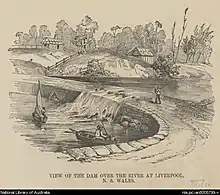

Liverpool Weir

Liverpool Weir is a heritage-listed weir on the Georges River at Heathcote Road near Newbridge Road, Liverpool, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. It was designed by David Lennox and built from 1836 by convict labour, directed by Captain W. H. Christie. It is also known as Bourke's Dam. It was added to the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 13 August 2010.[2]

| Liverpool Weir | |

|---|---|

Location of Liverpool Weir in Sydney | |

| Location | Georges River, Heathcote Road near Newbridge Road, Liverpool, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia |

| Built | 1836[1] |

| Architect | David Lennox |

| Official name | Liverpool Weir Bourke's Dam |

| Type | state heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 13 August 2010 |

| Reference no. | 1804 |

| Type | Weir |

| Category | Utilities – Water |

| Builders | Convict labour, directed by Captain WH Christie |

| |

| Country | Australia |

| Location | Liverpool |

| Coordinates | 33°55′31″S 150°55′42″E |

| Purpose | water supply |

| Status | intact |

History

Some 40,000 years before European settlement of this region of the Georges River, this land was occupied by the Darug people and the neighbouring Tharawal and Gandangara peoples. The land was known as Gunyungalung. The Georges River has been seen by some as the natural (east-west) boundary between the Darug, or "woods" tribe, (north of the river and east to the coast); the "coast" tribes of the Tharawal (south of the river and east to the coast) and the Gandangara (west of the river, inland). Others argue that the region around Liverpool (where the river runs generally west to Botany Bay) signifies an important north–south cultural divide between the Darug peoples living north of the river and the Tharawal to the south of the river. The river demarcated rather than divided groups, providing an "important corridor of mobility" that enabled transport, communication, economic and cultural interaction up, down and across the river on light, rapid bark canoes.[2]

The Georges River area first felt the impact of European settlement in the 1790s when early settlers around the Parramatta area sought out fertile soils for cultivation, moving south along Prospect Creek to the alluvial flats around Liverpool. Facing the steep banks and sandstone cliffs of sections of the Georges River, settlement penetrated slowly in the 1790s.[2]

From the early 1800s the area saw Aboriginal hostilities against settler intrusions with raids on settler crops and stock led first by Pemulwuy of the Bediagal (until his death in 1804, likely at the hands of settlers). Some prominent settlers, who argued that the smaller settlers were the aggressors, themselves sought communication and interaction with Aboriginals, employing them as shepherds and allowing them to remain on the fringes of their landholding. Governor King's 1801 edict, however, prevented settlers harbouring Aboriginal peoples thus effectively excluding Aboriginals from the settled areas. Following the Appin massacre of 1816 the Gandagara and Tharwal kept their distance from the settlers, but they remained around the Georges River.[2]

Governor Macquarie's policy was two-pronged. He authorised settlers around the Georges River to take action against Aboriginal raiders and later instructed the military to make pre-emptive strikes. He also sought conciliation, meeting with the Tharawal when he toured the Cow Pastures in 1810. Kogi of the Tharawal was one who met with Macquarie and who, like other Tharawal, developed close relationships with settlers around the Liverpool area. In 1816 Macquarie issued a call to Aboriginals of the Georges River to lay down arms in return for food, education and secure title to land in the Liverpool area. Kogi was one who took up this option, receiving a King Plate from Macquarie which identified him as "King of the Georges River". Land grants were the only means of effecting land transfer prior to the 1850 legislation that reserved Crown land exclusively "for the use of Aborigines". There are few records of land grants to Aboriginals arising out of the 1816 agreement but there is anecdotal evidence of Aboriginal freehold land along the Georges River until the late 20th century.[2]

In 1810 the Liverpool area was the frontier of settlement, with its alluvial and clay soils increasingly being cleared for farming. Small farming enclaves characterised the area around Liverpool which Governor Macquarie proclaimed on 2 November 1810 as the first of his new towns. The first land grants followed. Partly because of Aboriginal hostilities the area did not take off for settlement, however, until the 1830s.[2]

The construction of Liverpool Weir in 1836 would have impacted on the different Aboriginal groups' use of the river as a communication channel. Construction of the weir would also have gradually changed the ecology of the river upstream.[2]

Liverpool Weir was constructed in 1836 to supply water to local farmers and the town of Liverpool and to serve as a causeway across the George's River.[2]

It was designed by David Lennox, master mason, Superintendent of Bridges for the colony of NSW and Australia's first major bridge builder. Before arriving in Australia in 1832, David Lennox, master mason, had occupied responsible positions in Britain for more than twenty years, working on many bridges including the Menai Suspension Bridge over the Menai Strait and the Over Bridge over the Severn River at Gloucester. Lennox was appointed by Governor Brisbane as Superintendent of Bridges for the colony of New South Wales in 1833. Lennox also undertook many other civil engineering works in NSW from 1832 to 1844, when he was appointed superintendent of bridges for the Port Phillip District in Victoria. For nine years he had charge of all roads, bridges, wharves and ferries and acted as advisor to various government departments. In this period he built 53 bridges. Liverpool Weir is the only weir Lennox is known to have designed in the colony.[2]

Liverpool Weir was one of the two last convict-built public works at Liverpool, the other being Lennox's Lansdowne Bridge over the Prospect Creek on the Hume Highway, Lansvale. On finishing Lapstone Bridge at Mitchells Pass in the Blue Mountains, Lennox took with him the ironed-gang of at least 60 convict workers to start work on Lansdowne Bridge in 1834. These convicts were stationed around Lansdowne Bridge in a township of convicts and the soldiers who guarded them. They were housed in "caravans" that were probably like the portable sleeping boxes used by the road gangs. Married soldiers built themselves tiny slab huts, white-washed and roofed with sheets of bark. Another ironed gang of 50 convicts, together with their military guard, were stationed at a quarry opened by Lennox on the Georges River near Voyager Point (east of present-day Holsworthy). The convict workforce quarried and cut stone and punted it up the Georges River to the bridge site. Lansdowne Bridge was completed and opened by Governor Bourke with great fanfare on 26 January 1836, a testament to the skill of Lennox's design and its convict workforce. The bridge remained closed until September 1836, to allow for construction of the stone tollhouse.[3][2]

Liverpool Weir, also convict-built, was constructed between February and August 1836. In February some of Lennox's convict gangs from the Lansdowne Bridge encampment moved over to the Liverpool Weir site on George's River, below the Liverpool Hospital.[4] Work on Liverpool Weir would have proceeded concurrently with construction of the Landowne Bridge tollhouse. Lennox also used the Voyager's Point quarry for Liverpool Weir with the stone being moved up river on barges.[2]

Captain William Harvie Christie of the 80th Regiment, who had been appointed assistant engineer and Superintendent of Ironed Gangs at Liverpool, oversaw the construction of Liverpool Weir. On Christie's departure from Liverpool in 1839 the populace made him a presentation of a piece of silver plate, expressing their gratitude for the "great improvements which under your direction have been made in the approaches to this town, in the draining of its streets, but more especially...in the completion of that noble work, the Liverpool Dam".[5] Tegg's Almanac of 1842 concurred in this view that Liverpool Weir had boosted the prosperity of the region, noting that it had brought "abundance...to the door of thousands [and that] cultivation is intended and much waste or inaccessible land has been stamped with an intrinsic and permanent value".[6][2]

The weir at the existing site was a compromise between Lennox's initial suggestions of a dam of wooden piles and puddled clay a short distance upstream of the hospital, and a larger masonry structure 11 miles downstream including a road crossing, lock and swivel bridge.[2]

The weir has a curved downstream face and is one of the first "engineered" weirs built in the colony.[2]

Liverpool Weir effectively divided the salt water from the fresh water of the Georges River, allowing the river to be used for irrigated crop growing. But without pumps or reticulation it would seem, in this period at least, water would have been carted to the town of Liverpool. The town had to wait until 1891 for a piped water supply, but it did provide the first cart access to the Moorebank and Holsworthy areas.[7][2]

The weir remained the town's only crossing of the Georges River until the first bridge (a timber truss) was built in 1896 just south of the railway station to connect the town with the rural landholdings. A high level bridge was erected in 1958.[2]

A wharf was constructed at the weir and boats up to 140 tons displacement carried timber and farm produce to Sydney via Botany Bay.[2]

The top was pitched with freestone blocks. Further detail is provided in a letter from the Colonial Architect in 1857, which described the original construction.[8] It noted that the principal wall was ashlar 4 feet (1.2m) thick, built in a circular form with joints radiating to the upstream side. Built on a bed of large blocks of stone "loosely thrown in", 8 feet (2.4m) high in the centre and 11 feet (3.4m) from the bottom of the wall to the base of the river. The 2 feet (0.6m) thick ashlar back wall was constructed 13 feet 6 inches (4.2m) from the centre of the front wall. Three cross walls of unspecified material, but presumably stone, were built to connect the front and back walls at the centre and 20 feet (6.1m) on either side. A statement by Peake[9] was contradicted by the Colonial Architect in 1857 who said that the fill was clay puddle and not ballast and silt. This has been confirmed by later site investigation.[2]

The importance of projects such as this in the early colony cannot be underestimated. The provision of water infrastructure was a problem and a focus for government throughout the 19th century. The construction of a weir in Liverpool happened at the same time as major infrastructure projects in Sydney including the construction of Busby's Bore (Sydney's second water supply, after the Tank Stream) and was immediately followed by the construction of Circular Quay. Liverpool Weir also appears to have been one of the first weirs constructed and still surviving in south and western Sydney.[2]

While bars and riffles are present, it is thought that the river was navigable upsteam of the weir site before the weir was constructed. Governor Macquarie noted in his journal that Liverpool was "admirably calculated for Trade and Navigation ....where the Depth of Water is sufficient to float Vessels of very considerable Burthen".[10] It is also likely that Eber Bunker, sea captain and owner of Collingwood upstream of the weir, sailed his ships to Collingwood to unload. The piers of Bunkers Wharf still survived into the living memory of older (former) residents of Liverpool who were alive at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Navigation would have been curtailed by construction of the weir. However, the pond created by the weir would have permitted the passage of local water craft for some distance upstream.[2]

The river was the most efficient way of transporting goods to and from Liverpool and inland areas so it is likely that the weir would have been used as a transfer point between land and sea-based transportation. Although a wharf had been constructed adjacent to Liverpool Hospital in 1818, a number of industries were located further upstream closer to the weir (including a grain mill and paper mill). It is also possible that the hospital wharf had fallen into disrepair by the 1830s.[11] An 1876 photograph of Liverpool Weir shows a substantial pile of rock directly in front of the weir which would have precluded the weir being used for loading and unloading cargo. However, it also shows a derrick crane on the western side, which supports the theory of the downstream end adjacent the left (west) bank being used for cargo handling purposes.[2]

Colonial Architect correspondence[12] notes the need for repairs as early as 1851. Liverpool Weir was damaged by floods in 1852, by which time the masonry was leaking and the paving between the walls was sinking.[2]

In September 1855 the Colonial Architect reported to the Colonial Secretary that in his opinion the masonry in the circular, lower face of the dam and the straight wall at the back allows water to percolate through; this softens the puddle between the walls which eventually oozes out at the base of the lower wall thus undermining the paving on the top which consequently sinks. He indicated this was the present state of the dam "although it was repaired not more than two or three years ago". He also noted that the piles on the upper side of the dam do not appear to have been closely driven, and in his opinion the injury to the dam arises from its not being water tight.[2]

By 1857 the right (eastern) bank had been washed away. Following a joint report by the departments of the Colonial Architect and Railway in 1957, repair work was carried out in February 1858. It consisted of filling the whole internal portion with puddle clay on which was laid a 9-inch thick bed of concrete covered with stone flagging 12 inches thick, set in mortar and grouted with Portland cement. About 25 feet of the front wall was rebuilt and a wall added at the right end; a row of close piling was driven into the bank at the right bank end of the front wall; and a rubble stone apron of 7260 (square) feet was laid with 2000 (square) feet being required to complete it.[2]

In 1860 another large portion of the eastern (right) bank of the Liverpool Weir was washed away in flooding, cutting a channel around the abutment. As the weir was still being used as the main thoroughfare into Liverpool, it was necessary to extend the weir (and the road on top) across the new channel.[13][2]

For the next 100 years the weir appears to have been left largely untouched. Eventually, decades of flooding caused considerable erosion and the weir needed repairing on several occasions, with a major rebuilding in the 1970s and remediation works in 2007–8.[2]

In the later 1970s part of the front wall that had been washed away was replaced and a precast concrete road was built part way across the top of the weir (this was later removed). Further repair works were carried out in the mid 1980s when the scouring on the eastern (right) bank was addressed reinstating the bank using gabion baskets topped with recovered sandstone blocks. In 1985 surface flagging on the eastern side was replaced following washout of the core, with cast in-situ 1m square concrete units.[2]

A fishway was constructed in 1997 through the heavily modified and extended eastern section of the weir.[14] Damage again occurred in the right bank area in November 2007. Further major remediation works to re-stabilise and prevent erosion to the main wall were carried out in 2007–08.[2]

While originally built to provide water supply and a river crossing for Liverpool, the weir now plays an important role in stabilising the upstream riverbanks and maintaining the hydraulic regime of the upper part of the Georges River estuary. The reaches of river under the influence of the weir have drastically changed since construction in 1836. The construction of a fishway in 1997 provides native fish passage past the weir and improves the ecology of the Upper Georges River, modified by the weir's construction.[15][16][2]

Description

Liverpool Weir is located directly east of Liverpool railway station on the Georges River, approximately 40 km upstream of the river mouth. It spans the full width of the Georges River and forms the river's tidal limit.[2]

Access to the weir is gained via Lighthorse Park on the western (left) bank and the eastern (right) bank of the watercourse. The eastern access point is reached by heading east of Liverpool city centre on the Newbridge Road. On crossing the George's fiver a slip road (the northernmost section of Heathcote Road) branches off immediately to the left (north) and leads directly to the riverbank.[2]

Liverpool Weir was described in 1855 as raising the level of water in the river by 2m, and also providing an access across the Georges River. A nearby former rail bridge was later adapted to provide pedestrian access but was removed in 2007 leaving just the piers. Access across the river is now by the nearby bridge carrying Newbridge Road (2009).[2]

The original 1836 Liverpool Weir was constructed with a curved downstream face of large, dressed sandstone blocks founded on shale bedrock at the left bank and loose large stone on the alluvial sands and clays in the central section. The right bank would have consisted of a sand and gravel bar on the inside of the river bend. However, the original footing arrangement is unknown. Reportedly, the right abutment had been flood damaged some time after completion and was repaired with dressed sandstone blocks supported on round piles (photographed during the inspection of 1979). The 1836 upstream wall consisted of a straight sandstone block wall 13 feet 6 inches (4.11 m) from the centre of the front wall and was likely similarly founded on stone blocks thrown in. Three cross walls connecting the upstream and downstream walls described in the combined Railway and Colonial Architect report of 21 September 1857 were uncovered mostly intact, during the 2008 remediation. These walls contained partly dressed split face blocks that because of their shape and their being inconsistent with the pick finish of the weir blocks, it is likely they were either rejects or leftovers from the recently completed Lansdowne Bridge. The blocks of the internal walls were laid on a 10-20mm lime mortar bed with 5mm shell grit evident.[2]

The upstream and downstream masonry walls along with the internal fill provide the mass to resist the water forces and act as a broad beam across the river. The walls and surface flagging protect the internal clay fill from being damaged and eroded. The internal cross walls, while providing only limited structural function would have allowed staged construction in the dry with diversion of the river flows. The puddle clay rammed between the walls provided the impermeable membrane to create a ponded freshwater storage upstream and prevent the ingress of tidal saltwater. Sandstone flagging approx 2 feet by 3 feet by 12 inches thick served as spillway and provided a wet river crossing and protected the all important puddle clay from flows passing over the weir.[2]

Early in the weir's life, flows passed through the walls and surface flagging causing piping failure of the puddle clay membrane which resulted in settlement of the protective flagging. Once the flagging was dislodged, flood flows further scoured the puddle clay until the walls were directly exposed and collapsed. Extensions as cantilevered walls using sawn timber piles were designed to cut off the flows. These walls were not able to be driven to bedrock nor were they impermeable to the flood waters of the Georges River.[2]

The Colonial Architect, in his 1855 inspection, reported that the means to make the weir impervious to water was to dig out the puddle on both sides of the straight wall and, after pointing or rendering the wall in cement on both sides, to fill in again and well ram the puddle. The term "puddle" is used to refer to working of clay. Typically, a select clay was mixed with sand and an optimum amount of water added to produce a material that was plastic, dense and impermeable when compacted. Compaction was often achieved by driving sheep or other hoofed animals over the surface but, given the convict workforce and the relatively small compartments, it is likely that placement occurred in layers and compaction was achieved through a combination of "treading in" by the convicts and by using timber poles to ram the puddle.[2]

In the combined report of the state of the weir dated 21 September /1857, Joseph Brady of the Railway Department and James Moore of the Colonial Architect's Department ascertained that in 1851 an addition was made to the Dam on the upper side by driving a double row of timber piles about 13 feet (4.0 m) lengths, 13 feet (4.0 m) from the back (stone upstream) wall ... driven into the silt at the back of the dam but they did not reach the bed of the river. The bedrock in the centre of the river here is 14 metres. A roadway of sleepers was then formed between the back (1836) wall and the row of piles. The piles, each about 10 inches (250 mm) by 4 inches (100 mm), increased the height of the weir and also the water storage.[2]

It is unclear from the reports when puddle clay was first placed between the timber piled wall of the roadway extension and the 1836 upstream masonry wall. Both the row of piles and 1836 sandstone back wall were uncovered during the 2008 works including numerous pairs of one metre long wrought iron bars. The bars were anchored into the top of the sandstone wall with lead and with the free end threaded, complete with square nut. It is logical that these bars anchored the 1851 timber sleeper roadway extension to the top of the 1836 upstream wall.[2]

The second extension is believed to have occurred about 1860 and consisted of the driving of a row of timber piles each dressed approximately 12 inches (300 mm) by 2 inches (51 mm) and capped with a crest of sandstone. This addition can be seen in the 1876 photo and further increased the height of the weir. During the period between 1876 and the inspection of 1979 the majority of the sandstone flagging was replaced with concrete flag units. The sandstone crest was also replaced with an exposed aggregate concrete beam.[2]

The 1857 inspection reported the rough stone base had been washed away from the foot of the curved wall causing settlement. A small section of the back wall had also settled with the piling opposite gone to a little extent. The puddle had been washed out from the interior of the old dam for an average depth of 5 feet throughout its whole extent and the flagging had fallen in. The bank at the eastern (right bank) side was washed away to a considerable extent – the floods having formed a passage round that end of the weir. The extensive repairs completed in early 1858 included rebuilding 25 feet of the front wall, adding a wall at the right bank end and piling from the end of the wall to the riverbank. A rubble stone apron was laid to protect against scour and undermining of the walls. The whole of the internal portion was filled with puddle clay with a 9-inch (230 mm) bed of concrete covered with 12 inches (300 mm) thick flagging set in mortar.[2]

From the earliest reports it is evident that scouring had created a deep pool downstream of the weir and had also undercut the downstream right wall. In addition it had removed the right bank, taking out the area where the access road is today. The photo of 1876 clearly shows the scoured right bank and the 1851 roadway addition that reinstated the right bank accessway. The 2008 remediation exposed a row of timber piling retaining each side of the access.[2]

The repairs to address flood damage would also have prompted the authorities, as part of the works, to increase the storage of the weir by raising it and to provide dry access across the river. Increasing the height of the structure also increased the water velocity across the weir, resulting in flood damage to the weir surface, riverbank erosion and undercutting of the downstream wall.[2]

By the time of the 2008 remediation only the curved wall and flagging toward the left bank remained visible of the 1836 weir. Importantly, the stone internal cross walls and the 1836 upstream straight wall remained as important elements.[2]

The puddle clay fill within the weir had been exposed, washed out, and replaced and disturbed by repairs including dwarf concrete cut-off walls. Various services had also been installed over the decades. The report of February 1858 describes repairs executed. These included the whole of the internal portion being filled with puddle clay in which was laid a bed of concrete 9 inches (230 mm) thick covered with stone flagging 12 inches (300 mm) thick. At the time the weir was damaged by the November 2007 flood and remediation works were carried out in 2008, the puddle clay was no longer an original element. The sandstone flagging, with the exception of an area at the left bank, had been lost and replaced with concrete flag units with an exposed 70mm aggregate finish, similar in size to the sandstone units. The piping failure of the clay core and the subsequent sinking and washout of the flag units required installation of a free draining layer of railway ballast wrapped in geotextile. A mass-placed concrete blinding layer 150mm thick with a 200mm thick reinforced concrete integral slab, now provides a protective surface to the original and later 19th century structural elements.[2][17]

Condition

The 2007–08 remediation works revealed that the original masonry upstream wall and three internal cross walls were in good condition.[2]

The Chipping Norton Lake Authority engaged the Government Architects Heritage Group to record the repairs, stabilisation and protection works, to provide advice and to review heritage impact.[2]

The numerous repairs and extensions of timber piled walls within the structure were also in reasonably good condition.[2]

The 1851 timber piled wall roadway extension was generally in reasonable condition but no longer had any evidence of the sleeper roadway other than the wrought iron anchor bars. The upstream timber piled wall of c. 1860 had suffered damage to some areas and was the cause of flow through the structure. This wall is now capped with an exposed aggregate concrete beam. The clay core was suffering a network of piping failure and causing the concrete flag units to settle and dislocate under flood conditions.[2][18]

Although the repair works, extensions, additions and construction of the fishway have had an adverse impact on the integrity of the original 1836 weir and have altered its appearance, much of the form of the original weir still exists within the repaired and extended structure.[2]

Modifications and dates

- 1851: First upstream extension constructed of a timber sleeper roadway, 13 feet (approximately 4 metres) wide. A double row of timber piles and a roadway of sleepers were added between the back (upstream) weir wall and the row of piles.[2]

- 1855: Colonial Architect notes the piles on the upstream side are not closely driven and previous repairs have failed to address seepage and flagging failure.[2]

- 1857: Joint report by the Railway and Colonial Architect Departments identified settlement of walls and flagging and a flood channel scoured through the eastern bank. Specification prepared.[2]

- 1858: More substantial repairs carried out including: 25 ft of the front wall rebuilt and a wall added to at the end; additional close piling to the bank; a 9260 sq ft rubble stone apron constructed to protect against scouring and undermining of walls; whole of the internal portion refilled with clay; new stone flagging in a 9in bed of concrete.[2]

- c. 1860: Further 4 metres upstream extension to the weir consisting of a row of timber piles with stone flagging on the crest. Reportedly carried out to address flood damage and the loss of the right bank.[2]

- 1876: Additions and repairs undertaken to that date are evident in an 1876 photograph showing the crest to be raised substantially above the previous level. By 1876 the crest of the weir was almost 1.5 metres higher than its original 1836 level.[2]

- 1890s: Substantial parts of the sandstone flagged weir surface replaced with exposed aggregate concrete pavers. The upstream sandstone capping beam replaced with exposed aggregate concrete beam. Part of the top course of the curved weir also replaced in a mass concrete in-situ repair with the same exposed aggregate finish.[2]

- 1896: Weir no longer used for water supply (superseded by Liverpool Offtake Reservoir) or as a river crossing (Liverpool Truss Bridge).[2][19]

- 1970s: Part of the front (downstream) weir wall washed away and replaced. A concrete road was built part way across the top of the weir (later removed).[2]

- 1980s: Major repairs by the Chipping Norton Lake Authority included: removal of the 1970s concrete road; underpinning the curved downstream sandstone wall with concrete and filling of the large scour hole in the right (eastern) bank. The filled area was retained with a wall of rock-filled wire (gabion) baskets to the downstream edge with geotextile and large rock armouring to the surface. The retaining wall was finished with a capping of sandstone blocks retrieved from the riverbed downstream. The riverbed downstream was protected from further scour by the placement of rock-filled wire mattresses.[2]

- 1985: Sandstone surface flagging on the eastern bank re-laid with some replaced with concrete units.[2]

- 1995: Geotechnical Engineering Group commissioned by the Chipping Norton Lake Authority to carry out an investigation for a proposed 60m long, variably 2-3m deep and several metres wide, fish way at the weir to reinstate native fish passage to the upper reaches of the Georges River.[2]

- 1997: Fishway completed, through the heavily modified and extended eastern section of the weir.[2]

- 2006: Weir noted to be in poor repair with leakage in the masonry causing water to run through (rather than over) the structure, resulting in wear and collapse. Remediation works were considered necessary to ensure the long term survival of the structure. Heritage Impact Assessment prepared by Government Architect's Office, Department of Commerce, May 2006. The Heritage Office provided comment in 2007, supporting the proposed works.[2]

- 2007: Partial collapse of the weir following a storm.[2]

- 2007–08: Chipping Norton Lake Authority implemented emergency repairs to safeguard the weir from further flood damage, permitting remediation work on the fragile structure to protect the weir's heritage fabric. The design allowed management of minor floods, provided temporary access and a platform for large construction plant, and protection from abrasion and vibration. The work included installation of a composite steel and concrete sheet pile wall vibrated 10 metres into the river sediments. The sheetpile wall incorporated stainless steel permanent formwork and special concrete mix capping beam. Protection of the original internal weir elements involved provision of internal drainage layers and an integral reinforced concrete slab surface to replace the trouble-fraught flagging. The old concrete flag units were used as scour protection of the upstream and downstream walls.[2]

Heritage listing

Liverpool Weir is state significant for its historical, historical association and rarity values. It is the only weir in NSW known to have been designed by master mason David Lennox. Before arriving in Australia in 1832, Lennox had occupied responsible positions in Britain for more than twenty years, working on many bridges including Telford's great suspension bridge over the Menai Straits and the stone-arch bridge over the Severn River at Gloucester. Lennox was Australia's first major bridge builder and is a significant figure in NSW's history. He was responsible for many bridges and other civil engineering works in NSW between 1832 and 1844, when he was appointed superintendent of bridges for the Port Phillip District in Victoria. For nine years he had charge of all roads, bridges, wharves and ferries and acted as advisor to various government departments. In this period he built fifty-three bridges.[2]

Liverpool Weir was one of the first "engineered" weirs built in the colony.[2]

Built in 1836, it is one of the earliest surviving stone weirs constructed in Australia and one of the few surviving weirs constructed in the early colonial era for the supply of water to a township.[2]

Liverpool Weir is an example of the construction of the colony's infrastructure by convict labour, in particular by convicts undergoing secondary punishment. It demonstrates the harsher punishment regime in NSW decreed by the British Government from the mid 1820s to the 1840s in order to revive the fear and dread of transportation. Under this system, re-offending convicts were put to work in gangs on constructing roads, bridges, other public works, timber-getting and lime-burning. Some convicts, including some of those in the Liverpool district, were sentenced to work in irons.[2]

Construction of the weir within the flowing and flood-prone Georges River was an achievement. It has survived despite damage from the first floods and others since, which necessitated repairs, stabilisation and extensions.[2]

Investigations in 1979 and repair work in 2007–08 have revealed much about the weir's original construction, the techniques adopted during repairs and extensions in the 1850s and the nature of subsequent extensions and repair works. Short of major intervention work, it is unlikely that further structural research and inspection will reveal more about the weir's construction.[2]

Apart from extensions, a concrete road was partly built across the weir in the 1970s which was halted and later removed because of its impact on the weir's stability, and a fishway was built in 1997 through the right abutment.[2]

Although the repair works, extensions and additions have had an adverse impact on the integrity of the original structure and have altered its appearance, Liverpool Weir is a rare 19th century water supply structure, and its original and repair fabric have historic and heritage significance.[2]

While the weir has long ceased to function as a source for town water and as a George's River crossing, it has gradually developed other functions. It now provides water-based recreational opportunities. It has facilitated re-establishment of the natural migration of fish upstream with construction of the by-pass fishway in 1997. It maintains the (modified) stable condition of the upper Georges River (except for re-admitting fish migration) and it is now a control structure that restricts river bed lowering and bank erosion.[2]

Liverpool Weir has local significance for its potential for research into changes in ecology from below to above the weir, during the 170 years of its existence.[2]

Liverpool Weir was listed on the New South Wales State Heritage Register on 13 August 2010 having satisfied the following criteria.[2]

The place is important in demonstrating the course, or pattern, of cultural or natural history in New South Wales.

Constructed in 1836 Liverpool Weir has state significance as one of the earliest surviving stone weirs built in Australia and one of the first "engineered" weirs built in the convict colony.[2]

The weir is a rare surviving example of early colonial engineering and demonstrates some of the difficulties overcome in designing water related infrastructure at this time. Relatively few engineering works of this nature survive from the early colonial period of NSW's settlement.[2]

Colonial engineering works, particularly those in a setting that can evoke a sense of the colonial landscape (as demonstrated in the downstream view from Liverpool Weir) are relatively uncommon in NSW. Surviving examples provide a tangible link and experience that can not be replicated by photographs or written records.[20][2]

As a surviving structure built by convict labour, Liverpool Weir has historical significance at state level for its capacity to demonstrate the convict system in NSW in the 1830s. The weir is evidence of the convict-built colonial infrastructure constructed under the harsher system of secondary punishment for repeat offenders that was introduced into the colony from the mid 1820s. Under this system many convict gangs (like the Liverpool Weir convicts) worked in irons.[2]

Liverpool Weir has state significance for its long continuity of use. While it ceased use as a fresh water supply and as a river crossing in the 1880s and as a river crossing in the 1890s, it has since gradually developed other functions. It now provides water-based recreational opportunities. It has facilitated re-establishment of the natural migration of fish upstream with construction of the by-pass fishway in 1997. It maintains the (modified) ecology of the upper Georges River (except for re-admitting fish migration), and it is now a control structure that restricts river bed lowering and bank erosion, caused by 20th century sand extraction downstream.[2]

The construction of Liverpool Weir is historically significant for its impacts on the traditional way of life of the Darug, Tharawal and Gandangara peoples whose lands bordered the Georges River and whose interactions were governed by free movement up and down the river in bark canoes. The weir created a barrier to this long-standing channel of communication between the Aboriginal peoples of the Georges River. By providing a fresh water supply to the settlers of the area and to the town of Liverpool, as well as access across the Georges River, the weir fostered settlement of the area and consequent Aboriginal dispossession.[2]

The weir's construction had environmental impacts on the ecology of the river upstream, creating a tidal barrier between the saline and fresh waters of the Georges River.[2]

Liverpool Weir has local significance as the source of the first reliable public water supply for the town of Liverpool, from 1836 until c. 1880; as the only crossing of the Georges River at the town until the first bridge was built in 1894 and as the focus of a river port for Liverpool. A wharf was constructed below the weir and ships were loaded to carry timber and farm produce to Sydney via Botany Bay.[2]

The place has a strong or special association with a person, or group of persons, of importance of cultural or natural history of New South Wales's history.

Liverpool Weir has state significance for its strong association with its designer, David Lennox; with the convicts under sentence who laboured in ironed gangs to build it, and with Captain William Christie who supervised the convict workforce.[2]

Before arriving in Australia in 1832, David Lennox, master mason, had occupied responsible positions in Britain for more than twenty years, working on many bridges including Telford's great suspension bridge over the Menai Straits and the stone-arch bridge over the Severn River at Gloucester. Lennox was appointed by Governor Brisbane as Superintendent of Bridges for the colony of NSW in 1833. Lennox was Australia's first major bridge builder but he also undertook many other civil engineering works in NSW from 1832 to 1844, when he was appointed superintendent of bridges for the Port Phillip District in Victoria. For nine years he had charge of all roads, bridges, wharves and ferries and acted as advisor to various government departments. In this period he built 53 bridges. A number of his works in NSW, namely the Lansdowne Bridge over the Prospect Creek on the Hume Highway at Lansvale; the Lennox Bridge at Parramatta and the Lapstone Bridge at Mitchell's Pass in the Blue Mountains are still standing and are listed on the State Heritage Register.[2]

Captain William Harvie Christie of the 80th regiment was assistant engineer and Superintendent of Ironed Gangs at Liverpool whose work in completing Liverpool Weir was particularly noted by the grateful local community and his contemporaries.[2]

The convict workforce was likely the same ironed gang who worked first on Lennox's Lapstone Bridge (in the Blue Mountains), then his Lansdowne Bridge over the Prospect Creek at Lansvale on the Hume Highway, before moving on to the Liverpool Weir.[2]

The place is important in demonstrating aesthetic characteristics and/or a high degree of creative or technical achievement in New South Wales.

Liverpool Weir is not state significant under this criterion.[2]

The place has a strong or special association with a particular community or cultural group in New South Wales for social, cultural or spiritual reasons.

Liverpool Weir is not state significant under this criterion.[2]

The place has potential to yield information that will contribute to an understanding of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Liverpool Weir is not state significant under this criterion.[2]

Investigations in 1979 and repair work in 2007–08 revealed much about the weir's original construction and the nature of subsequent extensions and repair works. Short of major intervention work, it is unlikely that further structural research and inspection will reveal more about the weir's construction.[2]

Liverpool Weir has local significance for its research potential into changes in ecology from below to above the weir, during 170 years of existence.[2]

The place possesses uncommon, rare or endangered aspects of the cultural or natural history of New South Wales.

Liverpool Weir is state significant as it is the only weir designed by David Lennox, master mason, Superintendent of Bridges for the colony of NSW (1833–44) and Australia's first major bridge builder. Lennox is known primarily for his bridges. Liverpool Weir is the only surviving example of Lennox's "non-bridge" work.[2]

Liverpool Weir is one of the earliest surviving stone weirs built in Australia, one of the first "engineered" weirs built in the convict colony on NSW, and one of the few surviving weirs constructed in the colonial era for the supply of water to townships.[2]

The place is important in demonstrating the principal characteristics of a class of cultural or natural places/environments in New South Wales.

Liverpool Weir is state significant as an example of an early low-level colonial weir of the convict era.[2]

See also

References

- "ADVANCE AUSTRALIA Sydney Gazette". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. New South Wales, Australia. 26 January 1836. p. 2. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- "Liverpool Weir". New South Wales State Heritage Register. Office of Environment and Heritage. H01804. Retrieved 2 June 2018.

- (Keating, 1996, 63; ADB, Liston, 2009, 18; )

- Keating, 1996, 64

- ADB, 1969, pp. 393-4; Keating, 1996, 64

- (quoted in Keating, 1996, 64)

- Keating, 1996, 64, 90

- AONSW 2/600 dated 21/9/1857

- (quoted in Laurie, Montgomery & Petit, 1980, 3)

- "GOVERNMENT AND GENERAL ORDERS". The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. New South Wales, Australia. 15 December 1810. p. 1.

- Corroneos, 1996, 8

- AONSW 2/600

- Keating, 1996, 82; NSW Govt Arch Office, 1996, 10-11

- NSW Govt Arch Office, Liverpool Weir Remediation, September 2009

- (Chipping Norton Lake Authority Annual Report 2008–09)

- Sources: Renwick, 2010 pers. comm.; Clarke, 2010 pers. comm.; Chipping Norton, 2009; NSW Govt Arch Office, 2006, 2009; DNR, 2006; Liverpool LEP, 1994; Keating, 1996, Corroneos, 1996; ADB, 1969; AONSW 2/600; Cole, 2000; Laurie, Montgomery & Petit, 1980

- (Sources: EHC, 2008; Chipping Norton, 2009: DNR, 2006; NSW Govt Arch Office, 2006 & 2009; LEP 1994; AONSW 2/600 NSW; Renwick, 2010; Clarke, 2010: pers. comm)

- (DPWS May 1999, Heritage Impact Assessment 2006, DNR 2006, Appendix D)

- "OPENING OF THE LIVERPOOL BRIDGE". The Daily Telegraph. Sydney. 3 April 1894. p. 6.

- Government Architect's Office, 2006, 17

Bibliography

- Chipping Norton Lake Authority Annual Report. 2009.

- Chipping Norton Lake Authority Annual Report. 1999.

- Liverpool Dam: Liverpool Local Environmental Plan. 1994.

- AONSW 2/600 NSW.

- Associate Professor (Dr) Carol Liston, University of Western Sydney (2009). Personal communication.

- B Cole (ed) (2000). Dam Technology in Australia 1850–1999.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Coroneos, C (1996). Maritime Archaeological Assessment of Liverpool Weir Fishway.

- Keating, C (1996). A Social History of Liverpool.

- Liston, Carol (2009). Pictorial History: Liverpool & District.

- Casey & Lowe Associates (1999). Heritage Assessment: Liverpool Weir and Proposed Fishway.

- Haworth, David (1969). Christie, William Harvie (1808–1873).

- Department of Natural Resources (DNR) (2006). Statement of Environmental Effects for Liverpool Weir Remediation Works.

- FORM Architects Australia (2004). Heritage Study Review.

- Goodall, H & Cadzow, A (2009). Rivers and Resilience: Aboriginal People on Sydney's Georges River.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Government Architect's Office Heritage Group (2009). Liverpool Weir Remediation, Summary of 2007–08, Repairs, Stabilisation & Protection Works: Review of Heritage Impact, Report No 09067.

- Government Architect's Office, Department of Commerce (2007). Liverpool Weir.

- Heritage Group, NSW Government Architects Office (2007). Liverpool Weir Following Partial Collapse.

- J Maddocks, Senior Engineer, Brewsher Consulting (2001). Have We Forgotten About Flooding on the Georges River?.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- JM Antill, Consulting Engineer (1967). Lennox, David (1788–1873).

- Laurie, Montgomerie & Petit (1980). Restoration of Liverpool Weir.

- Manly Hydraulics Laboratory (1980). Liverpool Weir – Model Study of Mattress Protection.

- Michael Clarke, Engineering Heritage Committee, Engineers Australia (2010). Personal communication.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- National Trust of Australia (NSW) (1986). National Trust Suburban Register.

- Neustein & Assoc (1992). Liverpool Heritage Study.

- NSW Government Architect's Office (2006). Liverpool Weir Heritage Impact Assessment.

- Sutton, R (1984). George Barney RE (1792–1862), First Colonial Engineer, Paper, Engineering Conference, 2-6 April 1984, Brisbane.

- Renwick, Scott (2009). Submission by the Chipping Norton Lake Authority for Liverpool Weir Remediation Project No. M10.

- Scott Renwick, former Project Manager Chipping Norton Lake Authority & Liverpool Weir Remediation Project (2010). Personal communication.

- Andrews, V A (2010). Submission.

Attribution

![]() This Wikipedia article was originally based on Liverpool Weir, entry number 01804 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.

This Wikipedia article was originally based on Liverpool Weir, entry number 01804 in the New South Wales State Heritage Register published by the State of New South Wales and Office of Environment and Heritage 2018 under CC-BY 4.0 licence, accessed on 2 June 2018.