Ludlow Castle

Ludlow Castle is a ruined medieval fortification in the town of the same name in the English county of Shropshire, standing on a promontory overlooking the River Teme. The castle was probably founded by Walter de Lacy after the Norman conquest and was one of the first stone castles to be built in England. During the civil war of the 12th century the castle changed hands several times between the de Lacys and rival claimants, and was further fortified with a Great Tower and a large outer bailey. In the mid-13th century, Ludlow was passed on to Geoffrey de Geneville who rebuilt part of the inner bailey, and the castle played a part in the Second Barons' War. Roger Mortimer acquired the castle in 1301, further extending the internal complex of buildings, and the Mortimer family went on to hold Ludlow for over a century.

| Ludlow Castle | |

|---|---|

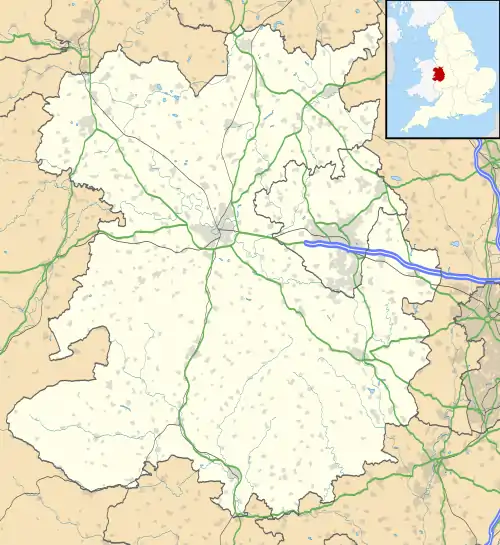

| Ludlow in Shropshire, England | |

Ludlow Castle from the south-east | |

Ludlow Castle | |

| Coordinates | 52.3672°N 2.7230°W |

| Grid reference | grid reference SO5086874594 |

| Site information | |

| Owner | The Earl of Powis and the Trustees of the Powis Estate |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruined |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1066–85 |

| Built by | Walter de Lacy |

| Materials | Siltstone and red sandstone |

| Events | The Anarchy, the Second Barons' War, the Wars of the Roses, the English Civil War |

Richard, the Duke of York, inherited the castle in 1425, and it became an important symbol of Yorkist authority during the Wars of the Roses. When Richard's son, Edward IV, seized the throne in 1461 it passed into the ownership of the Crown. Ludlow Castle was chosen as the seat of the Council in the Marches of Wales, effectively acting as the capital of Wales, and it was extensively renovated throughout the 16th century. By the 17th century the castle was luxuriously appointed, hosting cultural events such as the first performance of John Milton's masque Comus. Ludlow Castle was held by the Royalists during the English Civil War of the 1640s, until it was besieged and taken by a Parliamentarian army in 1646. The contents of the castle were sold off and a garrison was retained there for much of the interregnum.

With the Restoration of 1660, the Council was reestablished and the castle repaired, but Ludlow never recovered from the civil war years and when the Council was finally abolished in 1689 it fell into neglect. Henry Herbert, the Earl of Powis, leased the property from the Crown in 1772, extensively landscaping the ruins, and his brother-in-law, Edward Clive, bought the castle outright in 1811. A mansion was constructed in the outer bailey but the remainder of the castle was left largely untouched, attracting an increasing number of visitors and becoming a popular location for artists. After 1900, Ludlow Castle was cleared of vegetation and over the course of the century it was extensively repaired by the Powis Estate and government bodies. In the 21st century it is still owned by the Earl of Powis and operated as a tourist attraction.

The architecture of Ludlow reflects its long history, retaining a blend of several styles of building. The castle is approximately 500 by 435 feet (152 by 133 m) in size, covering almost 5 acres (2.0 ha). The outer bailey includes the Castle House building, now used by the Powis Estate as offices and accommodation, while the inner bailey, separated by a trench cut out of the stone, houses the Great Tower, Solar block, Great Hall and Great Chamber block, along with later 16th century additions, as well as a rare, circular chapel, modelled on the shrine in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. English Heritage notes that the ruins represent "a remarkably complete multi-phase complex" and considers Ludlow to be "one of England's finest castle sites".

History

11th century

Ludlow Castle was probably founded by Walter de Lacy around 1075.[1] Walter had arrived in England in 1066 as part of William fitzOsbern's household during the Norman conquest of England.[2] FitzOsbern was made the Earl of Hereford and tasked with settling the area; at the same time, several castles were founded in the west of the county, securing its border with Wales.[2] Walter de Lacy was the earl's second in command, and was rewarded with 163 manors spread across seven counties, with 91 in Herefordshire alone.[2]

Walter began building a castle within the manor of Stanton Lacy; the fortification was originally called Dinham Castle, before it acquired its later name of Ludlow.[3] Ludlow was the most important of Walter's castles: as well as being at the heart of his new estates, the site also lay at a strategic crossroads over the Teme River, on a strong defensive promontory.[4] Walter died in a construction accident at Hereford in 1085 and was succeeded by his son, Roger de Lacy.[5]

The castle's Norman stone fortifications were added possibly as early as the 1080s onwards, and were finished before 1115, based around what is now the inner bailey of the castle, forming a stone version of a ringwork.[6] It had four towers and a gatehouse tower along the walls, with a ditch dug out of the rock along two sides, the excavated stone being reused for the building works, and would have been one of the first masonry castles in England.[7] With its circular design and grand entrance tower, it has been likened to the earlier Anglo-Saxon burgheat designs.[8] In 1096, Roger was stripped of his lands after rebelling against William II and they were reassigned to Roger's brother, Hugh.[9]

12th century

Hugh de Lacy died childless around 1115, and Henry I gave Ludlow Castle and most of the surrounding estates to Hugh's niece, Sybil, marrying her to Pain fitzJohn, one of his household staff.[9] Pain used Ludlow as his caput, the main castle in his estates, using the surrounding estates and knight's fees to support the castle and its defences.[10] Pain died in 1137 fighting the Welsh, triggering a struggle for the inheritance of the castle.[10] Robert fitzMiles, who had been planning to marry Pain's daughter, laid claim to it, as did Gilbert de Lacy, Roger de Lacy's son.[11] By now, King Stephen had seized the English throne, but his position was insecure and he therefore gave Ludlow to fitzMiles in 1137, in exchange for promises of future political support.[12]

A civil war between Stephen and the Empress Matilda soon broke out and Gilbert took his chance to rise up against Stephen, seizing Ludlow Castle.[13] Stephen responded by taking an army into the Welsh Marches, where he attempted to garner local support by marrying one of his knights, Joce de Dinan, to Sybil and granting the future ownership of the castle to them.[14] Stephen took the castle after several attempts in 1139, famously rescuing his ally Prince Henry of Scotland when the latter was caught on a hook thrown over the walls by the garrison.[15] Gilbert still maintained that he was the rightful owner of Ludlow, however, and a private war ensued between Joce and himself.[16] Gilbert was ultimately successful and retook the castle around a few years before the end of the civil war in 1153.[17] He ultimately left for the Levant, leaving Ludlow in the hands of firstly, his eldest son, Robert, and then, after Robert's death, his younger son, Hugh de Lacy.[18]

During this period, the Great Tower, a form of keep, was constructed by converting the entrance tower, probably either around the time of the siege of 1139, or during the war between Gilbert and Joce.[19] The old Norman castle had also begun to become too small for a growing household and, probably between 1140 and 1177, an outer bailey was built to the south and east of the original castle, creating a large open space.[20] In the process, the entrance to the castle shifted from the south to the east, to face the growing town of Ludlow.[21] Gilbert probably built the circular chapel in the inner bailey, resembling the churches of the Templar order which he later joined.[22]

Hugh took part in the Norman invasion of Ireland and in 1172 was made Lord of Meath; he spent much time away from Ludlow, and Henry II confiscated the castle in his absence, probably to ensure that Hugh stayed loyal while in Ireland.[23] Hugh died in Ireland in 1186 and the castle passed to his son, Walter, who was a minor and did not take charge of the property until 1194.[23] During Prince John's rebellion against Richard I in 1194, Walter joined in the attacks against the prince; Richard did not approve of this and confiscated Ludlow and Walter's other properties.[23] Walter de Lacy offered to buy back his land for 1,000 marks, but the offer was rejected until in 1198 the vast sum of 3,100 marks was finally agreed.[24][lower-alpha 1]

13th century

Walter de Lacy travelled to Ireland in 1201 and the following year his properties, including Ludlow Castle, were once again confiscated to ensure his loyalty and placed under the control of William de Braose, his father-in-law.[26] Walter's lands were returned to him, subject to the payment of a fine of 400 marks, but in 1207 his disagreements with royal officials in Ireland led to King John seizing the castle and putting it under the control of William again.[27][lower-alpha 1] Walter reconciled himself with John the following year, but meanwhile William himself had fallen out with the King; violence broke out and both Walter and William took refuge in Ireland, with John taking control of Ludlow yet again.[27] It was not until 1215 that their relationship recovered and John agreed to give Ludlow back to Walter.[28] At some point during the early 13th century, the innermost bailey was constructed in the castle, creating an additional private space within the inner bailey.[29]

In 1223, King Henry III met with the Welsh prince Llywelyn ab Iorwerth at Ludlow Castle for peace talks, but the negotiations were unsuccessful.[28] The same year Henry became suspicious of Walter's activities in Ireland and, among other measures to secure his loyalty, Ludlow Castle was taken over by the Crown for a period of two years.[30] This was cut short in May 1225 when Walter carried out a campaign against Henry's enemies in Ireland and paid the King 3,000 marks for the return of his castles and lands.[31] During the 1230s, however, Walter had accumulated a thousand pounds of debt to Henry and private moneylenders which he was unable to repay.[32] As a result, in 1238 he gave Ludlow Castle as collateral to the King, although the fortification was returned to him sometime before his death in 1241.[32]

Walter's granddaughters Maud and Margaret were due to inherit Walter's remaining estates on his death, but they were still unmarried, making it hard for them to hold property in their own right.[32] Henry informally divided the lands up between them, giving Ludlow to Maud and marrying her to one of his royal favourites, Peter de Geneva, cancelling many of the debts they had inherited from Walter at the same time.[33] Peter died in 1249 and Maud married a second time, this time to Geoffrey de Geneville, a friend of the Prince Edward, the future king.[34] In 1260, Henry officially split up Walter's estate, allowing Geoffrey to retain the castle.[35]

Henry lost control of power in the 1260s, resulting in the Second Barons' War across England.[36] Following the Royalist defeat in 1264, the rebel leader Simon de Montfort seized Ludlow Castle, but it was recaptured shortly afterwards by Henry's supporters, probably led by Geoffrey de Geneville.[36] Prince Edward escaped from captivity in 1265 and met up with his supporters at the castle, before commencing his campaign to retake the throne, culminating in de Montfort's defeat at Evesham later that year.[36] Geoffrey continued to occupy the castle for the rest of the century under Edward I's rule, prospering until his death in 1314.[37] Geoffrey built the Great Hall and the Solar block during his tenure of the castle, either between 1250 and 1280, or later, in the 1280s and 1290s.[38][lower-alpha 2] The town walls of Ludlow also began to be constructed in the 13th century, probably from 1260 onwards, and these were linked to the castle to form a continuous ring of defences around the town.[40]

14th century

.jpg.webp)

Geoffrey and Maud's oldest granddaughter, Joan, married Roger Mortimer in 1301, giving Mortimer control of Ludlow Castle.[41] Around 1320, Roger built the Great Chamber block alongside the existing Great Hall and Solar complex, copying what was becoming a popular tripartite design for domestic castle buildings in the 14th century; an additional building was also constructed by Roger on the location of the later Tudor Lodgings, and the Guardrobe Tower was added to the curtain wall.[42] Between 1321 and 1322 Mortimer found himself on the losing side of the Despenser War and, after being imprisoned by Edward II, he escaped from the Tower of London in 1323 into exile.[43]

While in France, Mortimer formed an alliance with Queen Isabella, Edward's estranged wife, and together in 1327 they seized power in England.[43] Mortimer was made the Earl of March and became extremely wealthy, possibly entertaining Edward III at the castle in 1329.[44] The earl built a new chapel in the Outer Bailey, named after Saint Peter, honouring the saint's day on which he had escaped from the Tower.[45] Mortimer's work at Ludlow was probably intended to produce what the historian David Whitehead has termed a "show castle" with chivalric and Arthurian overtones, echoing the now archaic Norman styles of building.[46] Mortimer fell from power the following year but his widow Joan was permitted to retain Ludlow.[47]

Ludlow Castle gradually became the Mortimer family's most important property, but for much of the rest of the century its owners were too young to control the castle personally.[48] The castle was first briefly inherited by Mortimer's son, Edmund, and then in 1331 Mortimer's young grandson, Roger, who eventually became a prominent soldier in the Hundred Years War.[49] Roger's young son, Edmund, inherited the castle in 1358, and also grew up to become involved in the war with France.[50] Both Roger and Edmund used a legal device called "the use", effectively giving Ludlow Castle to trustees during their lifetimes in exchange for annual payments; this reduced their tax liabilities and gave them more control over the distribution of the estates on their deaths.[50] Edmund's son, another Roger, inherited the castle in 1381, but King Richard II took the opportunity of Roger's minority to exploit the Mortimer estates until they were put into the control of a committee of major nobles.[51] When Roger died in 1398, Richard again took wardship of the castle on behalf of the young heir, Edmund, until he was deposed from power in 1399.[52]

15th century

Ludlow Castle was in the wardship of King Henry IV, when the Owain Glyndŵr revolt broke out across Wales.[54] Military captains were appointed to the castle to protect it from the rebel threat, in the first instance John Lovel and then Henry's half-brother, Sir Thomas Beaufort.[55] Roger Mortimer's younger brother, Edmund, set out from the castle with an army against the rebels in 1402, but was captured at the Battle of Bryn Glas.[55] Henry refused to ransom him, and he eventually married one of Glyndŵr's daughters, before dying during the siege of Harlech Castle in 1409.[55]

Henry placed the young heir to Ludlow, another Edmund Mortimer, under house arrest in the south of England, and kept a firm grip on Ludlow Castle himself.[56] This persisted until Henry V finally granted Edmund his estates in 1413, with Edmund going on to serve the Crown overseas.[56] As a result, the Mortimers rarely visited the castle during the first part of the century, despite the surrounding town having become prosperous in the wool and cloth trades.[57] Edmund fell heavily into debt and having sold his rights to his Welsh estates to a consortium of nobles, before dying childless in 1425.[58]

The castle was inherited by Edmund's sister's young son, Richard the Duke of York, who took possession in 1432.[59] Richard took a keen interest in the castle, which formed the administrative base for his estates around the region, possibly living there in the late 1440s and definitely residing there for much of the 1450s.[60] Richard also established his sons, including the future Edward IV, and their household at the castle in the 1450s, and was possibly responsible for rebuilding the northern part of the Great Tower during this period.[61]

The Wars of the Roses broke out between the Lancastrian and Richard's Yorkist factions in the 1450s. Ludlow Castle did not find itself in the front-line of most of the conflict, instead acting as a safe retreat away from the main fighting.[62] An exception to this was the Battle of Ludford Bridge which took place just outside the town of Ludlow in 1459, resulting in a largely bloodless victory for the Lancastrian Henry VI.[63] After the battle, in a bid to break Richard's power over the region, Edmund de la Mare was placed in charge of the castle as constable, with John Talbot, the Earl of Shrewsbury, being given the wider lordship.[63] Richard was killed in battle in 1460, and his son Edward seized the throne the following year, retaking control of Ludlow Castle and merging it with the property of the Crown.[64]

The new Edward IV visited the castle regularly and established a council there to govern his estates in Wales.[65] He probably conducted only modest work on the property, although he may could have been responsible for the remodelling of the Great Tower.[65] In 1473, possibly influenced by his own childhood experiences at Ludlow, Edward sent his eldest son, the future Edward V, and his brother Prince Richard to live at the castle, which was also made the seat of the newly created Council in the Marches of Wales.[66] By now Ludlow had become primarily residential, rather than military, but was still rich in chivalric connotations and a valuable symbol of the Yorkist authority and their claim to the throne.[67] Edward died in 1483, but after Henry VII took the throne in 1485 he continued to use Ludlow Castle as a regional base, granting it to his son, Prince Arthur, in 1493, and reestablishing the dormant Council in the Marches at the property.[68]

16th century

In 1501, Prince Arthur arrived in Ludlow for his honeymoon with his bride Catherine of Aragon, before dying the following year.[69] The Council in the Marches of Wales continued to operate, however, under the guidance of its president, Bishop William Smyth.[70] The council evolved into a combination of a governmental body and a court of law, settling a range of disputes across Wales and charged with maintaining general order, and Ludlow Castle became effectively the capital of Wales.[71]

Mary Tudor, daughter of Catherine of Aragon and Henry VIII, spent 19 months at Ludlow overseeing the Council of the Marches between 1525 and 1528, along with her entourage of servants, advisors, and guardians.[72] The relatively small sum of £5 was spent restoring the castle before her arrival.[69][lower-alpha 3] The council's wide-ranging role was reinforced in legislation in 1534, and its purpose was further elaborated in the Act of Union of 1543; some presidents, such as Bishop Rowland Lee, used its harsher powers extensively to execute local criminals, but later presidents typically preferred to punish with the pillory, whipping or imprisonment in the castle.[74] The Great Chamber itself was used as the council's meeting room.[75]

The establishment of the Council in Ludlow Castle gave it a new lease of life, during a period in which many similar fortifications were falling into decay.[76] By the 1530s, the castle needed considerable renovation; Lee began work in 1534, borrowing money to do so, but Sir Thomas Engleford complained the following year that the castle was still unfit for habitation.[77] Lee repaired the castle roofs, probably using lead from the Carmelite friary in the town, and using the fines imposed and the goods confiscated by the court.[78] He later claimed that the work on the castle would have cost around £500, had the Crown had to pay for it all directly.[79] The porter's lodge and prison were built in the outer bailey around 1552.[80] The woods around the castle were gradually cut down during the 16th century.[81]

Elizabeth I, influenced by her royal favourite Robert Dudley, appointed Sir Henry Sidney as President of the Council in 1560, and he took up residence at Ludlow Castle.[82] Henry was a keen antiquarian with an interest in chivalry, and used his post to restore much of the castle in a late-perpendicular style.[83] He extended the castle by building family apartments between the Great Hall and Mortimer's Tower, and used the former royal apartments as a guest wing, starting a tradition of decorating the Great Hall with the coats of arms of council officers.[83] The larger windows in the castle were glazed, a clock installed and water piped into the castle.[84] The judicial facilities were improved with a new courthouse converted out of the 14th-century chapel, facilities for prisoners and storage facilities for the court records, Mortimer's Tower in the outer bailey being turned into a record depository.[85] The restoration was generally sympathetic and, although it included a fountain, a real tennis court, walks and viewing platform, it was less ephemeral a make-over than seen in other castle restorations of the period.[86]

17th century

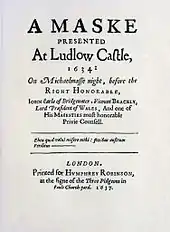

The castle was luxuriously appointed by the 17th century, with an expensive, but grand, household based around the Council of the Marches.[87] The future Charles I was declared Prince of Wales in the castle by James I in 1616, and Ludlow was made his principal castle in Wales.[88] A company called the "Queen's Players" entertained the Council in the 1610s, and in 1634 John Milton's masque Comus was performed in the Great Hall for John Egerton, Earl of Bridgewater.[89] The Council faced increased criticism over its legal practices, however, and in 1641 an Act of Parliament stripped it of its judicial powers.[90]

When the English Civil War broke out in 1642 between the supporters of King Charles and those of Parliament, Ludlow and the surrounding region supported the Royalists.[91] A Royalist garrison was put in place in the town, under the command of Sir Michael Woodhouse, and the defences were strengthened, with artillery being brought from nearby Bringwood Forge for the castle.[92] As the war turned against the King in 1644, the garrison was drawn down to provide reinforcements for the field army.[93] The military situation deteriorated and in 1645 the remaining outlying garrisons were drawn in to protect Ludlow itself.[93] In April 1646 Sir William Brereton and Colonel John Birch led a Parliamentary army from Hereford to take Ludlow; after a short siege, Woodhouse surrendered the castle and town on good terms on 26 May.[94]

During the years of the interregnum, Ludlow Castle continued to be run by Parliamentarian governors, the first being the military commander Samuel More.[95] There was a Royalist plot to retake the castle in 1648, but no other military activity took place.[96] The most valuable items in the castle were removed shortly after the siege, and the remainder of the luxurious furnishings were sold off in the town in 1650.[97] The castle was initially kept garrisoned, but in 1653, most of the weapons in the castle were removed on the grounds of security and sent to Hereford, then in 1655 the garrison was disbanded altogether.[95] In 1659, the political instability in the Commonwealth government led to the castle being regarrisoned by 100 men under the command of William Botterell.[95]

Charles II returned to the throne in 1660 and reinstated the Council of the Marches in 1661, but the castle never recovered from the war.[98] Richard Vaughan, the Earl of Carbery, was appointed president and given £2,000 to renovate the castle, and between 1663 and 1665, a company of infantry soldiers was garrisoned there, overseen by the earl, with the task of safeguarding the money and contents of the castle as well as the ammunition for the local Welsh militia.[99][lower-alpha 4] The Council of the Marches failed to reestablish itself and was finally disbanded in 1689, bringing an end to Ludlow Castle's role in government.[100] Uncared for, the condition of the castle rapidly deteriorated.[101]

18th century

The castle remained in disrepair, and in 1704 its governor, William Gower, proposed dismantling the castle and building a residential square on the site instead, in a more contemporary style.[102] His proposal was not adopted but, by 1708, only three rooms were still in use in the hall range, many of the other buildings in the inner bailey had fallen into disuse, and much of the remaining furniture was rotten or broken.[101] Shortly after 1714, the roofs were stripped of their lead and the wooden floors began to collapse; the writer Daniel Defoe visited in 1722, and noted that the castle "is in the very Perfection of Decay".[103] Nonetheless, some rooms remained usable for many years afterwards, possibly as late as the 1760s and 1770s, when drawings show the entrance block to the inner bailey to still be intact, and visitors remarked on the good condition of the round chapel.[104] The stonework became overgrown with ivy, trees and shrubs, and by 1800 the chapel of Saint Mary Magdalene had finally degenerated into ruin.[105]

Alexander Stuart, an Army captain who served as the last governor of the castle, stripped down what remained of the fortification in the mid-1700s.[106] Some of the stone was reused to build the Bowling Green House – later renamed the Castle Inn – on the north end of the tennis courts, while the north side of the outer bailey was used to make the bowling green itself.[107] Stuart lived in a house in Ludlow itself, but decorated the Great Hall with the remains of the castle armoury, and may have charged visitors for admittance.[108]

It became fashionable to restore castles as private homes, and the future George II may have considered making Ludlow habitable again, but was deterred by the estimated costs of £30,000.[109][lower-alpha 5] Henry Herbert, the Earl of Powis, later became interested in acquiring the castle and in 1771 approached the Crown about leasing it.[110] It is uncertain if he intended to further strip the castle of its materials or, more likely, if he intended to turn it into a private home, but the castle was, according to Powis' surveyor's report later that year, already "extremely ruinous", the walls "mostly rubble and the battlements greatly decayed".[111] The Crown offered a 31-year lease at £20 a year, which Powis accepted in 1772, only to die shortly afterwards.[112]

Henry's son, George Herbert, maintained the lease and his wife, Henrietta, constructed gravel-laid public walks around the castle, dug into the surrounding cliffs, and planted trees around the grounds to improve the castle's appearance.[113] The castle walls and towers were given superficial repairs and tidied up, usually when parts threatened to collapse, and the interior of the inner bailey levelled, costing considerable sums of money.[114] The landscape also required expensive maintenance and repairs.[115]

The town of Ludlow was increasingly fashionable and frequented by tourists, with the castle forming a particularly popular attraction.[116] Thomas Warton published an edition of Milton's poems in 1785, describing Ludlow Castle and popularising the links to Comus, reinforcing the castle's reputation as a picturesque and sublime location.[117] The castle became a topic for painters interested in these themes: J. M. W. Turner, Francis Towne, Thomas Hearne, Julius Ibbetson, Peter de Wint and William Marlowe all produced depictions of the castle during the late 18th and early 19th centuries, usually taking some artistic licence with the details in order to produce atmospheric works.[118]

19th century

Lord Clive, George's brother-in-law and heir, attempted to acquire the lease after 1803, citing the efforts that the family had put into restoring the castle.[119] He faced competition for the lease from the government's Barrack Office, who were considering using the castle as a French prisoner-of-war camp for up to 4,000 inmates from the Napoleonic wars.[119] After some extensive discussions the prisoner-of-war plan was finally dropped, and Lord Clive, by now declared the Earl of Powis, was offered the chance to buy the castle outright for £1,560, which he accepted in 1811.[120][lower-alpha 6]

Between 1820 and 1828 the earl had converted the abandoned tennis court and the Castle Inn – which he closed in 1812 after buying the castle – into a new, grand building, called Castle House, overlooking the north side of the outer bailey.[121] By the 1840s the house had been leased out, first to George Hodges and his family, and then to William Urwick and to Robert Marston, all important members of the local landowning classes.[122] The mansion included a drawing room, dining room, study, servants' quarters, a conservatory and grapevines, and in 1887 was worth £50 a year in rent.[123]

During the 19th century, vegetation continued to grow over the castle's stonework, although after a survey by Arthur Blomfield in 1883, which highlighted the damage being caused by the ivy, attempts were made to control the plants, cleaning them off many of the walls.[124] Ludlow Castle was held in high esteem by Victorian antiquarians, George Clark referring to it as "the glory of the middle marches of Wales" and as being "probably without rival in Britain" for its woodland setting.[125] When Ludlow became connected to the growing railway network in 1852, the numbers of tourists to the castle increased, with admission costing six pence in 1887.[102] The castle was put to a wide range of uses. The grassy areas of the bailey were kept cropped by grazing sheep and goats, and used for fox hunting meetings, sporting events and agricultural shows; parts of the outer bailey was used as a timber yard, and, by the turn of the century, the old prison was used as an ammunition store by the local volunteer militia.[126]

20th century

W. H. St John Hope and Harold Brakspear began a sequence of archaeological investigations at Ludlow Castle in 1903, publishing their conclusions in 1909 in an account which continues to be held in regard by modern academics.[127] Christian Herbert, the Earl of Powis, cleared away much of the ivy and vegetation from the castle stonework.[128] In 1915 the castle was declared an ancient monument by the state, but it continued to be owned and maintained by the earl and trustees of the Powis estate.[129]

The castle was increasingly rigorously maintained, and during the 1910s and 1920s the larger trees around the castle were cut down, and the animals were cleared from the inner and outer baileys on the basis that they posed a health and safety risk to visitors.[130] The 1930s saw a major effort to clear the remaining vegetation from the castle, the cellars were cleared of debris by the government's Office of Works and the stable block was converted into a museum.[130] Tourists continued to visit the castle, with the 1920s and 1930s seeing many day-trips by teams of workers in the region encouraged by the growth in motor transport.[131] The open spaces inside the castle were used by the local townsfolk for football matches and similar events, and in 1934 Milton's Comus was restaged in the castle to mark the 300th anniversary of the first such event.[132]

Castle House in the outer bailey was leased to the diplomat Sir Alexander Stephen in 1901, who carried out extensive work on the property in 1904, extending and modernising the north end of the house, including constructing a billiard room and a library; he estimated the cost of the work to be around £800.[133] Castle House continued to be leased out by the Powis estate to wealthy individuals up until the Second World War.[134] One such lessee, Richard Henderson observed that he had spent around £4,000 maintaining and upgrading the property, and the rentable value of the property rose from £76 to £150 over the period.[134][lower-alpha 7]

During the Second World War the castle was used by the Allied military.[135] The Great Tower was used as a look-out post and United States' forces used the castle gardens for baseball games.[136] Castle House fell empty after the death of its final lessee, James Geenway; the house was then briefly requisitioned in 1942 by the Royal Air Force and turned into flats for key war workers, causing extensive damage later estimated at £2,000.[137] In 1956, Castle House was de-requisitioned and sold by the Earl of Powis the following year to Ludlow Borough Council for £4,000, which rented out the flats.[138]

During the 1970s and early 1980s the Department of the Environment assisted the Powis estate by lending government staff to repair the castle.[139] Visitor numbers were falling, however, in part due to the dilapidated condition of the property, and the estate became increasingly unable to afford to maintain the castle.[139] After 1984, when the function of the department was taken over by English Heritage, a more systematic approach was put into place.[140] This based around a partnership in which the Powis Estate would retain ownership of the castle and develop visitor access, in exchange for a £500,000 contribution from English Heritage for a jointly-funded programme of repairs and maintenance, delivered through specialist contractors.[141] This included repairs to the parts of the curtain wall, which collapsed in 1990, and the redevelopment of the visitor's centre.[142] Limited archaeological excavation was carried out in the outer bailey between 1992 and 1993 by the City of Hereford Archaeology Unit.[143]

21st century

In the 21st century, Ludlow Castle is owned by John Herbert, the current Earl of Powis, but is held and managed by the Trustees of the Powis Castle Estate as a tourist attraction.[144] The castle was receiving over 100,000 visitors a year by 2005, more than in previous decades.[145] The castle traditionally hosts a Shakespearean play as part of the annual cultural Ludlow Festival in the town, and is at the centre of the Ludlow Food and Drink Festival each September.[146]

English Heritage considers Ludlow to be "one of England's finest castle sites", with the ruins representing "a remarkably complete multi-phase complex".[147] It is protected under UK law as a Scheduled Monument and a Grade I listed building.[148] By the 21st century, however, Castle House had become dilapidated and English Heritage placed it on its "at risk" register.[149] In 2002, the Powis Estate repurchased the property from the South Shropshire District Council for £500,000, renovating it and converting it for use as offices and rental apartments, reopening the building in 2005.[150]

Architecture

Ludlow Castle sits on a rocky promontory, overlooking the modern town of Ludlow on lower ground to the east, while the ground slopes steeply from the castle to the rivers Corve and Teme to the south and west, about 100 feet (30 m) below.[151] The castle is broadly rectangular in shape, and approximately 500 by 435 feet (152 by 133 m) in size, covering almost 5 acres (2.0 ha) in total.[152] The interior is divided into two main parts: an inner bailey which occupies the north-west corner and a much larger outer bailey.[153] A third enclosure, known as the innermost bailey, was created in the early 13th century when walls were built to enclose the south-west corner of the inner ward.[154] The castle's walls are linked to Ludlow's medieval town wall circuit on the south and east sides.[152] The castle is built from a range of different types of stone; the Norman stone work is constructed from greenish-grey siltstone rubble, with the ashlar and quoin features carved from red sandstone, with the later work primarily using local red sandstone.[155]

Outer bailey

The outer bailey is entered through a gatehouse; inside, the space within the curtain walls is divided into two. On the north side of the outer bailey is Castle House and its gardens; the house is a two-storeyed property, based around the old walls of the tennis court and the Castle Inn, and the curtain wall.[156] The north end of Castle House butts onto Beacon Tower, overlooking the town.[157]

The other half of the outer bailey houses the 16th-century porter's lodge, prison and stable block which run along its eastern edge.[158] The porter's lodge and prison comprise two buildings, 40 feet (12 m) and 58 by 23 feet (17.7 by 7.0 m) across, both two-storeyed and well built in ashlar stone, with a stable block on the far end, more crudely built in stone and 66 by 21 feet (20.1 by 6.4 m) in size.[159] The exterior of the prison was originally decorated with the coats of arms of Henry, the Earl of Pembroke, and Queen Elizabeth I, but these have since been destroyed, as have the barred windows which once protected the property.[160]

Along the south of the bailey are the remains of St Peter's, a former 14th-century chapel, approximately 21 by 52 feet (6.4 by 15.8 m) in size, later converted to a courthouse by the addition of an extension reaching up to the western curtain wall.[161] The courtroom occupied the whole of the combined first floor with records kept in the rooms underneath.[161] The south-west corner of the outer bailey is cut off by a modern wall from the rest of the bailey.[162]

The western curtain wall is approximately 6-foot-5-inch (1.96 m) thick, and guarded by the 13th-century Mortimer's Tower, 18 feet (5.5 m) across externally, with a ground floor vaulted chamber inside, 12-foot-9.5-inch (3.899 m) large.[163] When first built, Mortimer's Tower was a three-storey gateway with an unusual D-shaped design, possibly similar to those at Trim Castle in Ireland, but in the 15th century the entrance way was blocked up to turn it into a conventional mural tower, and in the 16th century an additional internal floor was inserted.[164] The tower is now roofless, although it was roofed as late as the end of the 19th century.[165]

Inner bailey

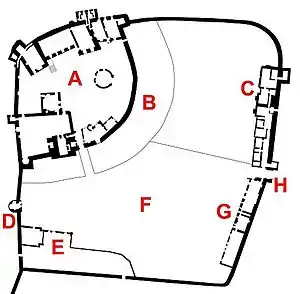

Period: black – 11th/12th century; purple – 12th century; blue – 13th century; yellow – 14th century; orange- 15th century; red – 16th century; light purple – 17th century; shading shows destroyed buildings

The inner bailey represents the extent of the original Norman castle and is protected by a curtain wall between 5-foot (1.5 m) and 6-foot (1.8 m) thick.[166] On the south and west sides the wall is protected by a ditch, originally up to 80-foot (24 m) deep, cut out of the rock and navigated by a bridge which still contains part of the ashlar stone of its 16th century predecessor.[167] Within the inner bailey, a separate area, called the innermost bailey, was created by the addition of a 5-foot (1.5 m) thick stone wall around the south-west corner in the early 13th century.[168]

The gatehouse to the inner bailey has the coats of arms of Sir Henry Sidney and Queen Elizabeth I displayed over it, dating to 1581, and was originally a three-storeyed building with transomed windows and fireplaces, probably used as the lodgings for the judges.[169] There were probably additional heraldic supporters displayed alongside the arms, since lost.[170] A porter's lodge would have been on the right hand side of the entrance to control access, with the rooms accessed by a spiral staircase in a protruding tower, with prominent triple chimneys, since lost.[171] Alongside the gatehouse was originally a half-timbered building, possibly a laundry, approximately 48 by 15 feet (14.6 by 4.6 m), which has since been lost.[172]

On the east side of the bailey is the 12th-century chapel of Saint Mary Magdalene. The circular, Romanesque design of the chapel is unusual, with only three similar examples existing in England, at Castle Rising, Hereford and Pevensey.[173] Built from sandstone, the circular design imitates the shrine at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre.[174] Originally the chapel had a nave, a square presbytery, 3.8 by 3.8 metres (12 by 12 ft) in size, and a chancel, but this design was heavily altered in the 16th century and only the nave survives.[175] Although roofless, the nave survives to its full height and is 26 feet 3 inches (8.00 m) in diameter, visibly divided into two sections by different bands of stonework, and with some plaster surviving on the lower level.[176] Around the inside of the nave are 14 arcaded bays in the walls.[177]

The north end of the bailey is occupied by a range of buildings, the Solar block, the Great Hall and the Great Chamber block, with the Tudor Lodgings in the north-east corner. The Tudor Lodgings take the form of two rhomboids to fit into the space provided by the curtain wall, divided by a cross-wall, the west side being approximately 33 by 15 feet (10.1 by 4.6 m), and the east side 33 by 21 feet (10.1 by 6.4 m).[178] They were entered by a shared spiral staircase, a design used in various episcopal palaces in the 16th century, and originally provided sets of individual offices and personal rooms for the court officials, later being converted into two distinct apartments.[179]

The Great Chamber block adjoining the Tudor Lodgings dates from around 1320.[180] Another rhomboid design, approximately 53 by 34 feet (16 by 10 m) across, this originally had its main chamber on the first floor, but has been much altered over the subsequent years.[181] The carved corbel heads that survive on the first floor may represent Edward II and Queen Isabella.[182] Behind the Great Chamber block is the Guardrobe Tower, a four storeyed construction, providing a combination of bed chambers and guardrobes.[183]

In the 13th-century Great Hall, the hall itself was also positioned on the first floor, originally fitted with a wooden floor supported by stone pillars in the basement, and a massive wooden roof.[184] It was 60 by 30 feet (18.3 by 9.1 m) across: this 2:1 ratio between length and width was typical for castle halls of this period.[184] The hall was reached by a flight of stone steps at the west end, and lit by three tall, trefoiled windows, each originally with its own window seat and south-facing to receive the sunlight.[185] Originally the hall had an open fire in the centre, which was normal for the 13th century, but the middle window was turned into a more modern fireplace around 1580.[186]

To the west of the Great Hall is the three-storeyed Solar block, an irregular oblong measuring up to 26 by 39 feet (7.9 by 11.9 m) in size.[187] The first floor chamber would probably have been used as a solar, with the cellar being used as a service area.[188] The Great Hall and Solar block were built at the same time in the 13th century, the builders carving out the inside of the old Norman tower behind them in the process.[189] They were probably built in two phases and were originally intended to be smaller, less grand buildings, only for the design to be changed about halfway through construction; they were finished in a rushed manner, the traces of which can still be seen, along with other changes made in the 16th and 17th centuries.[190]

The North-West and North-East towers behind the northern range are Norman in origin, from the 11th and early 12th century. When first built, they were created by pushing or folding the line of the curtain wall outwards to create the desired external shape, and then adding timber floors and a timber wall at the back, rather than being designed as individual buildings.[191] The timber parts of the towers were later replaced in stone, and incorporated into the later range of buildings. The North-East Tower, also known as the Pendover Tower, was originally two-storeys high, with a third floor added on in the 14th century, followed by an extensive remodelling of the inside in the 16th century.[192] It has chamfered angles on the external corners to make it harder to attack the stonework, although this has weakened the structural strength of the tower as a whole.[193] The North-West Tower had similar chamfered corners, but the Closet Tower was built alongside it in the 13th century, altering the external appearance.[194] Two more Norman towers survive in the innermost bailey, the West Tower, also known as the Postern Tower, because it contained a postern gate, and the South-West tower, also called the Oven Tower, on account of its cooking facilities.[195] The Norman towers looked out towards Wales, probably to make a symbolic statement.[196]

A range, now lost, once stretched from the innermost bailey towards the Great Hall, including a large stone house running along the curtain wall, 54 by 20 feet (16.5 by 6.1 m) in size, and on the other side of the innermost bailey, the Great Kitchen, 31 by 23 feet (9.4 by 7.0 m) in size, built around the same time as the Great Hall, and an oven building, since lost, 21 by 27 feet (6.4 by 8.2 m).[197]

The Great Tower, or keep, is on the south side of the innermost bailey. A roughly square building, four storeys tall, most of its walls are 8-foot-6-inch (2.59 m) thick, with the exception of its newer northern facing wall, only 7-foot-6-inch (2.29 m) thick.[198] The Great Tower was constructed in several stages. Originally it was a relatively large gatehouse in the original Norman castle, probably with accommodation over the gateway, before being extended to form the Great Tower in the mid-12th century, although still being used as a gatehouse for the inner bailey.[199] When the innermost bailey was created in the early 13th century, the gateway was then filled in and a new gateway cut into the inner bailey wall just to the east of the Great Tower.[200] Finally, the north side of the tower was rebuilt in the mid-15th century to produce the Great Tower that appears today.[201] The keep has a vaulted basement, 20-foot (6.1 m) high, with Norman wall arcading, and a row of windows along the first floor, since mostly blocked.[202] The arcading echoes that in the chapel, and probably dates from around 1080.[203] The windows and large entrance-way would have looked impressive, but would also have been very hard to defend; this form of tower probably reflected earlier Anglo-Saxon high-status towers and was intended to display lordship.[204] The first floor originally formed a tall hall, 29 by 17 feet (8.8 by 5.2 m) across, which was subsequently subdivided into two separate floors.[205]

Early 12th century chapel

The chapel of St Mary Magdalene, showing the two levels of stonework and surviving plasterwork...

The chapel of St Mary Magdalene, showing the two levels of stonework and surviving plasterwork... ...the entrance...

...the entrance... ...the interior, with arcaded bays...

...the interior, with arcaded bays... ...and carved corbel head.

...and carved corbel head.

See also

Notes

- The medieval mark was worth two-thirds of an English pound; 400, 1,000 marks and 3,100 marks were the equivalent of £240, £666 and £2,066 respectively. It is impossible to accurately compare medieval financial sums with their modern equivalents; as a comparative example, an average English baron of the period had an annual income of around £200.[25]

- The dating of the Great Hall and the Solar block depends on an analysis of their stylistic features and the historical events during the period; there are no documentary records available of the construction work. There has been consensus since Hope's work at the beginning of the 20th century that they were built in the late 13th century, but the precise date is uncertain. The historian Richard Morriss concludes that they date from the 1280s or 1290s, but Michael Thompson argues in favour of the construction taking place between 1250 and 1280.[39]

- It is challenging to accurately compare 16th-century and modern financial sums. £5 in 1525 would be worth between £3,059 and £1,101,000 in 2013 terms, depending on the financial measure used. £500 in 1534 would be worth between £306,000 and £110 million in 2013 terms.[73]

- It is challenging to accurately compare 17th-century and modern financial sums. £2,000 in 1661 would be worth between £3.2 million and £49 million in 2013 terms, depending on the financial measure used.[73]

- It is challenging to accurately compare 18th-century and modern financial sums. £30,000 in 1720 would be worth between £55 million and £440 million in 2013 terms, depending on the financial measure used. £20 in 1772 would be worth between £2,200 and £38,000 in 2013 terms.[73]

- Comparing 19th-century and modern financial sums depends on the financial measure used. £1,560 in 1811 would be worth between £99,000 and £5.2 million in 2013 terms. £50 in 1887 would be worth between £4,900 and £62,000 in 2013 terms. Six pence in 1887 would be worth between £2.40 and £18 in 2013 terms.[73]

- £800 in 1904 would be worth between £86,000 and £673,000 in 2013 terms, depending on the financial measure used. £4,000 in 1928 would be worth between £630,000 and £1.4 million; £2,000 in 1945 would be worth between £230,000 and £320,000; £4,000 in 1956 would be worth between £81,000 and £300,000.[73]

References

- Renn 1987, pp. 55–58; Coplestone-Crow 2000a, pp. 21

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, p. 21

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, pp. 21–22

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, p. 22; Pounds 1994, p. 69

- Renn 1987, p. 57

- Renn 2000, pp. 125–126; Goodall 2011, p. 79; Pounds 1994, p. 11; "List Entry", English Heritage, archived from the original on 26 January 2014, retrieved 26 November 2014

- Renn 2000, pp. 125–126; Goodall 2011, p. 79; Creighton 2012, p. 83

- Pounds 1994, p. 11; Liddiard 2005, pp. 21–22

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, p. 22

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, p. 25

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, pp. 25–26

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, p. 26

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, pp. 26–27

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, p. 27

- Renn 1987, p. 55; Coplestone-Crow 2000a, p. 28

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, pp. 30–33

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, p. 34

- Coplestone-Crow 2000a, p. 34; Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 35

- Renn 2000, p. 133

- Renn & Shoesmith 2000, pp. 191–194

- Renn & Shoesmith 2000, p. 191

- Coppack 2000, p. 150

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 35

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, pp. 35–36

- Pounds 1994, p. 147

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 36

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 37

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 38

- White 2000, p. 140

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 39

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, pp. 38–39

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 40

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, pp. 40–42

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 41

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 42

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 43

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, pp. 43–44

- Morriss 2000, p. 166; Thompson 2000, p. 170

- Hope 1909, p. 276; Morriss 2000, p. 166; Thompson 2000, p. 170

- Renn & Shoesmith 2000, p. 194

- Harding 2000, p. 45

- Pounds 1994, p. 190; Thompson 2000, pp. 170–171; Shoesmith 2000b, p. 175; Whitehead 2000, p. 100

- Harding 2000, p. 46

- Harding 2000, pp. 47–48

- Coplestone-Crow 2000b, p. 44; Harding 2000, p. 47

- Whitehead 2000, p. 100

- Harding 2000, p. 48

- Harding 2000, pp. 48–54

- Harding 2000, pp. 48–49

- Harding 2000, pp. 50–51

- Harding 2000, pp. 51–52

- Harding 2000, p. 53

- The tile is from The Shropshire Hills Discovery Centre, holding number SRCHM A08248; origins described on museum label

- Harding 2000, pp. 53–54

- Harding 2000, p. 54

- Harding 2000, p. 55

- Griffiths 2000, pp. 57–58

- Griffiths 2000, p. 59; Harding 2000, p. 55

- Griffiths 2000, p. 57; Harding 2000, p. 55

- Griffiths 2000, pp. 59–60

- Griffiths 2000, p. 67; Whitehead 2000, p. 101

- Whitehead 2000, p. 101; Griffiths 2000, p. 60

- Griffiths 2000, pp. 64–65

- Griffiths 2000, p. 65; Faraday 2000, p. 69

- Griffiths 2000, p. 67; Whitehead 2000, p. 102

- Faraday 2000, p. 69; Goodall 2011, p. 383

- Whitehead 2000, pp. 101–102

- Griffiths 2000, p. 67; Faraday 2000, pp. 69–70

- Whitehead 2000, p. 102

- Faraday 2000, p. 70

- Faraday 2000, pp. 69–70; Cooper 2014, p. 138; Lloyd n.d., p. 3

- Goodall 2011, p. 427

- Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, retrieved 3 December 2014

- Faraday 2000, p. 71; Cooper 2014, p. 138

- Lloyd n.d., p. 15

- Faraday 2000, p. 77; Pounds 1994, pp. 256–257

- Whitehead 2000, p. 103; Faraday 2000, p. 77

- Faraday 2000, p. 70; Whitehead 2000, p. 103; Shoesmith 2000b, p. 181

- Faraday 2000, p. 76

- Stone 2000, p. 209

- Whitehead 2000, p. 106

- Whitehead 2000, p. 103; Goodall 2011, p. 453

- Whitehead 2000, p. 103

- Faraday 2000, p. 77; Goodall 2011, p. 453

- Faraday 2000, p. 77; Curnow & Kenyon 2000, p. 195; Remfry & Halliwell 2000, pp. 203–204

- Whitehead 2000, pp. 103–104

- Hughes 2000, p. 89; Faraday 2000, p. 76

- Whitehead 2000, p. 105

- Whitehead 2000, p. 105; Lloyd n.d., p. 17; Faraday 2000, p. 76

- Faraday 2000, p. 79

- Knight 2000, p. 83

- Knight 2000, pp. 84–85; Faraday 2000, p. 80

- Knight 2000, p. 87

- Knight 2000, p. 88

- Knight 2000, p. 88; Faraday 2000, p. 80

- Faraday 2000, p. 80

- Hughes 2000, p. 89

- Hughes 2000, pp. 89–90

- Knight 2000, p. 88; Faraday 2000, p. 81

- Faraday 2000, pp. 81–82; Hughes 2000, p. 90; Lloyd n.d., p. 15

- Hughes 2000, p. 90

- Lloyd n.d., p. 19

- Hughes 2000, p. 90; Hope 1909, p. 269; Lloyd n.d., p. 19

- Hughes 2000, p. 90; Hope 1909, p. 269; Coppack 2000, p. 145

- Whitehead 2000, p. 113; Coppack 2000, p. 145

- Hughes 2000, pp. 90–91; Whitehead 2000, p. 107; Lloyd n.d., p. 18

- Hughes 2000, pp. 90–91; Whitehead 2000, p. 107; Lloyd n.d., p. 10

- Whitehead 2000, p. 107

- Whitehead 2000, pp. 107–108

- Hughes 2000, p. 91

- Hughes 2000, pp. 91, 93

- Hughes 2000, p. 95; Renn 1987, p. 55

- Hope 1909, p. 258; Hughes 2000, p. 95; Shoesmith 2000c, p. 216

- Hughes 2000, pp. 95–96, 98; Whitehead 2000, p. 115

- Whitehead 2000, pp. 112

- Whitehead 2000, p. 108

- Whitehead 2000, p. 105; Lloyd n.d., p. 17

- Whitehead 2000, pp. 108–111; Lloyd n.d., p. 19

- Hughes 2000, pp. 96–97; Whitehead 2000, p. 112

- Hughes 2000, pp. 96–98; Renn 1987, p. 55

- Lloyd n.d., p. 10; Shoesmith 2000c, p. 216

- Lloyd n.d., p. 10

- Shoesmith 2000c, p. 218

- Whitehead 2000, pp. 114–115

- Clark 1877, p. 165

- Lloyd n.d., p. 18; Stone 2000, p. 212; Hope 1909, p. 263; Whitehead 2000, p. 115

- Hope 1909, p. 257; White 2000, p. 139; Renn 2000, p. 129; Lloyd n.d., p. 21

- Hope 1909, p. 257

- Whitehead 2000, p. 115; Streeten 2000, p. 117

- Whitehead 2000, p. 115

- Lloyd n.d., p. 19; Whitehead 2000, p. 116

- Lloyd n.d., p. 17

- Lloyd n.d., pp. 10–11; Shoesmith 2000c, p. 220

- Lloyd n.d., p. 11; Shoesmith 2000c, p. 222

- Shoesmith 2000c, p. 225

- Shoesmith 2000c, p. 225; Lloyd n.d., p. 18

- Shoesmith 2000c, p. 225; Lloyd n.d., p. 11

- Shoesmith 2000c, p. 226; Lloyd n.d., p. 11

- Streeten 2000, pp. 117, 120

- Streeten 2000, p. 117

- Streeten 2000, pp. 117–118

- Streeten 2000, pp. 119, 122

- Stone 2000, p. 205

- Lloyd n.d., p. 20

- Streeten 2000, p. 122

- Lloyd n.d., p. 17; "Ludlow Festival", Shropshire Tourism, retrieved 26 November 2014; "Ludlow Food and Drink Festival", The Ludlow Website, retrieved 26 November 2014

- "List Entry", English Heritage, archived from the original on 26 January 2014, retrieved 26 November 2014

- "Ludlow Castle", Pastscape, English Heritage, archived from the original on 1 November 2014, retrieved 11 January 2012; "Ludlow Castle", Heritage Gateway, retrieved 12 January 2012

- Shoesmith 2000c, p. 226

- Lloyd n.d., p. 11; Shoesmith 2000c, p. 226; "Historic residence returns to castle". BBC News. 2003. Retrieved 7 November 2014.

- Clark 1877, p. 166

- Hope 1909, p. 258

- Shoesmith 2000a, pp. 15–16

- Renn 2000, p. 135; Shoesmith 2000a, p. 16

- Renn 2000, p. 126; "List Entry", English Heritage, archived from the original on 26 January 2014, retrieved 26 November 2014

- Shoesmith 2000c, pp. 213, 227

- Shoesmith 2000c, p. 213

- Hope 1909, p. 262; Stone 2000, p. 206

- Hope 1909, pp. 261–262; Stone 2000, p. 206

- Stone 2000, p. 208

- Hope 1909, pp. 263–264; Remfry & Halliwell 2000, pp. 202–204

- Remfry & Halliwell 2000, p. 201

- Hope 1909, pp. 263, 265–266

- Hope 1909, p. 266; Curnow & Kenyon 2000, pp. 196, 199–200

- Curnow & Kenyon 2000, p. 198

- Hope 1909, p. 267

- Hope 1909, pp. 259, 267

- Hope 1909, p. 301

- Hope 1909, pp. 268–269, 271

- Fleming 2000, p. 187

- Fleming 2000, pp. 187–180

- Hope 1909, p. 271

- Coppack 2000, p. 145

- Coppack 2000, pp. 147, 149–150

- Coppack 2000, pp. 145–146, 151

- Hope 1909, pp. 271–272; Coppack 2000, p. 145

- Coppack 2000, p. 148

- Hope 1909, pp. 295, 297

- Shoesmith 2000b, p. 175

- Hope 1909, p. 288

- Hope 1909, pp. 288–289

- Thompson 2000, p. 172

- Hope 1909, p. 294

- Hope 1909, pp. 276, 279; Thompson 2000, p. 167

- Hope 1909, pp. 276, 277–279; Thompson 2000, p. 167

- Hope 1909, pp. 277–279; Shoesmith 2000b, pp. 180–181

- Hope 1909, pp. 281–283

- Hope 1909, p. 286

- Morriss 2000, pp. 155, 163–166

- Morriss 2000, pp. 164–166

- Goodall 2011, p. 79

- Hope 1909, pp. 298–299; Renn 2000, p. 127

- Renn 2000, p. 127

- Renn 2000, p. 127; Shoesmith 2000b, p. 180

- Renn 2000, pp. 128–129

- Liddiard 2005, p. 129

- Hope 1909, pp. 299–301

- Hope 1909, p. 306; Renn 2000, p. 133

- Renn 2000, p. 133; White 2000, p. 140

- White 2000, pp. 140

- Renn 2000, p. 138

- Hope 1909, p. 305; Renn 2000, p. 136; Creighton 2012, p. 83

- Renn 2000, p. 130

- Renn 2000, p. 136; Creighton 2012, pp. 82–83; Liddiard 2005, pp. 31–32

- Hope 1909, p. 310

Bibliography

- Clark, G. T. (1877). "Ludlow Castle". Archaeologia Cambrensis. 32: 165–192.

- Cooper, J. P. D. (2014). "Centre and Localities". In Doran, Susan; Jones, Norman (eds.). The Elizabethan World. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. pp. 130–146. ISBN 978-1-317-56579-6.

- Coplestone-Crow, Bruce (2000a). "From Foundation to the Anarchy". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 21–34. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Coplestone-Crow, Bruce (2000b). "The End of the Anarchy to the de Genevilles". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 35–44. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Coppack, Glyn (2000). "The Round Chapel of St. Mary Magdalene". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 145–154. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Creighton, Oliver (2012). Early European Castles: Aristocracy and Authority, AD 800–1200. London, UK: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 978-1-78093-031-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curnow, Peter E.; Kenyon, John R. (2000). "Mortimer's Tower". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 195–200. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Faraday, Michael (2000). "The Council in the Marches of Wales". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 69–82. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Fleming, Anthony (2000). "The Judges' Lodgings". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 185–190. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Goodall, John (2011). The English Castle. New Haven, US, and London, UK: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11058-6.

- Griffiths, Ralph A. (2000). "Ludlow During the Wars of the Roses". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 57–68. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Harding, David (2000). "The Mortimer Lordship". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 45–56. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Hope, W. H. St John (1909). "The Castle of Ludlow". Archaeologia. 61: 257–328. doi:10.1017/s0261340900009504.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hughes, Pat (2000). "The Castle in Decline". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 89–98. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Knight, Jeremy (2000). "The Civil War". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 83–88. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Liddiard, Robert (2005). Castles in Context: Power, Symbolism and Landscape, 1066 to 1500. Macclesfield, UK: Windgather Press. ISBN 0-9545575-2-2.

- Lloyd, David (n.d.). Ludlow Castle: A History and a Guide. Welshpool, UK: WPG. OCLC 669679508.

- Morriss, Richard K. (2000). "The Solar Block". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 155–166. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Pounds, Norman John Greville (1994). The Medieval Castle in England and Wales: A Social and Political History. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-45828-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Remfry, Peter; Halliwell, Peter (2000). "St. Peter's Chapel & the Court House". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 201–204. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Renn, Derek (1987). "'Chastel de Dynan': The First Phases of Ludlow". In Kenyon, John R.; Avent, Richard (eds.). Castles in Wales and the Marches: Essays in Honour of D. J. Cathcart King. Cardiff, UK: University of Wales Press. pp. 55–74. ISBN 0-7083-0948-8.

- Renn, Derek (2000). "The Norman Military Works". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 125–138. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Renn, Derek; Shoesmith, Ron (2000). "The Outer Bailey". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 191–194. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Shoesmith, Ron (2000a). "Ludlow Castle". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 15–20. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Shoesmith, Rob (2000b). "The Tudor Lodgings and User of the North-East Range". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 175–184. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Shoesmith, Rob (2000c). "The Story of Castle House". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 213–228. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Streeten, Anthony D. F. (2000). "Monument Preservation, Management and Display". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 117–122. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Stone, Richard (2000). "The Porter' Lodge, Prison and Stable Block". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 205–212. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Thompson, Michael (2000). "The Great Hall & Great Chamber Block". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 167–174. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- White, Peter (2000). "Changes to the Castle Keep". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 139–144. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

- Whitehead, David (2000). "Symbolism and Assimilation". In Shoesmith, Ron; Johnson, Andy (eds.). Ludlow Castle: Its History & Buildings. Logaston, UK: Logaston Press. pp. 99–117. ISBN 1-873827-51-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ludlow Castle. |