Louis Timothee

Louis Timothee or Lewis Timothy was a prominent Colonial American printer in the Colonies of Pennsylvania and South Carolina, who worked for Benjamin Franklin. He was the first American librarian.[3]

Louis Timothee | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1699 |

| Died | 30 Dec 1738 (age 39) |

| Resting place | Charleston County, South Carolina, USA |

| Occupation | printer |

| Known for | publisher in colonial America |

| Spouse(s) | Elizabeth Villin (maiden name) |

| Children | Peter (b. 24 May 1725) Mary (b. 08 Dec 1726) Louis (b. 19 Jun 1729)[1] Charles (b.14 Sep 1730) [2] Catherine (b. 15 Jan 1735) Louisa (b. 6 Dec 1737) |

| Signature | |

Early life

Timothy was born in Holland to French Huguenot parents who lived in Rotterdam because his parents left France to get away from religious persecution. [4] As a young man in the Netherlands he learned printing from his father.[5]

Timothy, with his wife, Elizabeth, and four sons, moved to British America in 1731. He took the Oath of Allegiance to King George II at Philadelphia upon arrival on 21 September 1731, as was required of all male immigrants to British America.[6][7][8]

Timothy was fluent in German, French, and English as well as his native tongue, Dutch. The month after arriving in Philadelphia, Timothy advertised in the Pennsylvania Gazette his intention to open a "Publick French School; he will also, if required, teach the said language to any young gentlemen or ladies, at their Lodgings."

Timothy advertised for work in Benjamin Franklin's Pennsylvania Gazette initially and got a job as a French teacher.[9] He got acquainted with Franklin in Philadelphia because of his printing skills and started working for him, learning to publish a newspaper.[10] His first attempt at a newspaper was the German-language Philadelphische Zeitung. It came out in the spring of 1732 and failed within a year. After that Timothy was the printer for the Pennsylvania Gazette, owned by Franklin.[1] Franklin was impressed by Timothy's work, so on 26 November 1733 Franklin entered into a six-year contract with him; Franklin would furnish printing equipment for publishing the floundering South Carolina Gazette weekly newspaper in Charleston, South Carolina.[11] Timothy was to publish the newspaper and pay back over six years the expenses Franklin furnished up front.[11] The previous editor, Thomas Whitmarsh, died of yellow fever in 1733; his predecessor died in 1731. Timothy did well as the newspaper publisher and became the official "public printer" and postmaster for the colony of South Carolina. Timothy expanded his printing business to an assortment of jobs, including books and pamphlets. In this period Lewis Timothy's son Peter Timothy was beginning apprenticeship in his father's print shop.[12] The Franklin-Timothy agreement was that Franklin was to provide the printing typefonts and the press.[11] Franklin also agreed to pay one-third of the maintenance costs; in return he was to receive one-third of the profits.[1] The agreement also provided that Peter would have the printing business in the event of his father's untimely death.[13]

Mid life

Timothy's printing career started just following the departure for Carolina of Thomas Whitmarsh, a journeyman in Benjamin Franklin's printing business, whom Franklin funded as a silent partner when Whitmarsh began the South-Carolina Gazette in Charleston.[14] Franklin had an opening for a journeyman in his Philadelphia shop in 1733. Timothy had linguistic abilities and was knowledgeable in the printing trade. Franklin decided to hire Timothy based on these talents since he needed a new printer partner right away. To avoid tipping off his competitors with whom Franklin exchanged other newspapers of Charles Towne printers, Franklin never announced Whitmarsh's death in the Pennsylvania Gazette, but just went ahead and hired Timothy as his replacement.[15]

Franklin hired Timothy by November 1733 on almost the same terms that Whitmarsh had with him as a partner. Timothy probably was already working in Franklin's shop by February 1732. Since Timothy was fluent in German, soon after he was working at Franklin's shop in 1732 Timothy translated into English for publication a lengthy German letter. He had done such a good job at this Franklin shortly afterward assigned Timothy responsibility for a short-lived German-language newspaper.[16]

In 1732 also Franklin arranged for Timothy to serve as a part-time librarian for the Library Company of Philadelphia, one of Franklin's first philanthropic projects. Franklin started the library July 1, 1731. There was no librarian until November 14, 1732,[17] when Timothy was hired as the first salaried librarian in the American colonies.[18] He was paid three pounds sterling every trimester. He worked every Wednesday from two to three o'clock and every Saturday from ten to four.

Later life and death

Timothy arranged with Benjamin Franklin to revive the South Carolina Gazette weekly newspaper. He went to Charleston by himself in the later part of 1733. He started publishing the newspaper on 2 February 1734. Timothy followed later from Philadelphia and went to Charleston in the spring of 1734. She came to Charleston with her six children, four of which were children born in the Netherlands.[7] This was the year Timothy anglicized his name to "Lewis Timothy", being three years after arriving to America.[7][19]

In Franklin's Philadelphia shop Timothy continued Whitmarsh's practice of reprinting essays encouraging people to be optimistic and virtuous. One day in 1738 Timothy informed his readers that his publication of a pamphlet was delayed "by reason of Sicknes, myself and Son having been visited with this Fever, that reigns at present, so that neither of us hath been capable for some time of working much at the Press." Timothy died two months after this announcement. He may have contracted the deadly yellow fever, but there are no records to show this for sure. In fact on January 4, 1739, the South-Carolina Gazette noted that the cause of his death was "an unhappy accident."

Timothy had anticipated the likelihood of his own demise because three previous South Carolina printers had died soon after arriving in the colony. He had put in a special clause inserted in the Franklin partnership contract that his eldest son Peter could succeed him if he prematurely died. Peter was just thirteen years old when Timothy died. He was then training as an apprentice with his father, however was too inexperienced yet to take over the business. Franklin agreed to take on Elizabeth Timothy, the wife of Timothy, as a partner until Peter was capable of running the shop.[20] When Elizabeth became Franklin's printer partner she had six children. Peter took over a portion of the South-Carolina Gazette newspaper publication in 1740 and the complete printing business in 1746 that included the newspaper and printing of government works as the official "public printer" for the colony of South Carolina. When Peter was twenty-one years old he took over the partnership his father had with Franklin and worked closely with Franklin for over the next thirty years.[21]

Works

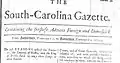

The South Carolina Gazette newspaper of 2 February 1734 is a work attributed to Timothy:

Containg freshest Advices Foreign and Domestick

Containg freshest Advices Foreign and Domestick SC Gazette Feb 2 1734 bottom part of 2nd page

SC Gazette Feb 2 1734 bottom part of 2nd page SC Gazette Feb 2 1734 bottom part of 3rd page

SC Gazette Feb 2 1734 bottom part of 3rd page bottom of fourth page Printed by L. Timothy

bottom of fourth page Printed by L. Timothy

See also

References

- Sherrow 2002, p. 189.

- "Historical Records for: Elisabeth Villin". Family Search. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- Frasca, pp. 73-76

- Krismann 2005, p. 529.

- Frasca 2006, p. 73.

- Baker 1977, p. 281.

- McKerns 1989, p. 700.

- Thomas 1810, p. 155.

- "Elizabeth Timothy". Legacy of Leadership. South Carolina Business Hall of Fame. 1999. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- Schilpp 1983, p. 2.

- Oswald 1965, p. 182.

- Schilpp 1983, p. 3.

- Benjamin Franklin (26 Nov 1733). "Articles of Agreement with Louis Timothée". The Papers of Benjamin Franklin. The American Philosophical Society and Yale University. Retrieved 15 Nov 2013.

- Leonard Woods Labaree, Edmund Sears Morgan, eds. The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, "Biographical Notes", s.v. "Whitmarsh, Thomas".

- Journalism Quarterly, Item notes: v.9 1932, pp. 259-260, Association for Education in Journalism

- Julius Friedrich Sachse, The German Sectarians of Pennsylvania, p. 316, Printed for the author, 1899, Item notes: v. 1

- "Today in History: November 14, 1732". Retrieved 2008-08-27.

- Hudson 2000, p. 41.

- Vaughn 2007, p. 539.

- Benjamin Franklin, Printer By John Clyde Oswald, p. 139, Doubleday, Page & Company, 1917

- McKerns 1989, p. 701.

Bibliography

- Baker, Ira L. (1977). "Elizabeth Timothy - America's First Woman Editor". Journalism Quarterly. Sage Publications. 54 (Spring 1977): 280–285. doi:10.1177/107769907705400207. S2CID 143677057.

- Brigham, Clarence Saunders (1947). History and Bibliography of American Newspapers, 1690-1820. American Antiquarian Society.

- Frasca, Ralph (2006). Benjamin Franklin's Printing Network: Disseminating Virtue in Early America. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-6492-3.

- Hudson, Frederic (2000). American Journalism:a history of newspapers in the United States through 250 years, 1690-1940. ISBN 0-415-22893-X.

- McKerns, Joseph P. (1989). Biographical Dictionary of American Journalism. Greenwood. ISBN 978-0-313-23819-2.

- Krismann, Carol (2005). Encyclopedia of American Women in Business: M-Z Volume 2 of Encyclopedia of American Women in Business: From Colonial Times to the Present. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 031333384X.

- Oswald, John Clyde (1965). Printing in the Americas: ... Kennikat Press.

- Perry, Lee Davis (2009). Remarkable South Carolina Women. Globe Pequot. ISBN 978-0-7627-4343-8.

- Schilpp, Madelon Golden (1983). Great women of the press. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0809310988.

- Sherrow, Victoria (2002). A to Z of American Women Business Leaders and Entrepreneurs. Facts On File, Incorporated. ISBN 978-0-8160-4556-3.

- Thomas, Isaiah (1810). The history of printing in America, with a biography of printers, and an account of newspapers.

- Vaughn, Stephen L. (2007). Encyclopedia of American Journalism. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0203942161.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to a typical eighteenth century colonial print shop. |