Lindholm amulet

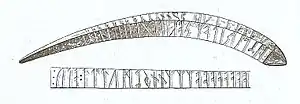

The Lindholm "amulet", listed as DR 261 in Rundata, is a bone piece, carved into the shape of a rib, dated to the 2nd to 4th centuries (the late Roman Iron Age) and has a runic inscription. The Lindholm bone piece is dated between 375CE to 570CE and it is around 17 centimeters long at its longest points. It currently resides at Lund University Historical Museum in Sweden.[1]

It was found in 1840 in Skåne, Sweden, while cutting peat from a bog.[2] This cut the bone in half and resulted in the destruction of one rune in the second line of text though most of the artifact remained intact.[2]

These runic objects were offered to the water in the bogs, the same is probably true in other regions in lakes and streams, but these objects are more difficult to retrieve. Bogs provide near perfect preservation for these types of artifacts thanks to the static, murky waters allowing them to rest undisturbed and unreachable for thousands of years.

Inscription

The inscription reads

- ᛖᚲᛖᚱᛁᛚᚨᛉᛋᚨ[ᚹ]ᛁᛚᚨᚷᚨᛉᚺᚨᛏᛖᚲᚨ᛬

- ᚨᚨᚨᚨᚨᚨᚨᚨᛉᛉᛉᚾᚾ[ᚾ]ᛒᛗᚢᛏᛏᛏ᛬ᚨᛚᚢ᛬

- ekerilazsa[w]ilagazhateka:

- aaaaaaaazzznn[n]bmuttt:alu:[3]

The first line is transcribed into Proto-Norse as either Ek erilaz sa Wilagaz haite'ka or Ek erilaz Sawilagaz haite'ka. This translates to "I am (an) erilaz, I am called the wily" (or "I am called Sawilagaz"). If the word in first line is translated as a name, Sawilagaz means "the one of the Sun (Sowilo)". If the word is translated as "the wily" or "crafty one" or "deceitful one", then it may be related to a byname of Odin or another god.[2]

The sequence in the second line contains a "magical" string of runes concluding in alu. The three consecutive Tiwaz runes as an invocation of the god Tiwaz, and the eight Ansuz runes as an invocation or symbolic list of eight gods.[4]

Interpretation

It is partially due to the formula of the inscription itself which references the way Odin often used to characterize himself as Grimnismal. The word 'erilaR' is frequently found in runic writing as a way to self identify the person carving the rune. The inscription may also be interpreted as “I ‘the eril’ the one who knows magic”. The reason for the rune inscriber to describe himself as crafty or tricky is most likely because he is about to enter a situation in which he will be in need of these qualities in order to be victorious. This gives us some insight into the purpose of the Lindholm amulet and other such historic rune artifacts.[5]

The interpretation of the Lindholm amulet is very loose, scholars and archaeologists alike have tried their best to decipher its strange inscriptions but it is likely that the writer either had less logical uses for the inscriptions than conveying a clear message or was not completely literate in the runic alphabet as was often the case with anyone who was not a spiritual leader or a person of great power.

Alphabet

The writing is of the specific runic alphabet is known as Elder Futhark[6] and is the oldest form of runic writing and was often used by both germanic and northwest germanic tribes to inscribe weapons, amulets and instruments of magic. Elder Futhark was for example used for the Proto-Norse language.[1]

Runic writing was ideal for inscribing into wood or bone because it was composed primarily of vertical and diagonal lines, always going against the grain. The word rune itself means to carve or cut into. Because of the simplicity of the runic alphabet it is less likely that the amulet itself underwent any sort of erosion capable of obscuring or otherwise making the inscriptions illegible during its time in the bog or during its unearthing.

The runic alphabet on the surface is nothing more than a simple code for communication and recording. It is very difficult to know for sure the intended purpose of these runic inscriptions; many believe they have religious, spiritual or even magical connotations. Many believe the runic alphabets sole purpose to be for magical uses. The Lindholm bone piece has a seemingly meaningless inscription carved into its surface and for this reason it is often considered to be a prime example of rune magic used perhaps to assist a warrior in battle or even to help bring prosperity to a poor beggar.[7]

It is very probable that this specific artifact was an amulet used for magic purposes, to summon the power of some deity. This is shown by the inscription itself, instead of reading logically, it repeats, a row of *ansuR could be read as a repetition of calling on a deity eight times as one would do in a magical ritual. That being said, it is important to keep in mind that the runic alphabet was used for many things outside of magical incantations and ritualistic devices.[4]

Similarity to the Kragehul spear shaft

The Kragehul spear shaft (which was also found in a bog) and the Lindholm amulet are said to have extremely similar inscriptions. This may be due to the fact that it is fairly common in rune writing to follow the formula of “I so-and-so” when engraving an object with runic inscriptions.[8]

See also

References

- "Lindholmen, bone piece". RuneS database. Academy of Sciences Göttingen.

- Flowers, Stephen E. (2006), "How to do Things with Runes: A Semiotic Approach to Operative Communication", in Stoklund, Marie; Nielsen, Michael Lerche; et al. (eds.), Runes and Their Secrets: Studies in Runology, Volume 2000, Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press, pp. 72–79, ISBN 87-635-0428-6

- Project Samnordisk Runtextdatabas Svensk – Rundata.

- Spurkland, Terje (2005). Norwegian Runes and Runic Inscriptions. Boydell Press. p. 12. ISBN 1-84383-186-4.

- Stoklund, Marie (2006). Runes and Their Secrets: Studies in Runology. Museum Tusculanum Press. pp. 72–73, 461. ISBN 9788763504287.

- Kodratoff, Yves. "Nordic Magic Healing: runes, charms, incantations, and galdr". www.nordic-life.org. Retrieved 2019-05-06.

- Looijenga, Tineke (2003). Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions. Brill Press. pp. 12, 383. ISBN 9004123962.

- Looijenga, Tineke (2003). Texts and Contexts of the Oldest Runic Inscriptions. Brill Press. pp. 135, 383. ISBN 9004123962.