerging Markets Interview at the Harvard Business School