Mélanie Calvat

Françoise Mélanie Calvat (French: [fʁɑ̃swaz melani kalva], 7 November 1831 – 14 December 1904), called Mathieu, was a French Roman Catholic nun and Marian visionary. As a religious, she was called Sister Mary of the Cross. She and Maximin Giraud were the two Marian visionaries of Our Lady of La Salette.

Mélanie Calvat | |

|---|---|

Mélanie Calvat, 1903, Moulins, France. | |

| Born | 7 November 1831 |

| Died | 15 December 1904 (aged 73) |

| Resting place | Istituto Figlie del Divino Zelo via Annibale M. di Francia, 25 – Altamura, Italy 40.823054°N 16.556660°E |

| Nationality | French |

| Other names | Sister Mary of the Cross |

| Occupation | Roman Catholic Nun |

| Known for | Visionary of Our Lady of La Salette |

Biography

Early age

Calvat was born on 7 November 1831 in Corps en Isère, France. She was the fourth of ten children to Pierre Calvat, a stonemason and "pitsawyer by trade" who did not hesitate to take whatever job he could find in order to support his family, and Julie Barnaud, his wife. The family was so poor "that the young were sometimes dispatched to beg on the street".[1]

At a very young age, Calvat was hired out to tend the neighbors' cows, where she met Maximin Giraud on the eve of their apparition. From the spring to the fall of 1846 she worked for Jean-Baptiste Pra at Les Ablandins, one of the hamlets of the village of La Salette. She only spoke the regional Occitan[2] dialect and fragmented French. She had neither schooling nor religious instruction, thus she could neither read or write.

Apparition

On 19 September 1846, it is related that Calvat and Maximin Giraud – who at that time were just teenagers – saw an apparition of the Virgin Mary in the mountains of La Salette. The apparition transmitted both a public message to them, and a personal message to each of them.[3]

The bishop of Grenoble, Philibert de Bruillard, named several commissions to examine the facts. In December 1846, the first commissions were established. One was formed of professors from the major seminary of Grenoble and the other from titulary canons. The latter commission concluded that a more extensive examination was necessary before formulating a judgment. A new inquiry was held from July to September 1847, by two members of the commission, Canon Orcel, the superior of the major seminary, and Canon Rousselot.[4]

A conference on the matter at the bishop's residence took place in November–December 1847. Sixteen members – the vicars general of the diocese, the parish priests of Grenoble and the titulary canons – assembled in the presence of the bishop. The majority concluded to the authenticity of the apparition, after the examination of the report from Rousselot and Urcel. Moreover, the Bishop of Sens had examined very carefully three cures attributed to Our Lady of La Salette that had occurred in the city of Avallon. The local bishop, Mgr. Mellon Jolly, recognized on 4 May 1849, one of the three cures, which had occurred on 21 November 1847, as miraculous.

Mgr. de Bruillard was convinced of the reality of the apparition and authorized the publication of the Rousselot report, which affirmed the reality of the apparition. In his letter of approbation, added as a preface, the bishop of Grenoble declared that he shared the opinion of the majority of the commission which adopted the conclusions of the report.

However, Louis Jacques Maurice de Bonald, the Cardinal Archbishop of Lyon, on whom Grenoble depended, suspected a subterfuge. The Cardinal demanded that the children tell him their secret, saying that he had a mandate from the Pope. The children finally acceded to this demand. Calvat, however, insisted that her text be carried directly to the Pope. It was under these conditions that the Bishop of Grenoble sent two representatives to Rome. The text of the two private secrets were reportedly handed to Pope Pius IX on 18 July 1851, but apparently subsequently lost.

The procedure was favourable, since the mandate of Mgr. de Bruillard, adjusted according to observations of Luigi Lambruschini, Cardinal Prefect of the Sacred Congregation of Rites at Rome, was signed on 18 September 1851, and was published the following 10 November 1851. In it, the bishop of Grenoble promulgated this judgement: "We judge that the apparition of the Holy Virgin to the two shepherds, 19 September 1846 ... in the parish of La Salette ... carries within it all the characteristics of truth, and that the faithful have reason to believe it indubitable and certain."[5]

The motives of the decision, which rested on the work of Rousselot and that of the commission of 1847, were the impossibility of explaining the events, the miracles and the cures in a human manner, as well as the spiritual fruits of the apparition, notably conversions and finally the right expectations and desires of large crowds of priests and faithful.

Later, 16 November 1851, the Bishop of Grenoble published a statement that the mission of the shepherd children had ended and that the matter was now in the hands of the Church. The bishop made it clear that the approval of the Church was only for the original revelation of 1846 and not for any subsequent claims.

La Salette immediately stirred up a great fervour in French society, it also provoked enormous discussions. The little visionaries were somewhat disturbed by the perpetual interrogations, the threats, sometimes violent from political and ecclesiastical opponents, and also the assaults of fervour. Calvat especially was venerated in the manner of a saint, not unlike what happened to Saint Bernadette Soubirous, who, without doubting, defended herself against this. This harmed the equilibrium of the two visionaries. Calvat had difficulty living a stable religious life. Maximin, who entered the seminary, also had difficulties living a normal life.

Religious life

After the apparition in 1846, Calvat was placed as a boarder in the Sisters of Providence Convent in Corenc close to Grenoble. "As early as November 1847, her directress feared 'that the celebrity that had been thrust upon her might make her conceited'."[1] She entered religion at the age of twenty and in 1850 she became a postulant with this order and in October 1851 she took the veil. While at Corenc she was known to sit down surrounded by enthralled listeners, as she related stories of her childhood.

In May 1853, Bishop de Bruillard died. In early 1854 his replacement refused to grant permission for her to be professed, because he found that she was not spiritually mature enough.[6] Calvat claimed that the real reason for the refusal was that the bishop was aiming to gain the favour of the emperor Napoleon III of France.

Following the bishop's refusal to permit her to be professed, Calvat was officially allowed to move to a convent of the Sisters of Charity. This order was dedicated to hard practical work in helping the poor, and Calvat met brisk common sense, not flattery or adulation. Calvat continued to speak about the apparitions, and a masonic plot to destroy Catholic France. But after three weeks she was returned to Corps en Isère for further education.

Napoleon III was ruling republican France but royalists were plotting to restore the king of the Catholic country. This political controversy dominated conversation throughout France, with the French church trying to maintain neutrality. Calvat made this difficult for the hierarchy, by continuing to repeat the reputed words of the Virgin Mary and opposing freemasonry. The bishop, aware of Melanie's fervid and outspoken royalist sympathies, was worried that she would become involved and thereby implicate the following of Our Lady of La Salette in politics. In 1854, Bishop Ginoulhiac wrote that the predictions attributed to Melanie had no basis in fact and had no importance with regard to La Salette as they came after La Salette and had nothing to do with it.

Calvat agreed to the suggestion of an English visiting priest, and was allowed to move to the Carmel at Darlington in England, where she arrived in 1855. This removed her from the French political controversies, so the bishop was pleased to agree to this move. She took temporary vows there in 1856. In 1858 Calvat wrote again to the Pope to transmit that part of the secret she was authorized to reveal in that year. While at Darlington she spoke of a variety of strange events and miracles. The local bishop forbade her to speak publicly about these prophecies. In 1860, she was released from her vow of cloister at the Carmel by the Pope[7] and returned to mainland Europe.

She entered the Congregation of the Sisters of Compassion in Marseille. A sister, Marie, was appointed as her companion. After a stay in their convent of Cephalonia, Greece where she and Sister Marie went to open an orphanage, and a short sojourn at the Carmelite convent of Marseille, she returned to the Sisters of Compassion for a brief period. In October 1864 she was admitted as a novice on condition she kept her identity secret. But she was recognized and her identity was no longer secret. In early 1867 she was officially released from the order and she and her companion then went, following a short stay at Corps and La Salette, to live at Castellamare[7] near Naples in Italy, where she was welcomed by the local bishop. She resided there seventeen years, writing down her secret, including the rule for a future religious foundation. Calvat visited the Sanctuary at La Salette for the last time on 18–19 September 1902.

Death

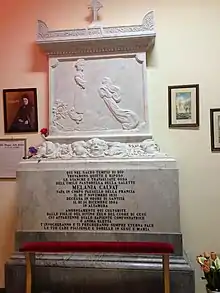

On 14 December 1904 Calvat was found dead in her home in Altamura, Italy.[1] Mélanie Calvat fled to Altamura, where she never revealed her identity. For the locals, she was just an old French woman who used to go every day to the cathedral for the mass. Her identity was revealed only after her death.[8]

Her remains are buried under a marble column with a bas-relief depicting the Virgin Mary welcoming the shepherdess of La Salette into heaven.

Controversy

In 1873 Mélanie Calvat wrote her personal message down again, with the imprimatur of Sisto Riario Sforza, Cardinal Archbishop of Naples. Meanwhile, religious orders were being formed at La Salette, under the auspices of the local bishop, of Grenoble. These were to provide for the pilgrims and spread the message of the vision. Mélanie Calvat claimed she had been authorized by apparition to provide the names of these orders, their rules and their habits. The one for men was to be entitled Order of the Apostles of the Last Days, the one for the women the Order of the Mother of God. When the bishop refused her demands, she appealed to the Pope and was granted an interview. Mélanie Calvat was received by Pope Leo XIII in a private audience on 3 December 1878.

The message was officially published by Mélanie Calvat herself on 15 November 1879 and received the imprimatur of Mgr. Salvatore Luigi Zola, bishop of Lecce near Naples (who had protected and assisted Calvat in his diocese) under the title Apparition of the Blessed Virgin on the Mountain of La Salette.[9] As a consequence of this publication, a historical dispute on the extent of the secret began, which lasts until today.

Calvat's anti-Masonic and apocalyptic pronouncements prompted a reaction. In 1880 the bishop of Troyes denounced the Lecce book to the Congregation of the Holy Office, and in turn Prospero Caterini, Cardinal Secretary of the Congregation of the Holy Office, wrote back to him, in August 1880 saying that the Holy Office was displeased with the publication of this book, and wished copies withdrawn from circulation. The letter was passed on to the Bishop of Nîmes, and later that autumn portions of it were published. It is not clear whether Caterini's letter was personal correspondence or represented an official condemnation.[7][10] The Vatican later put this book on the Index of Prohibited Books.[11]

Mélanie Calvat moved to Cannes in the south of France, from where she travelled to Chalon-sur-Saône, seeking to found a community with the sponsorship of the Canon de Brandt of Amiens. Eventually she entered into litigation with Bishop Perraud, the ordinary of Autun over an inheritance given to support this foundation.

In 1892, Mélanie Calvat returned to Lecce, Italy, then journeyed to Messina in Sicily at the invitation of Saint Annibale Maria di Francia. Following a few months in the Piedmont region, she was invited by the abbé Gilbert Combe, pastor of Diou, a priest much taken up with prophecies, to settle in the Allier region. She there finished her autobiography. In 1894 Combe published his version of Melanie's prohibited secret under the title The Great Coup and Its Probable Dates,[12] which was anti-Bonaparte and pro-Bourbon. It was reprinted at Lyon in 1904, a few months before Calvat's death. It too was put on the Index.[10]

"Melanists"

Calvat was manipulated by different groups of prophecy enthusiasts, some with political agendas. In 1847 self-proclaimed prophetess Therese Thiriet presented her message as "an addition to the prediction of the children of the district of Grenoble", largely against the Bishop of Nancy.[4] Melanie early began to blame the cabinet of Napoleon III for the evils she saw about to befall France, and viewed the Franco-Prussian War as a judgment from God.[7] Melanie's "prophetic meanderings" were later "orchestrated by […] Leon Bloy" and it became "a 'Melanist' movement allegedly stemming from La Salette, but lacking any foundation except the unverifiable pronouncements of Mélanie".[1] Inspired by both millennialist visionary Eugène Vintras and the reports of an apparition at La Salette, Bloy was convinced that the Virgin's message was that if people did not reform the endtime was imminent.[13] In 1912 Leon Bloy, an ardent millennialist, published a posthumous autobiography of Calvat, in which Melanie claimed to have had miraculous and prophetic experiences before the apparition of 1846.[11]

Jacques Maritain noted that "[T]here was a small number of fanatics who made the Secret of La Salette a partisan affair, and whose aberrant interpretations, and their manner of using prophecies like a railway timetable, could only compromise the cause which they claimed to defend.[14]

Legacy

Each apparition is particular to its own milieu and time. Kenneth Woodward has observed that "seers acquire charismatic authority, which is routinely challenged by institutional authority in the figure of the local bishop. ... The bishop is duty bound to take the part of the Devil's advocate, to simultaneously question the authenticity of the apparition and explore its possible meaning for the church."[15]

Once again, during the pontificate of Pope Benedict XV, the Church was compelled to address the issue. Benedict XV issued an admonitum or formal papal warning recognizing the many different versions of the secret in all its diverse forms and forbidding the faithful or the clergy to investigate or discuss them without permission from their bishops. The admonitum further affirmed that the Church's prohibition issued under Pope Leo XIII remained binding. A decree in 1923 was prompted by the reprinting of the 1879 edition subsequently altered by an anti-clerical partisan of the secret.

Since the Second Vatican Council, the rules regarding the discussion of visions have been relaxed and the Index abolished. Her book was republished, and discussion once again took place.

Beatification process

On reading an account of her life in 1910, Pope Pius X exclaimed to the Bishop of Altamura, in whose diocese she had died and was buried, "La nostra Santa!" He suggested to the Bishop that her cause for beatification be introduced immediately.[16] Despite this, Calvat is not currently beatified nor canonized by the Catholic Church.

Texts of the revealed secret

Both Melanie Calvat's and Maximin Giraud's accounts of the message of the "beautiful lady" agree. According to the two children's account, the Virgin invited people to respect the repose of Sunday, and the name of God, and cautioned punishment, in particular a scarcity of potatoes, which would rot. She also encouraged them to pray. Their respective "secrets" appear to differ in both content and tone. Maximin's is somewhat more hopeful.

Mélanie composed various versions of her secret throughout her life. It was noted that the 1879 brochure appeared to be longer than the letter sent to the Pope in 1851. Bishop Zola explained that Melanie had not revealed the entire secret at that time.[10] A lively controversy followed as to whether the secret published in 1879 was identical with that communicated to Pius IX in 1851, or in its second form it was not merely a work of the imagination. The latter was the opinion of wise and prudent persons, who were persuaded that a distinction must be made between the two Mélanies, between the innocent and simple visionary of 1846 and the visionary of 1879, whose mind had been disturbed by reading apocalyptic books and the lives of illuminati.[3] According to Fr. J. Stern, these later divulgations have nothing to do with the apparition, and Melanie carried to her grave the secret she received that day.[4]

- The original version was written down on 6 July 1851, at the behest of the Bishop of Grenoble.

If, when you say to the people what I have said to you so far, and what I will still ask you to say, if, after that, they do not convert, (if they do not do penance, and they do not cease working on Sunday, and if they continue to blaspheme the Holy Name of God), in a word, if the face of the earth does not change, God will be avenged against the people ungrateful and slave of the demon. ... Paris, this city soiled by all kinds of crimes, will perish infallibly. Marseilles will be destroyed in a little time. ...The pope will be persecuted from all sides, they will shoot at him, they will want to put him to death, but no one will not be able to do it, the Vicar of God will triumph again this time. ...The priests and the Sisters, and the true servants of my Son will be persecuted, and several will die for the faith of Jesus-Christ....A famine will reign at the same time. ...After all these will have arrived, many will recognize the hand of God on them, they will convert, and do penance for their sins. ...That time is not far away, twice 50 years will not go by.

- Second version – 5, 6, 12 and 14 August 1853: A new version was produced on request of Jacques-Marie-Achille Ginoulhiac, the new bishop of Grenoble, who was unacquainted with the secret.

- 1858: Calvat wrote to the Pope in 1858. As she was in Darlington at the time, it would have been forwarded through the English College in Rome. No copy has ever been located.

- 1860-1870-1873: The extended text of 1858 was reproduced in Marseille in 1860 on request of the superiors of Mélanie Calvat. A copy of the reproduction of 1860 was made in Castellammare in 1870 and was published on 30 April 1873 by Félicien Bliard, a French priest. This publication contained the approval of the archbishop of Naples, Sisto Cardinal Sforza.

- 1879: Calvat published a pamphlet about the apparitions. At this point anti-clerical views become apparent, which could have been influenced by her difficulties with the religious authorities. She was not permitted to pronounce religious vows in the diocese of Grenoble.[4] In this version Calvat also states that the Holy Virgin gave her the rule of a new religious order. Her predictions for 1859, 1864, and 1865 were first published in the 1879 version.

Melanie, what I am going to tell you now will not always be secret. You will be allowed to publish it in 1858. ... Woe to the priests and to persons consecrated to God, who by their infidelities and their bad life are crucifying anew my Son!The leaders, the guides of the people of God have neglected prayer and penance, ... God will permit the old serpent to place divisions among rulers, in all societies and in all families; physical and moral pains will be suffered; God will abandon men to themselves, and will send chastisements which will follow one after another for more than thirty-five years.

Society is on the eve of the most terrible scourges and of the greatest events; one must expect to be ruled with an iron rod and to drink the chalice of the wrath of God. (This part appealed to Bloy's views on redemptive suffering.) May the Vicar of my Son, the sovereign Pontiff Pius IX, no longer leave Rome after the year 1859; but may he be firm and generous, may he fight with the weapons of faith and love; I will be with him. May he be wary of Napoleon; his heart is double, and when he will want to be at the same time Pope and emperor, soon God will withdraw from him: he is this eagle who, wanting always to raise himself up, will fall on the sword which he wanted to use in order to force the peoples to raise him up.

Italy will be punished for her ambition in wanting to shake off the yoke of the Lord of Lords; also she will be delivered over to war. ...In the year 1864, Lucifer with a great number of demons will be unleashed from hell; they will abolish the faith little by little.

Bad books will abound on earth, and the spirits of darkness will spread everywhere a universal slackening in all that concerns the service of God; ...The dead and the just will be made to revive. [That is to say that these dead will take the appearance of just souls who had lived on earth, so as to better mislead men: these so-called resurrected dead, who will be nothing other than the demon under these appearances, will preach another Gospel contrary to the one of the true Christ Jesus, denying the existence of heaven, or they may also be the souls of the damned. All these souls will appear as if united to their bodies.]... Civil and ecclesiastical powers will be abolished, all order and all justice will be trampled underfoot; one will see only homicides, hatred, jealousy, lying and discord, without love for country, or for family.

In the year 1865, the abomination will be seen in holy places; in convents, the flowers of the Church will be decayed and the demon will make himself as the king of hearts. ...France, Italy, Spain and England will be in war; blood will flow in the streets; Frenchman will fight with Frenchman, Italian with Italian; subsequently there will be a general war which will be appalling. ...Paris will be burned and Marseilles engulfed; several great cities will be shaken and engulfed by earthquakes: it will be believed that all is lost: only homicides will be seen, only the noise of weapons and blasphemies will be heard. ... Then Jesus Christ by an act of His justice and of His great mercy for the just, will command to His angels that all His enemies be put to death. All at once the persecutors of the Church of Jesus Christ and all men devoted to sin will perish, and the earth will become like a desert. Then peace, the reconciliation of God with men will be made; ...The new kings will be the right arm of the holy Church, which will be strong, humble, pious, poor, zealous and imitator of the virtues of Jesus Christ.

This peace among men will not be long; 25 years of abundant harvests will make them forget that the sins of men are the cause of all the pains which come upon the earth. ...The earth will be struck all kinds of plagues [in addition to pestilence and famine which will be general;] there will be wars until the last war, which will then be made by the ten kings of the antichrist.

The seasons will be changed, the earth will produce only bad fruits, the stars will lose their regular movements, the moon will reflect only a feeble reddish light; water and fire will give to the globe of the earth convulsive movements and horrible earthquakes which will cause to be engulfed mountains, cities [etc.]. ... God will have care of His faithful servants and men of good will; the Gospel will be preached everywhere, all peoples and all nations will have knowledge of the truth! ... pagan Rome will disappear; fire from Heaven will fall and will consume three cities.[17]

- Combe version: published 1904.

The great chastisement will come, because men will not be converted; ...Penance is not done, and sin increases daily. In consequence of this, it is necessary that a very great and terrible scourge should come to revive our faith, and to restore to us our very reason, which we have almost entirely lost. Wicked men are devoured by a thirst for exercising their cruelty; but when they shall have reached the uttermost point of barbarity, God Himself shall extend His hand to stop them, and very soon after, a complete change shall be effected in all surviving persons. Then they will sing the Te Deum Laudamus with the most lively gratitude and love. The Virgin Mary, our Mother, shall be our liberatrix. Peace shall reign, and the charity of Jesus Christ shall unite all hearts....[18]

Combe incorporated Calvat's 1879 pamphlet into his own subsequent publication in support of his political views. It was placed on the Index. Again in 1906 another of Combe's publications titled The Secret of Melanie and the Current Crisis[19] was again placed on the Index. These actions of the Church caused some confusion as to whether just Combe's book or the secret itself was placed on the Index. In October 1912, Albert Lepidi O.P., Master of the Sacred Palace, replying to a query by cardinal Louis Luçon, affirmed that the original message of 1846 remained approved. The latter messages, and particularly the 1872–1873 version, were not.[10]

References

- The Children of La Salette, Missionaries of La Salette

- Bert and Costa (2010: 18).

- Clugnet, Léon. "La Salette." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 29 Dec.

- Marian Apparitions, University of Dayton

- Borrelli, Antonio. "Melania Seer of La Salette", Santi Beati, April 6, 2006

- Borelli, Antonio. "Melania", Santi e Beati, 6 April 2006

- St. John, Bernard, The Blessed Virgin in the Nineteenth Century: Apparitions, Revelations, Graces, p. 188, Burns & Oates, London, 1903

- "Altamura ricorda l'apparizione della Madonna de la Salette".

- Calvat, Mélanie (1879). L'Apparition de la très sainte vierge sur la montagne de la Salette le 19 septembre 1846, publiée par la bergère de la Salette avec imprimatur de l'Evéque de Lecce (in French). Lecce: Mélanie Calvat. (Méricourt-l'Abbé (Somme): Imprimerie Notre-Dame de la Salette, 1930: available at Gallica. Paris: Librairie Sainte-Geneviève, 1905: available at Gallica)

- Zimdars-Schwartz, Sandra L., Encountering Mary: From La Salette to Medjugorje, Princeton University Press, 2014 ISBN 9781400861637

- Wessinger, Catherine (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Millennialism. Oxford Handbooks. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 554. ISBN 978-0-19-990990-2.

- id:tL93YgEACAAJ, id:xUlqswEACAAJ, id:qzy0mAEACAAJ, id:uHY3RksqXGgC at Google Books

- Ziegler, Robert (October 2013). "The Palimpsest of Suffering: Léon Bloy's Le Désespéré". Neophilologus. 97 (4): 653–662. doi:10.1007/s11061-012-9337-x.

- "Maritain, Jacques. "Our First Trip to Rome", Notebooks, Jacques Maritain Center". Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 21 September 2014.

- Woodward, Kenneth L., "Going to See the Virgin Mary", New York Times, August 11, 1991

- "The Secret of La Salette". Archived from the original on 22 May 2006.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 September 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Internet History Sourcebooks".

- id:plau1seydM4C at Google Books

Bibliography

- Bert, Michael and James Costa. 2010. "Linguistic borders, language revitalization and the imagining of new regional entities", Borders and Identities (Newcastle upon Tyne, 8–9 January 2010), 18.

- Rousselot, Pierre Joseph, La verité sur l'événement de La Salette du 19 September 1846 ou rapport à Mgr l'évêque de Grenoblesur l'apparition de la Sainte Vierge à deux petits bergers sur la montagne de La Salette, canton de Corps (Isère), Baratier, Grenoble, 1848 (fr)

- Rousselot, Pierre Joseph, Nouveaux documents, Baratier, Grenoble, 1850 (fr)

- Rousselot, Pierre Joseph, Un nouveau Sanctuaire à Marie, ou Conclusion de l'affaire de La Salette, Baratier, Grenoble, 1853 (fr)

- Calvat, Mélanie, L'Apparition de la Très-Sainte Vierge sur la montagne de la Salette, le 19 septembre 1846, publiée par la bergère de la Salette avec permission de l'ordinaire, 1st edition, G. Spacciante, Lecce, 1879 (fr) html

- Calvat, Mélanie, L'Apparition de la Très-Sainte Vierge sur la montagne de la Salette, le 19 septembre 1846, publiée par la bergère de la Salette avec permission de l'ordinaire, 2nd edition, G. Spacciante, Lecce, 1885 (fr) html

- Calvat, Mélanie & Bloy, Léon, Vie de Mélanie, Bergère de la Salette, écrite par elle-mêle en 1900, son enfance (1831–1846), 1st edition, Mercure de France, Paris, 1918 (fr) pdf

- Gouin, Paul, Sister Mary of the Cross. Shepherdess of La Salette. Melanie Calvat, The 101 Foundation, Asbury-NJ, 1968 (en)

External links

- Works by or about Mélanie Calvat at Internet Archive

- Text of secret in English and original French with photos.

- Woodward, Kenneth L., "Going to See the Virgin Mary", New York Times, August 11, 1991

- Depliant Melanie Calvat

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mélanie Calvat. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |