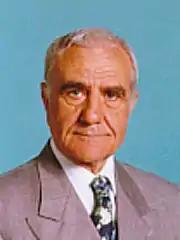

Ludovico Corrao

Ludovico Corrao (June 26, 1927 – August 7, 2011) was an Italian Independent Left politician and lawyer.

Ludovico Corrao | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 26 June 1927 |

| Died | 7 August 2011 (aged 84) |

| Occupation | lawyer, politician |

Biography

Professional activity

After his studies, first at the seminary and later at the law faculty, he practiced law; in 1965 he was Franca Viola’s plaintiff’s lawyer: she was the first woman in Italy who rose against the shotgun wedding and, by defying a male-dominated society, made a decisive contribution to have the honour crime deleted from Penal Code.[1]

Corrao also defended Graziano Verzotto who, according to Giuseppe Lo Bianco, was "the mysterious union man of E.N.I. with the power’s darkest environments in Sicily, already existing at the time of its president’s assassination, in the affair of slush funds of Ente Minerario, deposited in Michele Sindona's banks".[2]

Political activity with D.C. and Milazzismo

He started his political activity with the ACLI and the Christian Democracy; in 1955 he was elected as Deputy at ARS (Assemblea regionale siciliana), in the district of the province of Trapani for the list of DC.

In 1958 Corrao followed Silvio Milazzo in the political split from D.C. and became the regional minister for public works; he was one of theorists of Milazzismo. In 1959 he was re-elected in the list of Social Christian Sicilian Union, both in the district of Trapani and Palermo, and he was appointed a regional minister once again, alongside Silvio Milazzo in the two subsequent governments, first for Public Works and later for Industry and Commerce. From 1960 to 1962 he also was the Mayor of Alcamo and then he was only a town councillor.

Member of Parliament as independent leftist

After the end of Milazzismo, he approached to the Left; in 1963 he was elected a Member of Parliament at the Chamber of Deputies, as an independent in the list of PCI (Communist Party), in the Legislature IV of Italy, for the district of western Sicily. Since 1968 Corrao was elected Senator of the Republic in the Legislature V and VI of Italy, for the district of Alcamo, and joined the group of Independent Left until 1976.

He was elected again senator in 1994 and in 1996 (XII and XIII legislatures) with the list of PDS for the district of Alcamo until 2001. From 1995 to 2000 he was again the lord mayor of Gibellina. In 2001 The Olive Tree dropped him and he ran for the Senate of the Republic again (this time with Rifondazione Comunista), but was not elected.

Reconstruction of Gibellina and death

As lord mayor of Gibellina, after the Belice Earthquake, he called famous artists and architects, from Pietro Consagra to Alberto Burri, from Ludovico Quaroni to Franco Purini, who filled the new town with works of contemporary art; he was its lord mayor several times, until the 1980s.

His activity continued with the creation of Orestiadi di Gibellina in 1981 (a foundation since 1992, of which he was the president until death), and the Museo delle Trame Mediterranee, with the aim of realizing a dialogue among the different Mediterranean cultures.[1]

In 2005, the president of Regione Siciliana, Salvatore Cuffaro, entrusted him the management of Casa Sicilia in Tunis.

In 2010, together with the journalist Baldo Carollo, Corrao published Il sogno Mediterraneo, an interview-book which tells about sixty years of Sicily’s history,[3] reviewed by the intellectuals of that period Leonardo Sciascia, Carlo Levi, Pietro Consagra and Danilo Dolci: here Sicily is seen in the middle of a dialogue among different Mediterranean cultures, outside of any opposed fundamentalism.[3]

On 7 August 2011, Corrao, being 84 years old, was killed at Gibellina by Mohammed Saiful Islam, a 21-year-old Bengali working for him.[4]

References

Sources

External links

- "Ludovico Corrao: Una città non si ricostruisce con un disegno".

- Gibellina nuova, un museo a cielo aperto abbandonato a se stesso.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20170929044005/http://www.telesud3.com/fad/omaggio-a-ludovico-corrao

- http://www.trapaninostra.it/Foto_Trapanesi/Didascalie/Corrao_Ludovico.htm

- http://www.youreporter.it/video_Il_Sen_Ludovico_Corrao_sugli_ultimi_fatti_dell_Africa_1

- http://www.fondazioneorestiadi.it/it/notizie/312-omaggio-a-ludovico-corrao.html%5B%5D

- https://web.archive.org/web/20170929000812/http://www.creativelabalcamo.it/eventi/omaggio-a-ludovico-corrao/